Virgin Atlantic: Isolated in a world of consolidation?

Jan/Feb 2011

In an unusual departure Virgin Atlantic in December announced that it had appointed Deutsche Bank to carry out a strategic “review of the aviation market on its behalf” and (as a seeming non–sequitur) “had received a number of lines of enquiry”. As a private company there would have been no need to rush out a statement in response to press comments — but what better way to suggest that you are putting a company up for sale than get the press interested in potential tie–ups?

The UK media immediately started speculating – with an immediate suggestion of approaches by Delta and/or Emirates expanding rapidly to any airline with (or even without any) cash (even including AirAsia) – culminating in January with an article in the UK’s Sunday Times purporting to suggest in the usual manner of informed weekend gossip that the marriage partner could be Etihad. All the proposed partners have of course denied interest. Meanwhile Singapore Airlines' new CEO Goh Choon Phong has been reported to be relieved to hear that there could at last be an exit potential for SIA’s poorly–performing 49% stake in the UK’s second largest scheduled long–haul carrier – even before he got his legs under his new desk.

Virgin is unique; no other country in Europe has allowed a second home–based long–haul carrier to compete with the flag at its base. But then perhaps London is the only destination in Europe with the quality of direct point–to–point services to be able to support such competition. Since its start–up in 1984 it has tended to target the prime O&D long–haul routes out of London in direct competition with BA and put natural emphasis on the high density and business routes to the US along with high value leisure routes. Eight of its 32 destinations account for 60% of its seat capacity: New York, Orlando, Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Barbados, Las Vegas, San Francisco and Miami. A further six, Johannesburg, Lagos, Sydney, Boston, Dubai and Tokyo account for an further 20%.

The North Atlantic accounted for 50% of total revenues in the year to February 2010 (down from 52% in the previous year) and the Caribbean a further 11%. Virgin Atlantic is a long–haul only airline and lacks short–haul feed – except that provided by code share partners; and it has had a long standing arrangement with British Midland at Heathrow. It relies heavily on UK–based originating traffic with some 60–65% of annual revenues ticketed in the UK. Incidentally it had reportedly had its eyes on acquiring British Midland for some time – or at least developing a more concrete feeder arrangement – although this probably does not quite fit in with Lufthansa’s strategy for its new baby, at least not yet. Virgin meanwhile has consistently avoided joining in with the alliance game, and has so far shunned opportunities for getting into bed with one of the three global alliances; although it is worth noting that of the code share agreements it has signed, the majority of its partners are part of the Star Alliance.

Singapore Airlines bought its 49% stake in 2000 at the tail end of the 1990s wave of airline cross shareholding spree – for what was then thought a stomping £600m – to help boost the balance sheet as Virgin was entering a period of aircraft acquisition; and the original plan for a stock market IPO within three years was scuppered by the events of 2001. It was also perhaps from Virgin’s point of view a rearguard action in anticipation that the British Airways and American Airlines deal would then go ahead, while commentators at the time hunting for a rationale suggested that it might help SIA in developing trans–Atlantic operations (for which it already had traffic rights); although it is still difficult to see what synergies either side could really have extracted from the shareholding. In the end it has taken a further ten years for the BA/AA deal to be permitted by the regulators and the shape of aviation world in the intervening years has changed significantly.

Virgin, and Branson in particular, has unsurprisingly been vociferous in opposition to the proposed ATI and joint venture on the Atlantic between BA and AA for many years. As BA and AA increasingly combine schedules, networks and pricing on the most important long–haul route network for all three carriers, the link up will certainly severely impact Virgin Atlantic’s competitive position.

What are the options? Virgin Atlantic, as a European airline, has to remain substantially owned and operated by European nationals – interpreted by the EU as 51% equity participation. There could be various ways round the legal niceties for a non–EU backer to take an effective majority stake but this could probably only be actively pursued with significant political backing; and the airline’s route rights could even then be endangered. Consequently, a new partner from outside the EU would have to acquire all or a portion of SIA’s stake (and at a price acceptable by SIA), or the Virgin Group would have to maintain its 51% shareholding through new equity issuance. Even then it would still be dubious use of airline equity to take a minority involvement in another airline where control and influence is officially forbidden – and SIA insiders could certainly tell you of the difficulties of trying to influence a majority shareholder.

Of greater potential perhaps would be a partner from within the EU. Virgin already has links with a handful of the many Star Alliance members – and it could well be that Lufthansa may be interested. LH is in the process of trying to turn around the loss making British Midland it was forced to acquire; and a link up between BD and VS at Heathrow may perhaps make a viable network carrier, albeit second fiddle to British Airways as the market leader. However, it is not certain that the Lufthansa board would regard that as a good enough rationale for putting a large amount of cash into an airline, recognising that the second fiddle will automatically forego yield premium to the leader of the orchestra. Air France–KLM may also be a potential partner; the management recognises the distinct market differences that Heathrow presents – particularly on the Atlantic – in contrast to the other disparate European hubs and although it does, with its join venture partner Delta, have a fair share of slots at Europe’s prime international gateway it does not (unlike Lufthansa) have a base carrier there. But it would not be in a position to generate the network feed and it too may not be that inspired at coming head to head with BA on BA’s home ground.

On the other hand it may be difficult to understand why any of the high growth Gulf carriers — or for that matter any US carrier — should be seriously interested in acquiring a stake. Each of the Middle East carriers is concentrating on developing their home bases as new transfer hubs to access flows between the Far East, Europe and Africa; and the only perceivable benefit to Virgin would be long–haul to long–haul transfer which would be as beneficial as the current link with SIA at best. In addition the Gulf carriers are regarded as a serious threat by the two main European network players – and they will do anything in their political power (and they each have a lot of political power) to halt further incursion into what they regard as their natural purview. The natural bidder perhaps in all irony should be the newly created International Airlines Group – although that would be a definite regulatory no–no, even ignoring the history of dirty tricks and whistle–blowing.

Of course in raising these suggestions we are falling into the trap of creating serious conventional errors – and Richard Branson is by no means conventional. In the public statements from Virgin it is important to note that there has not been any suggestion that he would be looking to change the share ownership of Virgin Atlantic – and one should not perhaps read anything into the fact that CEO Steve Ridgway has been elevated to the position of chairman of the AEA. Comments relating to the fact that Virgin Atlantic is the only airline in the Virgin Group in which it retains a majority stake — and therefore one which it would look to sell down — conveniently ignore the ownership rules enshrined in the Chicago Convention. So, speculating that another airline may be interested in buying a stake is possibly based on the false assumption that there really is a willing seller of a majority holding.

Secondly, and possibly more importantly, Virgin Atlantic will look to do what it can from this strategic review as it deems best for the benefit of Virgin Atlantic and the Virgin Group as major shareholder; and should surely only consider a tie–up with another carrier if there were patent and significant synergistic benefits.

Virgin Atlantic in the past has oft spurned the thoughts of joining an alliance for so many years. Perhaps this is fairly based on an underlying feeling that being a junior and small member of a large group dominated by a handful of very large carriers can actually achieve very little in the way of marginal margin improvement beyond that provided by code share and reciprocal FFP agreements (and it already has a plethora of deals with existing Star Alliance members). At the same time the Virgin Group is the only international brand to have created a series of airlines round the world under a truly global brand name (forgetting conveniently the disaster that was Virgin Express – now merged into Brussels Airlines). Perhaps half jokingly, Branson last year stated that he may look to create a fourth global alliance based on the Virgin Group airlines – Virgin Atlantic, Virgin Blue, V Australia and Virgin America – as a counter to the emergence of the BA/AA transatlantic ATI joint venture. The combined route networks would create a semblance of a global network but fall well short of the expanse available to the three others. That move is certainly possible – but he can be no stranger to the idea that the alliances rely on volume to maximise market penetration and that the Virgin Group carriers even combined are relative small beer – between them accounting for only 30 million passengers a year. To counter that he would certainly need to get some more of the non–aligned carriers interested (those that account for the remaining third of world traffic not currently linked to an alliance) – and here it may be worth noting that the fast growing Gulf carriers have notably remained outside the alliance trend.

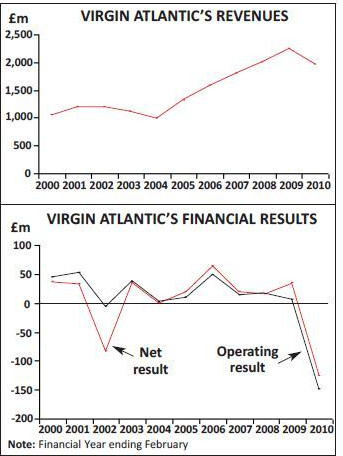

Having said all this, the prime decision will rest with the Virgin Group. As a private company its financial health is obscured from public scrutiny; and as a holding company with minority stakes in a lot of pies, whereas publicly published accounts may seem reasonable on paper, there could always be underlying cashflow difficulties. Virgin Atlantic’s last published results (for the year ended February 2010) are not brilliant – in line with the rest of the industry. In that year, which covered the worst of the recession, revenues fell by 12% to £1.98bn and the airline made an operating loss of £148m (down from an operating profit of £6m in the prior year period) and a net loss of £125m down from a profit of £36m. The balance sheet figures as part of a privately held holding group are meaningless. During 2010 it appears that the airline has been reducing capacity but improving traffic and will no doubt also have been benefiting from the general recovery in yields as premium traffic has returned (and also benefiting strongly from the strike threats at BA). In all fairness a pure guess should be that it would have been able to return to some level of profitability in the current financial year to February 2011.

To put a crude value on Virgin Atlantic: its 3% share of the slots at Heathrow may be worth some £400m; its £2bn revenues should be worth £400m; the brand may have some goodwill value. But SIA paid £600m for its stake in 2000. What is certain is the uncertainty of direction; which is what may actually explain the hiring of Deutsche Bank to provide a strategic review. Virgin sees that it will be squeezed by the granting of ATI to BA and AA, and is possibly right to question its direction and position as a non–aligned carrier in a seemingly increasingly consolidating aviation market.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | ||||

| A330-300 | 10 | |||||

| A340-300 | 6 | |||||

| A340-600 | 19 | |||||

| A380-800/TD> | 6 | 6 | ||||

| 747-400 | 12 | |||||

| 787-9 | 15 | 8 | ||||

| Total | 37 | 31 | 14 | |||