US cautiously expects healthy profits in 2009

Jan/Feb 2009

The collapse of the price of oil in the past six months and the significant domestic capacity cuts since the autumn have meant that the US sector, which posted an aggregate net loss of around $4.4bn for 2008, will turn profitable this year. Outlandish as it sounds in light of the current economic turmoil, the US airline industry could even achieve record profits this year.

A mid–January forecast from JP Morgan floated the prospect of a $10.6bn aggregate operating profit for the sector in 2009, which would be about $3bn higher than the previous annual record. It would mean individual network carriers achieving operating margins in the 6–11.5% range.

The JP Morgan forecast assumes the price of oil averaging $55 per–barrel, industry capacity falling by 5.5% and sector revenues declining by 4.5% this year. The latter would be more than the typical 1–2% revenue declines seen in past recessions but not as severe as the 7–8% fall seen in 2002 in the wake of September 11 (when people were afraid to fly).

At the other extreme, Delta’s management has for some months been predicting that industry revenue could decline by as much as 8- 12% in 2009, while some analysts are currently assuming a 7–8% decline. But, according to JP Morgan, even a 9% revenue decline would still produce a healthy operating profit similar to 2006’s $5.1bn.

The problem is that airlines have little visibility beyond the very near–term to predict demand and revenues. But the macroeconomic doom and gloom has certainly intensified in recent weeks, both globally and in the US. There is a sense that the recession will be more severe than previously thought and that the worst is yet to come in terms of job losses and corporate bankruptcies. And Iata’s monthly statistics have painted a dire picture of international premium traffic and cargo trends.

Anatomy of a financial recovery

Consequently, there is growing concern among investors and analysts about US airlines’ traffic and revenue prospects in 2009. Much of the questioning at the fourth–quarter earnings conference calls in late January focused on that subject. Exactly what trends are the airlines seeing? How much flexibility do they have to respond to any negative developments? Having slashed domestic capacity, are they prepared to do the same internationally? US airlines can look forward to profits in 2009 essentially because of two developments: the collapse of the price of oil in recent months and the industry’s timely and significant collective response last year to the threat posed by $130–plus oil, which included a 12% domestic capacity reduction and lucrative new ancillary revenue streams.

However, the foundations for the recovery were laid in the preceding years, in the aftermath of September 11. The multi–year Chapter 11 restructurings and heavy cost–cutting (in or out of bankruptcy) played a key role in “recalibrating the industry earnings model from $30 oil input to the mid-$80s” (as one analyst put it). Including last year’s actions, it is now estimated that the US airline industry has adapted to the tune of achieving operating break–even at $120 oil – a stunning achievement.

In recent years, attitudes have changed about capacity addition, so the latest cutbacks were not that great a psychological leap. American led the way several years ago with extremely disciplined capacity growth, the idea caught on and there was a period of constrained industry capacity expansion.

Also illustrating the new disciplined approach, many of the US legacies have taken a break from ordering aircraft in the post- September 11 era, if only because they could not justify the acquisitions on an ROI basis. This has meant that the vicious circle of ordering aircraft in good times and taking lots of deliveries when times are bad has been broken.

Oil price collapse

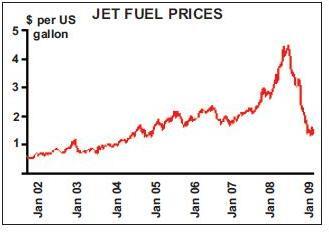

Importantly, US airlines will not be much affected by the credit crisis because they have adequate cash reserves and minimal aircraft funding needs in 2009. The key factor fuelling this year’s financial recovery has been the dramatic decline in the price of oil, from a peak of $147 per barrel in early July to the $40–level as of early February. This has provided enormous cost relief for the airline industry. The decline from last year’s average price of about $100 to $40 would represent a $27bn aggregate cost saving for US airlines in 2009 (based on Merrill Lynch’s earlier estimate that every $1 move in the price of oil swings annual industry profitability by $450m). It would take a 20–25% decline in industry revenues to negate that benefit.

Of course, the sharp decline in oil prices has meant that airlines with sizeable fuel hedges in place have incurred large mark–to market unrealised losses on hedge contracts, as required by accounting rules. Such charges played havoc with financial results in the second half of 2008, even causing Southwest (which has had the industry’s largest fuel hedge position by a wide margin) to report net losses in the past two quarters. Many airlines also saw their cash positions decline due to significant cash collateral posting requirements related to their out–of–money fuel hedges.

The fourth quarter may have represented the worst on the combined fuel cost/hedging loss/cash outflow front for US airlines. Fuel prices were still up significantly year–over–year, and both the mark–to–market losses and cash collateral requirements probably peaked. If oil prices stay at reasonably low levels, US airlines should begin to fully realise the benefits by mid–year, as the expensive fuel hedges expire or are settled.

Several of the airline executives commented in the fourth–quarter calls that the industry again has a natural hedge against declining demand. Continental’s CEO noted that “we are blessed to be in an industry where, as demand has fallen, our single largest expense item, fuel, has fallen materially as well.”

Given that this recession is truly global in nature, with Europe, the US and Japan all being hit hard at the same time, it seems likely that oil prices will not start heading back up anytime soon. But there is always a risk that the oil price/demand relationship does not hold. JP Morgan analysts noted that an unlikely scenario, but one that they feared the most, would be a fuel price spike later this year for some reason other than economic improvement (terrorism, geopolitical upheaval, unprecedented OPEC coordination, etc.).

While some US airlines still have significant fuel hedges in place for 2009, most of the programmes are winding down. Notably, Southwest has reduced its net hedge position to only 10% of its fuel needs each year between 2009 and 2013. That was done by selling swaps against the existing out–of money fuel hedge positions, effectively capping the mark–to–market losses at around $1bn. Southwest paid no additional premiums, avoided having to fork out an additional $500m in cash collateral and will realise the $1bn in losses as future fuel is consumed.

Massive domestic capacity cuts

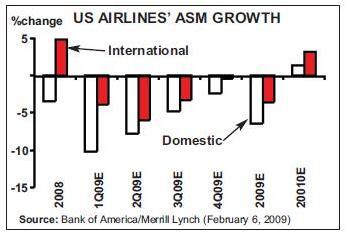

Those airlines that have continued hedging, such as AMR and UAL, are now doing it at a slower pace and using more conservative instruments. Most of the airlines have stressed that they continue to believe in systematic fuel hedging as a way to protect their cost structures and earnings from market volatility and catastrophic price increases. They are ready to jump back in as opportunities arise, but right now is not the time to be long on energy. The second key factor fuelling US airlines’ financial recovery is the massive domestic capacity reduction, which will help airlines maintain pricing traction as demand declines. The cuts, which airlines began announcing in the spring and early summer 2008, resulted in an aggregate 12% domestic ASM reduction in the fourth quarter, with a similar 10%-plus cut implemented in the current quarter. As of mid- January, analysts had pencilled in a 5–7% industry ASM reduction for 2009, though that will increase if economic conditions worsen.

This is the first time that the US airline industry has acted proactively in front of a recession to pare back capacity. In the face of $150 oil (or $200, as Goldman Sachs predicted last spring), the airlines really had no choice. First, because of overcapacity and intense competition in the US, it was not possible to raise fares to come close to matching the increased costs. Second, Chapter 11 was no longer an option. So airlines slashed capacity just as fuel prices plummeted, leaving them well–positioned to face the next challenge: recession.

The current capacity cuts are all the more beneficial because the airlines are now succeeding better in removing the associated costs. Merrill Lynch noted in a late–November report that “the old adage that it was impossible for an airline to shrink to profitability should be discarded”. It made sense in a world where the fixed/variable cost mix was 80%/20%, whereas “today’s 35%/65% split has allowed the industry to cut capacity and costs at the same time”.

Getting rid of costs has been easier because of the large numbers of older, fully–depreciated aircraft in many US carrier fleets. In some instances, whole domestic fleet types are being retired.

Boost from ancillary revenues

Most significantly, all of the LCCs have joined in. Even Southwest is now cutting capacity by 4% in 2009 – its first–ever annual contraction. The airline announced rather dramatically in January that it had suspended indefinitely its fleet growth plans and that it was entering a “no–growth era”. This is an enormous positive for the entire US airline industry in 2009. The third factor helping US airlines this year is ancillary revenues. The spring and summer of 2008 saw the legacies move en masse to increase existing ticketing, change and excess–baggage fees, create new revenue streams by charging for à $1 service such as checked bags and introduce new travel enhancement products such as cabin upgrades. These activities have only limited associated costs and are turning out to be a lucrative revenue source. By some estimates, à $1 activities will boost industry revenues by $3–5bn in 2009.

Because many of the new fees were introduced in May/June, the revenue boost will be the greatest in the first half of this year – just when the airlines may need it the most. Although some of the fees have been modestly scaled back in recent months, airlines say that ancillary revenues appear not to be particularly sensitive to the economy (rather, they are correlated to load factors).

These new pricing models, which were pioneered by European LCCs like Ryanair, appear to have been broadly accepted by the US travelling public. All US airlines have benefited. At one extreme, United, a global carrier with a focus on premium traffic, calls ancillary revenues a “proven and meaningful contributor” to its bottom line, estimated to generate some $1.2bn of revenues this year. US Airways, a primarily domestic carrier with more leisure focus, is on target to realise $400–500m of ancillary revenues this year. And Southwest has also been doing well with a strategy that charges no fees for basic services but sells new premium–type products.

Demand and revenue challenges

US airlines have been eased into this recession more gently than their counterparts in other worlds regions. While airlines elsewhere began reporting sharp premium traffic declines in September or October, US airlines detected a broad weakening in that segment only in the latter half of the fourth quarter, and their total RASM held up well right through the year–end holiday period.

This is mainly because the sharp domestic capacity cuts have really helped limit the financial damage. The domestic market still accounts for the bulk of the US legacies’ operations (though Continental is now 50/50 and Delta about 40% international).

In the fourth quarter, the top four US legacies – Delta (including Northwest), American, United and Continental – saw a combined 7.6% decline in their mainline (domestic and international) ASMs. Traffic fell by 8%, resulting in a slight 0.3–point decline in load factor, which remained at a historically high 79.8%. Because of the extremely constrained capacity, industry RASM improved throughout the period: up 8.8% in October, 0.4% in November and around 5% in December.

January saw continuation of the capacity cuts and a slightly steeper 10% traffic decline, resulting in a 1–2 point fall in load factors. However, the positive unit revenue trend has reversed. Based on some airlines’ reports, in early February the expectation was that industry RASM was down by 4–5% in January.

The negative RASM trend reflects several factors: significantly weaker premium cabin demand, a sharp decline in international bookings and increased fare discounting domestically to cope with some softening of leisure demand.

United, which probably carries more premium traffic than the other legacies, in late January reported seeing a double–digit year–over–year decline in international premium travel. In the fourth quarter, premium cabin demand was off as much as 25%, as some traffic evidently moved to the coach cabin. In January, United’s total international traffic fell by a staggering 15.1%.

Having seen much weakness in business bookings domestically in recent months, in late January Continental was seeing a significant decline of its front–cabin RASM internationally, due to both lower yields and load factor. Many airlines noted that higher coach yields mitigated some of the decline in premium class bookings – another indication that international business passengers are switching to coach.

In terms of forward bookings (typically for up to six weeks), American said in late January that international booked load factors were down nearly 8 points, compared to a 2.5–point decline domestically. Delta reported 7–9 point lower load factors internationally for February and March, compared to 2–4 point declines domestically.

The worst–affected international market is the transatlantic, especially New York–London. United’s London market PRASM fell by 4% in the fourth quarter, contrasting with a 3% PRASM improvement to the rest of Europe. Continental noted that the declines in both the load factor (down six points) and the premium cabin RASM are the worst on the transatlantic, where the back cabin is holding up much better. Continental executives noted that this is a time they are “really grateful to be flying so many 757–200s to Europe” (which have a smaller number of seats allocated to the front cabin than competitors’ aircraft).

Latin America, which has been the brightest spot internationally for US carriers in recent quarters, is performing less well now but still better than the other regions. RASM growth continued to be in the mid–single digits in the fourth quarter, but Continental noted that the load factor is now running 1–2 points behind last year’s.

The Pacific market has exhibited mixed trends. American’s RASM there surged by 11% in the fourth quarter. United saw only a slight overall RASM increase, with Japan remaining strong (up 9%), China surprisingly improving by 2% and South Pacific seeing a double digit decline (Australia was down 20%). United noted steep declines in the premium cabin. Delta/Northwest reported relatively strong performance for its Pacific entity, particularly in the resort and beach markets, which are being helped by the strong yen. But demand to India and the Middle East has been affected by the conflicts in those regions and terrorism concerns.

Like their counterparts in Europe and Asia, US airlines have witnessed sharp declines in international cargo traffic – a lead indicator for the global economy. Freight volumes have been particularly hard hit on the Pacific. Total international freight revenues typically fell by 20–25% in the fourth quarter. American and Continental saw 27% and 23% cargo traffic declines, respectively, in January, which was in line with the 23% fall in international cargo traffic reported by Iata for December.

Domestically, the more business–oriented markets around the country have suffered the most. Delta noted that certain industries like financial services and automotive are significantly weaker, while the aerospace and health care sectors have held up better. As companies continue to trim travel budgets, business customers are making fewer trips, downgrading more to coach class or buying tickets further in advance to take advantage of lower fares.

Leisure demand in the US has remained surprisingly resilient — some airlines have suggested this is because leisure travel has become less discretionary (just something that people do), plus domestic air fares remain cheap and air travel a great bargain. However, since January airlines have been seeing lower yields on leisure bookings – something that US Airways called its biggest disappointment. This is because the industry has started pricing leisure travel more aggressively.

More aggressive fare sales in the near term are probably inevitable and are not a great concern for several reasons. First, continued extremely tight industry capacity is likely to keep a lid on discounting and hence excess yield dilution. Second, yield management systems are now much more sophisticated than in previous recessions, enabling airlines to monitor and make the right trade–off between fares, availability and demand to maximise revenues, on a flight–by–flight, market–by–market and day–by–day basis. This is particularly the case with LCCs, many of which have invested in new yield management systems and strengthened that function considerably in recent years. Southwest’s executives noted (in response to a question in the fourth–quarter call) that the airlines are now “able to discount without destroying RASM”.

In an early–February report, Calyon Securities estimated that February would see US airlines’ traffic decline in the “low–teens” and load factors generally holding up. RASM decline could be similar to January’s mid–single digit fall, as airlines discount selectively to cope with seasonal and economic weakness and passengers trade down to coach class. The shift of Easter from March to April this year will make for a tougher first–quarter comparison – airlines noted that this has historically cost 1–2 load factor points. But Calyon Securities optimistically calls the late Easter a “major kick–off for the heavy summer travel season”.

When commenting on demand in the fourthquarter calls, all of the airlines stressed that it was difficult to draw any meaningful conclusions regarding trends because of a shortened booking curve and extreme volatility. Except for some premium passengers taking advantage of lower fares by booking further in advance, far more people are refraining from making travel decisions until the last minute. Airlines are seeing fewer bookings and March is looking particularly weak, but bookings may build closer in to the actual travel date. US Airways noted that its forward–bookings and revenue data were “significantly more volatile than at any time in the past” and that its ability to forecast revenues was “extremely murky at this point”.

Domestic airlines best-positioned

Of course, the biggest question, shrouded in total uncertainty, is how deep the recession will go, when it will bottom out and how long it will last. The best attitude, expressed by Southwest’s CEO Gary Kelly, is that “our outlook must be cautious given the recessionary environment”. Regardless of how the economy will turn out, it seems likely that the US domestic market will outperform the international market on the revenue front this year, reversing the trend seen in the last few years. This would mean that primarily domestic carriers like US Airways, Southwest and JetBlue are best–positioned in the short term.

This is a particularly welcome development for US Airways, which had a difficult 2008 and saw its unrestricted cash position dwindle to just 10% of annual revenues at year–end (though, it must be stressed, there are no real liquidity concerns). In addition to gaining from the domestic pricing environment, US Airways can expect to record the biggest ancillary revenue gains (80% domestic exposure; most international tickets remain “bundled”). It has less exposure to the international cargo market, which is really suffering. And it could benefit the most from Southwest’s historic capacity cuts since its network has more overlap with Southwest than anybody else.

Although Southwest faces some new challenges – among them maintaining its cost structure and employee morale during a period of contraction – it has historically always outperformed the industry in recessionary times. Southwest has made good scheduling adjustments over the past year, focusing growth in a few key markets and enhancing the overall profitability of its network. It has enhanced its revenue management capabilities. It is expected to benefit from a 15% reduction in competitive capacity in its markets in the first half of this year.

Thanks to new product and revenue initiatives rolled out last year, Southwest’s brand is probably stronger than ever. This was indicated by its 9% RASM improvement in the fourth quarter, which was twice as high as the 4.5% mainline domestic RASM increase recorded by the legacies, even though Southwest’s capacity was up by 0.8% and the legacies’ was down by 12%. As of late last month, Southwest was expecting a 7% RASM improvement in January. Even though the airline mentioned “notable softness” in its post–January bookings, it also noted that measuring any impact was tough since its booking curve was so short.

More international cuts?

LCCs like JetBlue and AirTran may find that their shorter–haul international routes to the Caribbean will be significantly more recession–resistant than the legacies’ long–haul international services. When money is tight and the economy uncertain, people tend to opt for shorter–haul vacation travel. Alarming near–term demand and revenue trends, lack of visibility beyond 6–8 weeks, tremendous uncertainty about the global economy and the need to remain cautious – how does all that play out into the decision–making about international capacity plans in 2009?

The short answer is that at this point US airlines are not planning additional international service reductions, but they are watching trends very closely and are prepared to act if recession proves worse.

The initial rounds of cuts last year saw some trimming of international ASM growth rates and elimination of some marginal European and Asian routes, effective in the fourth quarter or in 2009, as well as one–year delays to new China service launch by United, Northwest, US Airways and American. Recent months have seen further actions, including a significant trimming of international winter schedules by Delta/Northwest following the completion of their merger. In January, American announced that it would take advantage Boeing delivery delays to further modestly trim its capacity this year: it will not use MD–80s to backfill flying associated with seven 737s whose deliveries were delayed from 2009 to 2010.

US legacies’ international capacity is currently expected to decline by about 3% in 2009. This is about half of their planned domestic contraction rate.

The Delta/Northwest combine has effectively put on hold its earlier ambitious growth plans and is currently looking at a 3–5% international capacity reduction in 2009. In January the airline terminated its Seattle–Heathrow, Detroit–Frankfurt and second daily Atlanta–Gatwick services, and the JFK–Heathrow morning flight will be axed in April. Planned new routes to China, Paris, Tel Aviv and Gothenburg have been delayed, though Detroit–Shanghai and Seattle- Beijing are currently still due to start in June (with reduced frequencies).

Delta is committed to capacity discipline and has significant flexibility to ground more aircraft if necessary. At the same time, the airline believes that its expected $6.5bn in merger synergies and cost savings in 2009 and its size make it well–positioned to compete globally.

Having announced the modest further cuts in January, American stated in early February that it was holding off from any further capacity reductions. The airline grew international service much less aggressively than its competitors last year. Its international capacity is currently slated to fall by 2.5% this year.

As in the domestic market, United has the most aggressive international capacity cuts in place for this year, with ASMs slated to decline by 5–6%. The airline is on track to complete the removal of 100 aircraft from its fleet by the end of this year, including all of its 737s and six 747s.

United is also reducing the number of first and business class seats on its 767s, 777s and 747s by 20%, which will help offset some of the effects of the premium traffic decline. The process began in late 2007 and will be completed in late 2010.

United is understandably determined to preserve the breadth and relevance of its global network. While cutting back in many markets, the airline is going ahead with the launch of its nonstop Washington–Moscow service in March (with the reconfigured 767s), after starting Washington–Dubai in October 2008.

Likewise, Continental is going ahead with the launch of a daily Newark–Shanghai service in March. This long flight will boost system ASMs by about 2%, meaning that Continental’s international capacity is currently expected to decline by only 1–2% this year. The decision has raised a few eyebrows, but the route is an important part of Continental’s long–term strategy and the airline clearly feels that it can be viable. Continental executives noted in the recent conference call that the international business is “still solid, just less profitable than it used to be” and that long–haul flights have benefited disproportionately from the fuel price collapse.

While Continental also hopes to launch new routes such as Houston–Frankfurt and Houston–Rio this year, the airline expects to reduce capacity further in several markets through frequency reductions, aircraft downgrades, day–of–week reductions, seasonal reductions or market exits.

US Airways still expects to grow its international capacity by 10% in 2009, because it is behind competitors in international operations. This year’s planned new services include Philadelphia–Tel Aviv and new transatlantic routes to Birmingham, Oslo and Paris. The airline has applied for Charlotte–Rio, which would be its first route to South America. But US Airways is also considering frequency reductions on certain under–performing European routes.

Investing for the long term

Of course, international routes plans are increasingly tied to alliances – probably the least risky way to venture into new markets during a global recession. For example, American hopes to operate Dallas–Madrid from May – on the expectation that its oneworld JV and ATI applications will be approved. United plans to operate Washington–Madrid as part of an extended partnership with Aer Lingus (which will supply the A330s). In recent months many of the US airlines have made the (perhaps obvious) point that while making short–term adjustments to cope with the recession, they also need to take strategic decisions for the longer term. That is why airlines are still going ahead with some of the long–haul route launches and why American recently launched is long–haul fleet modernisation effort with the large (though conditional) order for 787–900s. US airlines have also continued to invest in the product (such as flat bed seats), which they hope will pay dividends in terms of revenues.

The airlines are in the fortunate position of having adequate liquidity, as well as promising prospects for building cash levels through the year. A recent Merrill Lynch report noted that compared to the last recession, industry balance sheets are relatively stronger with double the cash (about $20bn) and 30% less liabilities (on and off balance sheet). The US airline industry should get through 2009 without bankruptcies.