Unions can cash in on equity for productivity deals

July 1998

The unions appear to be revolting again. Union unrest is hitting several of the world major airlines — Air France, Philippine Airlines, Olympic Airways and Northwest being the most prominent.

At first sight this outbreak of industrial unrest could be regarded as a comeback for union intransigence and obstinacy. But each outbreak of union power must be seen in the context of each particular dispute.

As ever, in some of these disputes union intransigence has contributed significantly to the perilous situation the airline finds itself — but in other cases unions are merely responding to last–ditch measures imposed by inept managements:

- At Philippine Airlines, where most of the pilots have been dismissed, the fundamental problems appear to be due primarily to over–expansion. Once downsizing became the only option, clashes between management and unions were inevitable (particularly as unions wrongly assumed that the government would intervene on their behalf).

- The immediate cause of this year’s union problems at Olympic was that the previous management in 1995 and 1996 conceded hugely over–generous pay awards, which the current management have no choice but to try and claw back.

- At Air France management desperately needs to cut labour costs in advance of part–privatisation later this year. In a country where union power has always been strong, Air France’s pilots adopted the sensible tactic (from their point of view) of striking as the World Cup began.

- At Northwest unions threatened strikes after 22 months of mindnumbing negotiations with management. Unions demanded that wage concessions agreed in 1993 to help Northwest avoid bankruptcy be reversed now that the airline has effected a recovery. The dispute was settled in June.

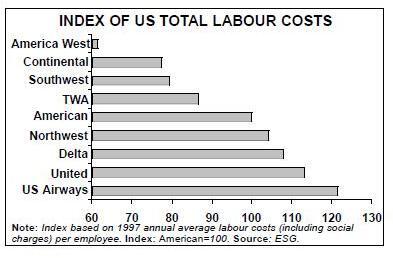

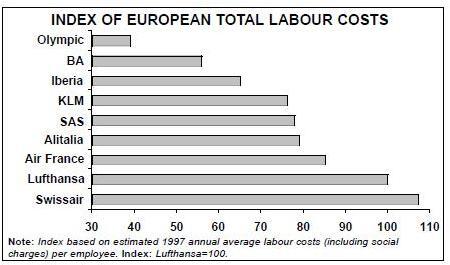

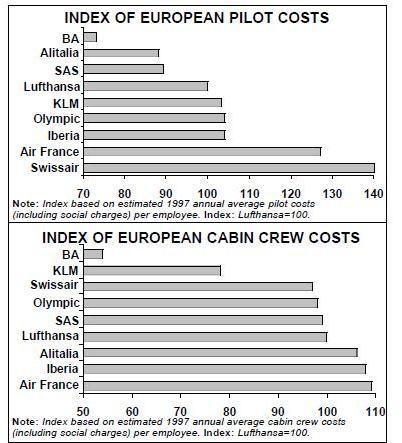

As Aviation Strategy has pointed out before (see February 1998 issue), Europe is steadily eliminating the labour cost gap with the US. And as can be seen in the charts on pages 1–3, there is as much variation in US airlines’ labour costs as there is among Europe’s carriers. But as European airlines’ non labour costs — airport charges, en route fees, ground handling etc — are rising much faster than in the US, the pressure is on Air France, Alitalia and others to cut the one cost that should be completely within their control — labour.

An end to confrontation?

But, unlike the past, the need of Europe’s airlines to cut labour costs does not mean that confrontation with unions is inevitable. There are encouraging signs that unions in Europe are much more mature about compromising when airlines are in a tricky situation.

This does not mean that unions have abandoned their prime purpose: to protect the interests of their members. Unions are always prepared to change their tactics — being conciliatory when needed; taking on aggressive managements at other times. But now some unions appear to be going one step further than just varying tactics. The most enlightened unions appear to be recognising the long–term potential of share ownership in the airline they work in, in return for wage concessions. In short, unions see the chance not just to protect their members, but to make them very rich as well.

Essentially airlines try to “lock–in” unions through equity hand–outs in return for substantial productivity concessions and wage freezes/reduction. But most equity for productivity deals occur when airlines are at their most vulnerable and have little choice but to cut labour costs or go under. Tinkering about on the edges of productivity improvement via shaving the odd percent or two off labour costs does little to save airlines in desperate situations — and unions know this full well.

A classic example is the outline Air France agreement with the pilots (the full deal is scheduled to be completed by the end of August), the main components are:

- Pilots will have their salaries frozen for up to seven years (there may be a review after three or four years, depending on the final negotiations). There will be no adjustments for inflation, so pilots’ salaries will fall in real terms.

- In return the pilots will receive options for up to 15% worth of shares in Air France. The devil is in the detail, which has yet to be defined, but Air France claims the wage freeze will achieve its target of reducing labour costs by FF500m ($83m) per year. At first glance, this seems a better deal for the airline than the pilots. Pilots are giving up hard cash, and in return will receive a stake in one of Europe’s less stable airline. According to unofficial Air France calculations, the company’s share price will have to rise by at least 4% per annum over the seven year period for the return to pilot shareholders to at least equal the value of the real salary reductions they have given up.

It seems a no–lose situation for Air France as it gets the benefit of the wage freeze whatever happens. Risk seems to have been passed on to the pilots, who are “gambling” that shares will appreciate by more than 4% per year for them to break–even.

But looked at another way, the risk is not all that great for the pilots. Even given a mini–recession, over a seven year period the stock–market in France is highly likely to increase by at least 4% per annum. Of course Air France has had a chequered history, and could well under–perform the general market over the next seven years. But, as the saying goes, past performance should be be held as a guide to future prospects. Much of Air France’s past woes have stemmed from two factors — high labour costs and sub–standard, politically–appointed management. But things have changed — management has improved, and unions know that if they deliver on labour costs then the chances are that Air France will have a bright future.

So how well could the pilots do out of the deal? Since it was floated in the 1980s BA’s shares have appreciated at an average 19% per year. By our (admittedly rough) calculations, if British Airway’s pilots had been given 10% of the airline’s stock when it was floated, each of those original pilots would be sitting on shares worth approximately a third of a million dollars (never mind the dividends they would have received).