Recovery in the air?

Jan/Feb 2010

A New Year is proverbially the time to turn over a new leaf; and with the arrival of 2010 there are at last some signs that the current deep global recession may be nearing its end.

In its WEO Update in January the IMF, encouraged by stronger than expected data for the second half of last year, raised its projections for world economic growth in 2010 by 0.75% to nearly 4%, accelerating to 4.3% growth in 2011 after an expected 0.8% drop in 2009. The UK has managed to produce initial Q4 figures showing growth after 18 months of recession and the US GDP growth figures for the same period are well above expectations, primarily as a result of an apparent turn in the inventory cycle.

The IMF expects all the major developed countries (with the exception of Spain) to return to growth in the current year from the deepest recession in recent times, noting that the extraordinary fiscal stimulus put in place may have managed to “forestall another great depression”. However, in the same breath it expresses concern that the recovery is uneven. In the developed world it expects growth in 2010 of 2% rising to 2.5% in 2011, albeit expecting the recovery here to be relatively weak by historical standards; output is not anticipated to exceed the pre–crisis levels until the end of 2011 at the earliest – and later for the Eurozone, the UK and Japan.

And as for airlines...

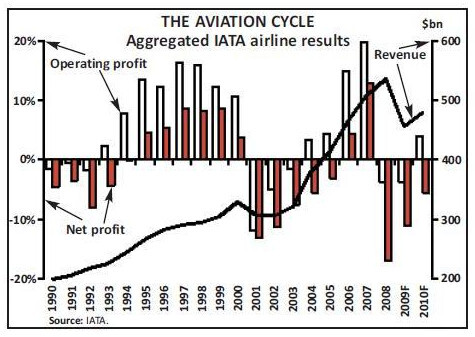

Among the developing nations – expected to grow by 6% this year after a weak 2% in 2009 and accelerating further in 2011 — it sees key emerging economies in Asia leading the global recovery, as a result helping push up demand and prices for commodities despite high inventory levels (notably oil). There are still some major risks: that this rise in commodity prices may stall the recovery (and especially consumer demand) in the developed world; and that the fiscal stimulus – the substantial amounts of cash pushed into the banking system by the central banks – will come to a “premature and incoherent end” amid concerns about the need to repair national budgets. And, of course, the financial markets could get more jitters (such as the news earlier this month that China was restricting bank lending), which would upset confidence. It might be assumed that a resumption of growth should make airlines much happier about the prospects for 2010. However, in its latest prognosis for the economic health of the industry (published in December), IATA does not quite think so yet. The trade organisation’s respected economist Brian Pearce stated that IATA still expects the industry to show operating losses of another $3.7bn (and net losses worldwide of $11bn) for 2009 – a slight improvement on the 2008 numbers of $3.8bn at the operating level (and $16.8bn net, at least before mark–to market losses on fuel hedging among other extraordinary items).

This is on the assumption of an industry- wide fall in passenger traffic of 4%, cargo demand of 13% and drops in yields of 12% and 15% respectively. This would mean total revenues for the industry would have fallen by a massive 15% last year — this compares with the 6% decline in revenues in 2001, the only other year in its history that the industry has suffered a loss in revenues — nearly (but not quite) matched by falls in costs in 2009.

For 2010, however, IATA has increased its estimates of industry–wide net losses to $5.6bn from $3.8bn previously (on the assumption of an operating profit of $4bn). The concern is that although the economic background seems to be improving with a resulting positive outlook for traffic demand, there is an increasing risk of even further downward pressure on yields and upward pressure on fuel prices.

Although the industry managed to cut capacity in 2009, it has continued to take delivery of new aircraft and this has been at the expense of aircraft utilisation (down by around 6% on both widebody and narrow- body fleets last year against early 2008 levels) and we are still about to enter the peak of this aircraft delivery cycle – with another 1,300 units or 5% of the worldwide fleet due to be delivered in 2010 (further delayed delivery re–negotiations and cancellations notwithstanding). IATA also, points out (echoing the more recent IMF release) that world trade volumes (after a possible 15% reduction in 2009) are forecast to rise by rates lacklustre in comparison with previous cycles.

Additionally, premium traffic — the backbone of long–haul traffic and the former strength of intra–European traffic — although rebounding modestly, as evidenced by recent company statistics, is likely to take some time longer to recover to pre–crisis levels (and maybe for other reasons C–class traffic in Europe will disappear entirely).

Following two years of heavy losses and the severely difficult times at the beginning of last year the industry has been cash flow negative for most of 2009: on an industry–wide basis IATA says that operating cash flow generation had fallen to 5% of revenues — a third of the normal levels. With the banking system in disarray many of the normal sources of debt and aircraft finance disappeared and the industry tapped the capital markets deeply — raising a total of $25bn (intriguingly and irrelevantly equivalent to the total market capitalisation of the US quoted airline industry) in 2009 (20% from the equity and 80% from the debt markets), up from $5.8bn in 2008.

However, this capital raising has at least been able to boost cash coffers to reasonable levels (at least for the European carriers) to weather the current off–season – with European and US carriers sitting respectively with 90 and 70 days' cash as a proportion of annual revenues (although the Asian carriers, with only 45 days' cash, appear more vulnerable).

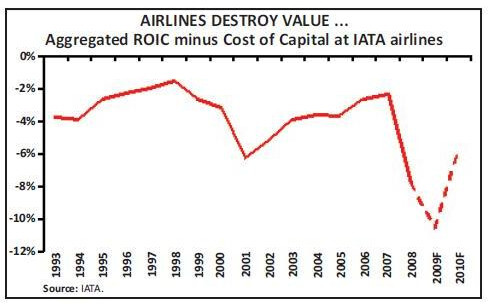

If these prognoses are correct – and they appear reasonable – the global airline industry will end the first decade of the 21st century having lost more than it ever gained since its birth: the industry managed to generate net profits of $39bn between 1945 and 2000, but since then (including restructuring costs and recently mark–to–market fuel hedging profits and losses) has managed to lose $68bn – and during the “noughties” only managed to make profits in three years out of 10.

It is an old adage in the industry that the airline business is an excellent way to make a small fortune, as long as you start with a large one. On the other hand, early investors in Southwest, Ryanair, easyJet, JetBlue AirAsia, Air Arabia and, maybe, Virgin America, have done very well out of the industry.

The IATA December release highlights the record of the industry in creating value – with a series of data showing the industry–wide return on invested capital (ROIC) compared with the estimated weighted average cost of capital (WACC) (see chart, front page). Since 1993 IATA shows that the industry has generated an average return of 4.5% below the cost of its capital, significantly destroying value. Of course this is a global total and masks significant individual performances — but few carriers have been able to be considerably profitable over the years, or at least for a reasonable length of time.

In this new year the world’s economies may appear to have discovered a new leaf to turn over and provide some reasonable hope for recovery. Airlines, however, may have to wait a little longer.