Charter airline legacy: the case of MyTravel

January 2004

It has been a disastrous 12 months for MyTravel Group, the UK air–inclusive tour (AIT) operator that includes MyTravel Airways and MyTravelLite.

Is the company’s performance due to poor management, or does its troubles have wider implications — such as the beginning of the end for the traditional package product, and hence the charter airline?

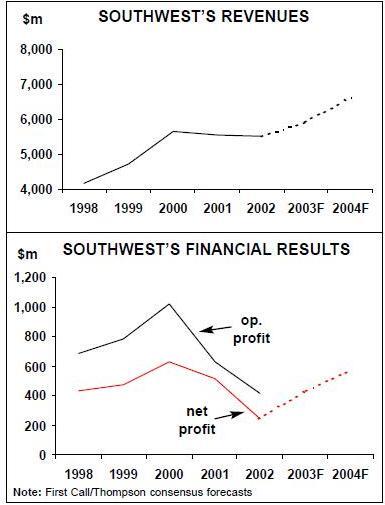

The decline of MyTravel — previously known as Airtours — has been steep. Up until 2000 the group was successful, or at least as successful as you can be in the wafer–thin margin world of AIT. And then came September 11, which had a devastating effect on financial results (see graph, opposite).

For an analysis of MyTravel’s historical performance and the effects of September 11, see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2002.

Yet instead of 2001 and 2002 being a messy but temporary blip on profits, this was followed by a even worse 2003, in which the Group declared a £913m ($1.5bn) net loss for the year ending 30 September, compared with a £60m ($93m) loss in 2001/02.

Of that loss, £472m was exceptional, £359m of which was for a write–down of assets and goodwill. Most of this was a legacy of MyTravel’s troubled expansion policy, designed to make it a truly vertical AIT group by owning every part of the value chain.

The write–downs included £68m for German operations, £35m for hotel assets and £71m for US businesses. But that still leaves £441m of underlying net loss, largely driven by an operating loss before goodwill and exceptionals of £358m (compared with a £20m operating loss in 2001/02).

According to Peter McHugh, chief executive at MyTravel Group, these results were due not only to "legacy and one–off issues" but also to what he calls Group "structural issues … and poor management information systems" — matters that MyTravel claims are now being addressed. Looking at external factors, the Group was hit by the effects of the Gulf War, the SARs epidemic as well as "unusually hot weather in the UK and Scandinavia", which reduced the number of people taking package holidays abroad.

Clearly, the same external factors affected all AIT operators in the UK, yet none of them managed to rack up the substantial underlying operating losses that MyTravel did.

In contrast, in the year ending 31 October 2003 First Choice (which includes First Choice Airways, previously known as Air 2000) reported a net profit of £32m, compared with a £26m profit in 2001/02, based on an operating profit before goodwill and exceptionals of £89m ($151m), compared with a £72m profit in 2001/02.

Internal woes

With rivals doing well in the same difficult circumstances, the underlying reason for MyTravel’s poor performance lies elsewhere, for instance, in poor management, including a lack of adequate information systems, an absence of effective cost control and the decision to deeply discount holiday prices in 2003.

But perhaps MyTravel’s troubles really started a few years ago, with the attempt to construct a global travel company (reminiscent of SAS’s "Total Travel Concept").

The exotic mix of companies that the group bought — such as a foreign currency provider, a car hire firm, a hotel room distributor, a US cruise company, a vacation resort and assorted non–UK tour operators — were difficult to control and impossible to gain meaningful synergies from. In the last financial year, the disposal of what are now deemed "non–core" assets has earned the group a handful of working capital at the cost of horrendous write–downs and the waste of thousands of hours' worth of management time.

MyTravel claims that if it had been allowed to buy the company it really wanted to acquire — First Choice, in 1999 — then its strategy would have proved successful after all.

Maybe so, but there is a nagging feeling that even if the European Commission (EC) had not blocked the Airtours/MyTravel takeover of First Choice on competition grounds, then the "quality" of MyTravel’s management would have adversely affected the performance of the combined MyTravel/First Choice anyway.

But the argument is academic, and all that is left is MyTravel’s ongoing pursuit of a damages case against the EC over the ruling.

In 2002, the European Court of First Instance ruled that the EC’s decision was wrong, and so MyTravel is seeking more than £0.5bn in damages on the grounds that a combined group would have weathered the changes in the AIT market much better. Inevitably, the case will take years to resolve, by which time MyTravel may not be around to enjoy the fruits of a largely meaningless legal victory.

Also contributory to MyTravel’s woes is the ongoing managerial merry–go–round at the group. Ever since founder and former chairman David Crossland resigned in February 2003, claiming that the company "was in excellent hands", senior management has been a shambles (although MyTravel’s troubles started well before Crossland left).

For example, MyTravel has had four group finance directors in two years, the latest being John Allkins, formerly CFO at technology company Equant, who replaced Kazia Kantor after she resigned in August 2003. The latest reshuffle among senior management was in December 2003 when Duncan Wilson, head of the Group’s UK and Ireland operations, resigned and was replaced by Group COO Philip Jansen. Until there is a settled, competent management team, the group will find it hard to recover.

Belatedly, MyTravel has recognised its mistakes, says it will not discount in the 2004 season, and after a change in "internal processes" is forecasting it will return to profit in 2005. In addition, the Group completed a major refinancing in 2003, agreeing a three–year extension on repayment of £221m of bonds to 2007 — although MyTravel paid a heavy price, with the bond interest rate rising from 5.75% to 7% and bondholders being granted shares and warrants giving them a 21% equity share.

In a presentation made to UK analysts in December 2003, chief executive Peter McHugh said: "In the short to medium term, the Group’s earnings and cash flows will remain subject to significant risk due to the high fixed cost structure and high levels of indebtedness and we will have to continue to manage our resources carefully."

Those words are hardly going to reassure long–suffering shareholders at My Travel Group, who have seen the share price plunge from £5.45 to less than 10p in less than five years. (At the start of January trading, the share price was around 11p.)

Industry implications

While it is easy to place a large part of the blame for MyTravel’s demise on its management and strategy, the rationale behind some of MyTravel’s poor decisions needs to be examined — and it is this analysis that is worrying for the AIT industry, and hence for charter airlines as well.

A key problem with MyTravel is that is has relied on the traditional AIT business model for too long — a model that relies on large amounts of low–margin packages being sold to "mass–market" customers that fly to traditional Mediterranean resorts for one or two–weeks, departing from/returning to a major UK airport in the middle of the night. But as Aviation Strategy has pointed out before (see July/August 2002 issue), this legacy model is coming under attack from the fact that traditional AIT customers are migrating to self–assembled, more flexible holidays.

The relentless march of customers towards flexibility is against everything ingrained into the mindset of the northern- European based AIT giants, and many executives ignored the trend for far too long. When they did respond, it was by the disastrous policy of discounting packages in the belief that customers would come flocking back to the traditional package product, now made even cheaper. Well they didn’t, and by cutting prices on holidays that would have been sold to "hard–core" package holidaymakers anyway, many AIT operators plunged themselves into the red (don’t forget that AIT operators have smaller margins than even the airline industry).

At this point many AIT operators realised that something had to be done about the trend for flexibility, and the most obvious answer was to provide seat–only sales on their own charter airlines. But again this was (and is) a flawed strategy, because customers still associate charter airlines with a poor product — i.e. flights that depart and return late at night or very early in the morning, often prone to severe delay, and which only fit in with seven or 14–day itineraries.

This product looks even poorer when compared with the offer of the low cost carriers (LCCs). What the LCCs and their simple websites have done is to make consumers realise that organising flights is an easy, quick process that does not need the skills of a travel agent. Many consumers have therefore leapt from booking an all–inclusive package straight to an LCC website without the intermediary step of visiting the seat–only operation of an AIT. And the competition from LCCs is increasing further now that the overlap between the destinations of the LCCs and the charter airlines is growing.

For some AIT companies, the fierce competition from LCCs to their seat–only operations and the stagnation in demand for the package holiday product has meant a radical change in strategy. First Choice, for example, has recognised that the AIT market has changed fundamentally and irrevocably, and now offers more and more specialist, "higher value" holidays, where prices (and margins) are higher than the standard package holiday and certainly do not need to be discounted — what some analysts call the "Kuoni" strategy.

As many of the niche destinations served by specialist holidays tend to be long–haul, this has the added bonus of facing less competition from the LCCs, and hence less possibility for customers to assemble their own packages.

Other, smaller AIT operators are taking the first tentative steps to producing brochures with separate accommodation and flight prices, allowing customers to mix–and–match as required. But MyTravel Group refuses to accept this analysis of the market, and insist that the mass–market package product can be profitable again.

However, MyTravel’s new management has now accepted that discounting is not a sensible idea. Even in the summer of 2003, it resorted to deep discounting at peak periods: MyTravel cut prices so much that for each holiday MyTravel sold, it lost around £25–30 — and it sells around 6m holidays a year. It is turning instead to cost cutting. Fixed costs typically account for a third to a half of an AIT operator’s costs — and perhaps there is no greater fixed cost than a charter airline.

MyTravel's airlines

MyTravel’s UK charter airline — My Travel Airways — has suffered from the troubles at its parent group. Mike Lee, MyTravel aviation chief executive, left in March 2003 after being in charge of all airline matters since 1997, and in the same month Travel Trade Gazette reported that MyTravel cancelled summer contracts with charter airlines such as Monarch, Spanair, Futura and Iberworld for between 200,000 and 350,000 seats — up to 10% of the group’s total airlift capacity, though yet again MyTravel appeared to be playing catch–up as rivals such as TUI and First Choice had already cut flight capacity for the 2003 summer season back in late 2002.Soon after these moves, in June 2003, instead of receiving four A321–200s direct from Airbus as planned, the MyTravel Group agreed a sale and leaseback deal with debis AirFinance. MyTravel sold the aircraft to the lessor and agreed six–year operating leases for the aircraft, one of which is for MyTravel Airways and three for MyTravel Denmark.

And in August 2003, MyTravel announced it was retiring three DC10–10s in order to trim capacity, though a DC10–30 will remain.

Along with continuing efforts to increase aircraft utilisation, it is clear that that MyTravel Airways is coming under considerable pressure from Group management to cut costs.

As for MyTravel’s LCC, its future appears to be in doubt. MyTravelLite was launched in October 2002 and operates from Birmingham and Manchester to Belfast, Knock, Dublin, Faro, Malaga, Almeira, Murcia, Alicante, Palma and Barcelona with a fleet of four A320–200s. A twice–daily Dublin route was also started in September 2003 as a direct challenge to Ryanair and Aer Lingus.

However, reports out of London in December 2003 suggest that MyTravel Group was "evaluating options" for the LCC, including a reduction in the fleet and route network (routes out of Manchester are believed to be most at risk). This is part of the Group review of costs, but also may reflect a strategic reappraisal of how beneficial an in–house LCC truly is. Peter McHugh, MyTravel Group chief executive, is reported as saying that: "We are not abandoning the brand, we will use it as a flight–only holiday product rather than as a stand–alone scheduled airline."

But even if the LCC is abandoned, MyTravel Group still appears to be clinging to the traditional charter airline for its airlift needs — even though other parts of the industry are now moving away from the charter model.

A charter future?

The charter airline has long been the unfashionable part of the European aviation industry, partly because the charter carriers have always depended on the strategies and fortunes of their parent AIT operators (large, independent charter airlines have largely disappeared over the last 10 years, with the exception of Monarch). And it is this precarious dependence of the charters on the AIT companies that may well, at last, spell the end of the charter industry.

As the AIT firms beefed up their seat–only operations as a response to consumers' increasing demand for flexibility, some people believed there would be resurgence in charter airlines. As pointed out previously, this just didn’t happen — and that was largely down to the LCCs.

The success of the LCCs in drawing off previous package holiday customers, combined with the need to cut costs at the AIT groups, has led to a Damascus–like conversion to the LCC model at some AIT group in the last few years — and this is a trend that is still continuing.

For example, German AIT giant TUI launched its own LCC — Hapag Lloyd Express — in December 2002 (ironically not long after the German group criticised MyTravel for doing exactly the same with the launch of MyTravelLite).

This LCC has apparently been so successful (although it is not yet profitable) that TUI now want to shift short–haul flights from its standard charter airline Hapag–Lloyd to Hapag–Lloyd Express, and it is also trying to introduce as many LCC practices as possible into the "full–cost" Hapag Lloyd. In addition, TUI is believed to be planning the launch of a LCC in the UK in 2004.

So does this signal the end of the charter airline? In one sense the trend of AIT operators to launch LCCs is a red herring, since AIT groups need to reduce costs anyway in order to underpin thin margins. If a new or existing "in–house" airline serves AIT customers — whether or not it adopts LCC practices — it is still a charter carrier.Many people disagree with this. TUI, for example, now seems almost fanatical in its espousal of the LCC concept at the expense of the charter model. In October 2003 Wolfgang Kurth, CEO of Hapag–Lloyd Express, claimed that all "fully–fledged" charter airlines would be gone by 2006, and that the only charter "survivors" would be airlines that were a hybrid, offering not only flights aimed at AIT customers but also no–frills flights aimed at the non–AIT market. But when is an airline not a charter airline? Surely even if an airline adopts a low cost strategy and serves non–AIT customers, if it still offers flights for the AIT product of parent companies — and hence still needs an ATOL licence — then it is still a charter airline.

IAT and non-IAT together?

But can tour operators' in–house airlines really serve the AIT and non–AIT markets at the same time? They might be able to in the short–term, but surely in the long–term they will lose out to the exclusively "non–AIT" airlines, for two reasons:

- First, can one single airline operation serve both these markets? Can the same airline efficiently offer seven and 14–day products concentrated on the summer months and a 365–day scheduled operation?

- Second, it is becoming increasing apparent that seat–only customers have little loyalty to the AIT brands. If anything, the tour operator brands as applied to airlines are a turn–off to customers looking to book a seat–only product.

This is a point that the AIT giants simply do not recognise, as recently they have been changing the names of charter airlines from stand–alone brands to the brands of the parent AIT groups — often to the bewilderment of consumers. JMC, the 1998 merger of Flying Colours Airlines and Caledonian Airways, was itself renamed Thomas Cook Airlines in April 2003, while Air 2000 rebranded itself as First Choice Airways in October 2003.

Meanwhile TUI Group, which acquired Thomson in 2000, is renaming Britannia Airways as Thomson, but with a TUI logo.

In fact it was Airtours that started the recent rebranding trend, when the group name changed to MyTravel and the Airtours International was rebranded as MyTravel Airways in 2002 — though the wisdom of changing such as a well–known brand as Airtours to the anaemic MyTravel is debatable.

But some AIT companies are thinking further.

Logically, why do the AIT groups have to have their own in–house airlines anyway, whatever they are labelled? Wouldn’t it make sense to completely offload the fixed costs of in–house airlines and at the same time break the link between the accommodation and the lower–margin flights?

It’s happening already — or almost is. One major AIT operator is believed to be planning the scrapping of its existing charter operation, replacing it with a scheduled airline that would serve seat–only customers through an "all destinations all the time" strategy. Crucially, the airline would issue a scheduled ticket and thus no longer need an ATOL licence.

The link between the accommodation and a bundled flight would disappear in the company’s brochures, leaving the group’s airline to independently price and offer its scheduled flights to customers booking group accommodation, but with no obligation on them to book the "in–house" scheduled airline.

| MT Airways | MT Lite | MT A/S* | |

| A320 | 12 (3) | 4 | 3 |

| A321 | 6 (1) | 3 | |

| A330 | 4 | 4 | |

| 757-200 | 4 | ||

| 767-300ER | 3 | ||

| DC10 | 1 | ||

| Total | 30 (4) | 4 | 10 |