Southwest: Low-cost pioneer in transition

Jan/Feb 2008

Faced with cost pressures, low–cost pioneer Southwest Airlines has slowed ASM growth this year and is aggressively pursuing a "transformation plan" that focuses on the business traveller and aims to boost revenues by $1.5bn in the next two years. What revenue initiatives are in store, and to what extent will the business model change? How is Southwest positioned in respect of potential airline consolidation?

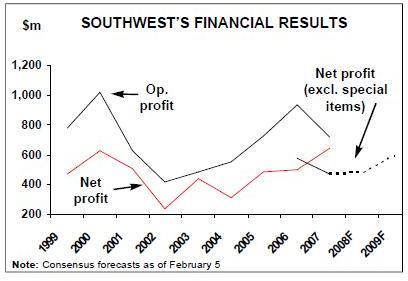

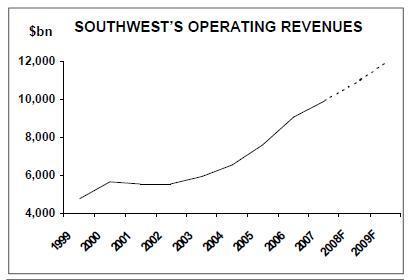

While Southwest continues to be among the most profitable US airlines — and its long term prospects remain bright — its earnings growth has ground to a halt over the past year. After stellar rises in 2005 and 2006, last year net profit before special items fell by 18.5% to $471m (on $9.86bn revenues). Fourth–quarter net profit before items was down by 13%, though per–share earnings were flat thanks to a reduced share count.

Currently, flattish earnings are expected in 2008. Southwest’s profits are falling mainly because its fuel hedges are wearing off. In the wake of September 11, Southwest was the only US airline with the cash (and the foresight) to take on extensive new fuel hedges at crude oil prices in the $20s and $30s (per barrel). Those hedges paid off handsomely when oil prices subsequently surged, saving the airline a staggering $2.5bn in 2000–2006. Now that the hedges are diminishing, Southwest has to pay more for fuel year–over–year even when there is no change in oil prices.

On the positive side, however, Southwest still has the best fuel hedges in the industry (by a wide margin). Also, the hedges will wear off gradually over several years, giving the airline time to adjust.

But Southwest also faces some structural issues, and those issues have worsened in recent years — additional reasons why the airline is now taking extensive action.

Because it is based on low costs, the Southwest model is very recession resistant, always coming into its own in hard times. By contrast, the legacy model comes on its own in boom times when the emphasis shifts to revenue generation. The legacies have more fare buckets to play with and international markets to turn to when the going gets tough domestically.

However, the legacy carriers’ deep cost cuts in recent years, in or out of Chapter 11, have narrowed Southwest’s cost advantage, particularly on the labour front. Southwest now has the highest- paid pilots for narrowbody aircraft in the industry. Although it continues to have excellent labour relations, it has been in contract negotiations with its pilots for 18 months. On the non labour front, Southwest may simply be running out of cost–cutting options.

The other major structural change, of course, is the surge in competition, both from the revitalised legacies and LCC copycats. In particular, there is progressively more direct competition from other LCCs. Virgin America took to the air in August; although it currently has a very small footprint relative to Southwest’s, it is a serious competitor worth watching. JetBlue has just announced plans to serve Los Angeles and various intra–West markets from May, which will bring it into direct confrontation with both Southwest and Virgin America.

In recent months Southwest has begun implementing an aggressive "transformation plan" that was first announced in June 2007. The plan includes elements that depart quite radically from the airline’s past strategies. First, to get the $1.5bn in incremental revenue needed to offset higher fuel costs and reach its financial targets, Southwest will focus heavily on the business traveller with product enhancements. Second, Southwest plans to go international from early 2009 with the help of multiple code–share partners.

Third, Southwest wants to aggressively take advantage of its 100m passenger base to sell travel–related services through its website. Fourth, Southwest is exhibiting uncharacteristic capacity discipline: it has dramatically slashed fleet and ASM growth plans this year in order to boost RASM.

In periods of turmoil in the US airline industry, Southwest has traditionally provided equity investors a safe option; after all, it has proved that it can prosper in any kind of environment. That still holds true, but the share price has fallen some 30% from its high in 2007 (after effectively going nowhere for several years) and yet the average recommendation on the stock is only "hold".

There seems to be considerable investor fatigue about Southwest. Some analysts have lost confidence in its prospects, no longer viewing it as a growth story. Others simply do not see any catalysts for a share price rally. Some in the financial community feel that Southwest took too long to reduce its planned ASM growth and that it is moving rather slowly with the transformation plan.

Some are not convinced that Southwest will get the $1.5bn extra revenues, because it has not provided the financial breakdown.

Of course, there are analysts, including at least Jim Parker of Raymond James and Michael Linenberg of Merrill Lynch, who are able to take a longer–term view. They recommend Southwest as a "buy" based on its proven ability to strengthen its competitive position in tough times. Those analysts are essentially focusing on 2009, when Southwest could return to strong earnings growth The shares could benefit this year if Southwest finds some good, low–risk growth opportunities resulting from legacy carrier consolidation.

Still highly profitable

To keep things in perspective, Southwest continues to be a highly profitable airline, with industry- leading margins. Its fourth–quarter operating margin (excluding special items) of 7.2% was the highest in the industry, exceeding Allegiant’s 6%, JetBlue’s 4.1% and AirTran’s 2.6%; all other carriers posted either losses or marginal operating profits for that extremely challenging period.

Last year was Southwest’s 67th consecutive quarterly profit and 35th consecutive year of profitability — both unprecedented in the airline industry.

Southwest’s full–year 2007 ex–item operating margin of 8.7% was the second–highest in the industry (after Allegiant’s 12.2%); most of the other carriers had operating margins in the 4.5% to 6% range.

This is going to be challenging year for Southwest because of severe cost headwinds; in addition to the diminishing fuel hedges, maintenance, engine overhaul and airport costs are set to rise. A loss in the current quarter is possible, though it is unlikely because revenue trends have been encouraging. The management is certainly hoping that the lower ASM growth rate, competitors' capacity cuts and recently launched product enhancements will boost RASM in 2008 to more than offset the cost hikes.

The current consensus estimate (as of February 5) is flat earnings in 2008, or up 5% on a per–share basis (from 61 to 64 cents). But the range of individual analysts' forecasts for that year is rather wide, from a 26% decline (45 cents) to a 30% increase (79 cents). Southwest’s management is confident the company will achieve its 15% EPS growth target in 2009 with the help of the planned $1.5bn revenue initiatives.

Post–2001, Southwest’s operating margins improved steadily from 7.6% in 2002 to 10.7% in 2006. Last year saw the margin dip to 8.7%. The current consensus estimates suggest a slight further dip to around 8% this year — something that could well be industry–leading performance.

At Raymond James' growth airline conference at the end of January, Southwest’s CEO Gary Kelly noted that "this has been the toughest decade in what is one of the toughest industries out there" and that "Southwest has always been a maverick", one that enjoys some "enduring strength". The airline’s special attributes that give it a competitive advantage include the following:

- Industry-leading fuel hedges In the fourth quarter of 2007, Southwest still had some 90% of its fuel requirements hedged at a crude–equivalent price of $51 per barrel — an excellent position in a period when market prices climbed to the $90-$100 range. The hedges saved the airline $300m in the fourth quarter and $727m in 2007. Without those gains, Southwest would not have made money in the fourth quarter.

The airline still has excellent fuel hedges in place for 2008: about 70% of its needs at $51. Currently, the hedges diminish to 55% at $51 in 2009, 25–30% at $63 in 2010 and 15% at $63–64 in 2011–2012. These positions give Southwest a significant competitive advantage, given that oil prices are likely to remain high (at least exceeding the high-$60s/$70 level) and because no other US carrier except Alaska has meaningful hedges in place beyond the current quarter.

Significantly, Southwest’s good near–term hedge position will give it time to build new revenue initiatives and, in general, adjust to a higher operating cost model.

The management’s goal is to go into a new year with at least 80% hedged, so that they can build a business plan around a known cost structure.

That goal is obviously not always achieved; for example, entering into new hedges at current prices does not make sense. However, Southwest has proved very adept in taking advantage of brief dips in crude oil prices, so it could add to its hedge positions if oil prices spike down this year due to recession.

- Lowest unit costs Southwest remains a low–cost producer, with industry–leading CASM and incredible efficiency levels. Despite labour and other cost pressures, the airline has held its non–fuel CASM at around 6.5 cents for the past seven years. This has been accomplished through continued productivity improvements; for example, headcount per aircraft declined from 86 in 2003 to 66 in 2007.

However, in recent years AirTran has effectively caught up with Southwest in the CASM league, as its unit costs have declined steadily in part because of an increasing mix of larger aircraft in its fleet (737s, versus 717s). On a non fuel, stage length–adjusted basis, by most estimates AirTran overtook Southwest in 2006 as the lowest–cost carrier in the US.

A unit cost analysis by R&S Airline Consultancy, summarised in a recent Raymond James report, found that Southwest still had the lowest total stage length–adjusted CASM in 3Q07: 7.1 cents at 1,000–mile stage length, compared to AirTran’s 7.4, Allegiant’s 8.2 and JetBlue’s 8.7 cents. However, when the impact of Southwest’s superior fuel hedging programme was eliminated, two airlines overtook Southwest in the CASM league. Allegiant and AirTran were now the lowest–cost carriers, with CASM of 6.7 and 6.8 cents, compared to Southwest’s 7.1 cents and JetBlue’s 8 cents.

- Strong balance sheet Southwest has one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry, with total assets of $16.8bn, shareholders' equity of $6.9bn and long term debt of $2.1bn at the end of 2007. The liquidity position is excellent, with cash and short–term investments of $2.8bn (28% of last year’s revenues) and an unused $600m revolving credit line. The lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio was 36% at year–end — some 20 points below the leverage seen in the mid–1990s.

The strong balance sheet has enabled Southwest to maintain investment–grade credit ratings (minimising borrowing costs and maximising flexibility), hedge for fuel, continue to pay dividends (now for some 126 consecutive quarters) and undertake aggressive share repurchasing. In the past two years, the airline has spent a staggering $1.8bn to repurchase stock, and a new $500m programme was launched in January. The shares are either retired or used to fund the company’s employee stock plan.

- Unbeatable culture, morale and brand Southwest’s operational integrity and service quality remain rock–solid. Its culture, staff morale, popularity and brand (low fares and great service) are as strong as ever. The airline has never laid off staff or cut pay. CEO Gary Kelly noted recently that those things are "never more important than at a time like this, when the industry and Southwest are going through change".

Southwest has a solid management team. The airline has staged a very smooth and successful leadership transition since 2001, with Gary Kelly taking over from Herb Kelleher.

- Large passenger base

Southwest has been the largest US airline in terms of domestic passengers uplifted for some years, but the management has only recently started mentioning that because the airline now wants to tap the 100m customer base to sell ancillary products through the web site.

Another positive is that, over the past decade, the route system has become more balanced and accessible as Southwest has expanded in the East, added transcontinental service and built significant operations at major hub airports such as Philadelphia and Denver (rather than focusing totally on secondary airports). While the western half of the country still accounts for about 70% of Southwest’s capacity (West 36%, Midwest 17%, Southwest 14% and Northwest 4%), East and Southeast now account for 14% and 15%, respectively.

Slower growth in 2008, acceleration in 2009?

Southwest has long had a strategy of growing at a brisk pace — 8% annual ASM growth has been the target in recent years — and resisting fare increases so as not to drive away traffic. The management always insisted that any retrenchment could embolden competitors. But in June 2007, after pressure from the investment community concerned about domestic demand weakness, Southwest reduced its planned ASM growth in 4Q07 and 2008 from 8% to 6%. Then in December, after fuel prices had surged and in anticipation of a slowing US economy, Southwest further reduced its 2008 ASM growth to 4–5%.

The ASM growth reduction is accompanied by a shift of capacity to more profitable markets. In the initial phase, implemented in October- November, Southwest eliminated 39 round trip flights, including long sectors such as Philadelphia–Los Angeles and Baltimore- Oakland, while adding 45 new flights in growth markets such as Denver and New Orleans.

This helped boost unit revenues in the fourth quarter. There will be another major schedule refinement in May, aimed at improving this year’s profits and giving the company time to focus on revenue initiatives. Southwest has not yet released the details but has said that there are no plans to drop any existing city pairs or new routes planned for 2008 and that there will be continued growth at Denver.

The 2008 ASM growth reduction has meant a surprisingly drastic scaling back of fleet growth. A year ago, Southwest expected to take 34 new 737–700 deliveries in 2008, followed by 39 aircraft in 2007. In June the 2008 net addition was revised to 19 aircraft. The latest figure is only seven.

Also surprisingly, Southwest has deferred only five aircraft with Boeing (to 2013). The plan is to take 29 new deliveries this year and retire 22 aircraft, resulting in a net addition of seven. Of the 22 retirements, 12 will be returned to lessors and ten will be sold during the first three quarters of this year.

Selling the 737s should not be a problem as global demand for narrowbody aircraft remains strong. Southwest expects to generate significant gains from the sales, which could reduce this year’s net aircraft capex by $200–300m. Excluding such gains, this year’s aircraft spending is expected to total $1.3bn, similar to last year’s.

While slowing overall ASM growth and focusing on more profitable markets, Southwest has clearly become more strategic with its growth efforts and is behaving even more aggressively than before at key locations. Denver is a prime example. After entering the market in January 2006 with 12–13 daily departures, Southwest built up the service at its typical pace to around 55 daily departures by 4Q07. One analyst suggested that Southwest had largely achieved critical mass in Denver. However, in January Southwest announced plans to boost the Denver daily departures to 79 with the May schedule.

In recent presentations Kelly has spoken enthusiastically about demand and revenue growth at Denver, calling the city a "remarkable expansion opportunity". Southwest spotted an opportunity in Denver because United has been downsizing there and the encumbent LCC, Frontier, has never really got its act together and continues to struggle financially. Southwest’s May growth spurt is potentially very bad news for Frontier; in JPMorgan analyst Jamie Baker’s analysis, it would result in Southwest being present in markets that account for over 40% of Frontier’s revenues.

There may be strategic thinking also behind the decision to return to San Francisco. Southwest recommenced service there in August — the same month as Virgin America began operations with San Francisco as its base. Southwest started out with a record number of flights for a new market and has had a "tremendous" response, achieving near–system average load factors there already in the fourth quarter. From March San Francisco will have 35 daily departures.

Raymond James' Jim Parker made the point in a late–January research note that even though Southwest is slowing its ASM growth to 4–5% this year, it is still likely to significantly increase its market position. This is because the legacy carriers, which account for 55% of industry revenue, will collectively reduce their capacity by something like 4% in 2008 (by current estimates). Furthermore (though this will not have much impact on market shares), the other major LCCs have also moderated their growth plans for 2008; for example, JetBlue will grow its ASMs by 6–9%, compared to 12% last year, and AirTran will grow by about 10%, roughly half of last year’s rate.

Parker also made the point that LCCs' aircraft deliveries are expected to pick up again in 2009 and 2010, "depending on economic conditions and potential consolidation of legacy carriers, which could cause LCC aircraft growth to accelerate".

Southwest’s management has repeatedly stressed that they continue to see "tremendous long–term growth opportunities", provided that RASM improves and costs are under control.

Currently, Southwest has 21 firm–order deliveries plus seven options scheduled for 2009. The 2010–2014 schedule includes 59 firm orders, 76 options and 54 purchase rights.

The management has also emphasised that, despite this year’s cutbacks, Southwest remains well–positioned to respond quickly to favourable market opportunities. Instead of selling or returning to lessors the 22 aircraft, the airline would like nothing more than to put some or all of them to profitable use.

Interestingly, in response to a question at Southwest’s fourth–quarter earnings conference call in January, Kelly disclosed that the airline is considering going into the aircraft leasing business. It would be a way to retain flexibility in the current economic environment and if the consolidation process gets under way.

Otherwise, there are no new developments on the fleet front. All of the new aircraft on order are 737–700s, which the management says is so well suited to Southwest’s strategy that they do not even anticipate any -800s in the mix. Having looked at smaller jets many times in the past 15- 20 years, Southwest says that at this point it is very much focused on just the 737. Southwest is working with Boeing and engine manufacturers on the next–generation 737, but Kelly noted that that type is unlikely to be in the market for at least five years.

New revenue initiatives

Southwest’s primary focus this year is to bring its revenues in line with its higher cost structure. The goal is to increase RASM by 10–15% in 2008–2009 (over the current level), which is roughly equal to $1.5bn of incremental revenue. This target is higher than the $1bn Southwest talked about in June because of the sharp hike in fuel prices in the autumn.

The $1.5bn target covers revenue from all sources — fare increases, schedule enhancement, ancillary revenues, etc. However, fare hikes and schedule changes can realistically bring only a fraction of the needed amount, so Southwest is focusing heavily on product initiatives aimed at the business travel segment and developing different types of ancillary revenues.

Incidentally, it may seem surprising that Southwest does not support industry fare increases, given its new revenue focus. Having the key player join in would make all the difference in getting domestic fare hikes to stick. But Southwest still sees it as a low–fare environment for leisure travel and is concerned about economic trends. As a short–haul carrier, it has to worry more about elasticity of demand than many of its competitors. Therefore, in revenue generation efforts as in other areas, Southwest marches to its own beat. The first batch of revenue initiatives, launched in early November, included a new "Business Select" product, enhancements to the FFP, a new boarding method and an "extreme gate makeover". The latter consisted of improvements to gate areas to include, among other things, lots of power points for customers' laptops.

Business Select, which costs $10-$30 more one–way and offers preferential boarding, a free cocktail and bonus frequent–flyer points, is a very modest (and low–cost) premium product even by LCC standards. But Southwest is unique and its business customers have evidently enthusiastically embraced the new offering. The airline expects Business Select to bring in $100m of extra revenues annually.

After years of analysis, Southwest decided not to adopt assigned seating to replace the open boarding system that was disliked by its business customers. Instead, the airline modified the process: it now issues passengers numbers dictating their boarding order, which effectively eliminates the need to stand in line to ensure a good seat.

These adjustments seem relatively minor, evolutionary rather than revolutionary. But Southwest has to tread carefully so as not to alienate its core leisure customer base. An important part of its appeal has always been its "low–fare, egalitarian reputation" (as the Wall Street Journal recently put it). But Southwest has also always been attractive to the business traveller, thanks to its excellent service quality and on–time performance, expansive network and frequent flights. In the words of CFO Laura Wright, "we have an airline that’s built for the business traveller".

Southwest has a great business model that its customers love. Wright said that extensive market research indicated that most of the customers did not want major changes to the product. The airline wants to "remain the low fare leader and, at the same time, improve our customer experience". When launching the product changes, Southwest reassured its leisure customers that it is merely transitioning from a "one–size–fits–all airline to the airline that fits your life".

That said, the product enhancements launched in the fourth quarter were just initial steps, with much more change coming this year and especially in 2009. This summer Southwest will begin testing satellite–delivered broadband internet access on several aircraft. It is in the process of implementing Galileo and Worldspan. Future initiatives will include further FFP enhancements, international code–shares, improved revenue management, major web site improvements and selling travel–related products and services through southwest.com.

Many of these initiatives reflect a realisation on Southwest’s part that it makes sense to take advantage of its unique position as the largest US carrier in terms of domestic passengers. The airline now recognises that it has huge opportunities to capitalise on southwest.com, which consistently ranks among the top travel sites in the world.

Southwest is relatively late in tapping ancillary revenue opportunities, and it has also been criticised for moving rather slowly since announcing the plans. Why did it not do this earlier, and why now the snail’s pace?

First, there was simply no pressing reason to do this earlier, whereas now the imperative is there due to the surge in energy prices. Second, Southwest was built very differently from other airlines and, as a result, it has had some serious "catching up" to do on the technological front.

As the management explained recently, Southwest was built to do one thing and do it well: carry passengers from A to B domestically. There was a lot of beauty in simplicity (such as the lowest costs in the industry), but as the times changed, Southwest did not have the flexibility in its systems to exploit other opportunities. Its reservation system was built for its unique needs as a domestic carrier; developing international capability (to handle foreign currency, taxes, interlining, etc.) now is taking 24 months. Likewise, the web site was designed solely to sell Southwest flights.

Consequently, much of this year’s effort focuses on getting the technology in place to support the planned activities. Southwest will be replacing its point of sale system at the airport (including boarding and baggage systems), its back–office ticketing system and revenue accounting system. New software will provide international code–share capability with multiple partners. Construction work is also under way to enhance Southwest’s cargo capabilities.

While Southwest is excited about the potential for hotel, car hire and other travel–related ancillary revenues, those activities are not a top priority and probably will not come about before 2009. This is partly because significant improvements to the web site are needed to generate the kinds of ancillary revenues that Southwest wants, but also because the airline wants to make sure that it gets the 4Q07 product initiatives right.

One reason there has not been more enthusiasm in the investment community about the $1.5bn incremental revenue goal is that Southwest has not provided the breakdown, except for the estimate that Business Select will contribute $100m. Kelly said recently that the airline does not really know but that it has "ideas of the ranges of potential" for each component and that the aggregate opportunities are "well in excess of $1.5bn". Kelly also made the point that much of it will be very high–margin business.

Southwest’s management have said that they see "hundreds of millions of dollars" revenue potential from expanded code–sharing. The code–shares with ATA, which began in 2005 and include ATA–operated flights to Mexico and Hawaii, have been highly successful, generating $50m to Southwest in year one at minimal marketing cost.

The plan is to initially expand code–sharing with ATA in near–international markets — Mexico, Caribbean and Canada — from early 2009. Later Southwest will look for additional partners to fly to Europe and Asia, using the partners' widebody aircraft.

Southwest will be attractive as a potential partner for many European carriers, thanks to its vast domestic network, 100m passenger base and great brand. Such deals should also be extremely beneficial to Southwest, enabling it to boost its load factors (which never exceed the low–70s) and offer overseas destinations to its own customers.

However, the potential transatlantic partners would probably have to operate to Baltimore or Philadelphia, and it may not be easy to get workable connections because Southwest is very much a point–to–point carrier. Kelly recently explained it as follows: "We don’t want to begin banking, because that would impair our productivity.

We don’t schedule for connections at all today. That is one of the things we need to be mindful of as we look for code–share partners. We're going to have to fit those relationships in a way that we don’t radically change our scheduling practices." Southwest is not contemplating own–account international operations any time soon — even West Coast–Hawaii flights are currently not possible because its 737–700s are not ETOPs. But Kelly noted recently that once the ticketing systems are built to handle the code–shares, Southwest would be able to offer the (near–international) product itself, should it decide to do that. "It is clearly something we have out there as a possibility."

Raymond James' Jim Parker has argued for quite some time that Southwest has enormous potential to generate incremental revenue and earnings because of its broad reach of over 100m passengers and the high degree of trust in the Southwest brand. Southwest is mainly talking about selling "very straightforward travel–related products" — hotels, rental cars, vacation packages and suchlike. But it is also taking some steps towards unbundling the airline product, as indicated by its recent decision to start charging customers $25 for their third checked bag (which was previously free).

Well-positioned for consolidation

Southwest’s balance sheet and other special attributes make it well positioned to benefit from whatever legacy airline consolidation or capacity reduction may take place this year.

A more rational capacity and pricing environment would make it easier for Southwest to reach its RASM targets. Capacity cuts by the legacies in specific markets or secondary hub closures would create potential new market opportunities for LCCs. Large merger transactions could create opportunities for LCCs to acquire assets such as gates and slots at capacity constrained airports. And there could even be an opportunity for a financially strong LCC like Southwest to acquire another airline.

There is always speculation about what Southwest might or might not do. It is often argued, for example, that Southwest would not be interested in acquiring another airline that does not have 737s. But the message coming from Southwest’s management is that anything is possible.

At the end of January, Kelly explained Southwest’s intentions as follows: "I can see our participation ranging from doing nothing and benefiting from reduced capacity by our competitors, which is what happened with the US Airways/America West transaction (they shrunk by 15% and we gained market share), all the way to us potentially combining with another carrier." Kelly also indicated that a different fleet would not necessarily be a "deal–killer" in an acquisition, because there are ways to deal with that.

Southwest has not been very acquisitive historically, but it has completed some very successful transactions, including a merger with Morris Air in 1993 and the ATA rescue deal in late 2004. It has also gained great growth opportunities through legacy hub closures (San Jose, Raleigh/Durham). Southwest will be actively evaluating opportunities that may arise this year and will be prepared to move quickly.