Allegiant Air: Las Vegas-based niche carrier

January 2007

Allegiant Air: The bets are on this LCC

he diverse US LCC sector has gained yet another variant of the low-cost model: operating cheap, fuel-guzzling MD80s in low-frequency service between small cities and popular leisure destinations and deploying Ryanair-style revenue strategies. Allegiant Air, a Las Vegas-based niche carrier, has staged an amazing comeback with the help of this model since emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2002. The airline has grown at a dizzying pace, is achieving industry-leading profit margins and recently completed an IPO. But will Allegiant be able to replicate the successful Las Vegas formula in the Florida markets? The hitherto very low-profile "hometown America" airline became better known in the context of its parent Allegiant Travel Company's hugely successful IPO on December 7. The offering priced above expectations, raised $94.5m in net proceeds for growth and gave the company a listing on Nasdaq. Post-IPO, the share price has almost doubled, from $18 to $35 as of February 2. The key selling points were Allegiant's four-year record of profitable growth, extremely low operating costs, strong balance sheet and experienced management and financial sponsors. Investors liked the many innovative strategies, including a focus on ancillary revenues and avoiding competitive markets. With 50-plus potential new cities identified by the management, Allegiant was viewed as a promising growth story. But the IPO was also perfectly timed, launched in the wake of a sharp decline in fuel prices in the autumn months. Allegiant's MD-80 fleet would have made the company a tough sell at $70 oil. Allegiant has been well received by Wall Street. By mid-January at least four analysts had initiated coverage of the company, though three of them were from financial institutions that were underwriters on the

T

IPO. There are two "buy" and two "neutral" recommendations — the latter are mainly due to valuation. But Allegiant's longer-term prospects are uncertain because some of its strategies may not be sustainable. How long can it rely on an aircraft type that is no longer in production? How long can it avoid competition in the US domestic market? Many in the industry remain undecided about Allegiant because its model goes against the accepted wisdom that modern fuel-efficient aircraft, high aircraft utilisation and reasonably large markets are critical for an LCC's success in the post-2001 environment. To add to the unease, Allegiant's strategy invokes memories of what US LCCs used to be like in the pre-JetBlue days, when they typically operated old aircraft and many struggled, and eventually disappeared, because they could not find large enough markets. The key thing to bear in mind is that Allegiant is a niche carrier, not a mainstream LCC. This type of model is not going to be significant in the US. But, with around 50 cities already served across the nation and 50-plus more planned, Allegiant is going to be rather large for a niche carrier. The interesting question is: will the innovative revenue and other strategies enable Allegiant to stick to its current formula, or will it have to become like the other LCCs (new aircraft, larger markets)?

Allegiant's background

Allegiant has a little more controversy or colour in its history than the typical US LCC. It has been through Chapter 11. Its two largest investors — CEO Maurice Gallagher and Robert Priddy — were the founders and the leadership at ValuJet, the hugely successful early 1990s LCC start-up that was grounded on safety grounds following its

Jan/Feb 2007

DC-9 crash in 1996. (That said, the executives were not directly blamed, and Priddy oversaw ValuJet's successful transformation into AirTran and remained its CEO for many years). Gallagher was one of Allegiant Air’s original backers when it was founded in 1997, but he did not become involved in management until 2002. The airline operated ad hoc charters and a small network of high-frequency scheduled service focusing on the business traveller in the West, utilising DC9s in a two-class configuration. The strategy was unsuccessful and the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December 2000. As part of the reorganisation, Gallagher's debt was restructured and he injected additional capital, becoming the majority owner and a board director (he took over as CEO in August 2003). A new management team was installed in June 2001, and Allegiant emerged from Chapter 11 with a new strategy in March 2002. In the subsequent years, Allegiant sold equity to four of its senior officers and brought in additional investors through private placements. The present holding company structure was created in May 2004. All of that plus the IPO led to the company looking very strong in terms of its management, financial sponsor line-up and balance sheet. The management team, led by Gallagher, have been together for years, going back to the 1980s in certain instances. Many previously worked together at ValuJet or WestAir, a commuter carrier that Gallagher founded and led in 1983-1992. In addition to Priddy, Allegiant's investors include ex-Ryanair/Tiger Airways executive Declan Ryan and PAR Investment Partners (a US institutional investor with holdings in AMR, US Airways, Alaska, Southwest and Republic). PAR acquired its 4-5% stake through a private sale in conjunction with the IPO. While Gallagher's stake in Allegiant has declined from 80% in August 2003 to about 23% after the IPO, the board and management (including Gallagher) still hold about 56% of the stock. Gallagher has never taken a salary and does not have stock options. As a result of the IPO, Allegiant has one

$000s

400,000 300,000 200,000 100,000 0 2002

ALLEGIANT’S REVENUES..

2007F

$000s

30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 0 -5,000 2002

..AND FINANCIAL RESULTS

Op. result Net result

2007F

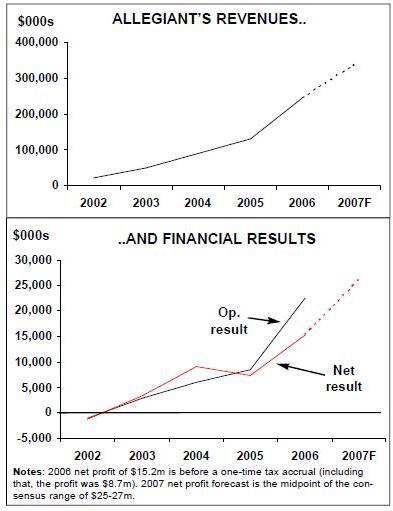

Notes: 2006 net profit of $15.2m is before a one-time tax accrual (including that, the profit was $8.7m). 2007 net profit forecast is the midpoint of the consensus range of $25-27m.

of the industry's strongest balance sheets. Year-end cash reserves were $136.1m — an exceptional 56% of last year's revenues. The company had total assets of $305.7m, total debt of $72.8m and shareholders' equity of $153.5m. It had a net cash position, which is rare for airlines. The lease-adjusted debt-tocapital ratio was only 41% — similar to Southwest's. All of this puts Allegiant in a strong position to grow the business and weather any setbacks.

Strong profitable growth

Allegiant has grown its capacity at a compound annual growth rate of 89.6% since 2002. In August 2003 it operated just six MD-80s, serving six cities; now the fleet totals 26 MD-80s (as of January 31), serving about 50 cities. Revenue growth has been just as strong, from $22.2m in 2002 to $132.5m in 2006, a

Jan/Feb 2007

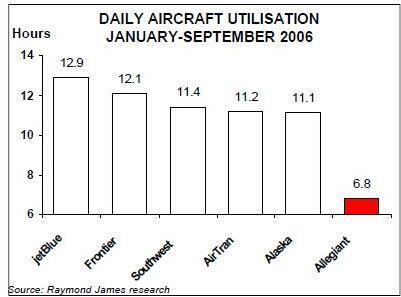

growth in the past 25 years. Orlando is one of America's top family destinations, offering various theme parks and attractions, while Tampa/St.Petersburg is a popular beach vacation destination. The markets targeted by Allegiant are typically too small for non-stop service by legacies or traditional LCCs, which require at least 2-3 daily frequencies, or they are so low-yield that they are not a priority for other carriers. While some of the markets might be suitable for RJs, Allegiant's CASM is significantly lower and its 150-seat aircraft offer a comfortable alternative to the RJs that secondary market travellers are accustomed to flying. Consequently, in roughly 90% of its markets, Allegiant is the only carrier providing nonstop service; of the 70 routes it plans to serve at the end of the current quarter, only six routes have existing or announced service by other airlines. By being the only carrier to offer non-stop service and by making low fares available, Allegiant typically stimulates new traffic and quickly becomes the market share leader for O&D passengers. In other words, the airline has found a profitable niche — something that has historically been a challenge for LCCs. But the "small cities, big destinations" niche is only possible because of a unique fleet and operating strategy. Profitable operation of 150-seat aircraft in the small leisure markets calls for very limited frequencies. Allegiant typically operates only 2-4 flights per week on a route; currently there are no daily flights. This gives Allegiant very low average daily aircraft utilisation — just 6.7 hours in 2006, compared to 11-13 hours typical for LCCs. But the airline compensates for that by buying or leasing used MD-80s at prices that can be 80% below what other LCCs pay for new 150-seaters. The cost of acquiring and introducing to service an MD-80 averages less than $6m for the airline. In other words, Allegiant benefits from extremely low aircraft ownership costs. Fixed costs account for only about half of its total CASM, compared to an industry average of around 70%. The low fixed costs give the airline

Hours

14 12 10 8 6

je tB lu e

DAILY AIRCRAFT UTILISATION JANUARY-SEPTEMBER 2006

12.9 12.1 11.4 11.2 11.1

6.8

Ai rT ra n

Al as ka

Source: Raymond James research

CAGR of 82%. After small operating and net losses in 2002, Allegiant has earned profits in each of the past four years despite the increase in fuel prices. Last year, its operating profit almost tripled to $22.6m, representing 9.3% of revenues, while net profit more than doubled to $15.2m (before a onetime tax accrual of $7.3m). Revenue surged by 84% to $243.3m in 2006. Allegiant's 11.7% operating margin in the fourth quarter was the best among the US legacies and LCCs. According to Merrill Lynch, in terms of pretax margin, Allegiant shared the lead position with Southwest (both 7%). This compared with JetBlue's and US Airways' 4% and breakeven or worse for other airlines.

Unusual niche and MD-80 strategy

Allegiant targets leisure travellers in small under-served cities that otherwise have few options to travel to what the company calls "world class leisure destinations", such as Las Vegas, Orlando and Tampa/St Petersburg (the three currently on the airline's route map). Las Vegas and Orlando are two of the largest and most popular leisure destinations in the US. Las Vegas, where Allegiant is headquartered, offers gaming, shows and other attractions, as well as conventions, and has seen strong and consistent visitor

So ut hw es t

Jan/Feb 2007

Al leg ian t

Fr on tie r

exceptional flexibility — a particularly valuable attribute in an era of volatile fuel prices. First, Allegiant can better tailor flight frequencies to the needs of the market on a daily and seasonal basis. Second, it can more easily enter or exit markets to limit unprofitable flying and maximise profitability. The downside of operating older MD-80s, of course, is that they are very fuel-inefficient and more expensive to maintain. Raymond James’ analysts suggested in a mid-January report that, at current fuel prices, the MD-80 ownership, fuel and maintenance costs largely offset one another. However, they pointed out that Allegiant also successfully employs other aspects of the LCC model, which makes it one of the lowest-cost US airlines. The MD-80 maintenance economics are expected to remain fairly constant. Although the fleet averages 16 years in age (the oldest in the US), it is relatively young in terms of cycles (takeoffs and landings). The fleet averages 25,000 cycles, and no aircraft has flown in excess of 43,000 cycles. With each aircraft adding roughly 1,000 cycles annually, it will be many years before the aircraft reach the 60,000-cycle mark, where maintenance requirements increase sharply due to ageing aircraft airworthiness directives.

Cents per mile

UNIT COST COMPARISONS — 3Q 2006 (Stage length adjusted)

12.8 13.2

12.4 12 10.3 10 8 6 7.6 8.3 8.6 9.0 10.7 11.3

6.9

Source: Raymond James research

Low operating costs

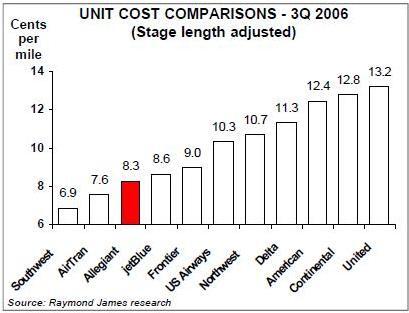

With scheduled service CASM of 7.69 cents in 2006, or 4.15 cents excluding fuel, and an average stage length of 966 miles, Allegiant is clearly one of the industry's lowest-cost producers. In Merrill Lynch's estimates for the first nine months of 2006, Allegiant's CASM (7.73 cents) was 29% below the average legacy CASM (10.91 cents) and 14% below the average for AirTran, Frontier, JetBlue and Southwest (8.96 cents). Excluding fuel, Allegiant's CASM was 46% below the legacies' and 32% below the four LCCs'. Raymond James analysts calculated that, on a stage-length adjusted basis, Allegiant was the third lowest-cost airline in the US in the third quarter of 2006. At 1,000-mile stage length, it had CASM of

8.3 cents, which was higher than Southwest's 6.9 cents and AirTran's 7.6 cents but lower than JetBlue's 8.6 cents and Frontier's 9.0 cents. Allegiant's low cost structure stems from a highly productive workforce, extremely low aircraft ownership costs, a simple product, a cost-driven schedule and low distribution costs. The non-union workforce is among the most productive in the industry, averaging just 37 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) per aircraft, compared to 60-90 at other airlines. The high productivity stems from fleet commonality, fewer unproductive work rules, cost-driven scheduling, automation and the effective use of parttime employees. The cost-driven schedule is an interesting concept. The airline designs its flight schedule so that most aircraft return to the three leisure destinations (effectively bases) at night, thereby reducing maintenance and flight crew overnight costs and providing a "quality of life" benefit to employees. The strategy is possible because leisure travellers tend to be less concerned about departure and arrival times. The "return to base" strategy is even part of the route evaluation process. The two key initial criteria that a prospective new city must meet are that the catchment area population must support at least two

Jan/Feb 2007

D Am elta er Co ican nt in en ta l Un ite d

So ut hw es t Ai rT ra n Al leg ian t je tB lu Fr e on tie US r Ai rw No ays rth we st

weekly flights and that the city is not more than eight hours' roundtrip flight time from the destination. The eight-hour limit permits one flight crew to perform the mission. Having a simple product is critical to keeping costs low. Allegiant does not offer connections, codeshares, FFPs, airport lounges or free catered items. Distribution costs are kept low by not selling through outside channels such as travel web sites or GDSs. All sales are direct through the company, via the website, call centres or airport ticket counters. Internet bookings represent almost 90% of scheduled service sales — the highest among US airlines. Allegiant also benefits from low airport costs. This results from the use of secondary airports at Orlando and Tampa/St. Petersburg, as well as special incentives, such as reduced landing fees and marketing support, provided by small cities eager to attract new air service. lary revenues. First, there are the extra travel-related products that passengers may want to buy: hotels, car rentals, show tickets, night club packages and other attractions. The bulk of Allegiant's ancillary revenues come from the sale of hotel rooms packaged with air travel. The airline has agreements with some 90 hotels in the destination cities and around 28% of its passengers book a hotel room. Second, there are the flight-related items, some of which airlines have always charged for (excess baggage fees, onboard sales of products, etc) and some of which were traditionally included in the air ticket price but are now offered for an additional fee by some airlines. In Allegiant's case, the latter include onboard food and drinks and advance seat assignments ($11 per flight, includes priority boarding). Third, there are the items that one analyst called "nothing more than stealth fare increases", such as checked bag fees ($2) and fees for using Allegiant's website or call centres to buy tickets. The basic idea is to be able to market an attractive low fare and then sell those additional services that each passenger values. In the fourth quarter of 2006, ancillary revenues boosted Allegiant's average scheduled fare of $88 by $19 to $107. The airline plans to grow its ancillary revenues by further unbundling its product and developing new and expanding existing partnerships with hotels, entertainment companies and attraction providers. Allegiant offers a "simple, affordable" scheduled service product, with no requirement for Saturday night stay or round trip purchase. The fare structure consists of six buckets, with prices generally increasing as travel dates get nearer. Prices in the highest bucket are typically less than three times those in the lowest bucket. The highest one-way fare was $239 in December. All fares are nonrefundable but may be changed for a $50 fee. The airline uses yield management to maximise revenues. It continues to pay commission to travel agents for vacation

Diversified revenue strategy

Allegiant's revenue strategy differs from those adopted by other US LCCs. First, its revenue structure is more diversified, with fixed-fee contracts with tour operators and ancillary revenues accounting for as much as 26.7% of total revenues in 2006 (the remaining 73.3% came from scheduled services). Second, Allegiant has taken the so-called "unbundling" strategy, which was pioneered by Ryanair in Europe, the furthest among US airlines. In Gallagher's words, Allegiant is "more than an airline"; it is a "leisure travel company that happens to use aircraft". The fixed-fee contract revenues, though helpful, are basically a relic from the pre-2002 business and are not expected to grow. While scheduled service revenues are the fastest-growing component, ancillary revenues (12.8% of total revenues in 2006) also offer much potential. Ancillary revenues are the highest-margin business; Merrill Lynch estimates that the pretax margin is in excess of 75%. There are basically three types of ancil-

Jan/Feb 2007

packages (but not for flights), because travel agencies tend to have more influence in small cities. Florida destinations. One drawback of the Allegiant model is that it may not be possible to generate much repeat business, which would help facilitate frequency increases. After a weekend in Las Vegas and a vacation in Orlando, the leisure customer will probably want to go somewhere different. However, Allegiant's management feels that Las Vegas demand has not yet peaked, while the Florida market has a different dynamic (many second-home owners and Midwesterners looking for their fun in the sun). Allegiant does not expect to face any near-term gate or facility constraints, though the gate situation at Las Vegas could become a problem in 5-7 years. The consensus opinion is that MD-80 availability is not likely to constrain Allegiant's growth for the foreseeable future. Current availability is good, and the future replacement programmes of airlines such as American, which has over 300 MD-80s, should ensure an adequate supply of highquality MD-80s at favourable prices. However, potential future FAA regulations limiting the age of aircraft in the US could result in Allegiant needing a newer aircraft type sooner than anticipated. Allegiant is expected to continue posting strong earnings growth for the next couple of years. The current consensus forecast for 2007, which the company is comfortable with, is a net profit of $1.20-$1.30 per share, or $25-27m, which would represent a 3546% increase over last year's 89 cents per share (before the one-time charge). Operating margins are expected to rise to the 12-15% range in 2007-2009 (Gallagher said at Raymond James' growth airlines conference in January that Allegiant aims to be the highest-margin carrier in the US). But all of that assumes that Allegiant will be able to replicate the successful Las Vegas formula in the Florida markets. In addition to the market and growth-related risks, the MD-80 strategy and the focus on leisure travellers make Allegiant more vulnerable than other airlines to any future increases in fuel prices or economic slowdown.

Growth plans and prospects

Allegiant anticipates growing its fleet by 5-7 aircraft per year in the next few years. After the exceptional initial four-year growth spurt, ASM growth is expected to slow to the 30%-range in 2007 and average 20% annually over the next five years. The airline has identified "at least 52" more small cities in the US and Canada and "several" popular vacation destinations in the US, Mexico and the Caribbean that it could potentially serve. Analysts have suggested Miami, Cancun and Palm Springs (California) as possible destinations. In addition, the airline expects to increase frequencies in existing markets. The current year's focus will be on developing the markets to Orlando and Tampa/St Petersburg, which were only added in May 2005 and November 2006, respectively, and currently represent 30% of total revenues (Las Vegas accounts for 70%). Orlando was slow to take off, though that was partly because of the difficult 2005 hurricane season. The key challenge — and in many ways a test of the expandability of the business model — is making Florida as successful as Las Vegas. Even though small cities generally may represent a large untapped market for leisure travel, a small city also poses a greater risk that the demand is not there. But Allegiant claims to have a 90% "hit rate" and it quickly pulls out of the 10% of cities that fail to generate "consistent after-tax returns". The flexible business model allows Allegiant to enter and exit new markets quickly and inexpensively — something that will come in handy as the airline will almost certainly face more competition as it grows. This dynamic was seen in January when Allegiant pulled out of Newburgh (New York), which it had served for two years, after both AirTran and JetBlue announced daily nonstop service from Newburgh to Allegiant's

By Heini Nuutinen hnuutinen@nyct.net

Jan/Feb 2007