United Airlines: the extent of the reorganisational challenge

January 2003

United Airlines operates the world’s strongest airline network. It is the cornerstone of the largest global alliance, has unassailable domestic hubs at Chicago O'Hare and Denver and powerful, protected positions at Tokyo–Narita and London- Heathrow. It has a modern, efficient fleet, and extremely experienced, capable staff.

However, there is a serious chance that United could be forced into liquidation during 2003, and there is open debate about the type of changes needed if United is to successfully reorganise.

To survive, United must rapidly meet three challenges.

• Stabilise DIP financing and cash flow

United’s current debtor–in–possession financing will terminate unless it limits its aggregate cash burn from 7 December to 15 February to $960m. This would require reducing its current daily burn rate, reported to be $17–22m in December, to a level between $6–8m per day in late January and early February. After meeting these short–term covenants, United must make further improvements in order to achieve cash–positive operations

• The initial turnaround

United must implement a 2003–4 business plan that gets reasonably close to P&L break–even on a post reorganisation basis, demonstrating a clear foundation for an eventual profit recovery

• Establish a recapitalisation plan

This must be based on a long–term plan for sustainable profits over a full–business cycle that fully recognises the major competitive changes affecting all traditional Big Hub network carriers, protects the interests of all of the investors and creditors contributing to the reorganisation, and avoids the dysfunctional governance that contributed to United’s financial collapse.

United’s ability to meet these challenges will be limited by the very weak market environment and its dependence on major sacrifice by staff and creditors, who may not share a common understanding of the gravity (or the causes) of the current crisis.

United has very little time for education, discussion or the development of creative alternatives. The US Chapter 11 bankruptcy process is not designed to facilitate radical restructuring, and it is not designed to move quickly unless all stakeholders are largely in agreement. External shocks including war in Iraq or a further US economic downturn could quickly render these issues moot.

Also, one must question whether United’s current management could rapidly execute the biggest turnaround in aviation history.

Most of current management were directly involved in the many decisions that created the current crisis, and have been reluctant to make major changes. Recent business plans did not demonstrate a clear grasp of the magnitude of the challenge, and were openly criticised by Wall Street and the ATSB.

Cash-flow covenants

To meet the phase one DIP loan covenant, United would need to reduce cash burn below current rates by $200–350m prior to 15 February. It is extremely unlikely that any schedule cuts could conserve cash in this time period, as many operating costs cannot be avoided on a few weeks notice. If these covenants are to be met, the entire cash savings would need to cut from immediate reductions in ongoing wages, leases and rents. If 80% of this burden fell on labour, it would require full implementation of wage cuts of 30–40% for every company–employee by 15 January.

Unions would need to approve such cuts without any clear evidence of a long–term profit or reorganisation plan, and without any real opportunity to communicate the issues to their members or to propose alternative solutions.

Getting back to break-even

Getting back to break–even Vaughn Cordle, a senior United pilot who has been publishing expert analysis of United and industry financial issues for several years, estimates that United needs slightly over $3bn in immediate cost cuts just to stabilise its financial situation and to serve as a foundation for an eventual full recovery.

These estimates are double the nominal cost savings proposed in United’s rejected ATSB loan application, and three times greater if foregone pay hikes are included.

A summary of one of Cordle’s scenarios illustrates the magnitude of the short–term cost cutting challenge, (see table below).

Other scenarios involve greater immediate capacity cuts, in recognition of the serious industry overcapacity and the poor contribution levels of much current flying, but these also incur greater transition costs.

Obviously larger wage cuts and productivity improvements would allow more flying to be profitably maintained. But in all cases, first year labour cuts of the order of $2.0–2.5 bn appear critical.

The 2% RASM improvement assumption may be optimistic (United’s RASM fell 4% last year) unless United’s move accelerates the final shakeout of excess Big Hub capacity. It would be absurd to suggest new near term revenue opportunities (such as a rebirth of Shuttle by United) under current market conditions, or until the profitability of United’s core network has clearly recovered. Cordle estimates that over half of the year one labour savings could come from a simple roll back of wage increases granted since 1999, when the original concessions granted to fund the 1994 ESOP expired.

United’s labour costs increased by $1.4bn between 2000–02, with average employee pay increasing 25%. As much as one–third of the savings can come from major work–rule reform (crew scheduling constraints, vacation overrides, outsourcing limitations, etc). Labour savings from capacity cuts and productivity improvements would obviously shift an even greater burden of the pain onto staff that would be laid off, and who would have little prospect of benefiting from an eventual recovery.

Restoring sustainable profits

United’s (and other industry) projections argue that once labour costs are brought back "into line", and the economy works its way out of the current down–cycle, demand growth will return. Restoring the pricing and capacity growth of the mid–90s in these projections also restores the profit margins of the mid–90s, offering the prospect of returns for investors, and eventual wage snap–backs. United’s ATSB loan application was based on 9% annual revenue increases between 2003–05.

These planning approaches assume that nothing happened in recent years to change the fundamental competitive position of United (or the other Big Hub carriers) and ignores the expansion of Southwest and other non–network, low–cost carriers, the collapse of industry pricing structures and the widespread alienation of previously loyal business customers. United’s ATSB revenue projections result in a RASM recovery nearly three times greater than the industry experience in the mid–90s, before Southwest became a major influence on nationwide price levels.The hypothesis here is the Big Hub carriers as a group must shrink by another 10- 15% from current levels, and may eventually need to shrink further if Southwest–type non–network carriers can continue high rates of profitable growth, eroding the maximum Big Hub market share even further. United and the other Big Hub carriers must return to a pre–bubble pricing/revenue environment with lower business fares, and a much smaller gap between business and leisure fares (either its own, or those of the low cost carriers). Lower business fares must be maintained in order to restore business customers' lost faith that the traditional airlines offer value for money, and to block the further loss of share to the low cost non–network sector.

These larger industry capacity and pricing issues were discussed at length in an earlier article ("Is the traditional Big Hub model still viable?", Aviation Strategy, July/August 2002). United’s core network — Chicago, Denver, Narita, the Star Alliance — is very strong, and if United can quickly achieve the magnitude of cost reductions suggested above, it could force other carriers with weaker networks into bigger cutbacks while preserving more employment for its own people. Most competitors are hoping that a United collapse and liquidation will solve the overcapacity and yield problems, while allowing them to avoid the painful decisions United now faces.

One cannot assume any medium–term future increases in real business fares, other than short–term cyclical fluctuations. RASM will improve with general economic recovery and as significantly reduced capacity and simpler prices allow the elimination of the lowest discount levels that not even Southwest can offer profitably. But even if the US economy returns to robust mid–90s economic growth, the potential for steady capacity growth and fare increases is nowhere on the horizon. The old conventional wisdom tightly linking GDP and revenue growth is obsolete. Under optimistic views of economic and industry recovery, RASMs might plateau at roughly 1995–96 levels.

To achieve sustainable profitability, United must implement the $3bn year one cost reduction, and then find $300–500m in annual cost/productivity savings over the following three to five years ($1–1.5bn in all) to reduce CASM to a level where the airline can cover the cost of capital across a full business cycle, build up positive equity and begin to restore its balance sheet. These second phase savings would most likely come from increased technology applications, outsourcing and ongoing product simplification, and opportunities would increase with year one work–rule reform. They would require process re–engineering and investment and could not be realistically included in any year one turn–around projections.

Recapitalisation and new governance

To successfully reorganise, United must establish a new foundation for how investors, employees, current creditors and other stakeholders will be compensated over the course of future business cycles. This could take many different forms including complete employee control and complete creditor control.

The 94 ESOP was designed along the lines of many current plans and proposals, with emphasis on the year one cuts that are a critical first step, but no serious thought about a plan for longer–term profitability, and with willful indifference to the governance process that determines how the risks and rewards of the different investors are balanced.

It is clear that any United survival plan will require unprecedented sacrifices from current staff and creditors. At this point it is totally unclear who might benefit if United successfully reorganises. Despite urgent deadlines, parties may be unwilling to make the necessary investments in (or concessions to) future operations without confidence that the future governance structure will protect them.

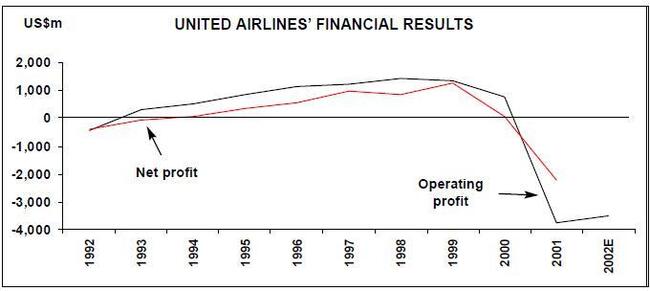

A long, steady path to bankruptcy

United has been in steady decline for decades. At the dawn of deregulation, United was 33% larger than the number two carrier, American, 80% larger than Delta and three times the size of Northwest.

With its size and network strength, United was ideally positioned to become even stronger and more profitable once given full commercial freedom. Its industry leadership position was eclipsed by the early 80s and its profit margins and relative market value declined throughout the 80s and 90s. Prior to September 11, 2001, United’s market capitalisation was only 60% of American’s and only 30% of Southwest’s.

United’s management culture has long been bureaucratic and complacent, confident that the airline’s size created market power that would always generate profits.

Through successive regimes, senior United management also remained highly centralised and hierarchical. This tended to reinforce the internal tendency to focus more on perceived "power" than on the need to provide the greatest customer value and achieve the highest productivity.

It also tended to discourage initiative, innovation, risk–taking, challenges to accepted practices, and open two–way communication.

Financial challenges usually resulted in major transactions — the 1987 Allegis creation and rapid break–up, the 1989 British Airways takeover plan, the 1994 ESOP, the 2000 $4.3bn US Airways merger bid — that would protect incumbent management, while creating enormous long–term risk.

As United management was slow to adapt its thinking to its more volatile, competitive environment, it also failed to communicate the new market realities to its staff.

Instead of realigning costs with either competitive, market levels, or the long–term revenue potential, both unions and management continued to assume that United’s historical market position was their birthright, and focused narrowly on battling over their respective shares. Both internal union dynamics and internal management culture reinforced a highly short–term focused adversarial system, resulting in a long series of highly destructive confrontations including a major 1985 strike, union participation in various takeover bids (including the 1994 ESOP), and the 2000 pilot slowdown, which cost the company nearly $1bn in lost revenue.

Both sides viewed the ESOP through the narrow prism of short–term contract negotiation.v Neither side had any intention of using employee ownership to better align the interests of employees, outside shareholders and other stakeholders. Prior management viewed the ESOP as the means of achieving short–term (five–year) wage concessions to boost the P&L during the industry downturn of the early 90s. Unions viewed the ESOP as the price to be paid to secure long–term advantage in the collective bargaining process. New management actually surrendered its (rarely–used) right to communicate directly and freely with rank–and–file staff and made no further attempts to explain the growing challenges to United’s competitive position and profits, as the current industry crisis unfolded.One of the major reasons United collapsed ahead of other seriously troubled Big Hub airlines is that the new employee–owners massively overpaid for the company, and then failed to make any improvements in governance or labour relations.

The ESOP directly placed a $3bn financial penalty on the company ($2 bn cash out plus $1bn after tax book costs due to negative dilution).

The employees' $5bn investment was worth less than $1bn prior to September 11, 2001, and of course is now worthless. The Board members and senior managers who engineered and implemented the ESOP remain firmly in control of United despite the complete failure to serve the fiduciary interests of the shareholders.

Who can save United?

The logical components of a United turnaround are extremely daunting but they are also quite straightforward. But companies cannot be saved by logic or spreadsheets, human beings must lead the process.

The United turnaround approach outlined here will require extraordinary initiative, the ability to powerfully convince dozens of stakeholders to accept enormous pain, new business plans based on a completely new thinking about United’s competition and customers, and an immediate 180 degree reversal of the labour–management practices of the last three decades. The biggest challenge to United’s survival may not whether it can implement $3bn in cost savings in the next several months, but whether it can totally overcome the problematic history of its management culture and industrial relations in that time.

The SAir precedent

The only real precedent for United’s current situation is the collapse of Swissair’s parent, the SAir Group. Both companies had serious but easily (and widely) understood problems. The core airline networks were fundamentally sound but faced cash crisis driven by external financial burdens (failed conglomerate investments, overpaying for the ESOP). The Board members who were directly responsible for the serious problems wanted desperately to hang on to that control and refused to acknowledge or address the obvious problems. Facing a crisis, the Board brought in an industry outsider, who kept the old management team intact and aggressively pursued taxpayer bailouts.

There is no rational business reason why United cannot be reorganised successfully, but there was also no rational explanation for the liquidation of Swissair. In Zurich, the people who had been part of the past decisions and the old culture were unable to change their behaviour, even as the cash ran out and one of the greatest names in aviation history was shut down.

| US$m | 2002 | 2003 | Change | |

| Op Revenue | 14,248 | 13,622 | (626) | |

| Labour Expense | 6,940 | 4,858 | ||

| Rent/ | 1,804 | 1,237 | ||

| Depreciation | ||||

| Other non-labour | 7,943 | |||

| Total Op Expense | 16,687 | |||

| Operating Profit | (2,439) | |||

| Operating Margin | (17%) |