Impossible to squash the Frontier spirit

July 1998

The combined effect of WestPac’s shutdown and United’s modified behaviour has been to improve Frontier’s prospects dramatically. With the help of a fresh equity infusion, the Denverbased carrier now looks set to restore profitability through modest growth, cost–cutting and new marketing initiatives. But given the dismal survival record of US start–ups, can Frontier succeed?

The airline that we are talking about here is actually Frontier Mark II — the original carrier ran into financial difficulty and went bankrupt in 1986, after an unsuccessful rescue attempt by People Express (which was subsequently taken over by Texas Air). The new Frontier, which was set up by the president and other top executives of the old company, began 737 operations in July 1994 from its predecessor’s base at Denver.

Like many of the other 1993–95 crop of low cost carriers that took to the air when the barriers to entry were at their lowest ever, Frontier had a shaky start because it was very thinly capitalised and initially chose the wrong markets. It started operations on very thin and weak routes, trying to feed to United at Denver, but United did not need another feeder there and losses accumulated.

In October 1995 Frontier raised $7.3m in a common stock offering and changed its route strategy. The carrier decided to enter many of United’s largest markets out of Denver, offering typically 30% lower fares but relatively low frequencies, so as not to provoke its large competitor.

Frontier had already begun service in some bigger markets that had been abandoned by Continental. The new strategy meant the addition of Chicago/Midway and Phoenix, followed by the West coast (Los Angeles and San Francisco) and Salt Lake City and Minneapolis/St. Paul in the autumn of 1995. Numerous small markets in North Dakota and elsewhere were abandoned in 1995 and 1996.

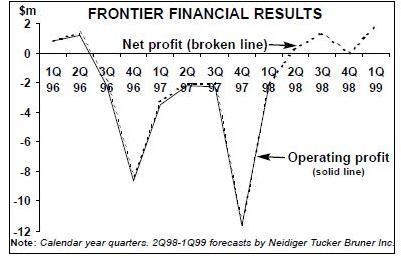

As a result, Frontier made its first quarterly profit in January–March 1996, as load factors surged by 15–24 points from the previous year’s pitifully low–40s. The turnaround was consolidated with a $1.3m net profit in the June 1996 quarter. Frontier was lucky in that it managed to raise $2.7m additional capital through a private placement in April 1996, just before the industry sector was hit by the ValuJet crash and grounding. This enabled it to order more aircraft and enter three new major markets — St. Louis, San Diego and Seattle/Tacoma — in the spring of 1996.

The carrier escaped the worst of the “ValuJet effect”, in part because of its operations in the West (where the travelling public’s perception of low–cost carriers is different than on the East coast) and probably also because of its old–established name and relatively low profile.

The Denver area had become a little crowded after WestPac began low–fare operations from nearby Colorado Springs in April 1995. But Frontier’s slow growth and position at a premier hub gave it a solid image. It was regarded as one of the most likely survivors in the post–ValuJet era. But instead of consolidating recovery, Frontier plunged back into losses in the second half of 1996, and since then it has yet to report a profitable quarter. The initial losses were blamed on a “massive abuse of power” by United, including alleged capacity–dumping, below–cost pricing and other “strong arm” tactics at Denver, which began in the summer of 1996. The competitive pressures continued in 1997 when United rubbed salt into the wound by bringing the Shuttle to some of the Denver markets.

The next ordeal for Frontier began about a year ago when WestPac, in search of larger markets, decided to move its operations from Colorado Springs to DIA. This immediately led to an agreement to merge Frontier and WestPac through a $41m stock swap deal and code–sharing, which began on August 1 1997. But the merger talks failed at the end of September and WestPac filed for Chapter 11 on October 4, and Frontier then had to compete head–on with a bankrupt carrier.

Frontier president Sam Addoms noted that the market had been “supersaturated with excess capacity” at deep–discount prices in the wake of WestPac’s operational shift to Denver. As a result, Frontier incurred a staggering $11.5m net loss in the December quarter.

The airline reported a reduced $2.1m net loss for the March quarter, down from $3.3m a year earlier. The improvement was attributed to “a return to normality in the Denver marketplace” following WestPac’s shutdown in early February.

The bulk of the loss was incurred in January, while the month of March actually produced a small profit.

Frontier’s prospects have also improved because of Washington’s determination to crack down on predatory behaviour by the major carriers. This and WestPac’s demise were instrumental in securing an equity infusion in April, which gave Frontier adequate cash reserves for growth. In the middle of the WestPac battles last autumn, Frontier ventured into the East coast markets with services to Boston, Baltimore/ Washington and New York LaGuardia, so it is now a transcontinental carrier, as well as the second largest operator at Denver. About to celebrate its fourth anniversary on July 5th, Frontier is now regarded as an “old–timer” in the low–cost carrier circles. But what strategy will it employ to make the most of the fresh start it has just secured?

David and Goliath battles

Frontier competes head–to–head with United in virtually all of its markets — the only exceptions are two secondary routes from Denver plus Chicago, where the two serve different airports. So getting the competitive and predation issues resolved is vital for the small carrier’s survival.

The airline made formal complaints to both the DoT and DoJ in early 1997, charging United with capacity–dumping and predatory pricing. The most heinous of the alleged crimes took place in the Phoenix and Las Vegas markets, where the Shuttle took over United’s existing services, boosted frequencies and slashed fares. For example, the Shuttle boosted Denver–Las Vegas capacity by 32% and cut the one–way fare, already barely profitable at $59, to $49. As a result, Frontier had to pull out of the Las Vegas market (which had little connecting traffic), and the fare is now $100.

Frontier’s complaints were actually instrumental in spurring the regulators into action. The DoJ consolidated the various airlines’ complaints and is now processing the material raised in the hearings.

In April the DoT came up with proposals for rules to prevent predatory behaviour, which are currently in the commenting period. The DoJ has the power to fine United, though Frontier is merely seeking a level playing field.

The good news on this front is that, as the DoT predicted, the mere threat of new rules and serious investigations has made carriers like United clean up their act. Frontier says that United has been noticeably less aggressive in its pricing in recent months. It now hopes that the regulators will also tackle issues like exclusive corporate contracts and bias in CRS systems.

A merger between Frontier and WestPac would have made great economic sense, giving two small carriers critical mass to compete effectively against United. But the two carriers with the same low–fare philosophy were totally incompatible.

One problem was that the code–sharing involved Frontier having to reschedule its flights to “undesirable” off–peak times to mesh with WestPac’s. The volume of traffic “would have been good for a couple”, but the two were clearly not meant to be a pair. Their differences ranged from corporate culture to marketing, while WestPac’s financial difficulties were also a stumbling block.

Frontier’s problems began in earnest on November 16, when the code–sharing ended and WestPac had completed its move to DIA. About two–thirds of Frontier’s capacity competed with WestPac’s. Although Frontier had been able to reschedule its flights to more optimal times, the excess capacity in the markets led to November and December load factors plummeting by 7–8 points. In an effort to raise cash, the bankrupt carrier also launched numerous deep–discount fare sales, which Frontier had to match to stay competitive.

To add insult to injury, after it ceased operations WestPac made a deal with United enabling the major to accommodate all of the 60,000- 70,000 WestPac ticket–holders. The relations between the two companies had deteriorated further when in late November Frontier made an unsolicited bid for WestPac, countering another offer favoured by the management.

But WestPac’s disappearance had an immediate favourable impact on Frontier’s load factors and average fares, and by May the situation had returned to near normal. In April, when the company disclosed that the March load factor exceeded 60%, analysts started talking about return to profitability in the June quarter.

New funding and expansion

The brightened prospects enabled Frontier to attract a $14.2m equity investment in April from Wellesley, Massachusetts–based B III Capital Partners, which purchased 4.6m newly issued shares and received warrants to acquire additional shares. The purchase was for investment purposes only, though B III also got the right to designate two board members.

This was a major vote of confidence in Frontier’s prospects, significant at a time when start–ups generally are still finding new finance hard to come by. Frontier reckons that the publicity generated when its name was frequently mentioned in the context of the Washington hearings and its increased visibility on the East coast also helped.

The proceeds enabled Frontier to rebuild its balance sheet, which was seriously weakened by the battles with WestPac. It had only $2.9m in unrestricted cash at the end of 1997, compared with $8.6m a year earlier. The new investment was needed because Frontier had received only $5m of the $15m loan that Connecticut–based Wexford Management had earlier indicated that it could provide (talks on the additional funding were terminated by mutual agreement in February).

Frontier’s fleet is currently made up of seven 737–300s, four of which were added in the past year, and seven smaller 737–200s. All are on operating lease from various lessors. The carrier is “aggressively seeking” three more 737s, which it would like to introduce by the end of the year.

In recent years growth has been constrained by the lack of aircraft. This was in part due to inadequate funding but, over the past year, mainly due to lack of aircraft availability. A good opportunity was lost when WestPac’s aircraft became available, but Frontier could not take them straight away. It has been a tight year for 737s, but the company believes that the situation is easing up.

Frontier would like to obtain another 8–9 737s in 1999 and 2000, which would facilitate continued growth but at a modest, manageable rate.

This would take it to the 25–aircraft mark that analysts believe might be the optimum size for the company, giving it sufficient economies of scale but not provoking United.

Much of the recent focus of route restructuring and expansion has been to target the higher–yield business travel market. The longer–range 737- 300s delivered last year were used to expand service to the East coast: Boston in September, Baltimore in November and LaGuardia in December. In November Frontier also added frequencies in its best existing business markets — Los Angeles, Salt Lake City and Phoenix — but terminated service to St. Louis and San Diego. But this month (July) Frontier will restore service to San Diego, bringing to 15 the number of cities served from Denver, and boost frequencies to four cities in the West. The three additional aircraft, if obtained, will be used to boost flights to the East coast and to possibly add two new destinations.

Access to slot–controlled LaGuardia was gained when Washington intervened to open up New York’s premier domestic gateway to some low–cost services. However, Frontier was authorised to operate only three daily flights, when at least five or six would be necessary to attract sufficient business traffic.

But Frontier still operates only two daily flights into LaGuardia. The official explanation is its aircraft shortage, but the carrier now admits that the market has taken longer to “mature” than the Boston and Baltimore routes. The difficulty and cost of advertising effectively in the New York area is one reason. Frontier says that the market is “coming along very nicely”. Analysts are not totally convinced but, as one put it, LaGuardia is “certainly better than flying to Fargo, North Dakota”.

Also on the positive side, the East coast services are attracting a growing volume of connecting traffic to the West coast. About 20% of Frontier’s total traffic is now connecting. With additional aircraft, the company would like to schedule flights so that every incoming flight at DIA connects with five outgoing flights (the number is currently about three).

Successful cost-cutting

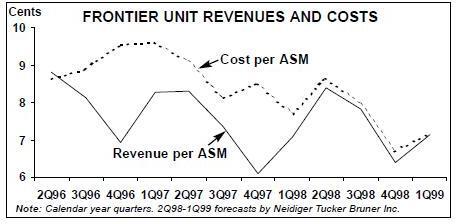

While battling it out with United and WestPac, Frontier managed to reduce its costs substantially — a major factor enabling profitability to be restored now that the competitive situation has stabilised. Its unit costs fell by 20% to 7.68 cents per ASM in the March quarter (from 9.61 cents a year earlier). This was attributed to the operating efficiencies of the growing late–model 737–300 fleet, coupled with economies of scale.

The airline has lined up another $5.1m or 3% annual cost savings through three actions taken this year. First, in April it reduced its travel agent commission rate from 10% to the industry standard 8%, saving about $2.3m annually. Second, in June it renegotiated its insurance premiums, saving about $1.8m annually.

Third, effective September 1 1998, Frontier will in–source its “under the wing” ramp services (baggage and cargo loading, water provisioning etc) at Denver, in an effort to reduce costs and improve quality of work. This requires an investment in the region of $1m, which the company could not previously afford, but the move is also expected to generate $1m annual cost savings.

Going up-market

The past year has seen a concerted effort by low–cost carriers in the US to focus on the higher yield passenger segment. Most notably, AirTran has introduced a no–frills business class and an FFP, while others have joined CRS systems and begun paying commissions to travel agents.

Frontier has actually been doing many of those things virtually since its inception. Its schedules and fares are displayed in all four of the major CRSs. It participates in Continental’s OnePass FFP. It offers ticket–less reservations, assigned seating and limited meal service. And the desire to capture more business traffic has led to various new product and marketing initiatives.

Frontier is at present intensively studying the introduction of a first–class section on its fleet. This is a very difficult issue to decide. On the one hand, a dedicated cabin section could really help attract high–yield passengers, given that low–cost carriers like Frontier can also offer those seats at much lower fare mark–ups ($25 in AirTran’s case) than the high–cost majors can. But there would be a penalty in terms of lost seats in coach class (or unacceptably low seat pitch) and costs would rise.

There are plans to sign up marketing/code–share partners, both international and domestic, at DIA and elsewhere. At present Frontier has only one (minor) code–share partner, Aspen Mountain Air.

Prospects

After two years of net losses totalling $31.3m, Frontier looks likely to report a small profit of somewhere between $250,000 and $500,000 for the quarter ended June 30. This would actually be less than half of what some analysts had predicted in April, because the May load factor (59.6%) was a little lower than expected.

A more stable competitive environment and continued low fuel prices should ensure that Frontier will be able to fully capitalise on the peak summer season. If it finds the three additional 737s by year–end, the prospects for the peak skiing season (March quarter) also look promising. Two Denver–based stockbroking companies, Cohig & Associates Inc. and Neidiger Tucker Bruner Inc., predict net earnings in the $3m-$3.4m range for the financial year ending March 31, 1999.

Making any longer–term predictions seems rather futile, given the instability that has characterised the new–entrant airline sector in the US. ValuJet was the darling of Wall Street before its spectacular downfall. Next, WestPac was regarded as the most likely survivor, but it failed too. Perhaps Frontier’s greatest strength now is its sound business plan and gradual growth strategy.

| Current Fleet | Orders Options | Delivery/retirement schedule/comments | |

| 737-200 | |||

| 7 | 0 | ||

| 737-300 | 7 | 0 | “Aggressively seeking” three more 737s |

| (300 series or advanced 200s with hushkits) | |||

| for introduction by year-end. 8-9 more 737s | |||

| TOTAL | 14 | 0 | would ideally be acquired in 1999-2000. |