Can Saudia compete with the super-connectors?

Jan/Feb 2018

The Saudi state is eying a medium-term IPO of Saudia once the flag carrier returns to profitability and somehow becomes a competitor to the three Gulf Super-connectors — but is this plan far too ambitious for an airline based in one of the most conservative regimes in the Middle East?

The Saudi Arabian flag carrier’s history dates to 1945, with the donation of a Dakota to King Abdul Aziz from President Roosevelt. Fully owned by the Saudi state and known as Saudi Arabian Airlines or Saudia in different periods of its life, it is now called Saudia following the latest rebrand, carried out in 2012.

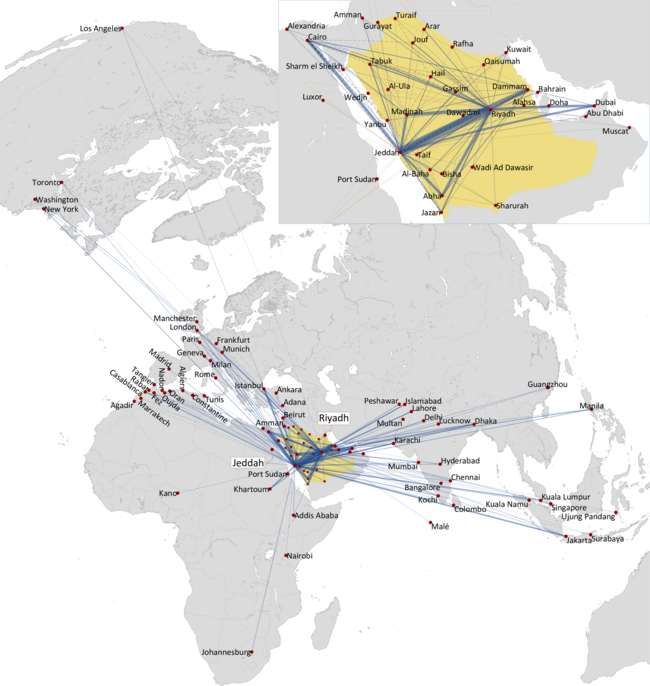

Saudia’s main base is at King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah, with secondary hubs in operation at King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh, King Fahd International Airport in Dammam and Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz Airport in Medina.

The Saudia group employs around 17,000 and operates to 27 domestic and 70 international destinations, the latter comprising 12 in the Middle East, 15 in Africa, 15 across the Indian sub-continent, 10 in the Asia-Pacific region (China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore), 14 in Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK), and four in the US and Canada.

Few financials are available for Saudia, though it is believed to be heavily loss-making. In November last year, Saleh bin Nasser al-Jasser — director-general of Saudia — said it made a profit in the third quarter of 2017 and expects to return to annual profitability in 2019, which is a year earlier than it previously expected.

In 2016, Saudia capacity grew by 10.6%, to 80.3bn ASKs, considerably ahead of a 6.3% rise in RPKs, to 57.1bn. As a result, passenger load factor fell by 2.9 percentage points, to 71.1%. In 2017 passengers carried grew by 8% to 32.2m, carried on 119,000 domestic and 78,000 international flights.

Strategic goals

In 2015 the Saudia group launched a medium-term transformation strategy called the “SV2020 Strategic Plan”, designed to make the carrier more efficient by selling off some businesses (such as medical services and flight training), transforming the fleet and refreshing its services and products.

Among the targets is a mainline fleet of up to 200 aircraft by 2020. The group fleet currently totals 178, and the mainline comprises 159 aircraft, including 44 A320s, 15 A321s, six A330-200s, 32 A330-300s (the last of an order for 20 A330-300Rs placed in 2015 was received in December 2017), nine 777-200s (with an average age of 18 years), 35 777-300s (all delivered since 2012, with five arriving in 2017), seven 747-400s and 11 787-9s (which were all delivered in 2016-18).

28 new aircraft joined the fleet in 2016 and 32 in 2017, and this has fuelled expansion of the network. Last year Saudia launched five new international routes, including Riyadh-Manchester in June and a route to Mauritius in September, while a twice-daily route between Jeddah and Baghdad was launched in October — its first service to Iraq for 27 years, after services were stopped following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. In the summer 2017 season (June to September) Saudia boosted capacity by 20% compared with 2016, and this year more seasonal routes to Europe will be added.

Currently there are no outstanding firm orders — although Saudia may place a widebody order sometime this year, it is believed.

Saudia also operates a 11-strong dedicated cargo fleet, comprising seven 747 cargo variants and four 777Fs (with an average age of three years). Three more 747 cargo aircraft are currently in storage. The group also includes Saudia Albayraq, a specialist VIP business flight operator between Jeddah and Riyadh, which uses three leased A319s (with an average age of 17 years)

LCC move

As part of SV2020, in April 2016 Saudia announced the launch of flyadeal, an LCC based at Jeddah airport. According to Arab Air Carriers Organization (AACO) data, the LCC share of the total Arabian aviation market rose from 5% in 2006 to 22% in 2016, and the Saudi group was very late to look at the business model.

Nevertheless, flyadeal began operating in September 2017 and today flies between six domestic destinations with a fleet of five A320s. With a classic LCC operating model, flyadeal is targeted at leisure, business and Hajj/Umrah pilgrim travellers, and Saudia executives have stated that flyadeal is likely to place an order for 30 narrowbodies with Airbus or Boeing before the end of 2018, with the company making an internal decision by the second quarter of 2018.

However, flyadeal now faces plenty of competition from Saudi airlines. Saudia had a complete monopoly as the only airline based in the country until 2007, when two new airlines obtained government licenses.

The main domestic competitor to the Saudia group today is flynas, which launched in 2007 as Nas Air before changing its name to flynas in November 2013. It’s owned by two Saudi conglomerates and its marketing tag is “The Kingdom’s First Low-Cost Airline”. With hubs at Jeddah and Riyadh, flynas operates to 17 destinations domestically and 17 internationally (in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait, Sudan, Nigeria and the UAE), while a codeshare with Etihad (first signed in 2012) expands its network considerably.

It carried 6.3m passengers in 2016 (a 14% rise year-on-year) with a fleet of 26 A320s, two A319s and a single 767, which have an average age of 11 years. However, under the leadership of CEO Paul Byrne (appointed in November 2014) the airline is pursuing aggressive expansion, and in January 2017 flynas ordered 80 A320neos (plus options for another 40 aircraft) — at a list value of $8.6bn — for delivery over 2018 to 2026.

Another competitor is SaudiGulf Airlines, owned by a consortium of Saudi companies and launched in October 2016. It operates four A320s between its main base — Dammam — and three domestic destinations. SaudiGulf targeted 700,000 passengers carried in 2017 and has ambitious plans to increase its fleet to 30 aircraft within the next three years. Last year its chief executive said the airline would order up to 16 777s before the end of 2017 (for delivery from 2020 onwards), which would enable the airline to launch international routes to Asia, Europe and North America. However, those orders haven’t yet materialised. SaudiGulf also has 16 Bombardier CS300s on order, though delivery has been delayed and there is the possibility that the entire order may be scrapped.

The other Saudi scheduled carrier is Nesma Airlines — based in Jeddah and which operates to 14 domestic destinations, and Cairo, with seven Airbus A320 family aircraft and three ATR 72-600s.

That growing domestic competition is a challenge to the Saudia group. As can be seen in the chart, Saudi Arabia leads the Middle East in terms of scheduled passengers, and this is due largely to its large domestic aviation market in a country that contains 830,000 square miles — substantially larger than any other Gulf nations. The country also benefits from the massive pilgrim market; last year Saudia carried 0.5m pilgrims between 100 destinations on the annual Hajj, on virtually all its scheduled routes plus several charter destinations. The Saudi government also has a plan to increase the number of travellers coming from abroad for the Umrah pilgrimage (in contrast to Hajj, one that that can be undertaken at any time of the year) from 6m in 2015 to 15m in 2020.

But as large as it is, the domestic market or even intra-Arabian pilgrim traffic isn’t the main prize that Saudia is eyeing; what it really wants to do is become an airline that can truly compete with the three Gulf super-connectors.

Saudi politics

Saudia’s long-term strategic ambitions are inextricably tied with those of the Saudi Arabian state.

With the second-largest reserves of oil in the world (after Venezuela), Saudi Arabia has the largest economy of any Arab country. However, GDP per capita has fallen steadily since the oil peak of the early 1980s, and today Saudi Arabia lags the UAE, Kuwait and Qatar in this measure.

That’s partly because Saudi Arabia is the least diversified economy among the Gulf states and is still heavily dependent on the oil sector (it accounts for between 40%-50% of total GDP, depending on which data source you believe) — and hence is vulnerable to fluctuating oil prices. To make matters worse, Saudi Arabia’s proven oil reserves have changed little since 1988, and some analysts believe the country is significantly exaggerating the reserves it has declared.

The economy slipped into recession in 2017 (thanks to low oil prices) and — perhaps more importantly — there is growing unease about the lack of political freedom in a country where most of the population are millennials. In addition, of the 33.3m who live in Saudia Arabia, 8.4m are non-nationals (the majority of which are poorly-paid migrant workers).

The Kingdom is renowned within the Gulf states as having relatively few political freedoms. It’s an absolute monarchy, with no political parties or national elections, and in effect is ruled feudally by the Saud royal family, heavily influenced by the puritanical Wahhabi form of Islam.

The Arab Spring didn’t touch Saudi Arabia, and any political reform since then (such as last year’s decree to allow women to drive) has been marginal at best; for example, it remains one of the few countries in the world not to accept the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But pressure is slowly growing from the young, urban population for change, and the Sauds realise that economic improvements (and diversification) is one way to head off calls for political reform.

Against that background, it’s no wonder that Saudi Arabia has unveiled many plans to diversify the economy over the years. The latest is “Vision 2030”, launched in 2016 with several objectives that include “transforming our unique strategic location into a global hub connecting three continents — Asia, Europe and Africa”.

A futile challenge?

This includes heavy investment in airport and aviation infrastructure, which will help Saudia realise its own ambitious of strong growth in its fleet and network combined. But growth is one thing; it is an entirely different challenge for Saudia to grow and effectively challenge the Gulf super-connectors.

The scale of the task is shown by looking at airport data (which includes transit passengers) — see chart. The five hubs that Saudia operates are largely second-class citizens compared with the hubs of the Gulf super-connectors, with only Jeddah preventing a complete Top Three dominance of Doha, Dubai and Abu Dhabi. And, of course, Jeddah’s passenger flows are boosted considerably by being the closest airport to Mecca (100km), with many of the annual Hajj pilgrims passing through a dedicated Hajj Terminal that can handle 80,000 passengers at the same time thanks to its 5m square feet size.

But Jeddah’s passenger growth was a measly 0.7% in 2017, significantly less than its three super-connector hub rivals, and that’s because the airport is operating at capacity. Huge effort and investment is being made to expand the airport — a first phase that started in 2006 was completed last year (taking capacity to 30m), and the second phase will increase this to 43m annually by 2025, before a final phase will see capacity rising to 80m a year in 2035.

Yet increased capacity does not mean increased connecting traffic. In reality, Jeddah is no better or worse geographically than the super-connector hubs, but Saudia has a long way to go before it can match the appeal of its rivals. The fleets and connection offered by Etihad, Emirates and Qatar far exceed anything offered by Saudia and its hub — and to attract large amounts of west-east and east-west traffic flow Saudia must improve its service standards significantly.

Though Saudia was given the “most improved airline of the year” award by Skytrax at the Paris air show last year, that’s partly because Saudia starts from a very low base. Of course, Saudia is frantically trying to improve its standards and appeal to non-Arabic travellers. It joined the SkyTeam alliance in May 2012 and improved its in-flight entertainment services in 2017 by adding a selection of “Western” movies in 2017 after agreeing a deal with Warner and Fox to supplement its traditional programming (largely religious and Arabian content) and widen the appeal to non-Middle Eastern passengers.

The largely unspoken problem with Saudia is that it still has a severe image problem in terms of being associated with one of the most conservative regimes in the Middle East. And Saudia didn’t help its cause in August last year when it warned it would kick off its aircraft any passenger who didn’t adhere to the country’s strict dress code, which forbids women to expose arms or legs. Its statement also said that women who wear “too thin or too tight clothes” would also be deplaned “at any point”.

With that kind of message going into the market, it will be very difficult for Saudia to become a true competitor to the Gulf super-connectors any time soon — and certainly not by 2020 or 2021, when the Saudi state is planning a joint IPO of Saudia and flyadeal as part of its goal of raising $300bn by selling government stakes in companies over the next few years.

| In service | On Order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | Saudia | flyadeal | ||

| Passenger | 747-400 | 7 | ||

| 777-200 | 12 | |||

| 777-300 | 35 | |||

| 787-8 | 1 | |||

| 787-9 | 11 | 2 | ||

| A319 | 2 | |||

| A320 | 41 | 5 | 19 | |

| A321 | 15 | |||

| A330-200 | 7 | |||

| A330-300 | 32 | |||

| Total | 162 | 5 | 22 | |

| Freight | 747-400F | 9 | ||

| 747-8F | 2 | |||

| 777-200F | 4 | |||

| Total | 15 | |||

| Total Fleet | 177 | 5 | 22 | |

Source: AACO

Source: AACO. Note international and domestic