Southwest in the 21st century

January 2000

Southwest has been the airline industry’s commercial success story of the 20th century — consistently producing record earnings and the best profit margins in all the markets it has entered. Where will it go in the 21st century?

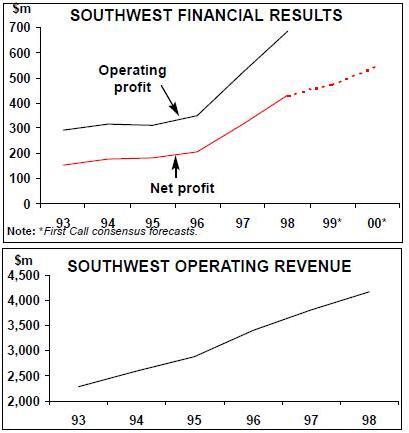

Southwest has been profitable for 27 consecutive years and has posted record earnings every year since 1991. Although its net income fell by 2.1% to $127m in the September quarter, this was due to a 32% increase in fuel prices. But revenues rose by 13%, the operating margin was still a spectacular 16.7% and the net margin was a near record 10.3%. According to PaineWebber, fuel–neutral earnings were up by 13%.

The reason for the much higher than typical fuel–price hike was that Southwest entered the third quarter unhedged, just as prices surged. After locking in the low fuel prices enjoyed a year ago for the first half of 1999, the carrier simply was not able secure those prices beyond the early summer.

The lack of hedging precipitated sharp falls in Southwest’s share price in the late summer, which seemed unwarranted as otherwise the trends have continued to be favourable.

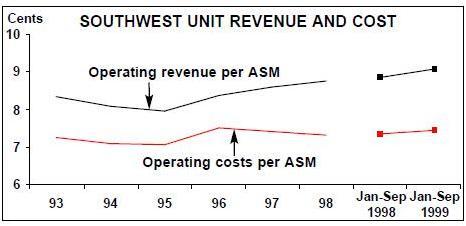

First, Southwest has done an excellent job in retaining its extremely low cost structure. Although costs per ASM rose by 4% to 7.55 cents in the September quarter, the 1999 figure will still be within the 7–7.5 cent range achieved throughout the 1990s. Excluding fuel, unit costs inched up by just 0.6% in the third quarter.

Second, the carrier has gone against the industry trend by posting strong and steady increases in unit revenues. Operating revenues per ASM have risen from around 8 cents in 1994 and 1995 to over 9 cents in 1999. Even the September quarter saw a 1.7% improvement to 9.07 cents, despite considerable industry–wide unit revenue pressures.

At the same time, load factors have continued to improve. Southwest’s average load factor in 1999 was running about three points above the 1998 level. November actually saw a 5.7–point improvement to a record 69.8%. The unit revenue and load factor trends are impressive in the light of the carrier’s rapid capacity expansion and head–on clashes with new competitors like Delta Express and MetroJet.

Southwest resumed its customary 10%- plus capacity growth last year, after a temporary dip to a 6.9% growth rate in 1998 due to the Boeing aircraft delivery delays (for which it received several million dollars as compensation). ASM growth accelerated throughout 1999, peaking at 13.9% in November and averaging 11–12% for the year.

While the strategy is to expand capacity by at least 10% annually, Southwest does not over–extend itself. Typically, most of the capacity is used to boost frequencies and only 2–3 new destinations are added each year.

This and the strong profits have enabled Southwest to maintain a healthy balance sheet. It currently has around $500m in cash, plus an available and unused bank credit facility of $475m, and its long term debt is a modest $650m. Its leverage, including off–balance- sheet aircraft leases, is less than 50%.

It enjoys top investment–grade credit ratings. Rather exceptionally by US airline standards, Southwest has paid quarterly dividends for 23 years (though the actual amounts are small). A three–for–two stock split was implemented in July, and in September the company announced a $250m stock repurchase programme.

Unique low-cost strategy

Many start–up carriers have copied Southwest’s basic short haul, point–to–point, high–frequency, low fare strategy, but have failed miserably. No–one has been able to emulate Southwest’s business model: low unit costs, a no–frills but otherwise exceptional service and a highly motivated work force.

The formula has worked so well for Southwest that there have been few, if any, changes. Just about the only strategic change in recent years has been the addition of more long haul flights, including coast–to coast services. That was mainly to mitigate the effects of new ticket taxes, which penalise short haul operations, and is very much seen as a complementary strategy.

Around 90% of Southwest’s flights are under two hours. The point–to–point operations have meant that 75–80% of its customers fly nonstop. High frequencies are a key part of the strategy — a typical business route has at least eight round trips a day and the biggest markets like Dallas–Houston and Oakland–Los Angeles have 25–40.

In contrast to a typical hub operation, where an airline might operate 500 flights a day from the hub and only 10–15 from spoke cities, Southwest operates numerous flights out of many different cities. At present it serves seven airports with over 100 flights a day. Were it not for the lack of connecting traffic, one could argue that Southwest is becoming a multi–hub network carrier.

Although Southwest has only a 5–6% share of the total US domestic traffic, it often dominates the markets that it serves. It is the largest airline in 83 of its top 100 markets. The airline attracts substantial volumes of business travellers because of its focus on things that matter most to that segment: high frequencies and punctuality. It has consistently come top or near–top of the DoT’s on–time performance, baggage handling and customer satisfaction rankings. It also offers high service quality and a generous FFP.

However, the biggest selling point are the low fares. When choosing new cities, the primary criteria is to go to markets that are overpriced and under–served. A typical one–hour segment might have highly restricted lowest fares of $300. Southwest will enter that market with $70 or $80 fares, and the market will triple or quadruple within one or two years.

This is the "Southwest Effect" — a term coined by DoT officials in a 1993 study to describe the dramatic traffic growth that usually follows after Southwest enters a market with low fares. Everyone benefits, not just Southwest, as competitors reduce their fares and the low fares persuade people to fly who did not fly before. But Southwest takes care not to provoke larger competitors. It avoids its rivals' hubs, using secondary airports or older terminals that bigger airlines snub.

Its unit costs are so low because of the efficiencies offered by a uniform, young 737 fleet (average age 8.5 years), rapid 20–minute turnarounds (just 15 minutes for 60% of the flights), favourable labour contracts and the use of cheaper, less congested airports.

One of the things that really sets Southwest apart from its rivals is the way it treats its employees. The company goes to great lengths to attract the right–quality staff, train them well and then motivate them to outperform their counterparts at other carriers.

Fortune magazine has included Southwest in its list of "the 100 best companies to work for in America" for two years in a row. The surveys have highlighted the importance of the personality cult around CEO Herb Kelleher in maintaining the corporate culture and the special "Southwest spirit". The company motto is "We take the competition seriously, but we don’t take ourselves seriously".

Workers are also motivated through competitive salaries and a profit–sharing programme, which was the first in the industry when it was introduced in 1973. Last year the company paid out $120m (based on 1998 profits), which represented 13.7% of eligible salaries. Through the plan, employees own about 13% of the company’s stock.

Success in the East

Much of Southwest’s growth over the past three years has focused on the East coast, where it had no presence before it entered Florida and Providence (Rhode Island) in 1996. Although service to Baltimore had been introduced in 1993, growth there did not take off until opportunities arose to link that city with other East coast points.

The Florida operation was an immediate success and was built up rapidly. In June last year Southwest also introduced service to American’s former hub at Raleigh/Durham.

However, over the past 18 months the focus has been on the Northeast, where Southwest has opened three new cities: Manchester (Rhode Island) in June 1998, Islip on Long Island (New York) in March 1999 and Hartford (Connecticut) in October 1999.

Each of these cities has been linked with Baltimore, Chicago Midway, Nashville and one of the Florida points, and frequencies have been built up rapidly. The East coast region now accounts for 21% of Southwest’s capacity (Southeast is 14% and Northeast 7%).

The process has elevated Baltimore to the ranks of the top ten Southwest cities, nearing the 100 daily flights mark this year. Southwest is now the largest carrier in terms of passenger boardings at Baltimore and has set up crew bases there.

All of this has created numerous direct competitive clashes with MetroJet, which also focuses on Baltimore. At times it has seemed as if the two were positively seeking each other’s company. They entered the Baltimore- Manchester market within a week of one another, and Southwest announced Hartford soon after MetroJet unveiled plans to expand service from that city.

But US Airways' strong East coast position has helped MetroJet survive, while Southwest appears not to have felt any impact at all. The impression gained is that all of its new markets have performed well.

The "Southwest Effect" has been especially strong in New England. The Providence–Baltimore market grew from 57,000 passengers in 1996 to more than 500,000 in 1997. The Manchester–Baltimore market grew from just 3,300 in the third quarter of 1997 to 115,300 passengers a year later. And passenger volumes at Hartford’s Bradley International Airport were up by 28.5% in November, the first month of Southwest’s service, with a whole host of carriers recording strong growth.

Little surprise, therefore, that Southwest’s presence is vied for by over 150 cities each year. There is no doubt that the airport authorities bend over backwards to accommodate its needs for quality facilities.

Southwest’s success in New England has proved wrong earlier speculation that its costs would rise due to severe winter weather, congestion and other challenges posed by the Northeast environment. Strict adherence to the rule that the costs of operating from each airport must be in line with its overall cost structure has obviously helped.

Southwest also appears to have proved wrong the sceptics who argued that it could never succeed in serving the tough New York City area market from a place like Islip. Operations from there will be expanded to Nashville and Florida in February or March as more aircraft are delivered.

Fleet and financing plans

Southwest became the launch customer for the 737–700 in December 1997 and expected to receive its 57th aircraft by year–end. The type will become its main workhorse and cater for growth over the next decade and beyond. The 737–700 will also significantly help it retain its unit cost advantage over competitors.

Since the original 1993 order, Southwest has come back several times to exercise options and place more orders. Most of the 85 currently on firm order are due for delivery over the next three years, so there will be more orders and used aircraft acquisitions to facilitate growth from 2002. The 737–700 options (currently 65) have delivery slots spread out from 2003 to 2006.

The fleet also includes 195 300–series, 35 200–series and 25 500–series 737s. The size of the 300–fleet has continued to increase slightly as a result of used aircraft acquisitions. The -200s are being gradually retired, though the intention now is to retain at least the hush–kitted ones through this year. The airline generally keeps the -200s for 75,000 cycles or for 20–22 years.

Over the past couple of years, operating cash flow has accounted for about 90% of Southwest’s capital spending. The carrier has been able to self–finance since 1995 and has not raised any fresh capital for all practical purposes in recent years. However, it did raise some external financing in the fourth quarter. This year’s capital expenditure is expected to amount to $1bn, compared to $1.2bn in 1999.

Outlook for 2000 and beyond

Southwest’s CFO Gary Kelly said at a recent conference that while there is reason to hope that the strong traffic and revenue trends would continue, it would be a "very difficult" first–half of the year for fuel price comparisons. This is because the carrier did an excellent job with hedging in the same period in 1999, rather than the price of fuel being outrageously high at present. However, the non–fuel cost structure looks very good and the aim is to drive those costs down further. The carrier is fortunate in that, apart from talks with the fleet service workers (TWU) that began in early December, no other labour contracts of any significance will become amendable for another two years.

In late 1998 the pilots voted overwhelmingly to keep the second half of a 10–year contract signed in 1994, which froze the pay scale for the first five years in exchange for a substantial number of stock options.

The pilots felt that they had been compensated to a greater degree than would have been possible through pay rises, though sweetened terms over the second half of the contract also helped.

The addition of 31 737–700s and the retirement of two 737–200s will lead to ASM growth of around 12% this year. At least two new cities, and possibly as many as four, will be added to the network in 2000.

The current First Call consensus forecast is a net profit of $1.02 per share for 2000, which would represent a 14.6% increase over the 1999estimate of 89 cents. Most analysts currently rate Southwest as a "strong buy", which reflects its low share price and the usual rally in airline shares anticipated over the winter and the early spring.

But Southwest obviously possesses many attributes that give it unique long–term potential in an industry characterised by volatility. The key ones are its consistent profit record, unaffected by the economic cycle, and proven business formula. It is also well–positioned for the Internet age (being the first major to offer online bookings and, before that, the first to go ticket–less system–wide). CIBC analyst Sal Colak recently suggested that investors should view Southwest as the only long–term hold in the airline sector.

Succession has become slightly more of an issue since 68–year–old Kelleher underwent treatment for prostate cancer last year. However, Kelleher appears to have made a full recovery and has no plans to retire. Efforts to function more smoothly as a team may have made his role less critical.

Given its success in the domestic market, the fact that its network now spans the entire continental US and the stated long–term aim to grow by at least 10% annually, when will Southwest go international?

The standard answer, reiterated by Kelly, is that there are still lots of good growth opportunities or "a good 5–10 years of development to do" in the US. It is much easier for Southwest to contemplate expansion in markets that it knows and where the addition of new flights and cities also helps to develop the existing route system. It does not know the international business and could not leverage such expansion on existing markets.

Southwest has identified "at least another 55" potential US cities (and it is worth noting that it has taken 25 years to get to its present total of 55). The cities to be added are obviously getting smaller, but the experience has been encouraging. For example, Jackson (Mississippi), which was added in 1997, is very profitable with 10–12 daily flights.

While Canada and Mexico would not pose too much of a risk and could be served with the 737–700s, Kelly says that opportunities still look better in the US at present. However, he believes that international expansion will follow in the longer term. Southwest has no alliances or code–shares in place. First, it simply does not focus on connecting passengers. Second, it does not want to change its schedules or operating practices, which facilitate quick turnarounds and maximise aircraft utilisation, to optimise connections with an alliance partner. Third, it does not want to jeopardise on–time performance or service quality (though it would still consider proposals that add incremental traffic).

By Heini Nuutinen

| Current | Orders | Options | Delivery/retirement schedule | |

| fleet | ||||

| 737-200 | 35 | 0 | 0 | |

| 737-300 | 195 | 0 | 0 | |

| 737-500 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| 737-700 | 57 | 85 | 62 | Firm orders by end of 2004, |

| TOTAL | 312 | 85 | 62 | options in 2003-2006 (see below) |

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 TOTAL | ||

| Firm orders | 31 | 23 | 21 | 5 | 5 | - | - | 85 |

| Options | - | - | - | 13 | 13 | 18 | 18 | 62 |

| TOTAL | 31 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 147 |