Air Astana: Kazakhstan's remarkably successful airline

Jan/Feb 2015

Air Astana is a relatively small, 3.8m passengers in 2014, but remarkably successful airline based at Almaty and Astana, the two main cities of Kazakhstan, a country roughly the same size of Western Europe but with a population of only 16m

The airline has little apparent Soviet heritage, being jointly owned by Samruk Kazyna , Kazakhstan’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, with 51% and BAE Systems, the British defence company , with 49%, the side-result of a national radar project in 2000 (that project never materialised but the airline did, under Sir Richard Evans, the BAE Chairman, who seconded BAE executives to Almaty). The country itself is a presidential republic, although President Nursultan Nazarbayev has been in power for the last twenty years and could be described as moderate authoritarian, strongly committed to economic liberalism but with firm political control. One of the fastest growing economies in the world throughout the 2000s, Kazakhstan remains largely dependent on oil, mining and agriculture, although the financial sector has also been expanded. The sovereign wealth fund currently holds over $100bn of assets.

Air Astana’s culture is multinational reflecting the ethnic make-up of the country — a mixture of Kazakhs, Russians, Uzbeks and numerous other minorities. Top management is drawn from various European and Asian backgrounds, though the dominant influence is that of Cathay Pacific. Peter Foster, president and CEO since 2005, is ex-Cathay.

Peter Foster emphasises Kazakhstan’s divergence from Russia. Whereas Russia is turning inwards and backwards to a command economy, Kazakhstan is continuing to implement a raft of liberal legislation relating to property and legal rights and to building up a skilled, enterprise-orientated administration — “there is no plan B.” In contrast to Russia, Kazakhstan now has no visa requirement for visitors from the USA, UK, Germany, France, the UAE and five other major countries.

The company has a proactive approach to hiring local managers, usually selecting young, inexperienced but Western-educated types who can be inculcated with the Air Astana culture ( a bit like the John Swire approach). The Kazakhstan government runs the “Bolashak” programme which sends students to foreign universities, mostly in the US and the UK, on government scholarships.

Air Astana operates an all-Western fleet and has an excellent safety record, but has suffered from the inadequacies of the national aviation authority. In 2009 the Civil Aviation Committee failed an audit by ICAO, resulting in a ban on Kazakhstan airlines by the EU; Air Astana was exempted because of its record but was restricted from adding new capacity to Europe. This led to the ludicrous situation whereby Air Astana was unable to upgrade its service by scheduled its new 757s and 767s on European routes. In April 2014 this restriction was finally removed, with the influence of Tony Tyler, IATA Secretary General and ex-CEO of Cathy Pacific perhaps being significant.

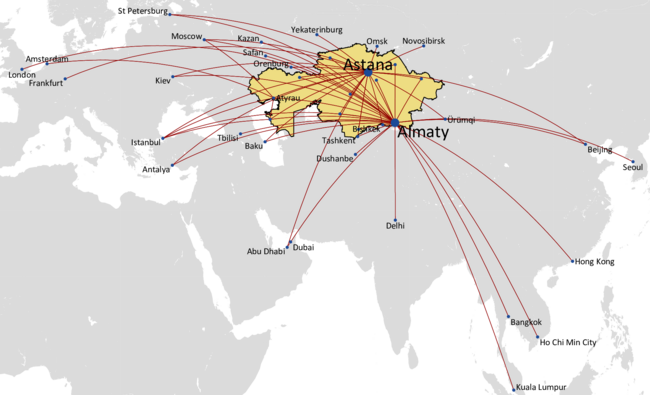

The Air Astana model is fairly unique, neither a network carrier nor having any of the characteristics associated with an LCC. It is a full service airline (on board service is very good, the opposite of the ex-Soviet archetype), with an award-wining Business class (four stars according to Skytrax). It is essentially point-to-point with very little connecting traffic at its hubs (though that strategy is being modified — see below). It flies to 60 destinations from its main hubs at Almaty and Astana and secondary Caspian Sea hub at Atyrau, a network which consists of long thin routes and very long thin routes — the average stage length is over 2,000km.

The fleet is designed to match aircraft capacity to low frequency demand on these routes. Hence with only 30 aircraft, it has four very different types — 767-300ERs, 757-200s, A320 Family (A319, A320 and A321) and Emb 190LRs. While average aircraft utilisation is high, especially considering the winter operating conditions, at around 12.5 hours/day, load factor is just 64%.

With its Central Asia hubs remote from competing systems and with weak competition from airlines in the surrounding countries and in the domestic market, Air Astana can focus on yield maximisation (though there is government regulation of domestic pricing). The average one-way fare was about $240 in 2014.

Domestic competition comes from the unfortunately named SCAT, which operates 737s and 767s but is excluded from Western European airspace and Bek Air, a F100 operator and, remarkably, a Sukhoi Superjet launch customer. The former national carrier, Air Kazakhstan, has been dormant for the past ten years but plans to re-awaken late this year, flying a fleet of Q400s. Air Astana envisages a feeder role for the new Air Kazakhstan.

The idea of a Central Asian or ex-Soviet open skies, rather than the current bilateral regime, does not appeal to Air Astana, the reason according to Peter Foster being that would mean more unfair subsidised competition. He is particularly annoyed by Russian overflight fees being used to subsidise Aeroflot.

Financial results

Air Astana has been consistently profitable since 2002, and 2014 was for Peter Foster “a superb year”. Preliminary operating results for the year show a profit of $97.7m, an increase of 35% over 2013, the highest in the company’s history, and representing a 10.5% margin on revenues of $932.9m. By contrast net profit fell by 62% to $19.3m

A largely unexpected devaluation of the local currency, the tenge, by 19% in February 2014 had severe repercussions for the airline. US dollar debt was revalued by $49m, contributing to a decrease in net profit from $51.4m in 2013 to $19.3m in 2014. The tenge is pegged against the US dollar but the devaluation was provoked by the rouble’s collapse against the dollar which in turn overvalued the tenge relative to the rouble, undermining Kazakhstan’s competitiveness with its major trading partner. While the debt revaluation could be described as a paper transaction there is a serious underlying problem for the airline as the majority of its costs, notably fuel and finance lease charges are dollar-related whereas most of its revenues are in the local currency.

In this respect the operating profit was a very impressive result, reflecting well on the flexibility of the company. The plan was to grow ASKs by 13% in 2014 but this was cut back to 3%, with three Russian routes suspended and Ukrainian services cut back. While unit revenues fell by 2%, unit costs were reduced by 8%. This was partly due to the introduction of two 767s with 6% lower unit operating costs than 757s, the scheduled renegotiation of three A320 leases and the contracts in place with Kasakh fuel refineries.

Some 70% of Air Astana’s fuel is sourced locally at tenge-contracted prices. Last year the refineries took the hit when, following the depreciation against the dollar, the price of fuel shot up. This year, with the collapse in the oil price should have a significant direct benefit for the airline although 50% of the foreign uplift (15% of the airline total) is hedged at $75-85/bbl (current price is around $55), and it is not clear how much the price of contracted local tenge-denominated supplies will fall in response to lower international dollar-priced oil.

Moreover, Kazakhstan is to a large extent an oil economy, and the impact of the oil price collapse is threatening its short-term prospects. Late last year the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) downgraded its 2015 GDP forecast from 5% to 1.5%. Russia is lurching into a severe recession, with the oil price collapse being compounded by Western sanctions over Ukraine — GDP this year is likely to fall by more than 5%. Russia accounts for 25% of Air Astana’s international traffic, but the hope is that the recession there will increase Air Astana’s competitive and service advantage over Aeroflot and Transaero.

Another tenge devaluation is likely soon. On the futures markets the 6-month forward contract is currently trading at over 225 tenge per US dollar — almost 40 tenge above the official fluctuation corridor of 170 to 188 tenge per US dollar. Azerbaijan, another oil-based economy, has decided to abandon its currency peg to the dollar.

Growth plans and connecting strategy

Following the 2014 retrenchment the plan is to resume traffic growth at about 7% a year (see chart) with a surge in 2017 when Expo 2017 will be stage at Astana, attracting an expected 2-3m visitors. However, given the probability of a tenge devaluation and the difficult economic conditions 2015 may also prove to be a low growth year.

The major new destination planned for 2015 is Paris, with Tokyo slated for 2016, probably in a joint venture with ANA. Korea is a substantial growth market, and new services will be added from Astana to Seoul in a joint venture with Asiana. The Kazakhstan-China bilateral is being renegotiated this year which should open up Shanghai and Chengdu in addition to the current service to Beijing.

While remaining essentially a point-to-point airline, Air Astana has been developing its transfer business. As the chart below shows international-to-international connections have been growing steadily and now account for 13% of the international total.

The idea is to add passengers without adding capacity — with a 64% load factor there should be plenty of scope — and also to avoid the complexity that comes with network operations. There are three connecting markets:

Regional-regional This is by far the most important market connecting underserved neighbouring countries and one in which Air Astana has a strong competitive position. Typical city-pairs Bishkek-Dushanbe, Omsk-Tashkent, Moscow-Delhi.

Regional-Intercontinental Air Astana has the potential of leveraging its Astana hub on routes like Urumqi-Frankfurt. Urumqi is a new Chinese mega-city, located 1-2 hours flying time from Almaty and Astana, with a rapidly growing population, estimated at anywhere between four and six million (so about a third the population of Kazakhstan)

Intercontinental to Intercontinental For example, London-Bangkok: basically Air Astana doesn’t even try to compete with the Super-Connectors, but “takes orders” if they happen.

Air Astana is also developing a stop-over product — connecting passengers buy a package which gives them a connecting flight and one or two-day vacation in Almaty or Astana. This is small scale — Cathay did the same thing at Hong Kong in the 1990s — but it is good marketing for the country.

Almaty vs Astana airports

Astana since 1998 has been the capital of Kazakhstan, fast-growing, population of 0.8m, with a. Russian majority, the “Dubai of the Steppes”; Almaty used to be the capital, is larger, with a population of 1.1m, a Kazakh majority and a deep cultural heritage. The climate is less extreme in Almaty compared to Astana, one reason the Almatyans seem to resent the decision by President Nazarbayev, based on “32 objective criteria”, to redesignate the capital

Air Astana’s relationship with Almaty airport, its primary base, has not been easy. The facilities are cramped and tired, and connecting there is difficult. Moreover, there are no plans by the airport owners to improve the situation unless forced to do so. That is a possibility as Almaty is shortlisted with Beijing for the 2022 Winter Olympics, and if Almaty wins it will be obliged to upgrade the airport.

As Peter Foster puts it, “the network will follow the airport facilities”, and, as Astana airport, has announce plans to double capacity to 12m passengers ay era, the growth is going to be concentrated at that airport.

Fleet plans and financing

Air Astana is due to finalise a $800m refleeting plan this year, the financing of which may have become more problematic in the light of the currency weakness.

Two 737-800s are now scheduled for delivery in 2019 (originally three were expected to be delivered at an earlier date), and a decision will be made on an 11-unit order designed to replace the five 757s and four A321s in the current fleet (although the recently refurbished 757s could also have their service extended). The two candidates are the 737-900MAX and the A321neo (perhaps a launch order for the A321LR).

Air Astana will probably fund the PDPs from internal cashflow and seek ECA or ExIm finance for the aircraft deliveries. However, capex of $800m might strain the airline’s balance sheet; as at the end of 2013 shareholders’ equity totalled $308m while long term debt and finance leases were $383m. Net debt was $300m and cash amounted to $128m.

This raises the question of whether a capital raise might be needed; in fact it almost certainly will be needed given the scale of the investment plans. An IPO is possible but private equity would probably place a greater value on the company, especially because of the attraction of a close link with Samruk Kazyna. Air Astana also has a good dividend record paying out 25-35% of net profits to its two shareholders in recent years. BAE might well consider cashing in on its $8.5m initial investment if the company were to be valued at say ten times operating profit, or $1bn. Etihad has inevitably been mentioned as an investor, but this is very unlikely as it would entail Air Astana giving up its UAE service which because of oil industry links has major strategic importance.

| In service | On 0rder | |

|---|---|---|

| A320/321 | 13 | |

| 757-200 | 5 | |

| 767-300ER | 3 | |

| 787 | 2 | |

| Embraer 190 | 9 | |

| Total | 30 | 2 |

Note: *=Jan-Oct