The future of Alitalia and its domestic competitors: Air One, Meridiana, Eurofly and Blue Panorama

January 2006

Alitalia staggers on, but competition grows

With a successful rights issue and a further round of "state aid", Alitalia’s struggle for survival continues into another year. But — at long last — it appears that the troubled flag carrier is starting to face real competition from Italian–based rivals.

For a while it looked as if the rights issue would fail, as rising fuel prices devastated the original turnaround plan that was put together while Alitalia survived on a €400m emergency bridging loan provided by the Italian government. That loan was allowed by the European Commission only on the condition that privatisation was completed by October 8 last year, but with no possibility of meeting that deadline, the Commission extended it to the end of 2005 — although it warned that if this was not met then it would reopen its enquiry into state aid to Alitalia.

Back in September 2005 both Banca Intesa and Deutsche Bank (the lead underwriters on the rights issue) became concerned about the validity of Alitalia’s existing 2006–2008 turnaround plan (see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2005), since — staggeringly — Alitalia’s management based its forecasts for the entire three year period on an oil price of $40 per barrel.

That was completely unrealistic at the time, let alone now, and rising fuel prices accounted for €100m of the €122m net loss that Alitalia reported for the first half of 2005. In fact Deloitte & Touche, Alitalia’s auditor, initially refused to sign–off the airline’s first half results (only doing so once the recapitalisation plan was confirmed). Unsurprisingly, the two banks urgently requested a revised business plan from Alitalia’s management.

The rehashed "industrial plan" was presented in mid–October, with management calculating that the 40% rise in oil prices would cost the airline an extra €320m in 2006 compared with the forecasts in the previous plan. To make matters worse — and much to the furore of unions — Alitalia had not hedged any of its forward fuel costs.

The airline therefore had to identify at least €150m a year in extra savings over the three–year period — on top of the €400m a year cuts already targeted — if it was to stick to the all–important financial projections that underpinned the rights issue.

To bridge the gap between the original and revised plans, management brought forward many cost–cutting measures. As existing cost–cutting deals agreed by unions earlier in the year had been overshadowed by the increase in fuel costs, the unions agreed to sit down and negotiate with management yet again. Surprisingly, in October new deals were agreed with most pilot, flight attendant and ground staff unions for the introduction of further productivity and efficiency measures within existing contracts, but without further job costs on top of the 3,300 already agreed.

The exception was SULT, a flight attendants union, which called the new industrial plan "economically useless". Alitalia claims these additional measures will save an extra €65m in operating costs a year from 2006 onwards.

Equally as important in meeting the revised savings target was an extra €40m of help given by the government to Alitalia in October via tax breaks, belated compensation for losses arising after September 11 and reduced landing fees to help with rising fuel costs. This was an expensive gesture for the Italian government, because in order to get around the restrictions on state aid it also had to give €80m of similar help to other Italian airlines. Altogether, as part of the updated plan, the airline says it will receive €85m in government aid in 2006, with another €50m in both 2007 and 2008.

The revised plan

The new plan envisages turning Alitalia into a network carrier, which it defines as a "mixed operation of short/medium and long–haul routes, on a lower industrial scale than global carriers". Key targets include:

- Increasing aircraft utilisation by 10% by 2008

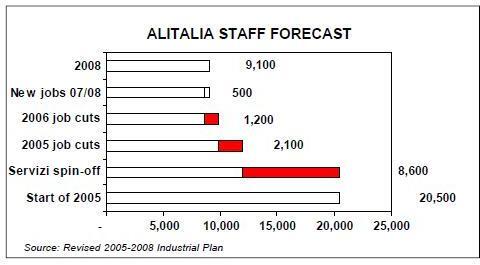

- Reducing staff from 20,500 in 2004 to 9,100 in 2008 (see chart, below).

- Reducing unit costs by 24% by 2008

- Increasing productivity by 41% Essentially the turnaround strategy is dependent almost entirely on cost–cutting and productivity improvement (rather than revenue growth, although Alitalia factors in some capacity growth from 2007, almost all of that on long–haul).

But even if Alitalia can deliver on its promised cost and productivity improvements -and that is a very big if — some of the other assumptions underlying the new industrial plan look distinctly ambitious, particularly Alitalia’s plans for the domestic market. Over the three–year period to 2008, the new plan forecasts improvements on Alitalia’s domestic services of 6.9% in load factor, 4% in unit revenue and — most surprisingly of all — 0.5% in yield. Currently, short- and medium–haul–haul accounts for 74% of Alitalia’s revenue, but this is under tremendous margin pressure from competitors, both domestic and foreign. Yet Alitalia wants to "regain domestic market share" and win more higher margin business travellers through a greater presence at the high–yield markets to/from Rome and Milan, while at the same time developing point–to point domestic markets through new Italian bases.

That’s a stretching target. In the first half of 2005 Alitalia had just a 52% share of the domestic market, and much will depend on Alitalia not only maintaining its position at Milan Malpensa and Rome Fiumicino, but considerably improving it too (hence Alitalia’s bid for Volare — see below — and its consideration of buying 10% of Innsbruckbased Air Alps in December 2005, which operates routes from Bolzano in northern Italy to Rome and Milan Malpensa).

Milan Malpensa and Rome are also crucial to medium–haul as, respectively, 56% and 40% of traffic at these airports connect to/from international flights. Alitalia is looking to capture more east–west Europe traffic flows, particularly in fast–growing eastern European markets. However, in the first half of 2005, despite launching nine new routes to European countries, unit revenues fell by 2.1%. On long–haul Alitalia wants more routes to China and India.

Nevertheless, following the revised industrial plan, Alitalia’s restructuring went ahead as planned. In November Fintecna — the state holding company — paid €92m for 49% of AZ Servizi, the ground services company. Fintecna also controls (but doesn’t own) another 2% of AZ Servizi shares, thus allowing the loss–making subsidiary and its 8,600 employees to be de–consolidated from Alitalia’s accounts.

In December the Italian government reduced its stake from 62.4% to less than 50% after the rights issue raised just over €1bn from both equity and bond holders.

The Italian government bought €489m of the right issue, and institutional investors took up options that the government didn’t exercise. Although this was less than the €1.2bn target envisaged originally, fortunately for the nervous underwriters they did not have to buy any unsold shares, so didn’t face the same situation as happened in 2002, when underwriters for a convertible bond issue for Alitalia (including Merrill Lynch, and Credit Suisse) had to stump up millions of Euros when the issue was not fully subscribed. Once the €27m fees for underwriting and legal costs are taken away, Alitalia raised €979m from the rights issue.

A temporary reprieve?

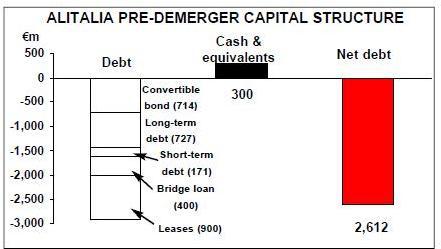

The danger for Alitalia is that although the money raised from the rights issue is supposed to pay for restructuring, it is fast being swallowed up by the need to service debt and by higher fuel costs. Prior to the de–merger, Alitalia group’s net debt stood at €1.7bn as at the end of October, and according to Alitalia’s revised turnaround plan "no financial debt of Alitalia has been passed on to Alitalia Servizi". And to that has to be added €900m of lease obligations, which brings total net debt to a staggering €2.6bn (see chart, above). When set against that, the money raised from the rights issue will not go far. And although the new business plan assumes oil prices of $60 in 2006, $57 in 2007 and $55 in 2008, just how effective Alitalia’s management will be in its new policy of hedging 50% of fuel costs remains to be seen.

Indeed Alitalia’s cash reserves are so low that just two weeks after the recapitalisation, Alitalia could only pay back the €400m bridging loan given to it by German bank Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein in October 2004 (and guaranteed by the Italian government) by borrowing €370m from Francebased General Electric Corporate Banking Europe through the mortgaging of 28 of its aircraft over an eight–year term. That was despite a statement by Roberto Maroni, Italy’s Labour minister, in October that this was the same as "selling the family jewels", and that "if things get worse the government would find itself with an airline that no longer owns its aircraft".

To make matters worse, unions that only a few months ago were asked to make further concessions are now in despair over what they see as continuing management incompetence amid the background of a sluggish Italian economy, which many workers and unions blame on the policies of Silvio Berlusconi’s right–wing government.

General strikes and other protests against proposed budget cuts by the government are likely to intensify as the Italian general election in spring gets closer, but more worryingly for Alitalia, the radical position taken by the SULT union — that the revised Alitalia business plan is unsound and that the airline’s position in the competitive European aviation market is tenuous — is gaining ground among the more moderate unions.

The unions claim that their willingness to sign up to the restructuring deal and accept large job cuts has not been built on, and that management does not appear interested in building up permanently better relations. As a result, Alitalia’s unions proposed a series of strikes in December, although the Italian government imposed a temporary ban to stop these. However, SULT went ahead with a strike on January 19 that caused the cancellation of 74 flights, and this rapidly escalated into a week of supporting wildcat actions from other unions, including pilots and ground staff. The government claimed the strikes cost Alitalia €10m a day, but the unions called off the action after talks with both management and government that may — according to some reports — lead to a delay in the formal acquisition of a majority stake in AZ Servizi by Fintecna from 2007 to 2008.

Against this background, Alitalia is set to release its 2005 financial results shortly.

In the first nine months of 2005 Alitalia reduced its operating loss to €39m, compared with a €620m operating loss in January–September 2004, and its net loss to €119m (€685m in 1Q–3Q 2004). Revenue for 1Q–3Q 2005 rose by 10% to €3.4bn. For the full year an operating loss of around €200m is expected — its seventh consecutive year of operating loss -although unconfirmed reports out of Italy suggest that the airline may be as much as €150m short of its revenue target for 2005, thus leading to a higher than expected operating loss.

Under the revised industrial plan, an operating and net profit is forecast for 2006, although this will be difficult given rising fuel prices and increasing competition from both foreign LCCs and Italian airlines. This latter category includes:

Air One

Air One’s origins date back to an air–taxi company in the early 1980s, but in 1988 Toto — an Italian construction group — bought the company, and in 1995 the airline launched scheduled and charter operations under the Air One brand.

Based in Rome, Air One currently employs 2,100 staff and operates a fleet of 29 leased 737s on a domestic scheduled network covering 23 airports, as well as international charter flights. In Italy Air One operates more than 1,400 flights per week out of two hubs — Rome Fiumicino and Milan Linate — and has an estimated 25% of the domestic market.

In 2004 Air One recorded €490m of revenue and EBIT of €22.4m, but EBIT is forecast to fall to €16.8m in 2005 due to higher fuel costs and increasing competition. Air One carried 5.6m passengers in 2005 and its challenge to Alitalia increased further in January 2006 when the airline placed a firm order for 30 A320s (worth around €1.5bn), with another 60 aircraft on option. The aircraft are scheduled for delivery by 2008, and they will completely replace Air One’s 737 fleet. Just weeks after placing this order, Air One said it planned to convert 10 of the options into firm orders later this year, with these aircraft to be used for the launch of new routes.

Air One is closely aligned with Lufthansa, having signed a commercial alliance in 2000 that includes code–sharing on domestic Italian services and on routes between Italy and Germany. Partnerships are a major part of Air One’s strategy, and in July 2005 it began code–sharing with TAP Air Portugal on Italian and Portuguese domestic routes, as well as on TAP’s services from Lisbon to Rome, Milan Linate and Venice.

In September Air One agreed a code–sharing partnership with US Airways on 13 domestic Italian routes (although this has still to be approved by the DoT); in October code–sharing began with Swiss–based Darwin Airline on Lugano–Rome; and December an interline deal was signed with St. Petersburgbased Pulkovo Airlines. All these are in addition to more than 75 interline agreements, mostly on routes to Rome Carlo Toto, president of Air One, is eager to take on Alitalia in the lucrative northern Italy market, and in November Air One won the Italian CAA contract to operate state–subsidised services from Crotone in Calabria to Rome and Mila Linate — replacing Alitalia on the routes. But a much greater danger to Alitalia would have come from a successful Air One bid for Volare, which Toto wanted to build up as an aggressive competitor to Alitalia.

Meridiana

Launched in 1964 as Alisarda, the Sardinian–based airline expanded onto inter–national routes in 1991, the same year as it adopted the Meridiana name. The airline is controlled by the Aga Khan and (until being overtaken in fleet size by Air One) had traditionally been Alitalia’s main Italian rival. In 2003 the airline attempted to turn itself into a LCC, and initially this was successful. However, after a profit of €0.2m in 2003 Meridiana made a net loss of €13.9m in 2004 after turnover fell 5% to €345m. This led to a major drive to save €150m in costs through 2005, although a plan for 200 job cuts was met by strike threats, and in the end management and unions managed to find the cost savings without the need for redundancies. Nevertheless, through last year speculation grew that the Aga Khan might be willing to sell the airline, either to a management buy–in by ex–Meridiana executives and funded by private equity, or to a trade buyer such as Air One.

Merger talks had previously been held with Alitalia through most of 2003, with the flag carrier reportedly ready to buy an 80% stake for more than €120m, but they came to nothing, as did the rumours of an exit by the Aga Khan in 2005.

Instead, under Gianni Rossi, who became CEO in June 2005 (he was previously CFO of Meridiana until 2000), the airline is attempting a turnaround. Today, Meridiana operates a fleet of four A319s, nine MD–82s and eight MD–83s to 14 domestic destinations, as well as on international routes to Barcelona, Madrid, London Gatwick, Paris and Amsterdam.

However, other than the A319s (which replaced BAe 146s in 2004), the fleet is relatively old, and the airline is examining replacement candidates for the MD–80s at the moment. Rossi has expressed a preference for Airbus aircraft, and an order is expected shortly for aircraft to be delivered over the period 2006–2010.

How these aircraft will be funded is not yet apparent, and Meridiana will need to find several hundred millions of Euros. Revenue of €388m is expected in 2005, based on an 11% rise in passengers carried, to 4m, but indications are that the airline is unlikely to return to a net profit. Load factor last year was just 65.2%, and Meridiana hopes to improve this though more direct sales (currently 17% of revenue comes from the airline’s call centre and 23% from its web site).

Also key to Rossi’s strategy is more airline partnerships, and it has already linked up with Eurofly to bid for Volare (see below). Separate to this, the two airlines have agreed a whole raft of co–operation measures, including maintenance, an interline agreement and the joint development of routes to international markets. Whether this leads to merger remains to be seen, but without a substantial injection of capital it’s unlikely that Meridiana will retain its independence in the long–term.

Eurofly

On long–haul, Alitalia faces its biggest challenge from Milan–based Eurofly, which was launched by Alitalia (initially with just a 45% stake) and other investors in 1989, before becoming the flag carrier’s official charter subsidiary in 2000. However, in 2003, as part of one of its frequent recovery plans, Alitalia sold an 80% stake in Eurofly for €10.8m to Luxembourg–based private equity fund Spinnaker Luxembourg (60% of which is controlled by Italian investment bank Banco Profilo). Spinnaker acquired the rest of the shares the following year.

Eurofly’s management has subsequently diversified away from the competitive short–haul charter market and built up a network of scheduled, seasonal long–haul routes.

Currently, Eurofly operates a leased fleet of eight A320s and three A330s on routes to Cancun, Colombo, Male (Maldives), Fuerteventura, Tenerife, Mombasa, New York JFK, Punta Cana (Dominican Republic) and Sharm El Sheikh.

Also part of Eurofly’s strategy is to the development of point–to–point routes from airports other than Rome Fiumicino and Milan Malpensa — the two main international hubs for Alitalia. Routes to New York out of Naples, Palermo and Bologna were launched in the summer of 2005, and new "non–Milan" routes are under consideration to North and South America (with a three–times- a–week Rome–New York route scheduled to start in May).

Worryingly for Alitalia, Eurofly also has ambitions in the business market, and last year launched an all–business charter service on the routes between New York and Bologna, Naples and Palermo using an A319LR corporate jet with a 48- seat configuration. The service is being extended to Milan Linate–New York from February 2006.

Eurofly carried 1.47m passengers in 2004, 51% up on 2003, and in January- September 2005 revenue rose 16% compared with 1Q–3Q 2004, to €228m, and EDITDAR rose 14%, to €26.3m. However, pre–tax profits fell 38%, to €4.4m, and for full 2005 the airline expects to report a net loss, compared with a €6.8m net profit in 2004, thank mainly to the effects of the Asian tsunami (which cost the airline €15m in lost revenue, according to Augusto Angioletti, Eurofly CEO), the terrorist attacks in Egypt and the loss of tax benefits enjoyed in the 2004 financial year due to the previous year’s losses.

However, net profitability is expected to return in 2006, and Eurofly’s ambitions have been strengthened by a successful float on the Milan stock exchange in December 2005, when the airline listed 48.6% of share capital and raised more than €40m from Italian and foreign investors (such as JP Morgan Asset Management, which bought a 5.2% stake). The float was more than two times oversubscribed, although the share price was hovering just below its issue price of €6.4 as at the end of January.

The proceeds are being used to strengthen Eurofly’s balance sheet, enabling it to obtain better lease terms and/or financing for fleet purchases. In January Eurofly ordered three A350–800s at a cost of approximately €290m (with options for another three), for delivery in 2013 and 2014. And two more A330–200s will be leased in late 2006 and early 2007, to be used for the launch of new long–haul routes.

The float also positions Eurofly better for a strategic acquisition or merger. Volare tried to buy Eurofly from Alitalia in late 2002 — unsuccessfully — but a more likely candidate for an equity partnership may be Meridiana.

In December 2005 Eurofly joined forces with Meridiana to bid for the assets of Volare, which if successful would have seen Eurofly offer short–haul and Meridiana long–haul services under the Volare brand.

Blue Panorama Airlines

Rome–based Blue Panorama was launched in 1998 by tour operator Astra Travel and today operates a fleet of 10 Boeing aircraft on long–haul scheduled and charter routes around the world, with scheduled services to Thailand, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Sri Lanka accounting for approximately two–thirds of all operations.

Its strategy is to operate as a low–fare, niche carrier connecting northern Italy with long–haul destinations, and although initially the airline leased aircraft from Swedishbased Indigo Aviation, it now wants to build up an owned fleet as it develops its network.

Last year Blue Panorama ordered four 787s (with two further aircraft on option), at a list price of €420m, for delivery from February 2009 onwards and to replace the airline’s four 767–300ERs. Two 757–200s were delivered in the summer of 2005 and are used on routes launched in April to Mombassa and Zanzibar, both out of Bologna.

Services from Rome to Frankfurt and from Milan to Kiev were launched in June 2005, but in August 2005 Blue Panorama withdrew its route between Venice and Shanghai after commencing legal action against SAVE, the airport operator, for alleged breach of contract. In January 2005 Blue Panorama had taken over slots previously operated by Volare, but claims that SAVE refused to continue covering certain costs on the route, as it had done previously with Volare and allegedly promised to keep doing in a new contract with Blue Panorama.

SAVE counter claims that it would cover these costs only of Blue Panorama agreed a code–share deal with a Chinese airline, which it failed to do. Blue Panorama is now analysing the setting up of a route to Shanghai from another north Italian airport such as Verona.In November 2005 the airline launched a low cost operation called Blue–express with an investment of €12m and a fleet of two 737–400s borrowed from its parent. These aircraft will be returned to Blue Panorama in the summer of 2006 and be replaced by three 737–300s. Blue–express operated initially from Rome Fiumicino to Milan Malpensa and Bari, but has since expanded onto international routes, to Nice, Grenoble, Munich, and Vienna. With further services to Spain and France planned, Blue–express aims to carry 800,000 passengers in its first year of operation.

Blue Panorama’s revenue for 2005 is expected to be approximately €170m (compared with €130m in 2004), with a forecast rise of almost 40% in 2006, to €235m. The airline is believed to have broken even at the operating level in 2004, although this may not be the case in 2005 following the launch of the new routes and the impact of the tsunami on routes to Asia–Pacific earlier in the year.

In November Franco Pecci, president of Blue Panorama (and the major shareholder in Astra/Blue Panorama), said the airline was looking for external funds in order to extend its operations, although whether this will take the form of a listing, which was tentatively proposed in January 2005 in order to raise up to €100m, remains to be seen. More likely is the purchase of up to 20% of the airline by a private equity fund, it is believed.

Volare

The fiasco of Volare appears to be never–ending.

At long last, the Italian ministry of industry was scheduled to announce on February 1st which of the five bids for the assets of troubled LCC group Volare had been accepted by the airline’s administrator. Volare went bankrupt back in November 2004, with debts of up to €500m, and the airline’s administrator has unearthed further financial problems since.

A slimmed–down and less no–frills version (offering so–called "medium tariffs") of the airline — with just five leased aircraft — has continued to operate a handful of routes between Milan Linate/Malpensa and four regional airports in the south of Italy, mainly in order to hold on to valuable slots at the Milan airports. Turnover in 2005 is expected to be in the region of €75m, with the airline reporting a net loss.

However, of the 700 employees that remain, up to half are covered by the Italian government’s temporary lay–off scheme, called CIG, under which they remain employees of the affected company but have a reduced salary paid for by the government fund.

The delay in decision–making until February 1st was caused partly by a legal appeal by Air One against an earlier decision to allow Alitalia to make a bid for Volare.

Air One’s petition was rejected by an Italian court in mid–January on the grounds that as Alitalia was not insolvent, it could bid for Volare if it wished to — but Air One continued its fight, and on January 30th a Rome court declared that as Alitalia had previously received state aid it could not bid for Volare. That decision — which naturally Alitalia is urgently appealing — forced the Italian ministry to suspend the sale of Volare in farcical circumstances just a few hours before February 1st.

Alitalia made the highest bid for Volare, offering €38m compared with a reported bid of €29m from Air One and €20m from Meridiana/Eurofly. Therefore if the Italian courts eventually do allow Alitalia to bid (and that’s another a big if), Volare will be handed over to the flag carrier. However, this would be an immensely controversial move, and could lead potentially to antitrust investigations in Italy and/or Brussels. Air One argues that if Alitalia does take over the LCC then it will stifle competition domestically, claiming that, for example, Alitalia’s share of slots at Milan Linate will rise from 46% to 55% if it is allowed to buy Volare.

Alitalia states it wants to increase Volare’s fleet by 10 aircraft, but Air One is sceptical that Alitalia will even keep its promise to hire the remaining 700 Volare staff given that the flag carrier is making large job cuts of its own. Unions too are fearful about Alitalia’s involvement given its past history — in 2004 it acquired collapsed regional carrier Gandalf Airlines (against competition from Air One) in order to acquire its slots, and unions believe it never had any intention of saving the airline.

As well as Alitalia and Air One, the other bidders were Meridiana and Eurofly (in a combined bid), Catania–based Wind Jet and the Radici family (who were involved in the launch of Air Europe, a Volare subsidiary).

The future for Alitalia

If some of these companies merge then Alitalia may start to face a real challenge from an Italian rival. And even if this doesn’t happen, the threat from foreign LCCs is increasing all the time. Ryanair already has bases at Milan Bergamo, Rome Ciampino and Pisa, and in March easyJet is opening a base at Milan Malpensa, initially stationing three A319s there in order to serve routes to Athens, London Gatwick, Madrid, Malaga and Paris CDG. easyJet also operates services between Milan Linate and London Gatwick and Paris Orly, and expects to carry 1.2m passengers out of Milan in the year after its base opens there. Italy is easyJet’s fastest growing market and Ray Webster, easyJet’s CEO until the end of last year, called Alitalia "one of Europe’s most inefficient airlines".

The apparent breathing space that Alitalia has from the rights issue is misleading. Although new shareholders such as Londonbased Walter Capital Management (which acquired an 8% stake), UK–based Newton Investment Management (with 4%) and Norges Bank (with 2%) have emerged, this may be more of a short- and medium–term speculative play rather than a genuine belief that a long–term turnaround is possible.

One problem that Alitalia has not addressed yet is its ageing fleet. Around 40% of Alitalia’s fleet has an average age of 20 years and the airline will have to find millions of Euros from somewhere to pay for replacements, let alone the rise in the long–haul fleet (from 23 to 30 aircraft by 2008) forecast in the revised industrial plan. In the last 10 years Alitalia’s management has somehow used more than €4.5bn of new equity and state aid, and the government cannot bail them out again. Indeed there is a point of view that Berlusconi’s government only put money into Alitalia this time around in order to stave off its collapse prior to the elections due on April 9th (and according to opinion polls in early February, Berlusconi is trailing behind the opposition). Giancarlo Cimoli, Alitalia’s chairman and CEO, says that the next logical step is for the government to reduce its stake to below 30% sometime this year, although the government has announced nothing. Ominously for Alitalia, at the end of January Berlusconi’s cabinet broke rank when Roberto Calderoni, Reforms minister, said it would be better if the airline was allowed to go bankrupt.

Cimoli also says "we cannot remain on our own…and need to look at an alliance", and indeed the only hope for Alitalia’s survival in the medium- and long–term is a merger.

But Alitalia’s merger/alliance options are limited, if not non–existent. Before Christmas, some analysts suggested that a slump in Alitalia’s share price might lead to a bid from Air France/KLM, Lufthansa or even British Airways. The last two of these are highly unlikely candidates, but recurring speculation that Alitalia was close to a merger with Air France led to a 20% rise in the share price (to €1.1) in the first few days of 2006. However, Jean–Cyril Spinetta, chief executive of Air France–KLM, quickly denied that talks were taking place — which sent the shares downwards again.

The speculation seems to have arisen from Air France–KLM’s participation in the rights issue, investing €20m to maintain its 2% stake that it has held since a cross–holding deal between Air France and Alitalia in 2002. A merger has always been somewhere on the agenda, but Alitalia is not in any fit state to merge with Air France/KLM, nor any other major airline. In any case, the KLM part of Air France/KLM is likely to resist a merger given its failed and acrimonious partnership with Alitalia in 2000. Alitalia’s so–called White Knight is likely to remain as illusory as the hope that Alitalia can somehow survive in a fiercely competitive European aviation market.

| Fleet (orders) | Alitalia | Air One | Meridiana | eurofly | Blue Panorama |

| A319 | 12 | 4 | |||

| A320 | 11 | -30 | 8 | ||

| A320 | (30) | 8 | |||

| A321 | 23 | ||||

| A330 | 3 (2) | ||||

| A350 | (3) | ||||

| 737-200 | 3 | ||||

| 737-300 | 6 | ||||

| 737-400 | 20 | 4 | |||

| 747-200F | 1 | ||||

| 757-200 | 2 | ||||

| 767-300ER | 13 | 4 | |||

| 777-200ER | 10 | ||||

| 787 | (4) | ||||

| MD-11 | 5 | ||||

| MD-80 | 71 | 17 | |||

| Total | 146 | 29 (30) | 21 | 11 (5) | 10 (4) |