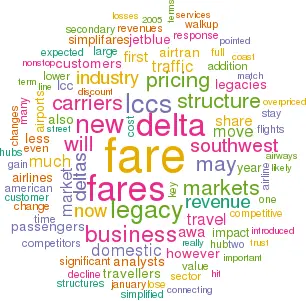

SimpliFares: a survival strategy for the US legacy carriers?

Jan/Feb 2005

Delta’s new domestic fare structure, called SimpliFares, has been hailed as a "pricing revolution" and "nothing short of a historic change in US travel" (The Wall Street Journal).

Pundits have predicted that, after a severe revenue hit this year, the surviving legacy carriers will gain in the long run through traffic stimulation and recapture of market share from LCCs. But will the legacies have the cost structures to pull it off? Could they really outwit Southwest and JetBlue?

The SimpliFares programme is regarded as the most important pricing development in the US legacy carrier sector since American’s value pricing in 1992. Under Bob Crandall’s leadership, American tried to change industry pricing by introducing a simplified and reduced domestic fare structure. But the move triggered a fare war, causing heavy losses for all airlines, and the change had to be abandoned. That was before the LCC era. Southwest, the only sizeable LCC, was largely unaffected by the move.

The post–September 11 environment has seen many limited attempts to introduce LCC–style fare structures. They have fallen broadly into two categories: fare reforms by niche–type carriers looking to increase market share, or experiments by the larger majors, aimed at keeping LCCs at bay at specific hubs.

In the best example of the niche–type value pricing, America West (AWA) reformed its fare structure in March 2002 in response to business travellers' demands. The airline introduced a simple, flexible pricing structure, with fares 40–70% lower than competitors' walk–up fares.

The other major carriers matched the fares only selectively, which meant that the move paid off for AWA in terms of market share gain and revenue generation.

AWA avoided a hostile response from competitors because of its small size and geographically limited network. The pricing formula worked well because, as a leisure–oriented carrier, it did not have significant business segment revenues to lose in the first place. Moreover, it had a low cost structure.

US Airways came up with "GoFares" — a low fare structure very similar to SimpliFares (with fare caps at $499 and no Saturday night stay requirement) — in response to Southwest’s entry to its Philadelphia hub in May 2004. There were predictions that the move could lead to industry–wide fare reform, but US Airways has not been able to implement it fully because of its high cost levels and poor reserves — it is in Chapter 11 and fighting to stay in business. Nevertheless, GoFares have been expanded and are now used by 25% of US Airways' domestic passengers, adding to the competitive frenzy on the East Coast.

The latest hub fare experiments have included Delta’s SimpliFares project in Cincinnati (the precursor to the nationwide programme) and a similar project by American in Miami. Delta launched its experiment in August as part of its "transformation plan". American began testing a simplified lower fare structure at its large Miami hub in November, with the aim of luring back passengers who had begun driving to secondary airports served by LCCs.

The common theme with the large legacy airlines' value pricing experiments in the past was that they were revenue–negative. Traffic and load factors increased, but that was more than offset by a decline in yields. Because of the adverse impact on the bottom line, no airline could justify implementing the changes.

Delta’s SimpliFares represent the first attempt by a large legacy carrier to "switch sides" to the LCC camp in terms of revenue strategy. Unlike AWA in 2002, Delta expects competitors to match the fares — and it does not expect any market share gain from the other legacy carriers.

Why now?

Fare cuts were the last thing that the US airline industry needed at a time when domestic unit revenues are extremely depressed and the industry is headed for its fifth year of steep losses. So why did Delta choose to do it now?

The move obviously reflected both industry changes and company–specific factors. As regards to the latter, Delta was encouraged by the results of the Cincinnati experiment — a 30% traffic boost and, evidently, not–too–disastrous financial losses.

The timing also reflected the fact that Delta is now in a stronger position to withstand a near term revenue hit, after narrowly avoiding Chapter 11 in October and obtaining $1.1bn in additional funds under new credit facilities in December. Nevertheless, analysts remain concerned about its cash position — one remarked that Delta "does not have much room for error".

On the industry side, the key development is that, after a decade of growth, LCCs have gained critical mass, have become a credible alternative to business travellers and now control pricing in the domestic market. The legacy carriers, in turn, rely much less on high–yield traffic and continue to lose market share. As Delta’s CEO Gerry Grinstein put it, "the industry has reached a tipping point".

Once–risky pricing moves are now much less risky or even deemed necessary. S&P’s Philip Baggaley noted recently that "ultimately for Delta, the risks of adopting a simpler, lower fare structure have decreased, while the risks of not taking action have increased." In other words, the short–term revenue loss, while material, is much less than it would have been in the late 1990s and the legacies "now stand to lose more by keeping the old fare structures".

Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl expressed well the sentiment among analysts that the move was necessary: "Delta has imposed a badly needed change on the industry in the way it prices its product”. Delta cited customer feedback calling for "simpler, more affordable everyday fares" as a key reason. It wanted to fulfil the request to improve the travel experience and "win back customer trust".

That may sound like a meaningless slogan, but "trust" is an important concept in the US, helping to explain why many business travellers have switched to LCCs and why Southwest and JetBlue can even charge slightly higher fares than competitors. Traditionally, the legacies have used complicated fare structures to squeeze revenues from business passengers. The differentials between full and discount fares grew so large that business travellers began voting with their feet in early 2001. That caused a domestic revenue slump even before September 11 and the subsequent economic downturn, which led to a further tightening of corporate travel cost control policies. The bottom line is that customers do not trust the legacies to give them good value for money.

How significant a change?

Delta’s new fares, introduced in the contiguous 48 states from January 5, slashed walk–up fares by up to 50% and capped fares at $499 (one–way) in economy and $599 in first class. The largest fare reductions were in key business travel markets such as New York–Dallas, which previously had walk–up fares in the $1,000 range.

However, Delta’s fare reductions were much smaller in markets where it already competed with LCCs — a significant 70% of its domestic routes. Also, the new fares remain higher than those offered by LCCs — both AirTran and Southwest issued statements saying that they would have to raise their fares to match Delta’s.

As the Wall Street Journal noted, it was "a subtle but clear admission that most domestic first class isn’t worth much more than $100". By comparison, AirTran charges $35-$75, depending on the length of the flight, to move passengers to the front cabin.

Delta’s new fare structure is much simpler than the old one. There are now only six fare categories for economy and two for first class. Passengers can choose between refundable or non–refundable tickets and obtain further savings by booking three, seven or 14 days in advance.

Significantly, Delta has totally abolished the unpopular Saturday night stay requirement.

However, a round trip purchase and one–night stay are still required on all other than walk–up fares. And the new fares are available only on delta.com or from travel agents — Delta has imposed $5 and $10 fees for telephone and ticket office bookings.

Therefore the fare structure is not as simple as the offerings of LCCs.

Criticising the Delta fares for what it called "a litany of convoluted rules", AirTran pointed out that it does not "nickel and dime customers with junk fees based on how a customer makes a reservation". It remains to be seen if that matters to travellers.

Delta is only following legacy sector practice with the new booking fees — part of a trend of "unbundling" airline service, namely separating food, reservations and suchlike from the ticket price.

Fare analyses will continue to show a large number of Delta fares available in a given market,because the new pricing structure does not apply to Delta–marketed code–share flights or pro–rated flights that connect to international services. In addition, there are "sale fares" in response to competitors' fare sales — so much for simplification.

In addition to the fare reform, Delta has simplified its FFP and is redesigning its aircraft interiors (brighter, with leather seats). Later this year it will unveil improvements to delta.com, a new food product and new employee uniforms. At the end of January, it began de–hubbing Dallas Fort Worth in favour of boosting service at its three main hubs.

Interestingly, despite the obvious attempt to move domestic mainline operations in the direction of Song, Delta is expanding, rather than merging with, its low–fare unit. Song will grow by one third in May, with the addition of 12 757s and new transcontinental and Caribbean services. Rather than causing confusion, Song has gained a strong identity separate from Delta’s and is highly regarded by passengers. Delta regards it as "a successful test bed for new and innovative ideas".

The other legacy carriers were expected to fully match the fare structure in markets where they compete with Delta. Although it is too early to reach a final verdict, by late January two things had happened. First, the airlines had not matched the fare structure entirely in competitive markets — they typically left out hub markets and did not introduced fare caps. Second, American had broadly matched Delta’s fare structure nationwide, including hubs, with modifications such as fare caps at slightly higher levels.

However, now that American has embraced the concept, it may only be a matter of time before everyone joins in. The latest reports from travel analysts indicate that business fares have declined sharply all around the country. A survey by Harrell Associates, quoted in the Wall Street Journal, found that business fares in the top 40 markets were down by one–third from a year ago.

Short-term pain, long-term gain?

Even though seats sold at full fares account for only a few percent of legacy carriers' total domestic seats these days, those tickets still account for a fair chunk of revenues. Consequently, the industry is bracing for a significant negative revenue impact in the next 6–12 months. Merrill Lynch’s Michael Linenberg has estimated the potential 2005 industry revenue dilution at $2–3bn, or a 3- 4% decline from 2004’s $70bn.

The impact is likely to be felt throughout the legacy sector, depending on competitive overlap and the extent of LCC competition already present. Some analysts believe that Northwest could take the largest unit revenue hit this year because it has historically been less exposed to LCCs in its core markets.

Of course, the Delta–imposed fare changes are only one of a string of serious problems that the industry faces in 2005. In addition to the dismal revenue environment, the challenges include a severe capacity glut (particularly on the East Coast) and continued high fuel prices.

However, the good news for the airlines that make it through 2005 is that the negative effects of the fare changes are expected to diminish and revert to positive over time. The legacy carriers are counting on the following:

- Traffic stimulation The simplified lower fares are expected to stimulate price–sensitive business travel demand, leading to more trips. Business travel is more inelastic than leisure travel, but perhaps because the fares were previously exorbitantly high, Delta has reported an enormous passenger response to the initiative.

- Market share improvement Some price–sensitive travellers are expected to shift from connecting flights (typically operated by AWA and LCCs) to nonstop flights. Others will shift from secondary, less convenient airports (served by some LCCs) to primary airports. Some customers will return because of the FFPs and larger networks offered by the legacy airlines.

- Better traffic mix There is potential to offset some of the yield decline resulting from the fare reductions through an increase in the business and full fare content of traffic. In addition to existing business passengers making more trips and new business customers pulled from LCCs, some existing discount fare travellers may upgrade to full fare to get the flexibility, now that the fare differential is relatively small.

- Productivity and efficiency benefits The shift to web bookings will produce significant cost savings — Delta’s aim is to move half of its customer transactions to its web site (currently20%). Also, the new lower fares will reduce or even eliminate the need for group or corporate discount programmes, which are time–consuming and expensive to negotiate and administer.

Delta apparently has 6,000 such programmes. However, the downside is that all of those corporate customers will be free to switch to LCCs if they so choose.

Implications for LCCs

In the short term, LCCs generally are not likely to experience revenue dilution as a result of the Delta–led fare cuts. They have not had to reduce their own fares and are unlikely to lose customers in the near term. As Southwest’s CEO Gary Kelly noted in the company’s fourth–quarter conference call, "so far it looks like a non–event".

The market share shifts that Delta and the other legacies are counting on would only affect the LCC sector in the longer run and in a gradual fashion. However, the consensus among analysts is that only certain types of LCCs are in danger of being severely affected.

The worst–positioned LCCs are those that depend heavily on connecting traffic that has been attracted by undercutting legacy carriers' nonstop fares — particularly AWA and ATA, but also AirTran.

According to JP Morgan, AWA, ATA and AirTran generate 24%, 23% and 18% (respectively) of their revenues in connecting markets where nonstop alternatives are available. For Southwest and JetBlue, those percentages are only 4% and 3%.

UBS analyst Robert Ashcroft aptly described the at–risk airlines as "hybrid LCCs/secondary network carriers". He also pointed out the irony that AWA’s early embrace of value pricing was instrumental in its turnaround three years ago, and now "it may be in danger of having those clothes stolen by bigger, more comprehensive primary networks."

While AWA has only reported minimal impact so far, in late January it decided to withdraw from most transcontinental markets by the summer, in favour of developing more international services.

While AirTran is more of a true LCC, it is vulnerable also because of its extensive route overlap with Delta, as both have their main hubs at Atlanta, and a heavy East Coast presence.

Analysts are concerned about its plans to grow ASMs by as much as 25% this year (19 aircraft deliveries). AirTran may have to come up with some new strategies, but it is worth bearing in mind that it has survived a constant barrage of extremely aggressive competitive moves from Delta over many years, with little adverse impact on its bottom line.

The consensus opinion is that Southwest and JetBlue will not feel much impact from the Delta–led pricing moves. They are really in a category of their own, in terms of financial strength, culture and efficiency. They have strong brands and enjoy a loyal following of customers. JetBlue also has a product that many view as superior to the legacies' offerings.

Another strength enjoyed by Southwest and JetBlue that may prove particularly important is that they dominate their key markets, just like the legacy carriers do. An analysis by UBS shows that Southwest accounts for over 70% of the total traffic in its top 100 markets, while JetBlue has a 55% share in its top 50 markets. Legacy carriers' shares are in the 45–63% range, but AWA’s and AirTran’s are only about 20%.

But the new pricing developments may force Southwest, in particular, to re–examine some of its strategies. First, relying on secondary airports may make less sense if fares decline at primary airports (though Southwest has pointed out that secondary airports do have some advantages — for example, they are easier to get to and have less congestion). Second, the traditional strategy of going for "overpriced and under–served" markets is at risk, because the legacies' fare cuts may have eliminated many overpriced markets.

Kelly indicated that Southwest did not really see any new threats here — that it was already mindful of the fact that, as time goes by, it will face more and more low–fare competition. In other words, it would have to adjust its strategies over time anyway.

Because of the reduction in overpriced market opportunity, some analysts are predicting that LCCs will see reduced profit margins and slower growth, potentially meaning aircraft order deferrals or cancellations. However, while such scenarios may materialise for the weakest companies, there are two further reasons why the LCC sector overall may not suffer. First, the legacy carriers may be too financially distressed to offer effective competition. Second, the strongest LCCs, led by Southwest, are likely to be the main beneficiaries of industry restructuring.