American Trans Air - the next US Major

July 1999

After overextending itself with scheduled service expansion and turning loss–making three years ago, American Trans Air (ATA), the largest charter carrier in the US, recovered quickly and is now reporting record profits. It is on the verge of attaining “Major” carrier status with $1bn–plus revenues this year. How will ATA balance the opportunities available in the scheduled, commercial charter and military sectors to consolidate profitability?

ATA is a rare survivor among the older–established US carriers trying to make a living in the charter business. Founded in 1973 by its present chairman J. George Mikelsons, the Indianapolis–based carrier initially provided air services for Ambassadair travel club, utilising 720s and later 707s. In 1981, following deregulation, ATA was certified as a common air carrier and began providing capacity for tour operators.

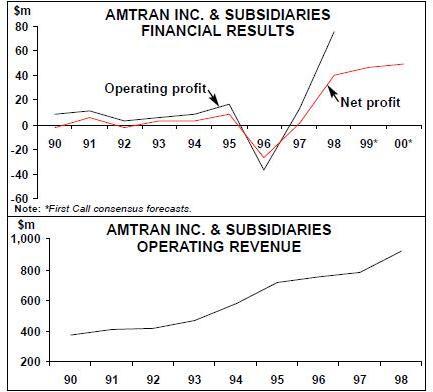

The company grew rapidly in the 1980s, establishing itself as the nation’s largest passenger charter operator, venturing into scheduled services and building up a sizeable military charter business. The annual operating revenues of Amtran Inc, a holding company formed in 1984, almost doubled to $422m between 1988 and 1992.

In early 1993 Mikelsons took Amtran public, raising $37.3m in an IPO that reduced his ownership to 75%, gave employees a stake, attracted many institutions and listed the company on NASDAQ. The debut was not well–timed as, during a general downturn of industry stocks, Amtran’s share price plummeted from the $16 offer price to a low of $6 in 1994, but since then the stock has been a decent performer.

After an unbroken profit record through the 1980s, Amtran reported marginal $2m net losses in both 1990 and 1992. But, rather exceptionally among the large US carriers, it reported a $5.6m net profit for 1991. Its ability to weather the recession so well was in large part due to the military business generated by the Gulf war.

But in 1996 ATA succumbed to the ills affecting the US low–cost airline sector generally — increased price competition from the major carriers or their low–cost subsidiaries in the East and higher fuel prices, followed by a sharp reduction in demand in the wake of the ValuJet crash and grounding. The situation was aggravated by rapid growth — ATA was adding capacity at a year–over–year rate of 30% just as demand collapsed. As a result, Amtran reported $36m and $27m operating and net losses respectively for 1996.

The company was able to recover because of its quick response to the crisis. In August 1996 Mikelsons ceded the role of CEO to Stanley Pace, a management consultant who had worked on Continental’s successful turnaround. Pace implemented a modest downsizing, which included pulling out of many scheduled markets, disposing of seven 757s, cutting the workforce by 15% and improving on–time performance and customer service.

Although Stanley Pace stepped down after only nine months on the job (the current CEO/president is John P. Tague, with Mikelsons retaining the role of chairman), the good work had been done. Amtran turned itself around in 1997, reporting an operating profit of $13.5m and marginal net earnings of $1.5m.

Amtran celebrated its silver anniversary year with record operating and net profits of $75.4m and $40.1m respectively, on revenues of $919m, in 1998. For the first time, its profit margins (8.2% and 4.4%) were getting close to the lower end of the range reported by the major carriers.

The first quarter of this year saw record earnings for the fifth consecutive reporting period: a $16.5m net profit, representing 5.9% of revenues. This prompted Amtran’s board to authorise the repurchase of 600,000 shares to enhance shareholder value, following an earlier programme covering 250,000 shares.

All of this has been reflected in Amtran’s share price, which began to rise rapidly in early 1998. The price neared the $30–mark in July 1998 but then declined in line with the airline industry trend. This year has again seen steady improvement, to about $24 in late June.

Amtran’s stock performance has, of course, been helped by Wall Street’s sudden interest in the company. It is hard to understand why analysts took so long to start covering the nation’s 11th largest and fairly consistently profitable carrier. This may have been because of the old–fashioned and risky image of an operator that relies on the charter segment and may not have the right product to succeed in the scheduled business.

But the record first–quarter 1998 profits changed all that. Companies like Salomon Smith Barney and Morgan Stanley Dean Witter initiated coverage of Amtran early last year, with ratings such as “buy” and “outperform”. SSB considered that the carrier was “finally ready to show positive earnings momentum”. The four brokers reporting on Amtran to First Call still rate it as a “buy” and predict that earnings will rise by 11% to $3.41 per diluted share in 1999 and by another 6% in 2000.

Diversified revenue base, low cost structure

Like Tower Air and other US charter operators, ATA enjoys much flexibility in that it is able to switch capacity between commercial and military charters — and to some extent between charter and scheduled operations — as market conditions dictate. Charters can be used to test new markets before scheduled service is introduced. Currently 52% of Amtran’s revenues come from scheduled services, while commercial and military charters account for about 26% and 12% respectively.

Unlike the new crop of low–cost carriers such as AirTran and Frontier, which have gone upmarket with separate business class products in an effort to improve their image in the post–ValuJet era, ATA has retained a very clear identity as a carrier focusing on the leisure segment. This is because of its determination to keep costs low. Its reputation as an old–established operator with a perfect safety record obviously helps. Like Southwest, ATA has always performed its own maintenance — at facilities at its main hubs in Indianapolis and Chicago–Midway — and even operates a centre training maintenance technicians.

The aim has always been to provide leisure travellers what they need: low–cost and convenient air service with few restrictions. However, recent expansion into higher yield markets has prompted the carrier to start evaluating product enhancements, such as separate check–in and preferred seating for business travellers, that would not add substantially to costs.

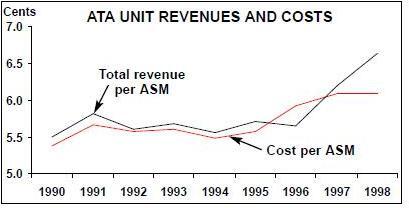

Extremely low unit costs are a major advantage, which ATA has managed to retain despite scheduled expansion and rapid growth generally. In 1998 its operating costs per ASM, at 6.1 cents, were the lowest among the large US carriers. The rather alarming 9.3% surge in unit costs in the March 1999 quarter was attributed to the inclusion of two newly–acquired tour operators that do the bulk of their business in the winter period.

ATA also benefits from excellent labour relations. In late 1996 it secured a favourable four–year contract with its pilots and flight engineers. Although current negotiations with the flight attendants — whose contract became amendable at the end of last year — are proving tough, there is no sign of any labour unrest.

The past year has seen substantial improvements on the revenue side thanks to a better pricing environment and efforts to reduce seasonality. In 1998, when unit costs remained flat (attributed to an improved budgeting process as crew training and labour costs rose sharply), scheduled service yield and unit revenues surged by 7.4% and 9.9% respectively. A new revenue management system is expected to improve scheduled service unit revenues by 2–3% next year.

The Amtran empire

Another factor that differentiates Amtran from the 1990s low–cost new entrants is that a whole host of support companies have been gathered under the holding company umbrella. The older–established subsidiaries include ATA Vacations, ATA Training, ATA Air Freight (cargo sales and marketing) and American Trans Air ExecuJet (business aviation). Recent months have seen the addition of Chicago Express (feeder carrier), Amber Air Freight and two Detroit tour operators — all were existing partners and some were already partially owned by Amtran.

The Amber Air Freight transaction involved Amtran increasing its stake from 50% to 100% in the company that markets its bellyhold cargo and mail capacity. Amber has been very successful, experiencing strong profit growth in recent years, and is expected to earn $13m revenues and contribute $6m in pre–tax profits this year.

In late May Amtran completed the acquisition of Chicago Express, which has been its feeder partner at Chicago–Midway since 1996. The commuter carrier operates Jetstream 31s, linking ATA’s hub with points such as Grand Rapids and Lansing in Michigan, Des Moines in Iowa, Dayton in Ohio and Madison in Wisconsin. The plan is to grow the business with service to more secondary cities, and utilising larger aircraft is currently under consideration.

Charter versus scheduled

After the initial Indianapolis–Ft. Myers flights in 1986, ATA began to expand its scheduled service rapidly in the early 1990s. Between 1990 and 1995, that segment grew from just 7% to about 50% of Amtran’s total revenues, as a substantial network was built from the Indianapolis and Chicago–Midway hubs, as well as from Milwaukee and Boston, to Florida, the Caribbean, the West Coast and Hawaii.

However, the new services yielded disappointing results. The rapid pace of expansion caused unit costs to soar and aggravated competitors, while the product on offer was not up to scratch. The ValuJet effect was the last straw, and in late 1996 ATA pulled out of many scheduled markets in favour of refocusing on the core charter business. This involved eliminating all scheduled service from Boston (to various Florida cities) and on five other routes to Florida and the Caribbean.

The carrier retained profitable scheduled routes, all of which then originated from its two Midwest hubs. This was generally regarded as a smart move as Indianapolis and Chicago–Midway are important leisure and business markets but do not capture the attention of the major carriers like Boston does. Serving common destinations from those cities also allows operating synergies. Consequently, scheduled expansion resumed almost immediately.

Over the past two years the strategy has been, first, to continue to build leisure–oriented operations from the Midwest. ATA has substantially increased service to the West Coast and Florida, returned to Jamaica on a seasonal basis and added Mexico and Puerto Rico to the network.

Second, the carrier has ventured into key business markets such as New York (JFK and LaGuardia), Dallas (DFW), Denver and Philadelphia. This is a new strategy but not really that risky as ATA is not stepping on the major carriers’ toes by operating out of Midway. The three–per–day Midway- Philadelphia service that began in May provides the only non–stop connection in that market.

Third, after testing the transatlantic market with charters for three years, this summer ATA has launched seasonal scheduled service from JFK to Shannon, Dublin and Belfast, with same–aircraft originating service from Midway and Los Angeles. In another move to utilise new hubs outside the Midwest as opportunities arise, San Juan has been linked with separate services from JFK and Ft. Lauderdale.

Thanks to scheduled expansion, last year ATA was able to report a profit in the fourth quarter for only the second time in the company’s history. Expansion in that sector will therefore continue and scheduled revenues are expected to reach $600m this year. However, ATA will not follow the example of Sun Country, the nation’s second largest charter carrier, which totally revised its strategy by becoming a scheduled operator in June (it is now challenging Northwest in its key markets out of Minneapolis). ATA’s commercial charter division, which is run fairly separately from the scheduled division, will continue to grow as well.

Like Tower Air, the nation’s third largest charter operator, ATA anticipates strong growth in military charter revenues. It has long been the largest civilian provider of passenger airlift for the US military — a role that has made it less sensitive to the vagaries of the economic cycle. The Yugoslav conflict has provided a major boost to ATA’s military revenues, which are expected to double to $125m this year. Citing an overall strategy of “significantly improving our presence in the military market”, which will be facilitated by the addition of longer–range L–1011–500s, Amtran expects its military revenues to grow by 60% to $200m next year.

Fleet and financing plans

ATA’s current 49–strong fleet consists of 24 727–200s, nine 757–200s and 16 L–1011s. The 727–200s were added in 1993 as 727- 100 replacements, and there are currently no plans to replace the bulk of that fleet.

The 757 was introduced in 1989, when an opportunity came to acquire good–quality aircraft from SIA, and the type is used primarily in scheduled service. Two additional 757- 200s are due to join the fleet this autumn and a third, which is expected to replace an existing 727–200, in June next year. This will give ATA a fleet of 11 757s.

The main charter workhorse in ATA’s fleet is the Lockheed L–1011, which has been utilised since 1985. Earlier this year the carrier introduced to service the first two of five longer–range L–1011–500s acquired from Royal Jordanian last year. The third aircraft is expected this month (July) and the fourth and fifth by year–end.

The L–1011–500s are a welcome addition to the charter business, which has apparently been short of capacity for over a year. The type will enable ATA to serve more destinations around the world on a non–stop basis. The carrier said recently that the commercial and military charter contracts already secured have effectively “sold out” the 500s and that further fleet expansion may be considered in 2000.

Virtually all of the L–1011 fleet is owned, as are two of the 757s and nine 727s — the latter because they were taken off operating lease over the past year or so. In December 1998 Amtran raised $125m in senior unsecured debt to purchase and modify the -500s and one 727 and subsequently also secured a new four–year $75m bank credit facility. In August 1998 the company had to shelve a planned equity offering of 3.7m common shares due to unfavourable market conditions, but the debt issue and continued strong financial performance have meant that those plans will not be revived this year.

| Current | Orders | |||

| Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | ||||

| fleet | (options) | |||

| 727-200 | 24 | 0 | No plans to retire 727 fleet | |

| 757-200 | 9 | 3 | Two in 2H99, one in June 2000 | |

| L-1011-50/100 | 14 | 0 | ||

| L-1011-500 | 2 | 3 | Two in 3Q99, one in 4Q99 |