Alitalia: is KLM/Air France a solution?

February 2004

2004 is a crucial year for Alitalia. Italy’s national airline is likely to report a massive operating loss, over €400m, in 2003 — its fifth straight year without an operating profit.

With further state aid no longer a possibility, can Alitalia survive much longer, or will a new cost–cutting plan be enough to persuade KLM and Air France to accept it into their merged operation, thus ensuring the future of an airline that launched operations back in 1947?

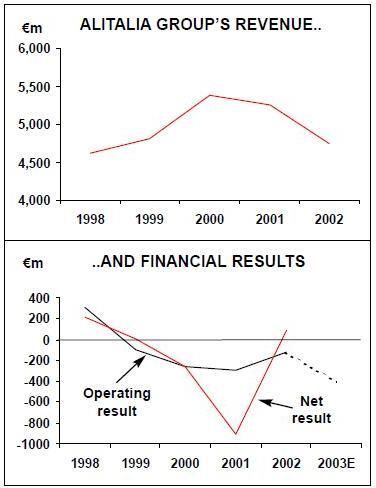

Struggling throughout the 1990s, Alitalia’s survival was based on receiving €1.4bn in "one time, last time" state aid in 1997. But by 2001 the Alitalia Group’s financial performance had deteriorated to a net loss of €907m in 2001. In 2002, Alitalia cut its operating loss by almost two–thirds and posted a net profit for the first time since 1999 (see chart opposite). However, this net figure was boosted by the sale of non–core assets and €172m compensation paid to Alitalia by KLM for the termination of a previous partnership.

Also in 2002, Alitalia benefited from a controversial recapitalisation in the form of a €1.4bn rights issue — nearly €900m came from the Italian state via the Ministry of Finance, which still owns about 62% of the airline, while the rest was underwritten by a consortium of international commercial interests, including Merrill Lynch and CSFB.

With the effects of the Gulf War and SARS hitting traffic in the first half of 2003, last year was very painful for the airline. Alitalia is exposed to the Middle East market, and traffic on many routes fell substantially after the Gulf War (Malpensa–Beirut traffic fell by 72% and Malpensa–Dubai traffic by 67%).

In the third quarter of 2003 Alitalia posted an operating loss of €22m — compared with a €58m operating profit in July–September 2002 — and a loss before extraordinary items and taxes of €48m, compared with a €26m loss in 3Q 2002. On top of the poor first–half of the year, this meant that Alitalia’s cumulative operating loss for January–September 2003 came to €284m and cumulative loss before extraordinary items and taxes totalled €365m — compared with an operating loss of €5m and loss before extraordinary items and taxes of €93m in 1Q–3Q 2002.

Overall, while total ASKs rose by 3.3% in January–September 2003, RPKs fell by 3.7%, with revenue per ASK falling by 10.9% and yield dropping by 11.2% over the period.

Domestic routes suffered a 4.4% drop in revenue per ASK and a 9% fall in yield. But international routes fared even worse, with a 12.1% drop in RASK in January–September 2003 and a 9.2% fall in yield.

In a presentation made to analysts in December 2003, Alitalia estimated that RASK would be around 9% lower in 2003 than 2002, while ongoing cost–cutting would reduce cost per ASK by just 4% — leading to a substantial worsening of the airline’s operating result.

When the full–year results are released in the next couple of months, they are expected to show an operating loss of at least €400m.

Underlying problems

So what is the reason for Alitalia’s continuing poor performance? Poor, politically appointed management, a reliance on state aid and all–powerful unions are the obvious factors. Yet, according to Alitalia a major problem is Italy’s geographical position; as it states in is 3Q 2003 report, "[Alitalia] operates in a country that lies in a peripheral position with regards to the main flows of international and intercontinental traffic … and a social/economic structure offering much lower levels of high yield traffic than its competitors".

In fact, Italy is the fourth richest EU country with a domestic market of over 15m passengers and an international market of 40m. What’s fundamentally happening is that a largely unreconstructed flag–carrier is increasingly meeting low–cost competition. This is reflected in rapidly eroding yields and market shares.

According to Alitalia, in the third quarter of 2003 "yield erosion increased to a critical level…caused by even tougher competition in terms of ticket prices, essentially as a result of overcapacity on the market and the increasing penetration by LCCs".

Ryanair currently operates to 14 destinations in Italy and offers flights throughout Europe from its new hubs at Rome Ciampino (launched in January 2004 and the base for four Ryanair aircraft) and at Milan Bergamo. easyJet operates to five Italian destinations from the UK, but also serves Milan Linate–Paris Orly and Naples- Berlin. Closer to home, volareweb — the LCC subsidiary of Alitalia’s ex–partner Volare and based at Milan Malpensa — launched operations in March 2003 with eight A320s serving 26 destinations through Europe.

To put the yield erosion in perspective: of the €139m reduction in revenue in 1Q–3Q 2003 compared with the previous year, according to Alitalia €68m was due to falling yields (though this was partly offset by increased traffic) and €48m to the strengthening of the Euro against the Dollar and Yen.

More cost cutting

For Alitalia — as with most other European flag–carriers — the only realistic action it can take in the face of falling yields is to cut costs yet again. Measures initiated after September 11, 2001 included the sale of non–core assets (disposals brought in €300m in 2002 and 2003), renewal of the long–haul fleet and the introduction of an early–retirement programme.

A total of 55 cost–cutting measures were implemented in 2002, including a trimming of 900 staff through early retirement and another 900 reduction through disposals.

But this isn’t enough, and in July 2003 Alitalia hired a US consultancy called TurnWorks — founded by Gregg Brenneman, ex–COO of Continental Airlines — to advise it on strategic matters.

In the third quarter of 2003 the Group undertook a widespread analysis of its strategy and organisation that led to a new business plan for 2004–2006, formally adopted by the board in October 2003.

Soberly entitled the 2004/06 "Industrial Plan", its measures include:

- Job cuts of 1,500, with another 1,200 positions likely to go through outsourcing

- Suspension of the annual salary rise (due in January 2004)

- Investment of €1.2bn on fleet renewal through the three–year period.

- Other cost–cutting measures, in all areas of the Group

- A planned rise in ASKs of 9% per year, via increased frequencies on major routes and new destinations in key markets

- Further overhaul of the Alitalia fleet

- New commercial policies, including more direct sales and strengthening of FFPs

- Efforts to improve Alitalia’s poor reputation for reliability, specifically in terms of below average on time performance and poor baggage handling.

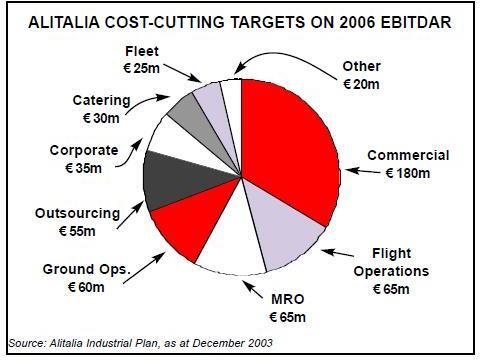

Altogether, cost cutting in the Industrial Plan is designed to save €535m a year by 2006 (see chart, page 10, for a breakdown).

Alitalia claims these measures will cut operating losses to almost zero in 2004 and push the group into an operating profit in 2005.The main problem with this plan is Alitalia’s unions, which are fiercely protective of its members and fearful that these announced job cuts are just the start of a deep cull of the workforce. But in both pilot and flight attendant areas, Alitalia claims it faces low utilisation levels, absenteeism and high costs from crews based at Milan Malpensa. Flight personal contracts need to be renegotiated, Alitalia states, allowing the company to "grow for free".

At the end of 3Q 2003 the group workforce stood at 20,934 — just 408 less than a year earlier and only 1,500 less than in 2001.

These reductions came from early retirements and the disposal of assets such as Italiatour and Eurofly. Under the new plan, Alitalia aims to reduce group staff to 18,000 by 2006, via 1,500 redundancies, 300 retirements and 1,200 outsourced jobs. This is a staff reduction of less than 18% in five years, which is not a huge stretch in relative terms but a massive reduction given the power of the unions and management’s previous reluctance to discuss plans with its workforce.

Unsurprisingly, relations between management and the unions are strained. Even before the new Industrial Plan, in May 2003 a dispute arose with cabin staff over plans to cut flight attendants from four to three on domestic routes using MD80s. After unofficial action and prompted by the government, Alitalia sat down with five unions representing cabin staff in June, and by early July an agreement was reached whereby Alitalia withdrew its plans in return for changes in working practices that saved an equivalent amount of cost.

At the same time as the new Industrial Plan was unveiled, Alitalia’s management said that it wanted to "involve the entire workforce in all the company major projects" — but this statement was considered as hypocritical by unions given that the new plan had barely been discussed with the workforce.

Unions therefore held stoppages and walkouts in November and December as an immediate response to the business plan.

The company reacted by pointing out the consequences of not carrying out major cost cutting. In a letter send to Alitalia staff at the end of 2003, CEO Francesco Mengozzi wrote: "If this were the case, we can calculate that within the space of 18 months, based on simple projections of current performance, we would have used up all our financial resources, plunging ourselves once more into a major financial crisis."

But the unions stood firm and Silvio Berlusconi, the right–wing Italian prime minister, stepped in to force management to hold negotiations with the unions. Berlosconi’s decision to intervene is likely to be related to the intense pressure the Italian PM has come under in 2003 from Italy’s unions after his government tried to implement a series of controversial measures. In October there was a massive general strike against Berlosconi’s plans to substantially reduce pension provisions for workers across the country (and which, incidentally, forced Alitalia to cancel hundreds of flights), and in December protests brought more than 1m people into the streets.

Whatever the motivation, Berlosconi’s pressure was successful, and at the end of December management agreed a temporary compromise with unions over the implementation of the Industrial Plan.

Labour measures in the plan are now temporarily delayed via a moratorium until January 31st, and a planned pay rise in January (that had been cancelled in the Industrial Plan) went ahead pending alternative ways of cutting equivalent costs that unions and management hoped to agree on during negotiations through January.

But these negotiations have not gone well, and on January 19th unions representing flight attendants and ground staff went on strike in an action that forced the cancellation of half of all Alitalia’s flights that day. Further talks are scheduled for early February, ahead of planned industrial action (which this time will include the pilots' union). Worryingly, unconfirmed reports in an Italian newspapers suggest that the delay in cutting labour costs will cost Alitalia up to €60m, meaning that the airline will fail by a long way to cut its operating loss to almost zero in 2004, as was the target in the Industrial Plan.

Elsewhere, of the €230m commercial cost savings Alitalia plans to make on an annual basis by 2006 (which reduces to €180m at the operating level after €50m of "implementation costs"), €110m will come from extra direct sales, €80m from reducing commission in the domestic market and €40m from reducing commission in the international market (Alitalia had already cut travel agent commission on domestic flights from 6% to 3% in May 2003). In terms of direct selling, Alitalia plans to increase the proportion of web sales from zero in 2003 to 14% by 2006, and call centre bookings from 2% in 2003 to 9% in 2006.

Alongside the Industrial Plan there was a reorganisation of management, including the hiring of the grandly–titled Chief Production Officer — who will be in charge of operational efficiency — and a Core Business Co–ordinator.

Group structure has also been improved, completing reorganisation that began in 2002.

Leisure and diversified businesses have already been disposed of, leaving the group to concentrate on its core air passenger business. Three areas — logistics & cargo, ground handling and engineering & maintenance — have been singled out for possible joint ventures/ partnerships (within engineering & maintenance, an engine shop joint venture with Lufthansa Technik has already been agreed, while on cargo Alitalia is in negotiations with Air France). Five other areas — administration, revenue accounting, information technology, call centres and other support activities — have been earmarked for possible outsourcing.

As part of its ongoing efforts to divest non–core assets (it sold tour operator subsidiary Italiatour and IT company Sigma in 2002/03), Alitalia sold an 80% stake in charter airline Eurofly to the management and Milan banking interests (via a financial company, Effe Luxembourg) for €10.8m in August 2003.

Eurofly is based in Milan and operates six A320s and two A330s to destinations in Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Fleet changes

Alitalia currently operates a fleet of 184 aircraft (see table, page 12), but by 2006 it plans to have a fleet of 12 777s, 16 767s, 46 Airbuses, 69 MD80s and 36 regional aircraft, making a total of 179 aircraft. The reduction in the fleet means that the ambitious ASK growth target over the next three years will come from greater utilisation as well as changes in configuration. 767 capacity is increasing from 205 to 223 seats, MD–80s from 131 to 141 seats and MD–82s from 150 to 164 seats.

In May 2003 Alitalia received the last of six 777–200s it ordered from Boeing at a cost of $540m and financed by Barclays and the US Export–Import Bank. These were a direct replacement for Alitalia’s fleet of 747–200s, which have all now been disposed of. Alitalia also contracted to lease four further 777–200s from GECAS, the last of which will arrive in 2Q 2004.

Alitalia is also renewing its regional fleet with Embraer and ATR aircraft, flown by subsidiary Alitalia Express. Based in Rome, Alitalia Express was launched in 1997 from the remaining assets of Avianova. It operates 26 aircraft to scheduled and charter destinations throughout Europe and in 2002 carried 1.2m passengers.

The one remaining question is over what will replace the 89–strong MD–80 fleet. A decision has now apparently been put off until 2006, and 20 retirements will be made over the next three years, their capacity being replaced by extra seats on remaining aircraft as well as better utilisation. On cargo, Alitalia is phasing out its 747Fs, though in the interim two will remain on wet lease though 2004. Alitalia is selling two of its 747–200Fs to Russian cargo airline Volga Dnepr and converting its three MD–11s into freighters.

These fleet changes go hand in hand with a new operational strategy that sees Alitalia trying to shore up its domestic position against growing competition through the defence of its dominant position at Rome Fiumicino and Milan Malpensa airports. In short–haul, the regional jet and turboprop fleets will feed these hubs, although jets may serve secondary markets as well. As well as Alitalia Express, the Alitalia Group appears keen to defend its domestic position via a strategic link–up with one of its competitors.

In July 2003 AGCM — the Italian competition body — blocked code–sharing between Alitalia and existing Italian partner Volare on nine domestic routes (though code–sharing on five other domestic and eight international routes was allowed).

This decision was partly responsible for Alitalia ended the Volare partnership in September 2003, although anyway Alitalia had been in talks with Meridiana since March 2003 on a code–sharing deal and perhaps the purchase of a majority stake. Based in Sardinia, Meridiana operates 21 MD–80s and BAe 146s to 16 scheduled destinations throughout Italy and Europe. While not a traditional LCC, in early 2003 it adopted a "low fares" policy (with fares of €9-€49 on 1.5m seats), which boosted load factor by 9% and traffic by around one–third. Talks between Alitalia and Meridiana have not yet reached a conclusion, which may be due to worries about scrutiny from AGCM. Alitalia has approximately 50% of the Italian domestic market and Meridiana more than 15%.

Outside the domestic market, Alitalia believes it has better prospects, particularly on major O&D routes to Europe served from Malpensa and Fiumicino. On medium–haul, A320–types will serve peak frequencies, the 70–seaters will serve off–peak frequencies while the MD80s will operative to "price–sensitive and leisure markets".

On long–haul routes, Alitalia’s plans include greater frequency on many services in 2004 as well as the planned launch of new routes to Washington, New York, Boston, Toronto and Delhi. The airline will be helped by long–haul commonality (to just 767 and 777 models), which will be completed this year when the MD–11Cs are converted into freighters, while long–haul aircraft utilisation is planned to rise to 14 hours to 15 hours a day in 2004. But despite these moves, whether Alitalia can seriously build up profitable longhaul routes without assistance from Air France and KLM remains to be seen.

Is this enough?

Alitalia’s Industrial Plan is ambitious.

Management says its prime target is an EBITDAR as a percentage of revenues of 15–17% by 2006 — which is a long way off the 1.1% EBITDAR margin it achieved in the first nine month of 2003.

Can Alitalia really achieve this? Even if it comes to some arrangement with unions and hits the cost–cutting targets, it may find that the goalposts have moved even further through continuing yield erosion — the real threat to the future of Alitalia.

In the short–term, analysts will examine the full–year 2003 accounts to see what it is happening to Alitalia’s debt position. As at 30 September 2003, the Group’s net financial indebtedness (long–term plus short–term debt minus cash) had increased to €1.2bn, compared with €900m as 31 December 2002, largely due to the financing of six 777s. This isn’t huge, but the trend is in the wrong direction, and €180m of long–term debt has to be repaid this year and €250m in 2005.

Yet cost–cutting by Alitalia’s management is not just being carried out for its own sake — it is also a means to an end, and that end is entry into the proposed KLM/Air France merger, its fellow members of the SkyTeam alliance. In September 2003 Alitalia signed bilateral partnerships with both KLM and existing partner Air France, as well as a trilateral partnership agreement.

These agreements set out possible future co–operation between the three airlines, including Alitalia joining the merged KLM/Air France — but this depends on improvement in Alitalia’s financial performance (hence the Industrial Plan) and, equally crucially, further privatisation.Currently, the Italian government holds 62.4% of Alitalia’s equity. Berlosconi has promised his French counterpart that the privatisation of Alitalia will be accelerated and in November 2003 the Italian government started the formal legal process to further privatisation through the issue of a "draft decree" that would allow the government to reduce its stake to below 50%. This would occur through a stock market offer or trade sale, though unconfirmed reports state that the Italian government may roll its stake into a joint holding company set up by Air France and KLM. No timetable has yet been released for the privatisation, although it is likely to happen in 2Q or 3Q 2004.

AZ/AF/KL?

Once Alitalia gains full independence from the government, then it will immediately enter into negotiations with KLM and Air France on ways Alitalia can integrate itself into the other two.

In the UK’s Financial Times, Mengozzi said: "It will be highly beneficial if we are able to catch the train at the second station. KLM and Air France could be the first station.

What is important is that we take the train, and that the train arrives at the right destination." But before Alitalia can catch that train — and secure its future — not only does the Italian government have to fulfil its pledge to reduce its stake but there also has to be serious progress to cutting costs as laid out under the Industrial Plan.

These are not inconsiderable barriers, and perhaps more so because KLM and Air France may have different viewpoints about how and when Alitalia will link with them.

The relationship between Alitalia and Air France is close, encouraged by a code–sharing deal began in November 2001 and cemented by the completion of a long–planned deal in January 2003 when Alitalia paid €53m for a 2% stake in Air France.

In January 2004 the two airlines also announced that they would split services between Italy and France, with Alitalia operating Air France flights between Milan Malpensa and Paris CDG, and Air France taking over some of Alitalia’s routes to France from regional airports.

On the other hand, KLM is wary of committing itself to an equity deal with Alitalia given that the previous partnership signed between the two in 1998 (which was also supposed to lead to a merger) was unilaterally terminated by KLM in 2000 amid rancour about the then delay in privatisation as well as problems with Milan Malpensa airport.

Alitalia and KLM each wanted compensation from the other, and in the end a tribunal ordered KLM to pay Alitalia €172m compensation.

Naturally, both airlines now insist this disagreement is behind them, but KLM and Air France will want to be sure that Alitalia is financially and operationally sound before they allow their SkyTeam colleague to enter the merger. Overall, it is difficult to argue against the view that Alitalia needs KLM/Air France much more than KLM/Air France needs Alitalia.

And then there are the regulators. There is already concern from other airlines at the existing partnership between Alitalia and Air France — in December 2003 Alitalia and Air France offered to release slots on seven routes between Italy and France in order to get formal European Commission approval for their partnership. The EC is concerned about competition on the major routes between the Milan, Rome and Paris hubs and, according to easyJet, Alitalia and Air France provide more than 80% of capacity on the 10 largest routes between Paris and Italy.

Not surprisingly, easyJet has called for the two airlines to hand over a substantial amount of slots to reduce their dominance.

Much therefore stands between Alitalia and its long–term survival. But if Alitalia sorts out its cost base and if the Italian government divests its controlling stake and if KLM is amenable to an Alitalia entry into KLM/Air France, then Alitalia’s future would be secure.

Cocooned in the safety of a European mega airline, the former Alitalia’s brand and assets would have to undergo drastic pruning and reorganisation — but at least "Alitalia" will survive — whereas a standalone Alitalia, jettisoned by the Italian government, would be fated to terminal decline.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | ||||||

| Alitalia | ||||||||

| A319 | 9 | 3 | ||||||

| A320 | 10 | |||||||

| A321 | 23 | |||||||

| 747-200F | 3 | |||||||

| 767-300ER | 13 | |||||||

| 777-200ER | 8 | 2 | ||||||

| 777-300ER | 6 | |||||||

| MD-11 | 3 | |||||||

| MD-80 | 89 | |||||||

| Total | 158 | 5 | 6 | |||||

| Alitalia Express | ||||||||

| ATR-42 | 2 | |||||||

| ATR-72 | 10 | |||||||

| Emb-145 | 14 | 7 | ||||||

| Emb-170 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Total | 26 | 6 | 13 | |||||