Southwest: how to overcome the September 11 crisis

January 2002

Having again proved its remarkable resilience when the going gets tough,

Southwest is now the first US major airline to start cautiously growing again. Early next month (February), it will take delivery of two 737–700s — its first fleet additions since September 11 — to boost service in selected major Northeast–to–Florida markets.

This is several months earlier than expected. Previously Southwest did not envisage needing more aircraft until April, at the very earliest. When announcing the decision just before Christmas, the airline said it was still in a recovery mode, with load factors lagging year–earlier levels, but that performance had been strong enough to justify adding some new flights (but no new cities at this stage).

In recent weeks there has been a growing perception that the recovery prospects for the airline sector are brightening.

This partly reflects improved outlook for the US economy — recession is almost over as GDP growth is expected to resume in the current quarter — and a slow but steady improvement in industry fundamentals. However, most airlines face a long road to financial recovery and have to continue to focus on cash conservation and cost cutting before they can think about expansion.

Southwest’s ability to resume growth so early indicates that its unique way of handling the crisis has worked. When all the other major airlines slashed capacity by 15- 20% and laid off 10–15% of their workers in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, Southwest merely froze its headcount and temporarily suspended growth plans.

Some people called that strategy risky, but Southwest made it clear that it was ready to reduce its schedule at a moment’s notice if load factors remained weak. The high percentage of owned aircraft in its fleet (about 70%) would have given it much flexibility to cut capacity quickly if necessary.

Also, Southwest was quick to implement extensive cash conservation measures, including cutting nonessential operating expenses, delaying nonessential capital spending and deferring aircraft deliveries.

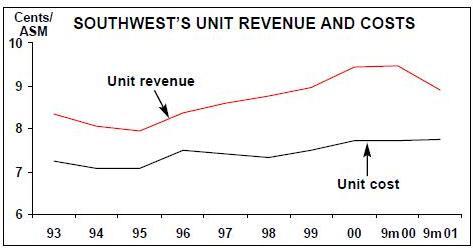

But, above all, Southwest has been able to get away with it because of its hugely successful low fare strategy and extremely low cost structure. With costs per ASM of 7.73 cents in 2000 and 7.66 cents in the first nine months of 2001, the unit cost advantage over competitors appears to have widened over the past couple of years.

The industry’s fourth–quarter operating statistics provide further evidence that Southwest’s post–attack strategy has worked. Its capacity (ASMs) rose by 6.4% year–over–year in October–December, compared to an aggregate 14.6% decline for the major carriers. However, Southwest’s traffic (RPMs) fell by only 0.5%, compared to a 19.6% fall in industry traffic. This meant that Southwest’s load factor decline of 4.5 points was only marginally higher than the industry’s 4.1–point decline.

For the year, Southwest still managed 9% capacity growth — within the 8–10% benchmark range that it uses for planning purposes though less than the previous year’s 13% — while industry capacity declined by 3.4%. Southwest’s traffic rose by 5.4%, while its load factor declined by 2.4 points to 68.1% in 2001.

However, much of the traffic has been generated by fare sales. Yields and unit revenues have been hit hard because, like all US airlines since September 11, Southwest has discounted aggressively to attract passengers.

Southwest executives said in November that the airline had been able to maintain high aircraft utilisation and its trademark quick turnaround times, despite increased security measures. The biggest operational issue had been passenger processing, which was a huge problem at some cities at peak times.

Market share gains

Although this was probably not the intention, Southwest was poised to gain market share simply by the virtue of maintaining pre–attack service levels in most markets when competitors cut planned capacity by 15- 20%.

In a recent report, Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg provided a rather dramatic example of how that process was playing out in the important Phoenix–Los Angeles market. Between September 1 and November 1, total service in that market declined from 44 to 33 daily flights, as both American and United pulled out (with regional partner SkyWest replacing some of United’s capacity with RJ service) and America West cut its flights from 15 to eight.

By simply maintaining its 19 daily flights, Southwest saw its seat share increase from 44.6% to 63.5% — almost 20 percentage points.

Linenberg suggested that, given Southwest’s commanding position in the Phoenix–Los Angeles market, its revenue share had probably increased at a disproportionately greater rate. He predicted that Southwest would repeat that scenario in many other markets, including Baltimore/Washington, Raleigh/Durham and Las Vegas.

In particular, Southwest is poised to benefit from the decisions of three major network carriers to drastically scale back or eliminate their low cost, low fare subsidiaries. United discontinued the United Shuttle brand at the end of October and US Airways eliminated MetroJet in December, while Delta has halved its Delta Express operation. The modest service increases that Southwest is implementing next month are all in former MetroJet and Delta Express markets out of Baltimore and Islip (Long Island).

Aircraft deferrals

In the wake of the September 11 events, Southwest was the first airline to complete negotiations with Boeing to defer aircraft deliveries, reflecting its considerable clout with the manufacturer. The airline deferred 19 737–700s that had been scheduled for delivery in the fourth quarter or in early 2002, paying penalties that it considered "very fair and reasonable". This gave it a head start in dealing with the crisis.

However, some of those aircraft had new delivery dates in November, and Southwest subsequently decided that it did not want to take any aircraft at all until April 2002.

So the airline found a third party to finance and take delivery of all of the 19 aircraft (through an entity called the Amor Trust) and store them in the Mojave Desert until it is ready to buy them back.

The airline said that the deal had very favourable terms and gave it the flexibility it needed to tailor capacity to demand. It will now take 11 of the Amor Trust aircraft in 2002, beginning with the two in February, and the remaining eight in the early part of 2003. Separately, Southwest reached agreement with Boeing to defer 19 other 737–700s that were due to arrive in 2002. As a result, it reduced this year’s total deliveries from 27 to 11 aircraft. It is also looking to retire some of its older 737–200s.

Southwest has also delayed some of its 2004 deliveries to later years. The effect of the changes is to even out the delivery schedule over the next ten years; for example, 2005 previously had only five aircraft scheduled, now there are 24.

There have been no order cancellations.

Southwest’s total orders, options and purchase rights through 2012 have remained unchanged at 436 aircraft (of which 132 are firm orders). The airline has the option, which must be exercised two years prior to delivery dates, to substitute 737–600s or 737–800s for any of the 737–700s scheduled for post–2002 delivery.

At year–end, the aggregate firm order commitments added up to $3.6bn. This year’s funding needs are now only $322m, followed by $687m in 2003, $670m in 2004, $706m in 2005 and $1.26bn thereafter.

Strong liquidity position

Southwest entered the current industry crisis in a position of relative financial strength, with cash reserves of over $1bn, an unused $475m credit line and a debt–to capital ratio (including operating leases) of less than 40%. It also had 206 unencumbered aircraft, worth $5.4bn, of which 84% were Section 1110–eligible (offering special protections to note–holders in the event of bankruptcy). Consequently, raising liquidity was easy when the need arose after September 11.

First, on September 12, the airline drew down the $475m credit facility. A month later, it raised $614m in the capital markets in its first ever offering of enhanced equipment trust certificates (EETCs). As a result of those actions and the receipt of the initial government cash grants ($169m on a pretax basis), Southwest had well over $2bn in cash at the end of October.

The EETC was notable in that it was the first — and so far the only — totally new EETC offering brought to the market since September 11. Although American and Delta have successfully raised $1.9bn and $1.25bn respectively through EETCs since the attacks, those transactions had already been in the works before September 11.

Unlike American, which has only been able to tap the private market (rumouredly with manufacturer participation on the junior tranches) and has paid higher interest rates since September 11, Southwest did a regular public offering (which was six times oversubscribed) at a record low average interest rate of 5.53%. This reflected Southwest’s uniquely strong credit quality. Even in the depths of the current industry crisis, Southwest was regarded as the one certain long–term survivor.

It is worth noting that American went ahead with its main offering in late September only because it was truly desperate for cash, whereas Southwest chose the EETC market as the most efficient way of raising liquidity at that point. Prior to September 11 it had no plans to tap that source.

Collateral in the Southwest offering included 29 737–700s that were delivered between December 1997 and June 2001.

The EETC was notable in that it was the first — and so far the only — totally new EETC offering brought to the market since September 11. Although American and Delta have successfully raised $1.9bn and $1.25bn respectively through EETCs since the attacks, those transactions had already been in the works before September 11.

Unlike American, which has only been able to tap the private market (rumouredly with manufacturer participation on the junior tranches) and has paid higher interest rates since September 11, Southwest did a regular public offering (which was six times oversubscribed) at a record low average interest rate of 5.53%. This reflected Southwest’s uniquely strong credit quality. Even in the depths of the current industry crisis, Southwest was regarded as the one certain long–term survivor.

It is worth noting that American went ahead with its main offering in late September only because it was truly desperate for cash, whereas Southwest chose the EETC market as the most efficient way of raising liquidity at that point. Prior to September 11 it had no plans to tap that source.

Collateral in the Southwest offering included 29 737–700s that were delivered between December 1997 and June 2001.

Earnings outlook -the only profitable US major

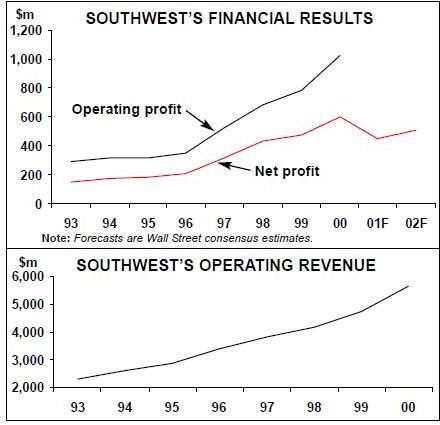

Southwest will be the only US major carrier to report a profit for 2001 (the results are expected on January 17). After previously anticipating a loss in the fourth quarter, the airline will now more or less break even.

Analysts' consensus estimate in early January was a very marginal loss of one cent per share in the fourth quarter.

As a result, Southwest’s full–year net profit is likely to be similar to the $448m reported for the first nine months of 2001. By comparison, the other eight major airlines are expected to report an aggregate net loss of around $6.8bn.

The current expectation is that Southwest’s net profit will improve to around $500m in 2002, though individual analysts' estimates range from just over $400m to $565m. The variation reflects differing views on the rate of economic recovery, improvement in industry fundamentals and the trend in fuel prices. Most analysts currently forecast industry losses in the $2–3bn range for 2002.

Southwest’s remarkable resilience in adverse economic or industry conditions has been reflected in its share price, which has shown relatively little decline or fluctuation since September 11. Over the past month or so, some analysts have downgraded the stock to "hold" or "neutral" — all based purely on price. When taking such action in early January, Salomon Smith Barney analyst Brian Harris pointed out that Southwest’s stock "tends to under–perform cyclical majors in the recovery part of the cycle".

Southwest’s executives have said that while the airline is keen to resume its long term growth plan, this year’s expansion may be below the normal 8–10% target.

There are still many unknowns — not just market conditions but also issues such as security costs, the availability of war risk insurance and airport costs. However, it is characteristic of Southwest to start with an extremely cautious attitude and then move aggressively.

| Firm | Options/ | Firm | Options/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| orders | purchase | orders | purchase | |

| rights | rights | |||

| 2001 (Sep 11-Dec 31) | 11 | |||

| 2002 | 27 | 11 | ||

| 2003 | 13 | 13 | 21 | |

| 2004 | 29 | 16 | 23 | 13 |

| 2005 | 5 | 18 | 24 | 20 |

| 2006 | 22 | 15 | 22 | 20 |

| 2007 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 29 |

| 2008 | 45 | 6 | 45 | |

| 2009-12 | 177 | 177 | ||

| TOTAL | 132 | 304 | 132 | 304 |