Latin America - who will succeed?

July 1999

Last month Aviation Strategy looked in detail at the alliances that are taking place both between Latin American and US airlines and also among the Latin American carriers. This follow–up article takes an overview of the Latin American market and the prospects for the airlines serving it.

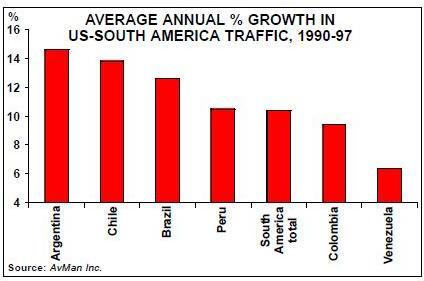

Since 1990, when American Airlines bought Eastern’s Latin American routes for $400m, the face of Latin American aviation has changed dramatically. American’s entry coincided with the adoption of democracy and the free market system from Mexico to Argentina. Traffic between the US and South America has doubled in the intervening years, and it has evolved into one of the world’s fastest–growing commercial airline markets.

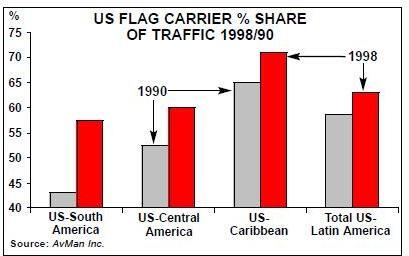

The total US–Latin America and Caribbean market has grown from 26m to 36m passengers in 1990–97, and the US carriers’ market share has gone from just under 59% to 63% (and in the US–South America market from 43% to 53%). This has become the most exciting commercial aviation market in the world — for the past three years more US citizens have travelled between the US and Latin America than between the US and Europe.

1998 was admittedly a difficult year. The final numbers for 1998 are not yet available, but during the first 10 months total traffic grew by only 5.7%. But this is still a vibrant number compared to, say, domestic US traffic, and it is clear that the region’s various financial crises did not impact passenger volumes in anything like the way that the Asian crisis reversed passenger growth there.

Again, US carriers continued their market share growth by stealing four percentage points in 1998. As Delta and others expanded aggressively they added 21% to capacity, depressing yields in many markets and contributing to the financial crises at several Latin American airlines.

But US–Latin American traffic is only half the story. A recent study carried out by AvMan showed that 80% of all Latin American commercial aircraft landings and take–offs never touched the US — in other words, the activity was entirely within the region.

The de-regulatory process

While all of Central America has “Open Skies” with the US, so far only Peru in South America has signed up to such an agreement, though Chile will follow soon. Argentina has agreed to Open Skies by 2003 but talks have recently fallen apart over the timetable. Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay are all denoted as Category 2 or 3 — which means the national carriers cannot add capacity to the US, because of safety and security concerns. While that situation exists, Open Skies with the US would be suicidal.

Within the region, the five nations of the Andean Pact (Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia) signed Open Skies for their airlines in 1994, since when traffic within the region has exploded. Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia and Chile) has moved in that direction with the December 1997 Fortaleza Agreement, a form of Open Skies allowing airlines in the region to fly any route not included in the individual bilateral.

Most countries have introduced some form of deregulation/liberalisation domestically, from Mexico to Argentina. Argentina, Peru and Venezuela have also liberalised foreign ownership, and Peru has experimented with cabotage for foreign carriers.

Alliances and consolidation

Latin America has been going through both deregulation and privatisation, which has opened up new commercial opportunities at the same time as traumatising some of the incumbents. As Enrique Cueto of LanChile stated recently: “To attract adequate financing, airlines must operate in a liberalised environment”. The only problem is surviving long enough.

All the Latin American flag carriers are now privately controlled, although governments retain minority positions in AeroPeru, Aerolineas, LAB, Ecuatoriana and others. Unlike in Europe, some flag carriers have been allowed to go bankrupt — e.g. Viasa in Venezuela and Air Panama. But there has also been some tacit support for others that got into trouble. Varig has just has its balance sheet strengthened through the swapping of government liabilities for equity, and Transbrasil has received similar treatment.

There is scope for more equity investments from US Majors. Continental is a high–profile player at the moment, though it pulled out at the last minute from its 49% investment in AeroPeru, apparently because the government refused to place a six–month moratorium on new start–ups. Last year Continental also pulled out of a 19% investment in Colombian carrier ACES after it seemed the deal was settled. Now Continental is looking at the largest Colombian carrier, Avianca — which is the only major airline in the region without an alliance partner (its code–share with American never having been approved) — and at ASERCA, which has just acquired 70% of Air Aruba, and at Grupo TACA (which has backed another Peruvian start–up, TransAm).

ACES, meanwhile, continues to seek equity from American, Delta or United. American is interested in Aeropostal and maybe in LanChile in order to consolidate its Southern Cone position as part of an agreement involving Aerolineas. Delta and United might decide to take a position in the CINTRA IPO later this year and end up with equity in Aeromexico and Mexicana respectively. Delta is also supposed to be a potential investor in Transbrasil.

At this point, one question needs to be raised — will consolidation and failure of national carriers bring a reaction from the regulators to re–regulate, and will we see a spate of new government–backed airlines?

It’s not likely throughout the region, but we are seeing examples in Ecuador (where the air force–backed TAME is now flying international routes and has announced that it wants to serve the US) and Peru (where TAN, another air force–backed airline, has announced that it is looking to acquire 737s). Certainly the potential for near–monopolies exist and this could generate consumer backlash — something we are beginning to see in the US.

A future trend may well be for Latin carriers to form holding companies — owned by the carriers and other investors — in order to generate economies of scale and generate critical mass, enabling them to negotiate from strength. A second step in this might be public offerings within the region and possibly on Wall Street. CINTRA in Mexico has already proved that bringing two major airlines in that country under the direction of a holding company can produce excellent results within, if not outside, the home country. And TAM Group in Brazil is a form of holding company that has worked extremely well in the region.

Another important force in Latin American aviation is presented by the latest wave of start–ups. For example, Southern Winds in Argentina has recently fallen out of a strategic alliance with Aerolineas, but is rapidly adding 50–seater CRJs to its fleet and is opening up new routes in the southern part of the country. It doesn’t necessarily discount forming other alliances, but by opening up routes not served by any airline it is stimulating and creating its own market in the same way that Southwest has.

AVANT in Chile, which recently acquired National Airlines (another domestic start–up), is owned by Turbus, a major bus company which has some interesting potential for combining bus and air and reaching hundreds of small communities with low cost transportation.

LAPA, (Lineas Aereas Privadas Argentinas), a 737 operation in Argentina, has carved out more than 30% of the domestic market and is planning to start US service (to Atlanta) later this summer. LAPA has demonstrated that frequency and price stimulation work and it is the launch South America customer for the 737–700.

Survival/success/failure

There are three kinds of airlines that will survive and may prosper. The first of these are those airlines with a strong US and/or global equity partner, which are also able to form regional alliances. Examples include:

- Varig, a member of the Star alliance, which has not sold an equity stake but is talking to Lufthansa about it;

- Aerolineas Argentinas and LanChile, which are likely to have a regional cross border equity relationship as well as a major partnership with American;

- COPA, because of its equity relationship with Continental and potential for participating eventually in the Continental/ Northwest/KLM partnership;

- Grupo TACA, which although it has not yet announced an equity investment by a US Major, is a very likely candidate and may join Aerolineas as an equity partner of American, or COPA as an equity partner of Continental; and

- On the cargo side, Colombia’s TAMPA and its equity partner Martinair is an example of the type of cross–border equity arrangement that could succeed in this sector.

The second type are airlines that have a strong management team and proven track record, as well as code–share and/or other alliances with one of the US or European Majors — but without any equity (as yet). Examples are:

- ACES in Colombia, which has a code–share agreement with Continental and has been looking for an equity investor;

- Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela, the born–again Venezuelan carrier that has agreements in place with Delta, Air France and (subject to government approval) with American;

- TAM Group in Brazil, which has a code–share with American and has proven that it can be profitable in the worst of times in its core market, Brazil and Mercosur;

- Transbrasil, which has a code–share alliance with Delta and has shown signs of a real turnaround during the past 12 months; and

- BWIA (which has just reported a $9m net profit in 1998, the first in its 50–year history) and Air Jamaica (yet to produce a profit, but the airline has a strong presence and a young management team that is doing a lot of things right) in the Caribbean, especially if they get together and form a regional holding company or other partnership and are successful in finding marketing and/or equity partners.

The third kind consists of the niche carriers with recognised strong management, which have developed a strong market presence at home without relying on an alliance partnership with any one — but which are strong candidates to sign one because of their strength in domestic and regional markets. Examples include:

- AVANT in Chile;

- AeroRepublica in Colombia;

- LAPA and Southern Winds in Argentina; and

- Air Caribbean in Trinidad & Tobago.

As for potential failures, all carriers are potentially at risk in such a competitive environment, but Lloyd Aero Boliviano and Ecuatoriana — both under VASP management — are obvious candidates, as is AeroPeru after the failure of the Continental deal. One observation is worth making — absentee owner–managers don’t work, as witnessed by Iberia’s investments in VIASA and Aerolineas Argentinas, and Aeromexico/Delta’s investment in AeroPeru.