US legacy carriers fight back

February 2004

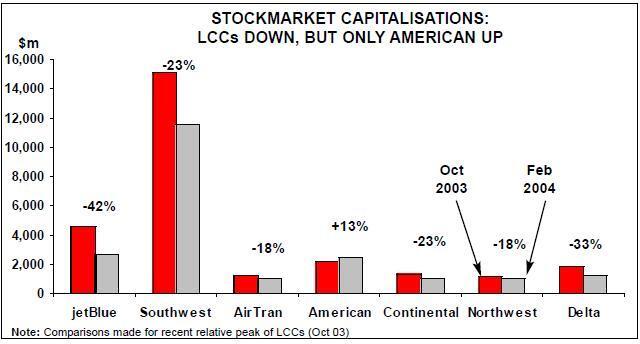

The past three years have seen low–cost carriers (LCCs) rise rapidly at the expense of the legacy airlines in the US. Many people have expected this trend to continue in 2004 and beyond, with the likes of JetBlue, AirTran and Frontier capturing an ever–increasing share of the US domestic market.

After all, those carriers have healthy profits, strong balance sheets and aggressive growth plans, whereas the large network carriers continue to lose money and are handicapped by weak balance sheets and heavy debt and pension obligations.

However, it has never seemed very plausible that the legacy carrier sector would simply fade away, particularly in light of all the cost cutting and restructuring that has been accomplished or is under way. Legacy carriers still account for about three–quarters of total US domestic capacity (ASMs).

Indeed, recent weeks have seen growing evidence suggesting a change in the competitive dynamics in the industry. After three years of market share erosion, the large network carriers could (at least temporarily) recover some ground in 2004.

Three new developments support this assertion. First, the US legacy carriers are suddenly responding aggressively to the LCC threat. This is taking the form of both general capacity addition — aggregate ASMs are up significantly in 2004 — and competitive moves in specific markets.

Both the overall scale of new competitive activity by the major airlines and the scope of some of the individual actions are unprecedented. By most estimates, they will have some impact.

Second, the message coming across loud and clear from the latest round of airline earnings conference calls and other recent announcements is that, except for US Airways, the large US network carriers are in better shape financially than what many had expected.

(Of course, they still face many challenges.) In contrast to the situation last year, the legacy airlines actually look like survivors — something that may also explain their new–found aggressions. They are benefiting from strong liquidity positions and improved access to the capital markets, as well as significantly reduced cost structures in some cases (American and United).

Therefore, even if they do not yet have the cost structures to sustain the most extreme pricing actions, they now have staying power.

Third, in recent months LCCs' profit margins have come under pressure from escalated competition and low yields in transcontinental markets, where much of their recent expansion has focused. Most notably, JetBlue’s fourth–quarter operating margin (13.3%) fell several percentage points short of its original forecast and the year–earlier figure.

No–one is seriously worried about small margin reductions (JetBlue’s margin was still the best in the industry) but, rather, whether they are a sign of worse things to come. Will LCCs see sharper profit margin declines when they expand more in the low–yield transcontinental markets and as competition really heats up on the East Coast? Could they even be forced to curb their growth plans?

All in all, after essentially having the playing field to themselves for three years, LCCs like JetBlue, AirTran and Frontier face tough new challenges in 2004. It will be interesting to see how those airlines, known for their creativity, will respond. Will their growth strategies change?

It has to be stressed that there are no concerns about the oldest and largest LCC, Southwest, which is accelerating growth significantly this year and in 2005 (Aviation Strategy briefing, January 2004). Its Philadelphia expansion from May could have devastating impact on US Airways.

Southwest is almost as large as all the other US LCCs combined — last year its domestic capacity share was 11.5%, compared to 14.4% for other LCCs (including America West). Therefore rapid growth at Southwest will keep the total LCC capacity share expanding even if some of the smaller carriers needed to pause to reassess their strategies.

Of course, because the US domestic revenue e n v i r o n m e n t appears to have changed permanently, all airlines — whether they fit neatly into today’s "LCC" category or should perhaps be described as "reformed legacy carriers" — will need relatively low cost structures in the future.

Why the legacy carriers look stronger

The legacy carriers have managed to build their cash reserves to record levels. This is as a result of the following: large federal security cost refunds in the spring of 2003, successful cost cutting and restructuring, positive or vastly improved operating cash flow (particularly in the past two quarters), "cash is king" attitudes and, above all, continued ability to raise more debt.

AMR, which had a close brush with Chapter 11 only nine months ago, has just raised well over $500m in the capital markets in two separate transactions — a $222.5m EETC–type private offering secured on aircraft spare parts and a $300m public convertible bond offering. For the latter, it was able to secure a mere 4.5% interest rate.

The proceeds have bolstered AMR’s already strong liquidity position ($2.6bn in unrestricted cash at year–end) and made its substantial ($1.9bn) 2004 cash obligations look perfectly manageable.

The $1.8bn annual labour concessions secured on the courthouse steps, as well as the $2.2bn–plus of other cost savings, have given American the lowest unit costs among the large network carriers. Its 4Q CASM was 9.45 cents or 12% below the year–earlier level.

On an annualised basis, such a decline would have given it CASM of 9.50 cents in 2003. But American is now targeting an even bigger 17% CASM reduction in the current quarter.

AMR remains highly leveraged, with total debt and leases of $21bn and a net lease adjusted debt–to–capital ratio of 100%.

However, it is worth noting that it has already managed to modestly pay down debt by redeeming $305m of airport bonds in the fourth quarter.

United has used the Chapter 11 process to substantially reduce its cost gap to the LCCs. Its CASM fell by 17.3% to 9.85 cents in the fourth quarter; on an annualised basis the 2003 CASM would have been 9.40 cents (similar to American's). Total cash reserves at year end were an adequate $2.4bn, including $679m of restricted cash.

Significantly, United secured a commitment for $2bn of Chapter 11 exit financing, including $400m in non–guaranteed funding, from JPMorgan and Citigroup in mid–December.

It has resubmitted its loan guarantee application to the ATSB and still hopes to emerge from bankruptcy this spring or summer. However, it is hard to predict its chances because some tough issues remain unresolved, including pension funding, retiree medical benefits, United Express strategy and municipal bond litigation.

In recent years Continental has consistently outperformed the other legacy carriers and has enjoyed the lowest CASM, mainly due to a labour productivity advantage. But it has now lost almost all of its cost lead over American and United. Nevertheless, in the short term it is adequately positioned with CASM of 9.36 cents (2003); the aim is to hold it at 9.30–9.35 cents in 2004. Year–end cash reserves were $1.6bn, of which $170m was restricted.

Delta and Northwest need to lower their labour costs to remain competitive. Both are talking to their unions but making slow progress. UBS analyst Sam Buttrick made the point recently that both airlines would almost certainly obtain the necessary savings (without the threat of bankruptcy, which was no longer an effective tool) but that he could not predict the timing.

Further delays on the labour front would mean Delta and Northwest continuing to post sizeable financial losses in 2004. The other large network carriers (except US Airways) are currently expected to return to marginal or modest profitability this year — even at the current level of fuel prices.

The big positive for Northwest is that when it eventually adjusts its wage rates, its CASM is likely to be at the low end of the legacy carrier range. Its 2003 CASM of 9.76 cents (excluding special items) already reflected relatively low non–labour costs.

Northwest has raised unsecured debt on several occasions over the past year, though last month’s $300m offering incorporated an unattractive 10% interest rate. The financings have helped Northwest maintain the strongest liquidity position relative to size among its peers (unrestricted cash of $2.76bn at year end).

The company will need continued access to the capital markets to meet its substantial cash obligations this year and in 2005.

Delta’s financial recovery is expected to significantly lag behind its peers, which the airline blames squarely on its pilot cost disadvantage.

Faced with the prospect that the talks could drag on into 2005, and with CASM of 10.48 cents in 2003 (the second–highest after US Airways), the airline continues to focus heavily on cost cutting. Substantial upcoming debt maturities and pension obligations are also a point of concern.

Nevertheless, Delta is not considered a potential Chapter 11 candidate because of its strong liquidity ($2.7bn in unrestricted cash at year–end) and continued ability to tap the capital markets. It has just raised $325m through a private placement of convertible bonds.

Of course, the "new benchmark" CASM level of low–to–mid 9s will not make the legacy carriers truly competitive with the LCCs for the longer term. The airlines are not keen to divulge their ultimate CASM targets, but Northwest executives suggested recently that low–8s was a reasonable long–term goal for the type of revenue environment that exists today.

Legacy carriers' competitive actions

American set the tone in early January with an unusually aggressive fare offensive targeted at JetBlue, to mark the latter’s debut in Boston.

The major airline is offering a free return ticket anywhere in the world to AAdvantage FFP members who fly two round trips in selected Northeast–Florida or Northeast–California markets that JetBlue serves before April 15. Delta and United have more or less matched the offer.

Those deals represent unprecedented bargains for travellers, also because they can be combined with other special offers (such as $69 fares to Florida). They are in an entirely different league from the previous practice of the majors just matching LCCs' fares and maybe offering double or triple FFP miles.

American is now unleashing the power of its massive FFP and worldwide network more effectively in competition with LCCs. It will be giving away a lot of seats, but the award trips will be spread over 12 months and have fairly significant restrictions. Overall, it is probably a shrewd move in the current industry environment.

Delta’s main response to LCCs has been to launch its own low–fare unit, Song, as a successor to Delta Express (April 2003). Song has targeted JetBlue directly with its East Coast network and upscale product. It has grown rapidly to a 36–aircraft operation. However, last month Delta put Song’s expansion on hold subject to a "full strategic review" of all aspects of Delta’s business plan, initiated by new CEO Gerald Grinstein after taking office in early January.

That said, it is also obvious that Song has not lived up to expectations. According to a recent comparative analysis of O&D data by Raymond James analyst James Parker, JetBlue has outperformed Song by a huge margin in the four JFK–Florida markets served by both airlines in 3Q03. Song’s load factor was 58%, compared to JetBlue’s 82%. Song’s average fare ($80) was $20 lower than JetBlue’s. Song had a negative 65% margin in those markets, compared to JetBlue’s positive 20% margin. (The comparison did not include Song’s connecting passengers at JFK or revenues from its on–board sales of food. Also, Song is now substantially larger.)

News of the hold decision on Song boosted JetBlue’s share price, but it was not necessarily a favourable development from LCCs' point of view. Now Delta may well end up doing what many people have always said it should have done in the first place, namely reduce costs across its entire system.

It is also possible that, as Delta has frequently claimed, Song has helped it identify new efficiencies for the rest of the network, such as ways to shorten aircraft turnaround times. If so, the venture has not been a total failure.

Separately, in late January Delta announced plans to strengthen its JFK operations over the next eight months. Between mainline, Song and Delta Connection, there are plans to add eight new destinations and 14 additional daily flights in existing markets out of JFK, as well as invest $300m to upgrade systems and processes.

The competitive implications are twofold. First, Delta’s move is a direct attack at JetBlue’s JFK home base. Second, it will add a big chunk of capacity to the transcontinental market, where fierce competition among newcomer LCCs and established majors has already driven one–way fares as low as $79.

United is launching its new low–fare operation, Ted, on February 12 at its Denver hub.

The unit will serve initially eight leisure destinations out of Denver, plus the West Coast from Las Vegas and Phoenix. It will be a one–class operation, with a simple fare structure. The plan is to utilise 45 A320s by the end of 2004, of which 19 would be based in Denver.

In early February United did its bit to add to the East Coast frenzy by announcing plans to bring Ted to its Washington Dulles hub in early April. It will serve three Florida cities and Las Vegas, operating 15 daily round trips by mid- May (22% of United’s domestic mainline flying out of Dulles).

Of the LCCs, Denver–based Frontier will potentially feel the biggest impact from Ted. However, Frontier is convinced that in sub–stance Ted does not represent anything new. United is not adding much capacity — it is replacing mainline capacity with Ted capacity, utilising slightly larger aircraft. Only one of the initial Ted markets, Ft. Lauderdale, is a new market not served by United. The major carrier has always matched Frontier’s fares — as does Ted.

At Dulles Ted’s role will be to defend United’s position against Atlantic Coast’s planned low–fare hub operation, Independence Air. ACA is still waiting to be released from its United Express feeder contract, so that it can launch independent operations with RJs and A320s later this year. Ted will have a head start of at least six months, but in the end its relatively small presence may not have much impact on ACA’s plans.

ACA hopes to quickly build the Independence Air operation to 350 daily flights to over 50 destinations on the East Coast, the Midwest and the West Coast.

United is reportedly claiming that Ted will achieve 15–20% lower CASM than mainline through simplified operations, higher utilisation and 18 additional seats on the A320s. However, except for the dedicated fleet, Ted will be part of United, with less of an independent brand than Song has.

It is hard to see what United could possibly accomplish with Ted that could not be done with the mainline operation (which now has relatively low CASM). Or, as James Parker put it in a recent research report: "Why do this when United’s entire domestic system is already low fare?"