Alitalia - a miraculous turnaround?

July 1998

Just 18 months ago Alitalia was one of the European basket–cases, technically bankrupt, riven with labour disputes and embroiled in arguments with the European Commission over its L2,750bn ($1.5bn) state aid application.

Now, having returned to profitability in 1997, it has completed a successful rights issue — which will reduce state ownership to 51% — and has a market capitalisation twice that of its prospective European partner, KLM.

Is this a miraculous turnaround?

Alitalia management and IRI (Instituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale, the state holding company) have moved with remarkable rapidity in part–privatising the airline. As part of the restructuring plan agreed with the EC, IRI announced that it would be recapitalising the airline early this year, and on May 18th it succeeded in placing a rights issue with institutional investors. The issue had a rather complicated structure but in essence IRI sold about 14% of the airline’s stock to institutional investors, increasing the free float in the airline from 15% to 29%. IRI’s share is dropping from 85% to 51%, the minimum under current Italian law. The remaining 20% of the carrier’s stock was allocated to staff. Moreover, Pietro Ciucci, CEO of the IRI Group, announced in May that Alitalia would be fully privatised by the end of 1998.

As of June 23rd Alitalia’s stock price was L6,000 on the Milan exchange, implying a market capitalisation of L9,420bn ($5.2bn). This compares with a $3bn stock–market valuation for KLM or $11bn for BA. KLM is trading on a prospective p/e of 8.5/1, BA on 11/1 Alitalia on 24/1.

There may be a technical reason for Alitalia’s high rating — Italian fund portfolios traditionally include all shares in the MIB30 (the 30 largest quoted companies). As Alitalia now falls into that category, they have been active in making purchases. Also, p/e ratios in Italy tend to be higher relative to the UK or US because accounts traditionally have been compiled in order to minimise tax liability rather than satisfy equity markets, so there is a motivation to suppress reported profitability. Investors compensate for this when purchasing stock.

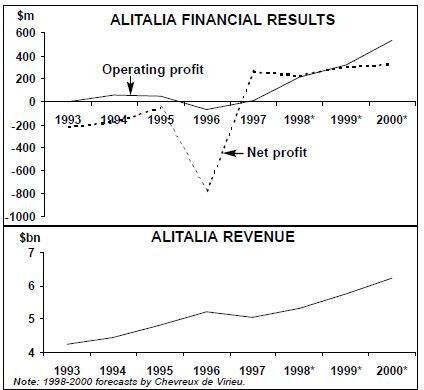

Basically though, Alitalia’s valuation remains puzzling as it has only been profitable for one year in the 1990s. It is worth taking a slightly more detailed look at the changes in Alitalia’s P&L between 1996 and 1997 when Alitalia’s bottom line improved by L1,641bn ($912m) to a net profit of L437bn ($243m) — see table, left.

On the operating level, however, the improvement was just L401bn, largely resulting from lower per gallon fuel prices. The operating margin was a sad 0.2%. Net financial charges were down by L190bn, the result of debt write–down following the injection of the final tranches of the L2,750bn in state aid from IRI. The giant change though was in extraordinary items where there was a positive turnaround of L1,282bn. This came about because in 1996 there were extraordinary costs of L920bn, mostly relating to the employee stock plan and redundancies, while in 1997 there was an extraordinary gain of L362bn, relating to profits from the sale of its shares in Aeroporti di Roma (ADR), Galileo and Malev.

For this year Chevreux de Virieu is forecasting a substantial improvement in operating profit to L367bn ($204m) — a 4% margin — with net profit slightly higher at L390bn. So how robust is Alitalia’s turnaround strategy? Alitalia’s turnaround has followed three basic stages — labour, fleet, markets.

Teamwork

Alitalia’s recent achievement in harmonising union relations and lowering labour cost is remarkable given the strength of the unions there and the restraint of having to change laws in order to reduce entry–level salaries or modify agreed working hours. The solution was Alitalia TEAM, created in 1996 to absorb the domestic airline Avianova and act as low cost subsidiary. At the end of 1997 some 1,500 flight and cabin crew members had been transferred to TEAM, leaving 4,600 at the parent company. 56 aircraft are now operating under the TEAM logo, including MD–80s, A321s and 767s.

With union agreement (at eight of the company’s nine unions), the plan is to relocate all of Alitalia’s employees to TEAM by the year 2000. Through increased productivity Alitalia expects to reduce its unit labour costs by about 10% between now and 2001, having already brought them down by 20% since 1994 when they were the highest in the European industry. Total savings are forecast to be L1,500bn ($833m). If all goes according to plan Alitalia should be competitive on labour costs with the best of the Euro–majors by the turn of the century.

Credit for the change in union relations must go to Domenico Cempella, who was brought in to replace Roberto Riverso as CEO in 1996. Cempella’s understanding of the union mentality and his long–time association with Alitalia (he started as a check–in clerk in 1958) and ADR evidently was more effective than the technocratic approach of his predecessor who, having come from the information technology industry, was frustrated and bewildered by union intransigence and Roman politics.

The cost of union compliance is, however, somewhat disguised by the free share distribution to employees. These shares are worth almost $70,000 per employee on current valuation — about the same as the average annual salary for a steward or stewardess at the old airline. But then the value of stock can fall as well as rise. According to Cempella, a cultural breakthrough was made in 1996 when Alitalia management started to think of liberalisation as an opportunity instead of — or at least as well as — a threat. The restrictions imposed by the EC as conditions for the state aid approval can now also be seen as partly contributing to Alitalia’s turnaround. These included the requirement that until the end of 2001 capacity growth (in terms of seats and ASKs) remained well below the level of market growth.

Asset rationalisation

The table on page 9 illustrates the effect of the EC–imposed constraint. In key sectors like intra–Europe and the North Atlantic Alitalia’s 1997 traffic hardly moved or even declined, in sharp contrast to the boom conditions enjoyed by other European airlines — but because of capacity reductions, load factors were pushed up to close to the European average for the first time.

Higher load factors have created the conditions in which effective yield management can be implemented. Alitalia puts great emphasis on its new “True O&D” revenue system from Sabre Technologies. Following the introduction of the system in mid–1997 it started recording 7–10% annual increases in unit revenue (per ASK) on domestic routes and 10–12% increases on international services.

Whether these increases represent a one–off adjustment or whether Alitalia can continue to push up yields (obviously at a lower rate) is unclear. But Alitalia is obliged to focus on yield management as it is prohibited from adopting price leadership strategies by the EC until 2001. Also, as Alitalia refocuses its business from Rome to Milan, the scope for using yield management increases as the passenger mix should evolve from being predominantly VFR and leisure to business–related.

Over the past two years Alitalia has made a great effort to rationalise its fleet, which, like Iberia’s, used to have models from the three manufacturers in each possible aircraft type. 14 DC–9s and 14 A300s have been sold while orders for five MD–80s and 15 A320s were cancelled. Its short/medium haul fleet is still split between the MD–80s and the A320/321s, while the long hauls have operated with three types — the 747–200, 767ER and MD–11s.

The delivery schedule for the next three years is very modest, raising concerns about Alitalia running into capacity constraints. However, there is potential for further rationalisation of the current fleet. Utilisation of the narrowbodies has risen from 7.1 hours/day to 8.25 since 1995, but this is still modest by industry standards despite the relatively low average stage length. The long haul network remains diffuse: Alitalia operates to 38 points outside Europe but cannot offer daily service on the large majority of these routes. An objective assessment of route profitability would probably lead to route closures or consolidations.

Arrivederci Roma, buongiorno Milano

Alitalia’s expansion at Milan is critical to the airline’s success. It symbolises a move away from the political centre of Italian life to the commercial centre and will provide Alitalia will the chance to recapture the higher yielding traffic it loses to Swissair’s Zurich hub and Lufthansa’s Munich hub.

Northern Italy generates about 67% of total Italian international aviation revenues compared with 18% for the Rome region and 15% for the rest of the country. Alitalia itself admits that it captures only a third of the Northern Italian revenues (other sources have estimated Alitalia’s share to be even lower), but it now states that it will recapture the lost traffic when it builds its first genuine hub at Milan Malpensa.

The hub plan is to build a four–wave system of connecting short and long haul flights. This compares, for example, with seven waves at Zurich but there will be 44 movements per wave compared with 22 at Zurich.

The new facilities at Malpensa are due to open at the end of this year, so presumably the Alitalia hub system should be fully operational by the summer of next year.

Alitalia is in the process of transferring 10% of its Rome services plus most of its operations at Linate airport — which is close to the centre of Milan — to Malpensa, which is 65km away and presently very poorly served by road and rail links. In a blatant piece of flag–carrier support the Italian authorities have decreed that all services with passengers flows of 2m passengers a year — i.e. all services apart from Milan–Rome — will have to move from Linate to Malpensa by the end of the year. Foreign airlines are not at all happy about this and several of the leading European airlines, including KLM, have made official complaints to the Commission.

This traffic policy conveniently also protects Alitalia’s Rome–Milan shuttle, which remains at Linate as does Air One’s competing service. However, it now becomes very difficult for Air One to link up its services with Swissair, a potential investor in the Italian new entrant.

Indeed, Alitalia’s domestic dominance remains one of its key strengths. Although its share of domestic capacity has fallen from 95% of the total in 1995 to 75% today, a series of formal and informal alliances with the regional carriers — Minerva, Meridiana, Azzurra, etc (see Aviation Strategy, February 1998) — means that it still exercises extensive control over the domestic market (which with 18m passengers a year is the third biggest in Europe after France and Germany).

Alitalia has occasionally pushed its convivial relationship with Italian governments too far. Late last year it was threatened with a court case by the EC over allegations of unfair price–cutting and in 1996 it was fined by the Italian antitrust authority for abusing the slot allocation system at Milan and Rome and imposing illegal ticketing restrictions on travel agents. Other airlines complain about the extreme difficulty of obtaining route authorities.

Although the first ever non–Alitalia scheduled intercontinental flight was made last December — Air Europe to Havana from Milan — a significant opening–up of international markets to Italian competitors is unlikely.

KLM alliance

The consummation of the alliance signed early this year with KLM depended on three factors:

- The now completed part–privatisation;

- The development of Malpensa and the transfer of Alitalia services there; and

- The signing of an open–skies agreement between Italy and the US.

The final condition relates to Northwest’s ability to serve Malpensa (currently it does not fly to Italy and is precluded from doing so by the bilateral) and establish a multi–hub system on both sides of the Atlantic. Continental, which has a limited code–share agreement with Alitalia and which is allied with Northwest, will presumably also fit into this picture.

Having two hubs in densely populated and wealthy but geographically dispersed hubs will enable Alitalia and KLM to maximise their intra–Europe/transatlantic connections, in the process stealing traffic from the other alliances. A joint shuttle between Amsterdam and Milan might be another attractive project.

KLM’s expertise in hub–building should be of direct benefit to Alitalia, though it is interesting that in a recent interview with the Wall Street Journal Cempella emphasised a less tangible benefit of the new relationship with KLM: “A company like Alitalia — one that comes from decades of a monopoly — has no future if it doesn’t start responding to a market that is totally global and liberalised, without protection or help. KLM is a company that is used to being competitive and has an aggressive corporate culture. We expect this to reflect on us as well.”

Changing Alitalia’s corporate culture is fundamental to a continuation of the airline’s recovery. In Cempella the company appears to have found the man for the moment. But politico–industrial intrigue certainly hasn’t disappeared from the Italian state–owned sector — witness the farcical management battles and strategy reversals at newly privatised Telecom Italia. A relapse to the old ways of doing business — which is always tempting if market conditions get tougher — would be a disaster for Alitalia.

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | Change | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| forecast | 97/96 | 98/96 | |||

| Revenues | |||||

| Passenger | 6,230 | 6,530 | 6,995 | 300 | 465 |

| Cargo | 710 | 795 | 859 | 85 | 64 |

| Other revenue | 1,118 | 1,257 | 1,272 | 139 | 15 |

| 8,058 | 8,582 | 9,126 | 524 | 544 | |

| Costs | |||||

| Commission/sales | 1,157 | 1,304 | 1,397 | 147 | 240 |

| Fuel | 825 | 825 | 728 | 0 | -97 |

| Maintenance etc | 610 | 782 | 880 | 172 | 270 |

| Staff | 2,084 | 2,056 | 2,022 | -28 | -62 |

| Rentals | 692 | 663 | 650 | -29 | -42 |

| Depreciation | 467 | 449 | 450 | -18 | -17 |

| Other costs | 2,326 | 2,483 | 2,632 | 157 | 306 |

| 8,161 | 8,562 | 8,759 | 401 | 598 | |

| Operating profit | -103 | 20 | 367 | 123 | 470 |

| Other income | 171 | 325 | 200 | 154 | 29 |

| Net fin. charges | -334 | -144 | -80 | 190 | 254 |

| Pre-tax profit | -266 | 201 | 487 | 467 | 753 |

| Extraordinary items -920 | 362 | 0 | 1,282 | 920 | |

| Taxes etc | -18 | -126 | -98 | 108 | 80 |

| Net profit | -1,204 | 437 | 389 | 1,641 | 1,593 |

| ASK | RPK | Pax load | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (% change 97/96) | factor | ||

| Intra-Europe | |||

| Alitalia | -2.8 | 0.9 | 62.1% |

| AEA average | 5.9 | 10.2 | 63.4% |

| North Atlantic | |||

| Alitalia | -3.4 | -2.1 | 77.5% |

| AEA average | 8.2 | 9.7 | 78.3% |

| South Atlantic | |||

| Alitalia | -1.0 | 7.8 | 77.5% |

| AEA average | 3.7 | 11.6 | 77.3% |

| Total | |||

| All Alitalia | 0.1 | 4.2 | 71.7% |

| AEA average | 6.2 | 9.3 | 72.0% |

| Current Fleet |

Orders Options |

Delivery/retirement schedule/comments |

|

| 747-200 | 8 | 0 | |

| 747-200F | 2 | 0 | |

| 747-300ER | 6 | 3 | Delivery in 1999-2001 |

| MD-80/82 | 90 | 0 | |

| MD-11 | 8 | 0 | |

| A320 | 2 | 19 | Approximately 10 in 1999-2001 |

| A321 | 18 | 4 | Four in 1999-2000. |

| TOTAL | 134 | 26 |