Branson: the wizard of Oz?

January 2000

Lessons of Virgin Express

Richard Branson, owner of Virgin Atlantic and part owner of the floated Virgin Express, has announced his intentions to start up a low cost airline in the Australian domestic market. What lessons can be learnt from the none–too–successful Virgin Express operation? Can Virgin Australia succeed where the previous generation of low cost carriers — Compass Airline and Southern Cross — failed? Brussels–based Virgin Express is many observers' favourite to be the next European airline failure, following the demise in 1999 of carriers such as AB Airlines, Color Air, and Debonair.

Virgin Express has been a very poor stock market performer: it is currently rated 64% below its 1997 flotation price. Some of Virgin Express’s problems are outside its control but most could have been foreseen.

- Conflict with the Belgian authorities

It is not easy to run an airline (nor any company) out of Belgium. Labour costs are inflated by government social charges which add about 37% to the basic salary compared to around 10% in the UK and other countries. Faced with what is regarded as unreasonably high pilot costs and inflexible work rules, Virgin Express’s management made last year (1999) a decision to concentrate future growth in Shannon, Ireland where they already had five 737s based. This provoked a review of the carrier’s AOC by the Belgian Civil Aviation Administration (BCAA). The BCAA was specifically concerned that the airline’s AOC covered only Belgian–registered aircraft and that plans to shift the main operation to Ireland was a flag–of–convenience tactic.

Virgin Express has responded by arguing that it is not labour costs that are driving it to Ireland, but an inability to hire Belgian pilots. The airline claims that it has only enough Belgian crews to man nine of its total of 16 Belgian–registered aircraft.

- Cultural problems

The airline has also admitted to cultural differences between the former US senior management team under Jonathon Ornstein, imported from Mesa Airlines in New Mexico whence they have returned, and the European workforce. It wasn’t just the brasher American style, it was the fact that they imported a US product but didn’t seem to understand that it had to be adapted to a new environment. By contrast, Ryanair and easyJet have borrowed all the key low–cost strategies from the US, but have given them a uniquely European feel.

The recent appointment of John Osborne (formerly GB Airways) as CEO may be significant; certainly he is more likely to appease the Belgian authorities who have now granted a four–month extension to the airline’s AOC.

- The relationship with Sabena

Virgin Express more or less had to forge a code–share/block seat agreement with Sabena in order to gain access to Sabena’s slots at Heathrow. However, the agreement meant that Sabena sold the business cabin, leaving Virgin Express just with Economy and hence unable to replicate its very successful Virgin Atlantic product within Europe.

Cooperation between the two airlines has always been strained, and the relationship is inevitably coming under stress as competition between the two carriers grows — for example, Virgin Express competes with its own service from Brussels to London Stansted. The arrival of Sabena’s new A319s in 2000 may terminate the agreement.

- The route network

The network has little in the way of coherence. Apart from London Stansted and possibly Shannon, Virgin Express flies to some of the highest cost airports in Europe. This is anathema to Europe’s leading low cost carrier, Ryanair. From its primary hub at Brussels National, only three destinations have a daily frequency in excess of four flights — London (split between services to Stansted, Heathrow and Gatwick), Barcelona and Rome. Six other European cities are served from Brussels but for the most part only have one daily departure.

Virgin Express’s timetable shows many connecting opportunities over Brussels but the only points linked with more than three daily frequencies are all from London — to Barcelona, Copenhagen, Madrid, Milan, Rotterdam and Rome. All these have very attractive direct services offered either by flag–carriers or by other low cost airlines. Virgin Express must have to operate at the most price–sensitive and therefore lowest–yielding end of the market So the Virgin Express formula is unlikely to be replicated in Australia, and Richard Branson will presumably have learnt the lessons of Virgin Express in his new venture Virgin Australia.

There are similar traps to fall into in the Australian market with its history of heavy unionisation and bureaucracy.

Prospects for Virgin Australia

Virgin Australia is slated to begin operations in July 2000, well before the Sydney Olympics in September 2000. The low cost airline will be aimed primarily at Australia’s trunk routes and plans to offer at least 50% of its available capacity at fares that are half the level of today’s discounted ticket prices, for example, A$100 (US$63) for a single fare on Sydney–Melbourne, a distance of some 750km.

Although Branson has indicated that he expects his airline to mostly stimulate its own demand and so not significantly impact the incumbents, this was not a view shared on the Australian stock market. On the day of the announcement, A$780m (US$490m) was wiped off the value of Qantas shares.

Branson appears to have played an astute political game. The Australian Foreign Investment Review Board has given the airline the go–ahead, a major hurdle in that it is one of the few and perhaps only example of a country granting a nonresident domestic cabotage rights. The argument that the incumbents have failed to compete effectively and that the travelling public has lost out badly is a powerful one.

He has also held meetings with Australian Prime Minister John Howard who apparently has given Branson assurances that the Government would invoke anti–competitive legislation to ensure that there is fair competition.

These reassurances are significant. Ansett and Qantas have been able to keep a duopoly grip on the vast majority of major domestic routes and have in the past seen off new entrants. In the case of Compass, the original airline using A300s failed in 1991, and after restructuring as an MD- 80 operator, failed again in 1993.

The Virgin name is known in Australia through the various Virgin brands, though on nothing like the British scale. Lucky Australians can look forward to seeing a lot more of Branson. The Virgin Holidays company will also no doubt have a part to play in the success or otherwise of the new venture. Australia is becoming a very popular tourist as well as VFR destination, and as part of an extended stay in the country, domestic air travel is a prerequisite.

Virgin Australia is expected to start operations with five 737–300s, and eventually serve most of the country’s major population centres. The airline will be launched with an initial start–up capitalisation of US$30m (no problems after the SIA sale) and with a target of carrying 3m passengers a year (about 15% of the current market). Australia is a classic example of a country where a low cost operation should be successful.

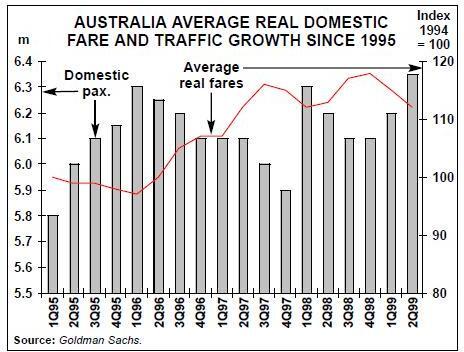

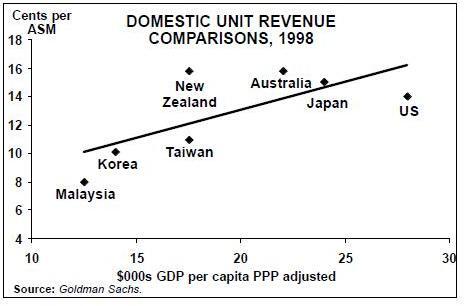

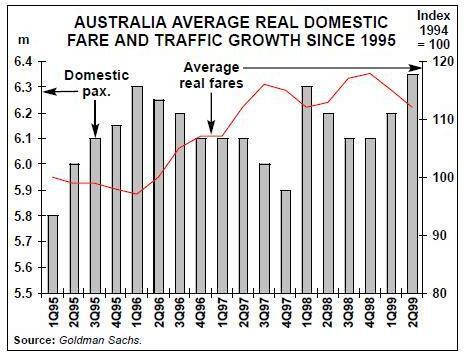

Rail and road travel is generally not a good substitute for air travel, and distances between major towns and cities are large. Air transport remains relatively high yield–low volume, as opposed to the US market, which is high volume–low yield. Yet the Australian market is highly price–elastic: during Compass’s foray into the market, between 1990 and 1992 fares fell by 30% on average which stimulated a 60% increase in passenger volumes at a time when the economy was in recession.

Impact on Ansett and Qantas

Branson’s assertion that Virgin Australia will have little impact on the incumbents is clearly wrong judging by their reactions — stalling tactics, threats to match any fares offered, denying access to airline owned terminals because of lack of space, planning to start up their own low cost subsidiaries etc. Virgin Australia will inevitably have a significant cost advantage over Ansett and Qantas. The incumbents enjoy a well–established duopoly, and only minor fluctuations in market shares have been the norm. Both airlines carry significant overheads and the heavily unionised workforces have established working practices and pay scales to match.

However, the reaction of the stock market is equally over the top. The European experience is that new entrants do stimulate markets and precipitate necessary costs cutting and efficiency improvement strategies in the incumbent carriers.

Aer Lingus is a European example of a full service carrier that learnt to co–exist and compete successfully with a low cost airline, Ryanair (see Briefing, November 1999).

The weapons in the armoury of the incumbents are branding, Australian loyalty, and capacity. Both carriers are leading members of global alliances, Qantas with oneworld, Ansett with Star, and are members of global frequent flier programmes. The loyalty programmes will presumably be used aggressively to retain premium passengers.

Both Qantas and Ansett will need to adopt carefully thought–out yield and capacity management strategies if they are not to lose unacceptable market shares. More aggressive pricing of unused off–peak capacity is just one weapon that will be used to compete. But such pricing policies may come under scrutiny from the regulatory authorities, which have already been alerted by Branson.

Airport strategy

Apart from Sydney, all of Australia’s airports have been privatised, and will presumably be prepared to offer some sweetheart deals to Virgin Australia. But the new airline faces two problems.

First, there are few secondary airports in Australia. A possible exception is at Melbourne where Avalon Airport represents a possible alternative to the main BAA–managed facility.

Second, although slot availability is not generally an issue in Australia, there is a severe slot shortage at Sydney. Virgin Australia has been provisionally awarded 26 slots at Sydney but very few of these are likely to be at peak times.

A further problem at Sydney is a lack of terminal space. Apart from the common user terminal at Sydney, which is used for international flights, the only other two terminals are owned by Qantas and Ansett and are virtually running at maximum capacity.

In the short–term, the Australian Government will insist that gate facilities are made available by one of the incumbents. In the medium term there is the prospect that a new domestic passenger terminal may be built to house both Virgin and other domestic start–ups. According to the airport itself, this could be up and running within six months of being given the go–ahead.

Branson should be able to produce an airline with a significant cost advantage, one that must mirror the Southwest/Ryanair model rather than the Virgin Express model (i.e. truly low cost and focussed on point–to–point traffic offering high frequencies). But even before Virgin Australia is launched it has bred imitators — Spirit Airlines has announced a start–up of operations in June 2000, initially with two 737–400s on Melbourne–Sydney and Melbourne–Brisbane at fare levels that would undercut Virgin’s.