Smarter strategies for new entrants

July 1998

As the aviation industry enters the last phase of the current cycle, the dynamics of competition will change. In this article Louis Gialloreto of McGill University looks at how the strategies of new entrant airlines may alter during the next few years.

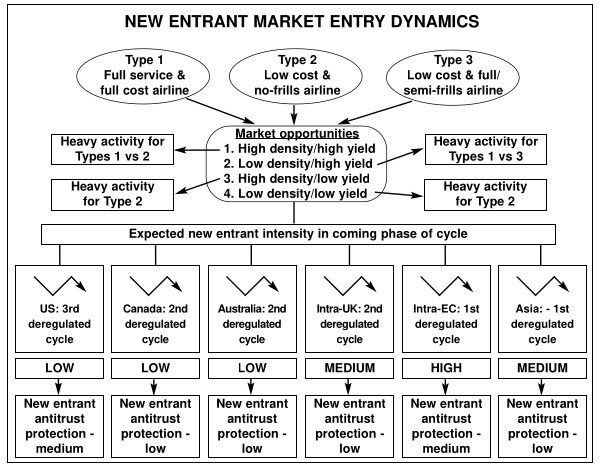

Traditionally, there have been two types of new entrant into the deregulated aviation market (see diagram, right) — the traditional low cost, no–frills airline (Type 2) and the low cost, full- to semi–frills type carrier (Type 3).

In the last two deregulated cycles the US domestic industry has produced a number of each type of new entrant, although very few have been sustainable propositions long–term. Even Southwest cannot be held up as a successful new entrant in this period since it started life eight years prior to US deregulation.

Nevertheless, the experience of the US reveals certain generic access strategies for new entrants. These include:

- Offering low frills, the lowest costs and fares, and having dominant capacity in city pair markets.

- Offering low costs, mid–level fares (below majors but above some Type 2s) and a level of service profile that allows brand differentiation with niche share in multiple city pair markets.

- Offering mid–costs, mid- to full–fares (at par with majors) and an above market service/brand profile, with a small share of limited dense/high yield markets.

These various strategies are applied by new entrants in well defined market city–pairs, with four key permutations of density and yield (see diagram). But the problem is that these generic strategies are often applied incorrectly, leading to inevitable new entrant failure.

Survival questions

While different stages of the deregulated cycle will always offer differing levels of encouragement to new entrants, one key question remains: will the level of survivability increase — i.e. will we get smarter new entrants in the future?

The problem is that very few new entrants devise a sustainable avowed strategy and then stick to it over time. Despite the example of Southwest, all too often others move away from their initial strategy as a soon as some limited success is achieved. For example, new aircraft are often used to add limited capacity in a new city pair market, as opposed to using aircraft to increase capacity/frequency in an already served city pair.

At Southwest the choice would be clear, but all too many others would be tempted to add destinations in order to reinforce early success in an existing market. The old People Express, Greyhound in Canada and many others have fallen victim to this mistake.

When deciding on a strategy to stick to, new entrants must ask themselves two questions: when is low cost low enough to compete, and what market share is enough market share in a city pair? The answer to the first question is clear — the only long–term sustainable strategy is to have the lowest cost of any player in the city pair market. And the worse the economic situation the truer the dictum.

As for premium services, it seems that with few exceptions the majors (Type 1s) are able to play a deregulated war of attrition fast and hard enough to reduce, if not eliminate, the new entrants’ chance of establishing and leveraging a premium brand reputation. This being the case, the only sustainable proposition in deregulated markets is an airline that has high volume, the lowest costs (and standard fares) and a high market share of a city pair combination.

How low can you go?

So just how low is low enough? Currently, Southwest’s cost per ASM is 6.9 cents, while United is at 9.5 cents and American is at 10.5 cents. Can a viable airline be run at less than 6.9- 7.0 cents/ASM? American Trans Air, a former charter carrier, has recently embarked on a frontal attack strategy on majors on key city pairs and claims a cost/ASM of 6.1 cents.

How successful will American Trans Air be?

The theory the airline seems to be relying on is that the majors will not be too competitively destructive in their core markets and so, within reason, will tolerate a small niche player in dense city pairs.

Also, the major airlines are trying hard to maximise the leverage of frequent business travellers (9% of US air travellers account for 44% of total revenue), and thus they do leave some of the low value traffic for others.

Wounded ducks and regulation

A failing major airline has always caused major headaches for the other majors, as this provides market access opportunities for new entrants. This upturn, however, there have been fewer wounded ducks to replace in general. While Asia and the European markets are full of wounded ducks waiting to fall, North America has far fewer than the last time around the aviation cycle.

Overall, the situation for new entrants can be summarised as follows: reduced market access opportunities in the second and third deregulated cycle markets but plenty of opportunity in Europe’s first deregulated cycle and Asia’s first substantive recession.

This brings us to the great potential equaliser between incumbent and new entrant, namely regulatory protection of new entrants. The US’s Democratic administration has, throughout its term, signalled its willingness to block anti–competitive market action by majors against fledgling start–ups.

In Europe the EC is making similar noises, albeit in an uneven way, and in Asia — as the losses mount — new solutions are being sought in what are mostly regulated markets.

Can new entrants depend on protection from unfair competitive practices? On balance the answer would appear to be: not enough to bank on. As such, new entrants have to do a better job in finding and applying the right strategy for the markets they are entering. In short, they have to get smarter.