Avianca: United

in Synergy

Jan/Feb 2019

Recent months have seen notable developments involving Synergy Group’s Avianca brand airlines that have drawn global attention, may aid Latin American airline recovery in 2019 and could even lead to structural change in the sector.

First, on November 30, United Airlines, Colombia’s Avianca and Panama’s Copa announced a three-way joint business agreement (JBA) on US-Latin America routes (excluding Brazil), for which they plan to seek antitrust immunity. The three airlines were already Star and codeshare partners.

Second, in conjunction with the JBA, United agreed to provide a $456m term loan to Brazil’s Synergy Group, the controlling shareholder (through Panama-based Synergy Aerospace Corp) of Avianca’s parent Avianca Holdings (AVH).

Third, on December 11, Avianca Brasil filed for the Brazilian equivalent of Chapter 11 bankruptcy (known as “Judicial Recovery”) in response to lessors seeking to repossess 30% of its fleet. Avianca Brasil is Brazil’s fourth largest airline, 100% owned by Synergy Group and not part of Avianca Holdings.

Fourth, on December 13, Brazil’s outgoing president Michel Temer signed a temporary decree allowing 100% foreign ownership and control in Brazil’s airlines (which Congress must approve within 180 days). The move came after almost a decade of attempts to lift the previous 20% limit.

So what are the implications for Avianca, Avianca Brasil and the Latin American aviation scene?

Colombia’s Avianca secured the strategic partner it had long sought and now looks certain to be a long-term survivor and perhaps even an A-list player — especially if it can reach agreement with Airbus and lessors to restructure its order book.

United will get its first immunised JBA on US-Latin America routes. The deal will balance the line-up that already includes American-LATAM and Delta-Aeroméxico. It should help facilitate better capacity management in the region.

However, obtaining regulatory approvals for the JBA from 20 countries is likely to take at least 18-24 months.

Avianca will not receive any funds at this stage, because Synergy will use the United loan to pay off earlier borrowings from New York-based hedge fund Elliott Management, for which it had pledged its Avianca stake as collateral.

But the United loan is also secured by Synergy’s stake in Avianca, and Synergy has the option to pay part of the loan back in AVH stock, which raises the interesting prospect of United ending up with a stake in or even control of Avianca. It would not be a bad outcome for United in light of Latin America’s enormous long-term potential. Some would also see it as a positive for Avianca, because it would lead to better corporate governance.

The JBA signatories will have to decide how to include Brazil in the partnership. Will Azul and Avianca Brasil be drawn in? Or will United seek a separate immunised JV with Azul for the US-Brazil routes?

Having already downsized and returned some aircraft, Avianca Brasil is now focused on preventing further repossessions, securing new funds and getting a reorganisation plan approved by creditors at a meeting scheduled for early April. Beyond survival, the key questions are: How much will Avianca Brasil downsize in bankruptcy and who will benefit the most? Will Azul or United acquire a restructured Avianca Brasil and merge it with Azul, thus consolidating Brazil’s airline sector from four to three main players?

At this stage it seems unlikely that another foreign airline buyer for Avianca Brasil would emerge, despite ownership in Brazil’s carriers being wide open to outsiders. One thing seems certain: it is only a matter of time before Delta and United increase their stakes in GOL and Azul, respectively (currently 9% and 8%).

The JBA and United loan

Avianca officially began to look for a strategic partner in mid-2016 and received three offers. But Synergy did not want to give up control, which ruled out two of the bids (from Delta and Copa).

The subsequent negotiations with United for the JBA/loan were a difficult and long-drawn out affair. There was a lawsuit from Avianca’s minority shareholders seeking to block a deal with United as “egregiously one-sided” (settled in late 2017). Synergy’s attempts to integrate Avianca Brasil into Avianca Holdings, as well as its search for a cash injection into Avianca Brasil at the same time as negotiating a loan for Avianca, evidently also complicated things.

The two airlines are legally separate, but Avianca licences its brand to the São Paulo-based carrier (whose official name is Oceanair). The two Efromovich brothers who own Synergy, Germán and José, act as chairmen of Avianca Holdings and Avianca Brasil, respectively.

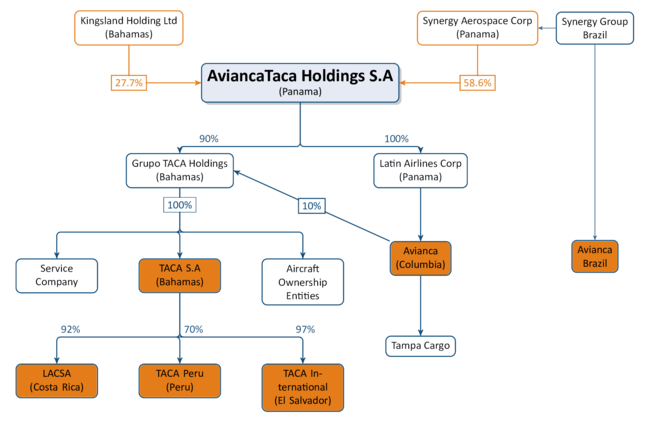

Although Synergy has a controlling stake in Avianca Holdings (51% of total shares and 78% of voting rights) and minority investor Kingsland Holdings (the Kriete family, former owners of TACA) has 14% (with 22% of the votes), the latter has veto powers over strategic decisions (and has used them to block decisions such as bringing Avianca Brasil into AVH).

The terms of the $456m loan from United to Synergy and the details of the separate agreement between United and Kingsland are worth noting because they outline multiple paths for United to potentially become a part or full owner of AVH.

The loan bears interest at 3% annually and is payable in five annual instalments from 2021 to 2025. Synergy may pay up to 25% of any instalment in AVH shares. United also has an option to acquire up to 77.4m AVH shares from Synergy, and it will get a board seat if the stake reaches 5%. The loan is secured by the 516m common shares Synergy holds in AVH.

The agreement with Kingsland ensures the minority shareholder’s cooperation and the availability of Kingsland’s 144.8m shares in AVH in certain circumstances. In return, United granted Kingsland the right to put its AVH shares to United at market price on the fifth anniversary of the agreement. Also, United guaranteed Synergy’s obligation to pay Kingsland if AVH’s ADR price is less than $12 on the fifth anniversary, ensuring that Kingsland would see an annual return of at least 18%.

In Aviation Strategy’s back-of-the-envelope calculations, assuming that Avianca pays back 25% of the loan in shares, United exercises its stock options and Kingsland exercises the $12/ADR put option, United could end up with 33% of the equity and 50% of the voting rights in Avianca Holdings (depending on share price performance to 2025) for around $450m, which compares with a possible current market capitalisation of $585m.

The JBA, which United hailed as the “next chapter in US-Latin America air travel”, will cover 275-plus destinations and some 12,000 city pairs.

According to Flightglobal, Avianca, Copa and United had a combined 26% share of the total US-Latin America capacity in 2018, compared to American-LATAM’s 32% and Delta-Aeromexico’s 17%. However, United and Delta have not yet sought immunised JVs with their Brazilian partners.

Avianca, Copa and United said that they were “exploring the possibility” of adding Brazil to the JBA. Azul is the leading candidate, with United owning 8% and the two codesharing extensively. But United will have to decide if an immunised United/Azul JV would be more effective in countering a future Delta/GOL JV in the important US-Brazil market.

Avianca: new action plan

Since it will not receive any of the UAL loan proceeds, Colombia’s Avianca will have to find other ways to strengthen its balance sheet. However, there is no urgency as AVH’s financial position is quite stable, thanks to consistent profits and a strong market position.

Founded in 1919, Avianca is the oldest airline in the Americas. Its past includes a brief Chapter 11 visit in 2003-2004, when it lost its original NYSE listing. Synergy bought it out of bankruptcy in 2004 and turned it around quickly, revamping its customer service, renewing its fleet and expanding its network.

Having also acquired Colombian carrier Tampa Cargo and Ecuador’s Aerogal, in 2010 Synergy merged Avianca with El Salvador’s Grupo TACA — an early pioneer of the multi-country, multi-airline strategy in Latin America. The merger created a holding company for 11 airlines from nine countries.

At that point Avianca had five solidly profitable years under its belt, with operating margins in the 7-13% range. It went public in Colombia in 2011 and relisted its stock on the NYSE in 2013. It joined the Star alliance in 2012.

In 2013, as the last major step in successful merger integration, the combine moved to a single brand. Nine of the 11 airlines that are currently consolidated under the holding company use “Avianca” as their commercial name, while maintaining their separate legal and labour structures (see table). Two other airlines that are owned directly by Synergy, Avianca Brasil and Avianca Argentina, use the name through brand licence agreements.

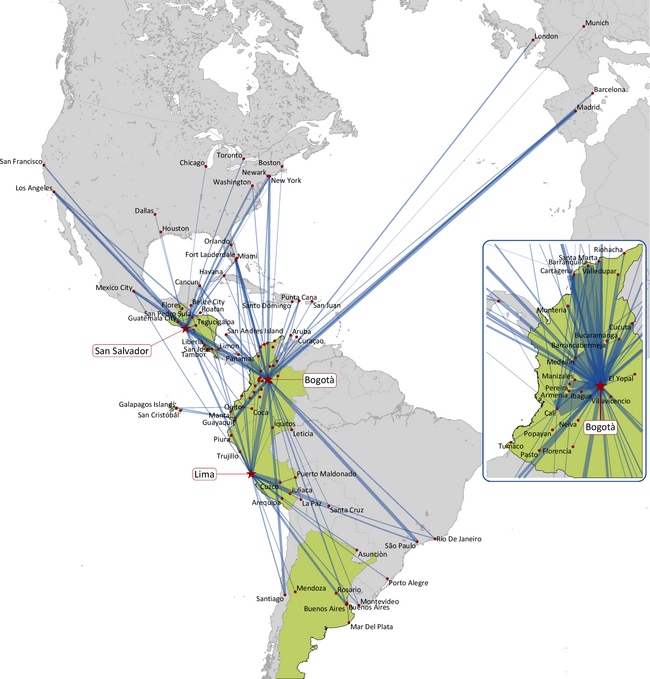

Avianca Holdings has grown its capacity at a brisk 6-10% annual rate in the past seven years (2017 was the exception when growth slowed to 2.7%), consolidating its position as the second largest airline group in Latin America. The network is diversified, with domestic operations in five countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Peru) and international operations throughout the Americas and the Caribbean, as well as to four destinations in Europe. There are three strategically located hubs (Bogotá, Lima and San Salvador) and focus city operations in Costa Rica, Quito and Guayaquil.

The group has a strong position in certain key Latin American markets, including a 54% domestic market share in Colombia and 64% of the international traffic between the five “home markets”. In longer-haul international markets (where foreign carriers tend to dominate), AVH has respectable 26-33% traffic shares.

Still, Avianca Holdings is less than half of LATAM’s size, with around $4.9bn revenues in 2018 compared to LATAM’s $10.4bn. Four of the nine airlines are very small regional operators with mainly turboprop fleets.

Avianca has built a strong brand associated with a superior customer service. It has been recognised as “best airline in South America” on both long-haul and short-haul flights by Skytrax and others. At the same time Avianca also has a competitive cost structure, but its labour relations are difficult, as was illustrated by an illegal seven-week pilot strike in 2017 that dented that year’s operating profits by $126m.

Avianca’s cost structure benefits from having one of the youngest passenger fleets in Latin America, with an average age of 6.9 years at the end of 2017. The passenger fleet has been streamlined on the A320/A320neo-family, the A330 and the 787. Around 72% of the total fleet is owned, with the remainder being on operating leases. The firm order book is substantial: 124 A320neo-family aircraft scheduled for delivery in 2019-2025 and three 787-9s in 2019.

Since the merger with TACA Avianca’s profits have been relatively low but stable, with operating margins in the 5% to 8.4% range and net margins typically 1-3%. The operating margins have lagged those of other Latin American carriers mainly because of intense LCC/ULCC competition in Avianca’s key markets.

In the Colombian domestic market, Avianca competes with VivaColombia, Copa’s Wingo, LATAM’s lower-cost unit and others. The Central America region has become a hotbed of LCC competition; notably, Mexican ULCC Volaris expects to have an El Salvador-based unit operational this summer, after launching Volaris Costa Rica in 2016. US-Colombia has been a huge growth market for US LCCs in the past decade.

Avianca’s net results are weighed down by heavy interest expenses. As of December 2018, Avianca had long-term debt and capital leases of $3.4bn and total liabilities of $6.1bn. Total assets were $7.1bn and book equity $978m. Its adjusted net debt/EBITDAR ratio was 6.2x. Cash reserves amounted to only $389m (8% of last year’s revenues).

Most of Avianca’s debt is aircraft-related and the interest rate on the long-term financings averaged only 3.48% at the end of 2017. But, as Fitch noted last year, upcoming debt maturities are relatively high for the airline’s liquidity position and projected free cash flow generation. As of September 2018, Avianca had $2.1bn or 52% of its total long-term bank debt and bonds coming due within three years. The 12-month period from October 2019 looks especially challenging with $1bn of scheduled maturities (mostly in 2020).

Last spring both S&P and Fitch affirmed Avianca’s ‘B’ credit ratings, saying that they expected Avianca to cover its capex and debt maturities from cash flow, debt refinancing and some incremental borrowing. However, Fitch flagged two areas of concern: liquidity position and a growth strategy requiring “material spending on aircraft deliveries over the next few years”.

Avianca placed a $10bn order with Airbus for 100 A320neo-family aircraft in 2015. The following year it deferred $1.4bn of 2016-2019 deliveries. As a result, its A320neo deliveries will rise sharply in 2020, to about 20 each year. Its total aircraft commitments will surge from $290m in 2018 to $972m in 2019 and $2.1bn in 2020.

The airline has been talking with Airbus and lessors to significantly slow the introduction of new aircraft. The company said in its FY2018 results call that it had an agreement in principle with some suppliers, and that there would be a “material reduction” in commitments. A significant order book restructuring would enable Avianca to accelerate deleveraging.

Under its “transformation” plan, Avianca has changed its focus from growth to profitability; it is guiding only 0-2% ASK growth in 2019 compared to last year’s 8.7%. It plans to cull the fleet from 190 at the end of 2018 to 150-165 in 2020 including the disposal of its 10 E190s this year. The six key pillars of the plan are to adjust aircraft commitments, improve operational efficiency, divest stakes in most non-core business units, optimise the network, strengthen capital structure and re-prioritise capex-intensive projects.

The decision to focus on three core units (airline business, cargo and loyalty) and shed marginal activities represented a U-turn from the earlier strategy of diversification. A streamlined group structure, together with segment reporting (to begin in the current quarter), could make it easier for Avianca to attract investors.

Notably, the JBA and closer relationship with United have already led to significant corporate governance improvement at Avianca. In the Q4 call, the airline unveiled reforms to the structure of its board, aimed at ensuring “impartial decision-making” and “balanced involvement and input” from all shareholders. The reforms include a new “board executive committee”, more independent directors and United sitting in meetings as an observer.

Avianca’s market position should benefit from being part an immunised JV and having United as a strategic partner. CEO Hernán Rincón said recently that Avianca was seeking a similar alliance with Lufthansa. Avianca is keen to expand in Europe with its growing fleet of 787s; it launched the Bogotá-Munich route in November and is now considering adding Zürich, Rome and Paris to its network.

Who will rescue Avianca Brasil?

Avianca Brasil’s December 2018 bankruptcy was in some ways surprising. The airline has been successful in the marketplace, offering a blend of full service, generous seat pitch and low fares. It has consistently achieved load factors 3-4 points above the industry average. Its extensive slot holdings at key airports made it possible to build a network focusing on potentially lucrative trunk routes. It has been Star’s sole representative in Brazil since joining the alliance in 2015.

But reckless growth through Brazil’s recession, a prolonged weak domestic revenue environment and a chronically weak balance sheet meant that Avianca Brasil could not withstand 2018’s severe fuel and currency headwinds.

Avianca Brasil’s strategic position was weak as industry consolidation in Brazil had left it in a more distant fourth place in the domestic market. So it began to grow extremely rapidly; its ASK growth averaged 37% annually in 2010-2014.

The big mistake Avianca Brasil made was to continue heady growth through Brazil’s deep three-year recession. In 2016, when industry capacity in Brazil contracted by 6% (and even Azul slashed capacity), Avianca Brasil grew its domestic ASKs by 14.1%. Its growth continued at the 13-15% level until mid-2018.

In July 2016, as most Latin American airlines were deferring aircraft deliveries, Synergy placed a $6.6bn order with Airbus for 62 A320neo family aircraft for Avianca Brasil.

In 2017 Avianca Brasil went international, launching services to Chile, Colombia and the US.

As a result, Avianca Brasil did increase its market shares. Its domestic RPK share rose from 2.4% in 2010 to a respectable 14.4% in April 2018, though this was still four points behind Azul’s market share. Internationally, Avianca Brasil accounted for 8% of Brazilian carriers’ RPKs in November 2018, which was not so far off Azul’s and GOL’s shares of around 12% each.

But the economics of its business model are questionable. While Avianca Brasil’s unit costs are higher than GOL’s (more upmarket product, smaller size, mostly leased fleet), in recent years its unit revenues have been lower than GOL’s.

Avianca Brasil’s filings with ANAC have indicated many years of weak results (losses or marginal profits) and then heavy losses last year. The net results, like those of other Brazilian carriers, have fluctuated depending on currency movements. The airline had a net loss of R$71.4m in 2016, a net profit of R$41.6m in 2017 and a net loss of R$176m in H1 2018.

Last year’s second quarter (the latest quarter available for Avianca Brasil) was tough for all Brazilian carriers because of the triple whammy of higher fuel prices, a weak real and a lengthy truck drivers’ strike. But Azul and GOL still achieved small operating profits, whereas Avianca Brasil had a negative -28% operating margin (R$259m EBIT loss on revenues of R$938m).

Avianca Brasil was vulnerable because its balance sheet was in very poor shape. It had unrestricted cash of only R$38m ($10.2m), adjusted net debt of R$5.1bn ($1.4bn) and net debt/EBITDAR of around 11x in June 2018.

Last summer it finally began reining in growth and said that it was seeking to reduce its fleet by eight aircraft. In early December Avianca Brasil returned four aircraft to lessors. The Chapter 11 filing came when three lessors sought to repossess an additional 14 aircraft. Avianca Brasil reportedly owed lessors more than $100m and suppliers another $125m.

The initial 14 December bankruptcy court hearing in São Paulo suspended aircraft repossessions for 30 days and other lawsuits for 180 days. Avianca Brasil was ordered to present a “judicial recovery plan” by mid-February.

Since the 30-day stay on repossessions expired in mid-January, Avianca Brasil has been fighting to keep the 20 or so A320s it leases from Aircastle and GECAS. And on 1 February the bankruptcy judge ruled that it could continue operating the aircraft until mid-April.

In many such instances lessors would have helped an airline, but Avianca Brasil had a poor track record. It had already been sued once for missed lease payments (by Avolon in 2016). One of its two main lessors, Aircastle, is heavily exposed with Avianca Brasil being its largest customer.

Avianca Brasil secured more time in part because it agreed to return eight aircraft, including four A330s. It is ending nearly all international service at the end of March (retaining only Bogotá) and is reducing its workforce by 600 or 11%, with more expected to go on unpaid leave.

Importantly, Avianca Brasil has found external backers. According to an early-February court filing, three hedge funds controlled by Elliott Management have agreed to provide $75m in capital in the form of convertible debt. And Aircastle confirmed in mid-February that the airline had resumed lease and maintenance reserve payments on 1st February, as stipulated by earlier court orders.

Avianca Brasil has filed a judicial recovery plan, which calls for the transfer of its aircraft and slots to a new company (“Life Air”) that would be sold to pay off the debts. The new entity would have revenues of R$4bn, EBITDAR of R$925m and net earnings of R$96m in year one. The Elliott loan would convert to a 49% equity stake, and creditors and lessors would be able to take part in the capitalisation.

Avianca Brasil also has new leadership in place. Jorge Vianna, one of OceanAir’s founders, has taken over as president from Frederico Pedreira.

However, ANAC obtained an injunction that allows it to deregister any leased aircraft operated by Avianca Brasil if a lessor requests it. The move was in response to criticism that Brazil was not complying with the provisions of the Cape Town Convention — something that lessors have warned could lead to higher lease rates for all Brazilian airlines. Avianca Brasil has appealed to the Superior Tribunal de Justiça, and as yet, no lessor had submitted a deregistration request. Aircastle and GECAS, though, have continued to try to repossess aircraft through the bankruptcy court: a hearing about 23 aircraft is scheduled for 11th March.

Bradesco analysts have predicted in recent reports that Avianca Brasil will have to shrink further in order to emerge from bankruptcy, because even if the judicial recovery plan is approved by creditors in April, it could take up to six months to conclude the financial transactions.

Azul would be the obvious candidate to make a bid for Avianca Brasil; it is growing and the two airlines have less than 10% network overlap. Their combined domestic market share of 31% (November 2018) would create a strong third carrier for Brazil.

According to Flightglobal, Azul has expressed interest in some or all of Avianca Brasil’s A320neos. Azul operated 20 of that type at year-end and in January it added two A320neos that were previously leased to Avianca Brasil by BOC Aviation.

One thing seems certain: Brazil’s airline industry will benefit. All possible scenarios — be they Avianca Brasil’s contraction, disappearance or absorption into Azul — will lead to a capacity reduction in the domestic market, giving airlines more pricing power. GOL, with its 80% network overlap with Avianca Brasil, could benefit the most.

| Unit | Alternative or former name | Details | Country | Ownership Interest | Stake held via |

| Main airlines | |||||

| Avianca | Aerovias del Continente Americano | National airline (est. 1919) | Colombia | 99.98% | |

| Avianca El Salvador | TACA International Airlines | National airline (est. 1931) | El Salvador | 96.84% | TACA |

| Avianca Costa Rica | LACSA | National airline (est. 1945) | Costa Rica | 92.40% | TACA |

| Avianca Ecuador | Aerogal | Est. 1986; Acquired 2008 | Ecuador | 99.62% | |

| Avianca Peru | Trans American Airlines/TACA Peru | Est. 1999 | Peru | 100% | TACA |

| Avianca Cargo | Tampa Cargo SAS | Est. 1973; Acquired 2008 | Colombia | 100% | Avianca |

| Small regional or cargo operators | |||||

| Avianca Guatemala | Aviateca | Est. 1929/ATRs | Guatemala | TACA | |

| Avianca Honduras | Islena | Est. 1981/ATRs | Honduras | 100% | TACA |

| Avianca Nicaragua | La Costena | Est. 1999/ATRs | Nicaragua | 68% | TACA |

| SANSA | Est. 1978/Cessna Caravans | Costa Rica | 100% | TACA | |

| AeroUnion | Cargo/Est. 1998/A300F/767F | Mexico | 92.72% | Tampa Cargo | |

| Regional Express Americas | Planned for 2019/ATRs | Colombia | 100% | ||

| Brand licenced to but no ownership interest: | |||||

| Avianca Brasil | Oceanair | Brazil's 4th largest airline | Brazil | 0%* | |

| Avianca Argentina | Macair Jet | Regional/ATR72s | Argentina | 0%* | |

Note: * 100% owned by Brazil's Synergy Group, majority owner of Avianca Holdings. Source: Avianca Holdings filings and other sources

| Lessor | A318 | A319 | A320 | A320neo | A330-200 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus Asset Management | 9 | 9 | ||||

| Aircastle | 10 | 1 | 11 | |||

| Aviation Capital Group | 1 | 8 | 9 | |||

| Avolon | 1 | 1 | ||||

| BOC Aviation | 2 | 2 | ||||

| CDB Aviation Lease Finance | 1 | 1 | ||||

| GECAS | 1 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Infinity Aviation Capital | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Jackson Square Aviation | 1 | 1 | ||||

| MCAP/MC Aviation Partners | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Total aircraft | 9 | 2 | 24 | 12 | 3 | 50 |

Source: Flightglobal (December 10, 2018)

| Owned/Finance Lease | Operating lease | Total Fleet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A318 | 10 | 10 | |

| A319 | 23 | 4 | 27 |

| A320 | 35 | 26 | 61 |

| A320neo | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| A321 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| A321neo | 2 | 2 | |

| A330 | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| A330F | 6 | 6 | |

| A300F-B4F | 5 | 5 | |

| 787-8 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| ATR42 | 2 | 2 | |

| ATR72 | 15 | 15 | |

| 767F | 2 | 2 | |

| Cessna Grand Caravan | 13 | 13 | |

| E190 | 10 | 10 | |

| Total fleet | 142 | 54 | 196* |

Source: Avianca Holdings quarterly report 22 Feb 2018.

Note: The filings for Q4 2018 listed the following orders: 124 A320neo family aircraft (del. 2019-2025) and three 787-9s (del. In 2019), plus nine 787-9 options.

* Includes 6 aircraft leased out, of which 4 to Avianca Brasil (two A319s, one A330F, one A330) and two E190s to Aeroliteral SA.

Note: Forecasts by Bradesco BBI (Dec 3, 2018)

Source: Avianca Holdings annual reports

Note: equidistant map projection based on Bogotá, great circle routes appear as straight lines. Thickness of lines directly related to annual number of seats.

* Principal subsidiaries; excludes regional airlines and numerous other small subsidiaries.

Source: Avianca Holdings 2017 annual report filing (May 2018).