Network carriers: service and coverage without the cost penalty

February 2003

Booz Allen Hamilton* consultants have addressed the very pertinent question of how network carriers could re–invent themselves to achieve the profitability levels of successful low cost carriers.

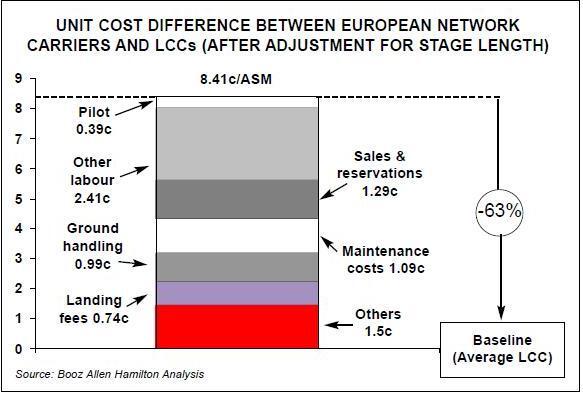

The cost gap between full–service hub and spoke (H&S) airlines and the low cost carriers (LCCs) on both sides of the Atlantic is striking (see chart below). Cost differences exist across the board: pilots, on board services, sales and reservations, maintenance, aircraft ownership, ground handling. This is not simply a matter of LCCs paying lower salaries or using cheaper airports; rather it is a function of fundamental differences in the two airline business models.

LCCs have successfully designed a focused, simple operating model around nonstop air travel to and from high–density markets. H&S carriers, on the other hand, support a highly complex system of operations. Their business model is predicated on offering consumers a broad range of destinations, significant flexibility (ranging from last–minute seat reassignments and upgrades to complete itinerary and routing changes), and frills (speciality meals, lounges, in–flight entertainment, etc.).

This model builds in the cost penalties of synchronised hub operations (long aircraft turns, slack built into schedules to increase connectivity), and so implicitly accepts a slower business pace to accommodate continuous change.

In addition, the H&S business model relies upon highly sophisticated information systems and infrastructure to optimise its fundamental value proposition: to take anyone from anywhere to everywhere… seamlessly.

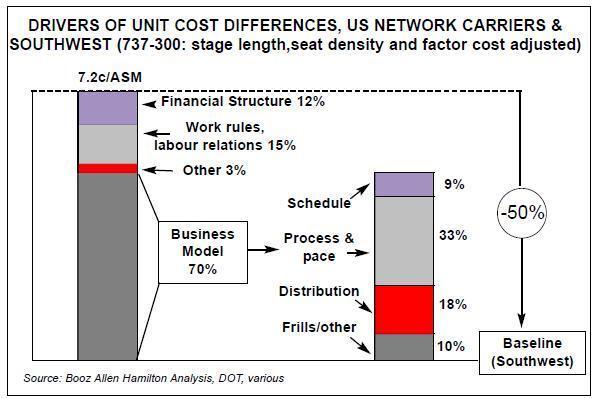

The chart on page 16 breaks down the cost differences between the H&S and LCC business models, using Southwest and the US network carriers as examples. To isolate business model effects, the comparison has been performed for 737–300s and been normalised for differences in labour rates, fuel prices, aircraft configurations, and stage lengths. Even so, the 2:1 cost differential persists.

Some 70% of the difference can be attributed to explicit business model choices; another 15% percent to work rules and labour agreements; and 12% to differences in balance sheet structure and financial arrangements.

Of the 70% attributable to business model differences, the largest contributing factors by far are business pace and process complexity, and distribution cost differences (which are narrowing with the elimination of commissions).

A remarkably small proportion of the cost differential is "frills"-related. In fact, the "no frills" and "full service" labels are misleading in describing LCC and H&S carriers. It’s the relative simplicity or complexity of their business models that distinguishes them.

LCCs' growth potential

The growth of Southwest in the US over the past three decades sheds useful light on the growth and development of the LCC business model. Initially a low–cost, point–to–point Texas carrier, Southwest has broadened its original market focus and stretched its business model.

It has steadily and profitably expanded across the country, extending its service offering to the point where it now provides connections through pseudo–hubs and non–stop transcontinental flights. In its established markets, Southwest tends to have a frequency advantage over network carriers and is widely accepted among business travellers who value its efficient, reliable service.

Today, Southwest competes effectively in other airlines' hub markets and participates on a non–stop basis in a range of small markets (below 100,000 passengers per year).

We estimate that a quarter of its revenues derive from passenger trips over 1,000 miles, and more than 5% comes from trips over 2,000 miles.

Significantly, Southwest has managed to add "network" features to its point–to–point business model without incurring most of the associated complexity costs.

By Booz’s estimates, LCCs could potentially participate in more than 70% of the US domestic market. The only sectors which provide H&S carriers appreciable protection are smaller "connect markets" that cannot be reasonably serviced on a non–stop basis (about 20% of the US domestic market) and longer haul markets, where on board services are more prized and the cost differential is smaller (about 10% of the market). This projection is not meant to suggest that Southwest and its peers will take over 70% of the market. It does, however, mean that prices will continue to fall as LCCs penetrate further, undermining the profit engines of traditional carriers. Southwest typically prices 50% lower than incumbents in the one to two hour markets it enters, reducing the price realisation of traditional carriers in those markets by 25 to 35%.

It is the LCCs' impact on overall price levels — not the loss of traffic — that poses the real threat to traditional H&S carriers. LCCs actually stimulate significant new traffic as they enter a market.

But they also bring down price levels, and those price pressures manifest themselves in a broad range of markets: in local markets to and from the hub, in shuttle markets, in connecting markets, and in adjacent markets (those not directly served by the LCC, but available via ground transportation).

As long as LCC penetration is limited, H&S carriers can compensate for these revenue pressures by leveraging "network effects" — by focusing on connecting flows and new destinations not yet served by LCCs.

However, as LCCs expand both their geographic scope and service offering, it will become gradually more difficult and expensive to coexist. Over time, LCCs will serve more destinations, operate from a broader range of airports, and participate in more traditional connecting markets, either with their own one–stop service or by over–flying the hub.

H&S carriers, meanwhile, will find it more and more difficult to subsidise exposed traffic flows with profits earned in their remaining protected markets, including intercontinental traffic flows.

The challenges facing H&S airlines are further complicated by the fact that there are too many hubs and too many airlines. In the US, no airline provides a comprehensive nationwide service despite the network of hubs at its disposal, and no European carrier has expanded appreciably beyond its own national borders.

The result has been a proliferation of smaller hubs in "secondary" markets on both continents to provide network breadth. There is probably nearly twice as much connecting capacity in the US as the underlying market requires. Large numbers of passengers travelling between major cities that already have, or can support, non–stop service still opt to take connecting flights, motivated by price or loyalty programmes. It is not just the intercontinental passenger, or those travelling to or from small communities, that connect through the hubs.

Indeed, the US market is so fragmented that 60 to 80% of most carriers' traffic is exposed to instant price competition (see chart below). H&S carriers compete aggressively in connecting flows and in leisure markets, where they price "for contribution," well below fully allocated costs. In these markets, an excessive number of hubs compete for traffic and trash prices, creating a hyper–competitive environment. Only some 20 to 40% of revenues come from local business markets where the airline is comparatively advantaged and protected from other H&S carriers. This is where profits (if any) are realised.

In Europe, the situation is similar, although less severe. A higher proportion of revenues come from business travellers, and some of Europe’s connecting markets are less competitive.

That said, the European market can support only three, maybe four, intercontinental network systems. Until there is consolidation, weak and strong hubs will compete vigorously for scarce intercontinental traffic, pressuring the balance sheets of all players, not just the smaller and most vulnerable flag carriers.

Alliances have offered some relief, allowing carriers to furnish their loyal, high–yielding business customers with a more competitive product offering. Still, alliances have not enabled airlines to rationalise hubs, significantly restructure networks, or realise most of the cost and revenue synergies of full consolidation.

The prospect of unilaterally shutting down weaker hubs to eliminate excess connecting capacity is not an attractive one either.

Destination breadth would suffer, and many elements of the fixed–cost base would not go away. Moreover, aircraft could not be economically redeployed to other markets at current cost levels.

The continued growth of LCCs will only exacerbate these problems as they undermine the revenue generation potential of existing hubs (especially in the eastern US and Europe), increase price competition in both local business and connecting markets, and convert existing connecting markets to non–stop status.

Precious few markets will be immune.

A new operating model

To continue to operate in this competitive environment, H&S carriers need to overhaul their business systems to move costs within range of the LCCs and reduce their sensitivity to economic and competitive pressures.

To effect this overhaul, US carriers must urgently restructure their core operations. Labour concessions are only a starting point; they are necessary but not sufficient to overcome the cost disadvantages of a H&S business model.

The key to effectively restructuring an H&S airline’s core network is implementing a lower cost structure business model without giving up the critical service and coverage attributes prized by high–value customers. Ideally, this restructuring would increase the product differentiation between high and low priced services and would occur in conjunction with network changes.

The experience of other industries — automotive assembly, certain heavy manufacturing, increasingly in financial services — that have executed fundamental business model changes yields important insights:

- To be successful, companies must reconfigure the product or service so that structural barriers to efficient operations are eliminated.

- The "product architecture" (how the product is assembled or produced) needs to be broken down into distinct business streams so that commonalities are maximised, and the differences contributing to process complexity are minimised within each stream. The objective is to isolate the 80% of processes that are routine and unchanging from the vicissitudes of the 20% that change with each iteration.

- Significant cost improvement then comes from "tailoring" each of these business streams. For example, an airline might industrialise its approach to the 80% of its activities that are routine (like domestic leisure travel), while upgrading the resources devoted to complex activities that are ever–changing like last–minute re–routing of business passengers).

TBS approach

The governing principle in this kind of restructuring — Tailored Business Streams (TBS) — is not a new concept; it has been applied to parts of the manufacturing industry for some time. The essence of the approach is to reduce the cost of complexity, not necessarily to reduce the level of complexity. That said, many TBS initiatives result in the elimination of self–induced complexity (last–minute seat changes, overbooking) and restrict customer–driven complexity to those areas where it actually adds value.

The applicability of the TBS approach to the airline business model is striking. Many of the cost penalties inherent in the H&S system are associated with its complex business processes and slower business pace, rather than with the "frills" it offers travellers.

Southwest has amply demonstrated that these complexity costs don’t have to be. An airline can provide some of the benefits of the H&S system (high frequency levels, long–haul flights, connections) without incurring many of the H&S costs.

This does not imply H&S employees don’t work hard (although productivity could be improved among certain labour groups), but that extraordinary manpower is required to execute relatively simple tasks. Network carriers have designed their infrastructure and business systems for the most complex requirements.

This sophisticated business system is then utilised for all activities, complex or simple. By tailoring business streams and redesigning how services are provided, we believe that it is possible to eliminate much of the H&S cost penalty (70 to 80% for leisure travel) without eliminating many of the attributes that consumers value. What does this mean for H&S carriers? It means they may have to:

-

Remove the scheduling constraints to much higher asset and personnel utilisation H&S airlines today accept the slow turns and scheduling inefficiencies of connecting bank structures. A network designed around the needs of profitable, local passengers would eliminate these scheduling barriers and enable a significantly faster business pace. This may require rolling hubs and longer, more random connections. Local market services may well improve, especially as costs are lowered, although carriers would likely experience some share loss in the less profitable large city connecting markets. Increased connect times should not prove much of an issue in intercontinental and small community markets.

-

Create separate business systems for distinct customer and product segments At the extreme, this might mean separate aircraft and airports for business and leisure travellers. At a minimum, it would involve a high degree of process and product separation, reflecting the different underlying values and needs of distinct market segments.

-

Tailor business streams to the needs of each customer segment The key element is to industrialise and simplify all the handling processes for routine work, especially leisure travellers, where the discrepancy between "customer requirement/willingness to pay" and "capability/cost" is the greatest. The objective should be to increase productivity dramatically — by as much as three times at airports–and virtually eliminate all costs associated with change, complexity, and multiple handling. This undertaking will require significant alterations in service policies, distribution approaches, systems, and processes. Ultimately, the air travel product should be so tailored to leisure traveller needs that airport processing is minimal; the vast majority of passengers will not need or want to change anything at the last minute. Moreover, the check–in process will be so intuitive that infrequent travellers can navigate the airport without significant hand–holding.

As for tailoring the business traveller stream, carriers should focus on streamlining processes to the greatest extent. Most business travellers simply want to get through the system reliably and quickly with minimal staff interaction.

Of course, this business stream will still need to accommodate the ever–changing schedules of business travellers, a source of complexity that will not go away. The trick here will be to streamline these change activities as well, so that they are as automated and simplified as possible.

This would also allow more resources to be devoted to the services the business traveller’s value. Finally, airlines will need to dedicate special processing line(s) to deal with true exceptions and extraordinarily complex matters.

-

Increase the pace of all operations This should be the natural result of the above changes, but time compression will further flush out remaining inefficiencies in the system. As in other industries, the degree of sophistication and level of cost tend to be determined by the available time rather than the underlying need — manpower costs are driven by how long the plane is at the gate or a station is manned.

In sum, the industry’s major H&S carriers need to design and adopt a new business model, whose "objective function" is to eliminate the costs of complexity and provide a more differentiated service between customer/product segments. They can accomplish this goal by designing processes that reflect the simple needs of the vast majority of customers, while focusing discretionary expenditures on those areas where they add consumer value and contribute to the bottom line.

Looking Ahead

So far, no airline has undertaken a restructuring of this magnitude. It is a bold journey that will require the complete commitment of the airline’s current and future leaders. To effect changes on this scale, executives need to abandon many of the tenets that have guided the industry for the past 20 years. While there are many lessons that other industries have learned as they embarked on this journey, a few stand out:

- This is a clean–sheet redesign requiring a fundamentally new mind–set. Incremental moves will not get traditional carriers where they need to be.

- The results are multiplicative. Pursuing a single dimension (like rolling hubs) without simultaneously addressing other aspects of the business model will yield insufficient results. All the airlines that have rejected de–peaking have discovered this. On their own, schedule changes will have limited impact. The benefits come when processes are redesigned to capitalise on the higher pace.

- Changes will be system–wide and cascading from reservations to front–line staff functions to systems and from reservations to front–line staff functions to systems and infrastructure. While the resulting product may be no less complex, the organisation delivering it will be much more streamlined.

- Existing organisations will resist the change. Airlines will need to expend as much, if not more, effort driving the change process as they put into designing the solution.

- The risk of inaction is much greater than the risk of acting and getting it wrong. The first airline to recognise the need for fundamental business model change will be able to shape the new competitive landscape. The prize that awaits first–comers is significant, not just in terms of lower costs, but also in growth opportunities.

| Degree of Price Sensitivity | Non-Stop Passenger Flight |

Connecting Passenger Flight |

|---|---|---|

| Low: Individual chooses airline, travels on business or rich personal travel | 20%-30% of revenue | 20%-25% of revenue MODERATELY VULNERABLE |

| Medium : Corporation is principal decision-maker, drives bargain | 10%-15% of revenue MODERATELY VULNERABLE |

10%-15% of revenue VULNERABLE |

| High: Mostly leisure travel and price-sensitive business | 15% of revenue VULNERABLE |

10%-15% of revenue VULNERABLE |

| Generally product advantaged vs. other hub and spoke carriers | Product parity or disadvantage vs. other hub and spoke carriers |