Economic cycles and new industry outlook

Jan/Feb 2013

Four years on from the collapse of Lehman Bros and the following global recession we are still far from sure of the shape of this cycle. It appears that any hoped for recovery is turning out to be far more gradual, taking far longer, and is still subject to significant risks.

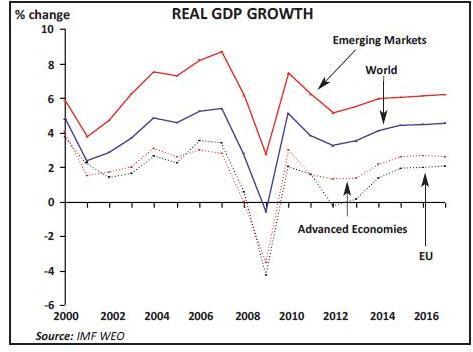

In its latest update to its World Economic Outlook the IMF pointed out that the world’s economy probably grew by 3.2% in real terms in 2012, slightly lower than the 3.9% recorded in 2011 and significantly lower than earlier projections — even if they published the data just before the US announced a fourth quarter contraction in GDP. There remains a significant disparity among regions — with Euroland and the UK in recession; the US growing by a modest 2%; advanced economies showing growth of 1.4% overall; and emerging markets dipping to a 5% rate of growth from above 6% in the previous year.

At the same time the IMF further reduced its forecasts for economic growth over the next two years — on average by 10 basis points — pointing to global real GDP growth of 3.5% and 4.1% in 2013 and 2014 respectively. At least some of the risks that might have been realised have been pushed back a few months: the lemmings in Washington came to a last minute agreement to avoid running over what had become known as the “fiscal cliff”. However, the risks are still there that the US could come to a grinding halt in 2013 if severe austerity measures are introduced; the legislature and executive still have to agree a budget, and will need to remove the ceiling on government debt, to allow the underlying strength of the economy to return.

The Euro Area also continues to add significant risks to the world outlook; the weakness in the “PIGS” periphery seems to be having an increasing spillover to the centre and to other nations; and the Euro crisis is yet far from over. The IMF is forecasting another year of recession (a contraction of around 0.2%) for the Euro Area before a resumption of growth in 2014, although for the EU as a whole is expects growth of the same magnitude this year (helped by a possible 1% growth in the UK).

Among the emerging markets it is also assuming a slight increase in growth rates. Although China’s GDP growth probably dipped to 7.8% in 2012 down from 9.3% in the previous year, the IMF is forecasting a rise of 8.2% and 8.5% in the next two years respectively — one of the few forecasts unchanged from those it made in October last year. Overall emerging markets are expected to grow by around 5.5% to 5.9% in 2013 and 2014 — benefiting from the expected (or hoped-for) recovery in Europe from 2014 — still far from the heady pre-collapse rates of growth.

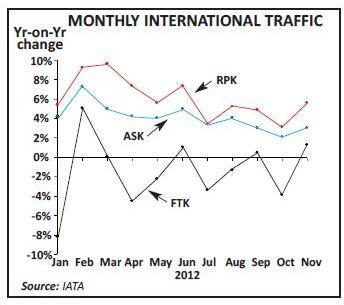

Meanwhile, according to IATA, the airline industry looks as if it will have ended 2012 with passenger demand growth (in RPK) of around 5.3% down from the 5.9% achieved in 2011, while capacity (in ASK) has remained in reasonable control growing by around 4% overall. Through the year, the year on year rates of growth in demand had been slowing — with Economy demand growing faster than Premium demand, reflecting weak business confidence in many areas. Freight demand remains very weak — with a likely 2% decline in total freight tonne kilometres — and IATA points to a continuing shift in freight mode from air to sea.

In December IATA published an update to its financial forecasts for the industry; actually raising its expectations for the outcome for 2012. The industry is being a little more disciplined in its capacity expansion and is successfully recovering through yield growth the step change in fuel costs experienced in the past few years (although it is noticeable that the growth in yields experienced in the first half of 2012 dissipated particularly among the US carriers domestically and on the Atlantic). IATA is assuming a 3% growth in passenger yield in 2012 and a further 5% fall in freight yields.

This has no doubt been helped by distinct declines in establishment of new carriers and the failures of others: the association in its accompanying presentation shows that the number of new entrants fell below 30 worldwide in 2012 from an average of 100-140 a year before the 2008 peak.

IATA is now looking for industry operating profits worldwide of $13.6bn in 2012 (down from $17bn in 2011) and projects profits of $19.2bn for 2013 (compared with its previous forecasts made in September of $9.9bn and $17.3bn for last and this year respectively). The 2013 forecast appears predicated on a 4.5% growth in passenger demand and modest decline in passenger yields, a 1% up-tick in freight demand and a further 1.5% fall in cargo yields along with jet kerosene prices virtually flat at around $1.25/US gallon.

Net profits are projected to come in at $6.7bn and $8.4bn (compared with $8.8bn in 2011 and up from previous forecasts of $4.1bn and $7.5bn). These figures would reflect industry operating margins of 2.1% and 2.9%, and net profit margins of 1% and 1.3%, for 2012 and 2013 respectively. As with the economic data from the IMF, these forecasts point to a slow, gradual (and risky?) recovery.

Meanwhile the third industry cycle — that of the equipment orders and deliveries — are showing continued positive signs. Total industry deliveries in 2012 are likely to have reached 1,295 units up from 1,164 in the prior year. Of these the Boeing / Airbus duopoly accounted for 1,176 units, up from 1,008; the traditional race ended as a dead-heat with each having a 50% share. According to Ed Greenslet’s Airline Monitor this level of deliveries accounted for 6% of the fleet at the year end, slightly below the 6.4% average of the past 20 years. Net orders for the industry as a whole reached 2,551 units down slightly from the 2,830 in 2011, and the order backlog (however valid that measurement really is) according to his figures grew to 10,549 aircraft. This level reflects a possible 8.1 years of production: up slightly from the previous year but still the highest ever.

There have been some well voiced concerns that the industry (ie Airbus and Boeing) have been expanding production capacity too fast and that the projected deliveries over the next few years would start to lead to overcapacity. The Airline Monitor’s base forecasts suggest that the rate of deliveries would run at the rate of 1500-1600 aircraft in the next three years to build to 6.8% of the fleet by 2015. This renewal rate is above the long range average — but as always the difficulties in these forecasts is anticipating the retirement rate; the industry is in general re-evaluating effective economic lives of older equipment in the face of fuel at $100+/bbl. Meanwhile the problems of batteries in the 787, and the subsequent fleet grounding by the FAA, may help to delay actual deliveries in 2013 and prolong the in-service use of older 747s, 777s and 767s.

There are positives and negatives in the outlook as always. There continue to be some significant risks on the downside from the need for fiscal consolidation in the established economies, the continuing Euro-crisis, an intensification of risk-avoidance as banks head for Basel III compliance. There should be some upside as China moves towards a consumption-led economy, and as the immense fiscal stimuli used since 2009 start to work as the central banks want. The airline industry is showing a remarkable discipline in capacity growth that has been allowing yields to recover, even though as a whole the premium markets are not recovering as fast as the leisure markets, while the impact of consolidation in the mature aviation markets may also be aiding constraints on capacity expansion.

In the end 2013 looks to be another year of bumping along the bottom — what is annoyingly becoming known as “the new normal”.