Emirates: taking risks in going global?

February 2003

Emirates, the national airline of the United Arab Emirates, has enjoyed steady growth since it was launched in 1985.

Now however, it is launching routes to the only continents it has never served — North and South America — and has placed ambitious orders for new aircraft, including the A380.

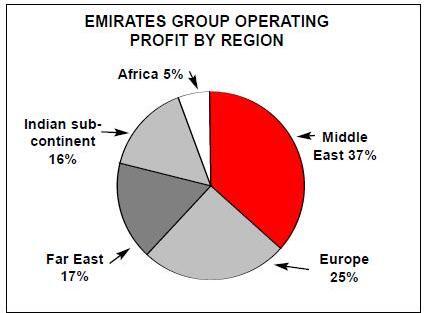

Can the Dubai–based airline continue its record of success, or is its single–minded focus on global expansion a risky strategy? Since being founded by the government of Dubai in the 1980s, Emirates' growth has come in parallel with the rise of the UAE as a key trading centre in the Middle East as well as the development of Dubai as a major tourist destination. It has also exploited its geographical position along major east–west air routes, and 50% of the airline’s passengers are in transit beyond Dubai. The attraction of Dubai as a stop–over makes transit/transfer strategy viable.

Today, the airline has established itself as a well–managed and successful international airline. With just under 9,000 employees, it currently operates to 58 destinations in 41 countries, and has a fleet of 44 aircraft.

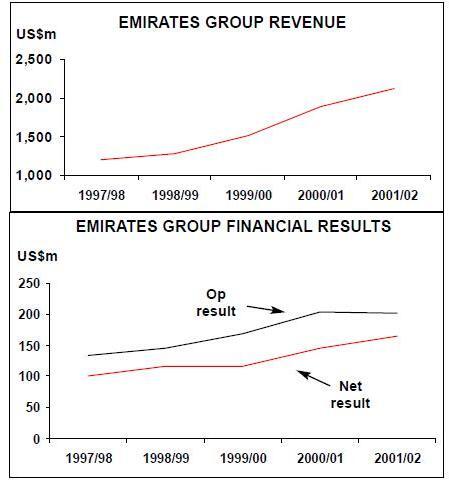

In November 2002 the Emirates Group (which also includes Dnata, an aviation services company which acts as GSA in Dubai and has the ground handling monopoly at the airport) announced net profits of US$110m for the first–half of the financial year (April–September 2002), compared with a US$45.7m net profit in the first–half of 2001/02. Operating revenue increased 27% to US$1.2bn over the same period, and cash reserves as at September 30 2002 were US$1.1bn, compared with US$763m a year earlier. The passenger load factor rose from 74% to 78% in the period, even though capacity was up 18%.

This is a considerable achievement given the effects of September 11. At the time, Emirates was immediately hit by the collapse in traffic, and in the short–term it suffered from the perception that Dubai was too close to Afghanistan to guarantee the safety of flights. But traffic recovered relatively quickly, although ironically — given its current expansion plans — one of the reasons it did so was because it did not have any exposure to the North American market.

Although costs were cut by around 5%, Emirates avoided taking the more drastic action that some of its rivals were forced into. For example, Emirates did not make any redundancies, but instead imposed a recruitment freeze. As for its route network it "marginally reduced" its schedules.

Overall, recovery from September 11 has been remarkable when compared with airlines in the West. As has Dubai’s tourism industry: despite a severe dip after September 11, tourism to the Emirate was up 6.5% to 3.6m visitors in 2001, with a further increase of around 10% predicted for 2002. The official target for 2010 is 15mtourists.

Industry rumours attribute Emirates' success to covert government support. This charge annoys the airline’s management who state that the airline only ever had US$10m in investment from the government, back in 1985, and that ever since it has funded itself through its own resources. The real issue for Emirates is whether it can continue its avowed strategy of expansion without overstretching itself. Since 1985, on average the airline has doubled in size every three or four years, and even with a higher baseline the passenger growth rate since 1997 has been more than 16% per year. After such expansion, many airlines would have chosen to consolidate for a while — but not Emirates.

After adding routes to Casablanca, Perth, Khartoum, Osaka and Mauritius earlier in the year, in November 2002 Emirates announced plans to increase frequencies on 17 routes, boosting total capacity by more than 20%, it claimed. It is also launching new services to Kochi in India (December 2002), Lagos (March 2003), Moscow (July 2003) and Shanghai (August 2003), all using A330- 200s, the mainstay of its current fleet.

Daily non–stop flights from Dubai to Sydney will start in October 2003 following the first deliveries of the ultra long–range A340–500. At about the same time Osaka will also be added to Emirates' network.

But the most strategic move comes with the launch of its first routes to the Americas.

Following a final agreement between the US and UAE governments on open skies, signed earlier in 2002, in August Emirates applied to the US Department of Transportation for permission for routes to New York and San Francisco. A daily service to JFK is scheduled for April 2004 with San Francisco to follow in the summer of that year. Both routes will use A340–500s.

Beyond those cities, a route to Los Angeles may also be added, and other destinations are under consideration.

After North America, Emirates' management will turn its attention to the last remaining continent not currently in its route network — South America. Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Santiago are all possibilities for the first routes, which again will be flown with A340–500s. Economic turmoil in the region, however, may yet affect the timing of new routes, although Emirates' intention is clear.

But expansion will not stop even there. Emirates wants to substantially increase capacity on some of its shorter routes, and — together with the long–haul expansion — the airline is buying more than US$15bn worth of new aircraft to facilitate this growth.

Fleet expansion

Altogether, Emirates plans to almost triple its current fleet between now and 2010, and it is in the middle of a major aircraft buying exercise. The airline is currently talking to Airbus and Boeing about orders for up to 60 aircraft that it aims to place in the first half of 2003, although most of these will be confirmation of LoIs and MoUs flagged at the end of 2001 at the Dubai air show.

These include 25 777–200/300s, to be added to the existing fleet of 18 plus three confirmed orders. Subject to evaluation, all 777s may be of the 300ER version. Also likely to be confirmed are eight extended range versions of the A340–600, providing that Airbus agrees to launch this model. These would be used on long–haul routes to Australia and the US from 2005 onwards. An existing order for six ultra–long–range A340- 500s (which has just won its certification from the European Joint Aviation Authorities) will start arriving in April 2003.

The only "new" order is likely to be for more A380–800s, in addition to the existing firm order for 22 aircraft (with 10 on option) that was announced in 2001 — although it is possible that any new orders here will be conversions from the 10 options already signed with Airbus.

Becoming a launch customer for the A380 was a giant step for Emirates, putting it in the same premium customer league as Singapore Airlines. In forecasting demand for the A380, Emirates appears to be assuming a continuation of its historic traffic growth and a continuation of restricted bilateral regimes as well as severe slot restrictions at airports like Heathrow.

Emirates may be particularly looking at routes to the Indian sub–continent, where continuing restrictive bilaterals in a lucrative market necessitate capacity increases through larger aircraft, rather than by adding frequencies.

If the aircraft operate at high load factors, as planned, then Emirates will achieve significant costs savings per passenger kilometre.

If those forecasts are wrong, then Emirates will have a lot of costly 540–plus seat A380s on its hands. Two of the A380s on order, however, are freighter versions, as cargo is an area of operations the airline is looking to expand (17% of revenue in 2001/02 came from cargo).

Emirates currently wet leases a 747–400F from Atlas Air on routes to Hong Kong and Amsterdam, but is also in talks with Boeing about possible development of a cargo version of the 777.

As well as the US$15bn–plus cost of the aircraft there are engine costs, infrastructure improvements, training costs etc. Already Emirates has announced it is investing US$275m in building a maintenance hangar at Dubai, which will service the A380s that will start arriving in 2006. On the other hand, Emirates will be greatly helped by the Dubai government’s US$2.5bn investment in expanding Dubai airport, which will be completed by 2006, without environmental inquiries.

Financing of such large orders will come from a variety of sources, including cash reserves, bond issues and various types of leases. The latter may include Islamic leases, which Emirates has already used for some aircraft and which comprise rental payments and balloon payments instead of regular principal and interest payments, which are not allowed under Islamic law.

A global alliance?

If Emirates is to become a truly global airline, will it be tempted to join one of the global alliances, a move it has resisted up until now?

Emirates has linked its frequent–flyer programme to the FFP of Singapore Airlines, a member of the Star alliance, but according to CEO Maurice Flanagan there is "no business case" for joining an alliance — a decision that would leave Emirates as the only global airline not to do so.

Instead it prefers to code–share, and has current agreements with, among others, Thai Airways, Japan Airlines, British Airways and South African Airways. Air France could be the next code–share partner, on the Dubai/Paris route, and negotiations are being held at the present. If successful, they could lead to a tripling of Emirates services on the route, although discussions are believed to be slow and painstaking.

Emirates may well prefer code–sharing to investing in airlines, given the problems is has faced since buying a 42.6% stake in SriLankan Airlines (then known as Air Lanka) in 1998. At the time Emirates also signed a 10–year management contract, which included a clause that the national airline would have non–compete rights on selected routes.

Unfortunately, the then opposition party, the United National Party (UNP), opposed this agreement, and in the general election held at the end of 2001 the UNP became the country’s new government.

The UNP promised to review the entire deal, which had become a major political issue, to see whether it gave too much protection to SriLankan Airlines, thereby restricting the emergence of new competitors.

Emirates was "invited" for talks with the Sri Lankan government in May 2002, creating a situation that few at the airline could have envisaged back in 1998. Negotiations on changes to the original deal have not been easy, it is believed, and — according to a SriLankan source — Emirates has had to make major concessions. A MoU was supposed to be unveiled by the end of 2002, following further talks in November.

Emirates was also interested in investing in Air India in 2001, but it eventually pulled out from making a bid after showing initial interest. An outside possibility is an investment in Iran Air. Iran, with its oil reserves and large, educated population has huge potential when normal relations with the West are restored, which looks increasingly likely.

Financing and resourcing expansion

Financing its expansion appears to pose few problems at the moment — for example, the Group’s first bond issue in July 2001, for US$204m and arranged by HSBC and the National Bank of Abu Dhabi, was oversubscribed two and a half times and was closed at US$408m. A further bond issue may be arranged in 2003. But assuming finance is not a problem and that cost levels can be kept under control — which are big assumptions — it is the softer issues of management overstretch and keeping services levels high that may represent the greatest danger to Emirates.

Emirates is well known for its customer care and service levels, particularly in its premium cabins — although some of its business seating is regarded as cramped.

In 2003 Emirates will unveil major improvements to its products — seat pitches will increase and more space given to passengers by, for example, reducing seating in 777–300s from 380 to 330. Already, a $30m advertising campaign has been launched to proclaim the new "global" airline. But will expansion erode these service levels? New staff will have to be hired and trained, new facilities opened, middle management will have to be expanded — while all the time trying to maintain existing service standards.

It’s a risk that Emirates is prepared to take, although the reasons for the airline’s attempt to become a truly global carrier are not immediately apparent. Maurice Flanagan is surely close to retirement (he has spent some 50 years in the airline business), and it would be great for him to round off his years of success at Emirates with the final piece in the global jigsaw. But there is a more fundamental reason for increasing the pace of its expansion: oil.

Dubai, one of the seven kingdoms that make up the UAE, is fast running out of the money–spinning resource. The oil is forecast to dry out completely by around 2010, and by then Dubai needs to have fully developed major companies and industries that can bring in much–needed replacement revenues.

Large–scale tourism and trade was long ago identified as a key strategic goal for the kingdom, and the necessary infrastructure for tourist and business travellers is a robust airline. As the government of Dubai owns Emirates 100% (with no official plans for privatisation), its wishes "guide" the strategy of the airline, so by 2010 Emirates' aim is to be a truly global airline, securing the passenger flows that Dubai needs. Substantial profits for the national airline would be an added bonus. However, although the reasoning for expansion for the Kingdom of Dubai may be valid, the dangers of overstretching the airline are real, whether it is in management resource, service reliability or financing.

| Fleet | On order | Options | |

| 747-400F | 1 | ||

| 777-200 | 9 | ||

| 777-300 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| A310-300 | 1 | ||

| A330-200 | 24 | 5 | |

| A340-500 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| A380-800 | 0 | 20 | 10 |

| A380-800F | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 44 | 36 | 22 |