Delta: Will the merger pay off in 2010?

Jan/Feb 2010

The Delta/Northwest merger, which was completed in October 2008, may go down in the history books as the smoothest major airline integration in modern times. But will it help Delta outperform its peers financially?

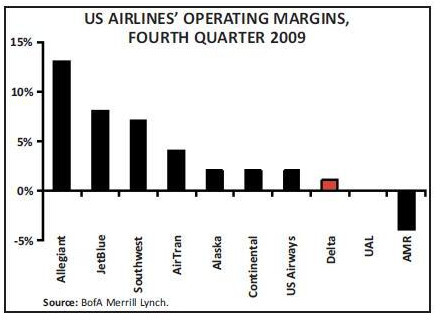

Delta has been slightly ahead of the pack in terms of financial results over the past year or so. It even had a tiny operating profit in 2009 when merger–related expenses were excluded ($83m or 0.3% of revenues), compared with the 0–3% negative margins posted by the other network carriers. But some investors have been disappointed that the gap has not been wider – after all, the combined airline enjoys a cost advantage stemming from Delta and Northwest being the last legacy carriers to restructure in Chapter 11 (both emerged in the spring of 2007).

But things may soon change. The key message that came out of Delta’s annual investor day, held on December 15th in New York, was that Delta is about to start materially outperforming the industry.

The management gave four main reasons. First, given its large size and exposure to international markets and premium traffic, Delta is well positioned to take advantage of economic recovery.

Second, Delta will deliver on merger benefits in 2010. Having secured a single operating certificate from the FAA at year end, the airline expects to complete both operational and technology integration by this spring – something that will unlock many of the revenue and cost synergies.

Third, the merger synergies, network initiatives under way and alliance development will help Delta achieve a RASM premium to the industry.

Fourth, Delta has very modest capital spending plans and expects to generate $6bn free cash flow over the next three years. The lion’s share of that will be used to de–leverage the balance sheet.

This is going to be another challenging year and no major airline anywhere will be adding much capacity. But Delta sent the reassuring message that even when the global economy recovers, it is not going to be flexing its muscle as the world’s largest carrier (by passenger traffic) by resuming aggressive growth. Instead, it will rely on alliances and joint ventures.

Delta’s CEO Richard Anderson stated at the investor day: “Ultimately, this business must evolve towards sustained profitability and a return on capital. That’s what our focus is.” In the longer term, Delta believes that it can earn a sustainable low double–digit (10–12%) operating margin.

But Delta also wants to be recognised as an airline that takes bold action. As Anderson put it: “The unique investment thesis at Delta is that we have been pretty aggressive and pretty creative in getting to that evolved state” (sustained profitability and a return on capital in the future). This was a reference to the merger with Northwest and the rapid implementation of the transatlantic JV with Air France/KLM.

Delta’s attempt to steal JAL from the oneworld alliance and its willingness (if necessary) to invest $1bn–plus in a stake in JAL are further examples of the new aggressive Delta. (As of the end of January, JAL was barely two weeks into its bankruptcy reorganisation and had not yet announced its choice for an alliance partner.)

On track to outperform

Finally, the investor day shed useful light on the Delta–Northwest merger. Detailed reports from the executives overseeing the integration and from labour representatives helped explain how Delta has achieved the seemingly impossible: executing a merger between two large airlines so smoothly, without operational problems and in an employee–friendly way, in a relatively short period of time. Are there lessons that could be applied to other airline mergers? Delta reported a significant $1.1bn net loss before special items (which totalled $169m) on $28bn revenues for 2009. However, the result included $1.4bn of fuel hedge losses resulting from bad hedging decisions in 2008. At market fuel prices, Delta would have earned a $291m net profit before special items in 2009. In other words, the core business was performing.

The robust underlying performance has reflected, first of all, the “best–in–class” cost structure that resulted from Chapter 11. Industry comparisons presented by the airline for the September quarter indicated that Delta’s consolidated ex–fuel CASM was 8–9% below the average for the other network carriers.

Second, Delta managed the recession well. It responded quickly, cut capacity sharply during 2009 and, most importantly, has removed the costs associated with the capacity reductions.

Third, the merger produced $700m in tangible benefits last year (though the $400m revenue benefits in particular were hard to see in the middle of the recession). The merger synergies effectively offset the unit cost pressures resulting from the 6% capacity reduction last year.

On the negative side, Delta felt the full brunt of last year’s economic challenges, especially because of its significant transpacific exposure and heavy reliance on the Japan point–of–sale. Those markets were hit by the double–whammy of recession and H1N1 scares (for some reason Asia–originating travel is always the hardest hit during global crises or pandemics).

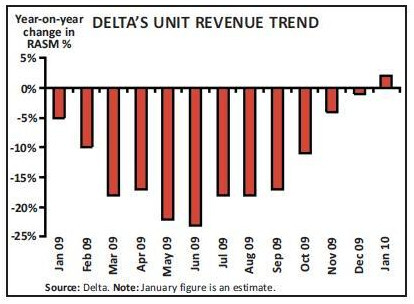

But the upside is that Delta is well–positioned to benefit from economic recovery. When reporting the 4Q results on January 26th, Delta executives echoed their counterparts at other airlines by saying that they had seen clear evidence that a recovery was under way (led by the domestic and transatlantic markets) and that the trends were strengthening into the March quarter. After months of sequential improvement, PRASM turned positive in January (partly reflecting easier year–on–year comparisons). Among the growing evidence that business travellers were returning, corporate account bookings were up by 10% in January.

In mid–December Delta was rather conservatively assuming only 7% growth in passenger revenues in 2010. But the airline expects to generate a healthy RASM premium to the industry, thanks to the merger synergies, a strong rebound on the transatlantic (where Delta’s capacity is down 20%), increased flow traffic from the transatlantic JV and new network initiatives in New York. Delta is also looking to grow its ancillary revenues by $500m or 14% this year.

Delta is currently projecting flat ASMs in 2010, both domestically and internationally. The plan is to offset cost pressures by productivity improvements and cost savings from the merger, keeping ex–fuel unit costs flat this year.

As a result of outperforming on RASM while maintaining its cost advantage, Delta believes that it will be able to grow its profit margin lead over the other US legacy carriers in 2010.

Delivering on merger benefits

The Delta–Northwest integration is now on the home stretch. A quick status report on the three original priorities:

- Consistent customer experience: Most of what the passenger saw on board had been harmonised by April 2009. Aircraft painting continues through 2010. Airport and station integration was 80% completed by June 2009; work on the most complex facilities continued until mid–January.

- Single operating certificate: Obtained on December 31st (exactly on schedule). This will facilitate full operational integration by the spring. Delta will have the first co–mingled cockpits in the coming weeks and a single dispatch system by the end of March. Different Northwest aircraft types will transition to the Delta dispatch system in March–May.

- Technology integration: Delta is on schedule to complete this by the end of March. The loyalty programme cut over was in October 2009. The “crew cut over” (single bidding and tracking system for pilots) was accomplished by year–end. The single reservations and ticketing platform was complete in terms of development work by October, was tested in November–December and will be phased in this quarter.

It will take about two years to get to the full level of the revenue synergies. The merger is projected to produce $2bn in annual run–rate synergies by 2012, while the transition costs will be a relatively modest $600m spread over three years (2009–2011).

The revenue benefits derived so far have come from widebody fleet reallocations in international markets, an expanded JV with Air France/KLM, a new co–branded credit card agreement and renegotiated corporate sales contracts. The cost savings have so far come from the elimination of freighter flying, overhead reductions and scale efficiencies. This year’s target is $600m in new synergies ($350m on the revenue side and $250m cost savings). The revenue benefits will largely result from “unlocking the code” and operating as a single airline in the marketplace. There will be more widebody fleet movements internationally, domestic fleet reallocations, s–curve benefits, the first fully coordinated schedule with Air France/KLM and improved cargo technology. Many of the synergies will be facilitated by a single, upgraded revenue management system, which was in use by mid–December.

On the cost side, the current year will see the full impact of the discontinued freighter flying and new cost savings from single carrier operations, elimination of duplicate IT platforms, improved maintenance programs and renegotiated regional carrier contracts. There will be continued cost savings from airport and station integration and improved vendor terms.

The economic climate drove Delta to eliminate all of Northwest’s dedicated freighter flying (another reason was the advanced age of the 747Fs). All 14 747Fs in the combined fleet had been retired by year–end 2009. This has been one of the key cost–saving moves, as Northwest’s freighter business lost $150m in 2008. Delta believes that it will be able to reaccommodate the bulk of the revenue opportunities while getting the costs out of its system, so the result should be a $150m boost to the bottom line this year.

On the revenue side, Delta will benefit from being able to free–flow the fleet, starting with the April 1st schedule. Until now only limited fleet reallocations were possible because of the constraints of dual technology systems, but the markets in which it was done saw 5% margin improvement. This spring Delta will start moving its domestic fleet around: the A320s will go to the St. Louis hub (for the longer–haul routes to the East Coast) and the MD–90s will go to Minneapolis/St. Paul (for shorter haul missions).

The merger gave Delta an unwieldy fleet of 1,400 aircraft and numerous types, which the airline was basically stuck with because the Chapter 11 processes had already rationalised the fleets and locked aircraft into new lease or financing contracts. So earning more revenue by reallocating the aircraft more effectively across the combined network is important.

Delta began “cross–fleeting” in early 2009 internationally, which basically meant up–sizing aircraft in key markets linking hubs with cities such as London, Paris, Rome and Tokyo. This year will see increased international cross–fleeting, which will boost service in markets such as Atlanta–Paris, Detroit–Frankfurt, JFK–Athens, JFK–Tel Aviv and Memphis–Amsterdam.

Delta executives expect the combined airline to unlock significant s–curve benefits this year. In other words, Delta hopes to gain market share — especially premium traffic and corporate contracts — as a result of having a broader domestic network, more frequencies, strengthened global network and what is now the world’s largest FFP.

The airline expects to gain significant market share in cities such as Indianapolis, where the East Coast/South/Europe/Latin America–focused Delta network meshes well with Northwest’s Midwest/Canada/ Asia–focused network to create “360 schedule strength”. In such cities the combined airline can offer a great value proposition to local businesses, which previously had to use many different airlines. To maximise those benefits, Delta has focused its initial efforts on the top 20 markets where it believes combining the airlines can lead to the greatest increase in market share.

S–curve benefits have lessened with the growth of LCCs, but they can still be important in respect to corporate travel. Renegotiation of corporate contracts has proved very lucrative for Delta: about $100m new future revenue had been generated when the airline was two–thirds of the way through the corporate negotiations.

Why the successful integration?

Of course, the revenue benefits associated with mergers are not necessarily sustainable in the long run because demand is a zero–sum game. But Delta and Northwest have a significant advantage in the initial stages of their union, because there have been no follow–up mergers in the US and because competitors’ alliances will take a while to get into higher gear. If there are lessons from the Delta/Northwest integration that could be applied to future mergers elsewhere, they include at least the following points.

First and foremost, sort out the key issues in advance. The Delta/Northwest plan was unique to the industry in that the joint pilot deal, including agreement on seniority integration, was in place prior to the closing of the merger. It removed one of the biggest hurdles, as pilot seniority has been a difficult issue in previous airline mergers (still unresolved at US Airways/America West, which merged in 2005).

The joint pilot deal, Delta’s mostly nonunion workforce and relatively good labour relations and strong support among Northwest pilots for the contract all contributed to a peaceful integration process.

Another positive was that Delta and Northwest already had some connectivity between their reservations systems through SkyTeam. Labour and reservations systems have in the past accounted for the bulk of merger–related problems.

Another smart move at Delta/Northwest was to sort out the post–merger organisational structure and name the entire executive team well in advance. This enabled the combined airline to retain talent and start capturing merger synergies early.

Airline mergers typically see mainly costs in the initial year or two and revenue benefits kicking in later. The Delta/Northwest plan was designed so that revenue benefits dominated right from the start and the overall merger–related expenses were kept modest. (This design partly reflected the timing of the merger in a weakening economy.)

The Delta/Northwest operational integration has gone smoothly (and operational performance has remained excellent) in part because everything (pilot training,switching to a single dispatch system, etc.) has been done in phases.

With the notoriously challenging IT integration, Delta has had a four–pronged approach. First, it focused on the most critical synergies, particularly the commercial revenue cut overs (call centres, alliances, Delta.com, FFP, revenue management).

Second, in most areas Delta decided that speed was more important than differentiation in driving synergies. It was more important to do things fast than to upgrade systems. One exception was revenue management, where it was felt that upgrading the system at this point would give Delta a major advantage.

New York and Pacific opportunities

Third, Delta focused on simple, disaggregated solutions (where possible) and a phased cut over process, with multiple steps and full–scale “dress rehearsals”, to achieve expedited results and minimise risk. The idea was to avoid the “big bang” type of cut overs, with lots of things changing all at once, that have produced variable results in past airline mergers. Delta has two major network initiatives planned for 2010. One aims to revamp and greatly strengthen the airline’s New York position to “take away any reason not to fly Delta” there. The other is to optimise the value of the Pacific network.

Delta sees New York as one of its biggest opportunities. Having developed a strong international hub operation at JFK over the past decade, the airline now wants to enhance that and build a domestic hub at LaGuardia (the high–yield, preferred airport for New York City travellers). Growth opportunities at the congested LGA are rare, but in August Delta managed to acquire 125 pairs of slots there from US Airways (in a swap that gave US Airways Washington National slots and some route rights).

If approved by the regulators (decisions from the DOT and DOJ are expected in early February), Delta hopes to implement the LGA schedules in June. The deal would double Delta’s size at LGA, making it the airport’s biggest carrier. Delta also claims that it would surpass Continental as the leading airline in terms of ASMs in the New York metropolitan area. Delta would invest $40m at LGA and add service to 30–plus small and medium–sized markets.

The dual–hub New York strategy would work as follows. JFK would focus on international and transcontinental flights. It would retain the feeder markets for international service (in the feeder market channels) and flights longer than 1,400 miles (which are not permitted at LGA). Other flights would be shifted from JFK to LGA, thus freeing slots and facilities for new transcon and international flying at JFK. LGA would focus on New York City O&D traffic and flow traffic between the Northeast and most other US regions; it would have most of the major markets inside the 1,400–mile perimeter that represent about 70% of the US population centres.

After the revamp, Delta’s JFK hub would offer more than 130 destinations, with new services to Stockholm, Copenhagen, Abuja (Nigeria) and Monrovia (Liberia) planned for summer 2010. Delta is also trying to close the gap in terms of the product offering at JFK; it has upgraded its Heathrow service to 767–400s, with flat–bed seats and other amenities, and has introduced its international first class product on the key transcon routes. But Delta still needs to address the issue of its ageing JFK terminal, which compares very unfavourably with the modern state–of–the–art facilities of competitors.

Balance sheet strengthening

The Pacific network, which includes a hub at Tokyo Narita and valuable beyond- Tokyo fifth freedom rights, is one of Delta’s biggest assets. The markets have really suffered, but the longer–term potential is enormous because of the increased feed that the combined airline can offer from almost every major US business centre. To tap that potential, Delta is looking to add new nonstop service to Asia from Detroit and Seattle, expand existing service to resort markets, adjust aircraft gauge to better match capacity with demand and forge alliances. The Chapter 11 restructurings gave Delta and Northwest relatively strong balance sheets, and the merger provided additional cash–raising opportunities. But Delta still had heavy debt maturities looming in 2010- 2011, so its ability to raise $2.1bn when the US capital markets opened to airlines in September 2009 was critical. Those refinancings reduced Delta’s 2010 debt maturities from $3.4bn to $1.5bn. Delta ended 2009 with an ample $5.4bn in unrestricted cash (19% of revenues).

Delta has adopted conservative spending and balance sheet management policies by US legacy carrier standards. Even though it has a relatively old fleet, a much smaller orderbook than its peers and expects to generate $9–10bn operating cash flow in 2010- 2012, it plans only $3–4bn capital spending in that period. The intention is to use most of the resulting $6bn free cash flow to de–leverage the balance sheet. Adjusted net debt is projected to decline from $16.3bn at the end of 2009 to $9.5bn at year–end 2012.

Delta has only four new aircraft deliveries scheduled for 2010 (two 777–200LRs and two 737–800s). With a fleet totalling 1,400 aircraft, the airline feels that it does not need additional new aircraft at this stage (also the fate of Northwest’s order for 18 787s remains uncertain). However, Delta recently agreed to acquire nine MD- 90s for delivery during 2010, calling it a “very cost–effective aircraft for fleet replacement”. The MD–90 is a highly flexible aircraft and its economics are apparently still good at $90 oil.

This will mean only $300m new aircraft capital spending in 2010, compared to the $2.8bn annual average spending in aircraft by Delta and Northwest collectively over the last decade.

But Delta will continue to invest in customer products and productivity–enhancing tools, as well as in airports and clubs. Such non–aircraft investments are expected to add up $1.1bn this year.

There will also be funds available for strategic investments. The $1bn–plus investment in JAL will probably now not happen (see pages 4–5), but back in December Delta executives said that the funds were certainly available because of the $5bn–plus cash balance, strong free cash flow and low aircraft spending needs.

The future: alliances rule

Delta is an enthusiastic proponent of alliances. In his opening comments at the investor day, Anderson argued that, as well as being a solution to international crossborder consolidation issues, immunised JVs will “help this business model evolve to a return on capital”.

Spearheading Delta’s efforts in this area is the transatlantic JV with Air France/KLM, which was signed in May 2009 (after securing antitrust immunity a year earlier) and is now being developed aggressively. The partnership will be deeply integrated, along the principles of the hugely successful Northwest/KLM alliance. This year will see fully coordinated schedules, fully leveraged hubs and beyond networks, single pricing and inventory management, a single offering approach to all corporate and trade accounts (taking advantage of each partner’s point–of–sale presence) and joint revenue management. The partners are working to add Alitalia to the JV. When fully developed, Delta expects the transatlantic JV to boost its bottom line by $200m annually.

Delta has just launched a very interesting code–share and marketing alliance with V Australia and Virgin Blue to complement its new Australia services. But otherwise the future thrust of its alliance–building will be to develop SkyTeam around the world, particularly in Asia. Vietnam Airlines is the latest addition to the Asian portfolio, which also includes Korean Air, China Southern and China Airlines. But the biggest prize would be JAL, which will be deciding in the coming months whether to remain with American/oneworld or switch to Delta/ SkyTeam.