American Airlines: Et tu AMR Corp.?

February 2003

Until very recently, American looked like one of the US airline industry’s most likely long–term survivors. Its financial losses since the September 11 terrorist attacks may not have been materially smaller than United’s, but it had strong liquidity, a large pool of unencumbered aircraft and no significant debt maturities on the horizon. Most importantly, it has been able to continue to access the capital markets to raise liquidity, as it demonstrated with a $675m aircraft financing in late December.

However, investor confidence in American’s ability to pull through the industry crisis has plummeted in recent weeks. The stock price hit an all–time low on January 29 — a pitiful $2.85, down from a 52–week high of $29.20 — as the markets evidently began to treat the world’s largest airline as a likely Chapter 11 candidate.

While there are no near–term liquidity constraints, analysts now view American as "probably the most challenged of the solvent majors" (as Merrill Lynch’s Michael Linenberg put it). In other words, American is now considered more likely than Delta, Continental or Northwest to join US Airways and United in Chapter 11 within 12–18 months. (Of course, in the event of a war with Iraq, all of those airlines become potential Chapter 11 candidates.)

As another indication that American poses increased risk, both S&P and Moody’s recently singled it out for additional scrutiny. The agencies began reviewing American’s corporate credit and debt ratings in view of possible downgrades.

American’s prospects have worsened because of its continuing heavy losses, described by its leadership as "unsustainable", and lack of any sign of recovery. Also, as the company disclosed in its earnings conference call on January 22, there are new negative developments that — in the worst–case scenario at least — could lead to a liquidity crisis later this year.

First, as a result of heavy borrowing and a decline in aircraft values, AMR’s primary sources of backup liquidity (newer, Section 1110–eligible unencumbered aircraft) are diminishing.

Second, the company warned that it is likely to face debt covenant issues in the summer. If those issues are not resolved, as much as $834m of secured revolving credit facility debt would come due prematurely.

This would be in addition to about $800m of scheduled debt and capital lease payments and $300m of planned maintenance capital spending in 2003.

Third, like many other large US carriers, AMR faces hefty financial obligations in respect of the funding of its pension plans.

The company recorded a significant minimum pension liability at year–end, resulting in a $1.1bn charge to stockholders' equity.

In addition, there are concerns that various industry developments will harm American’s competitive position in the longer term. The biggest worry is that UAL will emerge from Chapter 11 as a lean and powerful competitor. Although it is early days yet, both UAL and US Airways appear to be making progress in tackling their unions and aircraft lessors in the bankruptcy court to obtain what could add up to significant cost savings.

Also, American has potentially the most to lose from a fully developed Continental- Delta–Northwest alliance. Since having the proposed code–shares approved last month, the three airlines are going ahead at full speed, even to the extent of ignoring the DoT’s conditions.

So what is American doing to try to stem losses and ensure a competitive position in the longer term?

Continued heavy losses

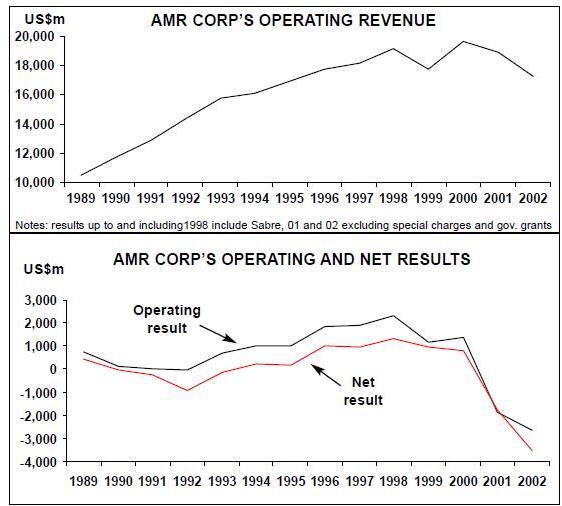

American’s parent AMR reported a horrendous $3.5bn net loss on revenues of$17.3bn for 2002.

It was double the 2001’s $1.8bn net loss and earned the dubious distinction of being the largest annual loss ever recorded by any airline (even exceeding the $2.1bn and $3.2bn net losses that UAL posted for 2001 and 2002, respectively). Excluding special charges, AMR’s net loss rose from $1.4bn to $2bn.

The December quarter’s $529m net loss was 28% lower than the year–earlier $734m loss before charges, but it was an easy comparison over the extremely depressed final months of 2001.

The heavy losses reflect the fact that American has been under–performing competitors on the revenue side.

In the fourth quarter, its system unit revenues (RASM) rose by only 2.6%, compared to an industry average increase of 5.9%.

The airline blamed this on its geographic mix, namely a heavy exposure to Latin America and certain US markets that have seen the biggest declines. Also, it has a small presence in Asia — a region that is now outperforming and helping competitors like Northwest and United.

Another problem is growing competition from low–cost carriers, which, by American’s estimates, were present in markets that accounted for 82% of its domestic traffic in the fourth quarter, up from 75% a year earlier. American might have been expected to benefit from some "booking–away from United" effect, given that the two share a major hub at Chicago O'Hare and compete directly in a large number of markets.

However, AMR’s CFO Jeff Campbell claimed that there had been no net benefit because of United’s price–cutting. He suggested that the media had done a remarkably good job in educating the public about Chapter 11, which meant that few Americans these days worry about flying bankrupt carriers.

American’s domestic RASM remained flat while international RASM rose by 10.4% in the fourth quarter. The latter was boosted by 19.6% RASM growth on European routes (from a very low base), mainly thanks to a 15–point load factor improvement.

Continental Europe has continued to outperform the UK market.

Like other major airline executives, Campbell reported that the revenue environment remained extremely weak. However, American may gradually catch up with competitors as it continues to adjust its network. Among other things, it is cutting capacity in the weakest domestic and Latin American markets and expanding service to Tokyo.

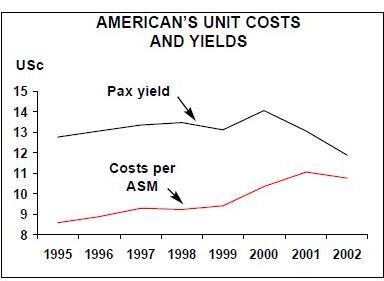

Although American’s cost performance in the fourth quarter was impressive, it nowhere near compensated for the decline in revenues since 2000. Operating costs were essentially flat and unit costs (CASM) fell by 5.3%, despite a 6.2% increase in capacity and 15% higher fuel prices.

The 7% reduction in ex–fuel CASM in the fourth quarter was driven by controls on discretionary spending and $2bn of cost–cutting initiatives. The main projects included de–peaking of the Chicago and Dallas hubs, fleet simplification and automation of ticketing and check–in. There were savings in commissions, aircraft rentals, facility rentals, landing fees and food and beverage costs.Unit costs are expected to fall by 1% in the current quarter, despite an anticipated 36% hike in fuel prices (a non–war scenario) and 1% higher capacity. The airline has hedged 40% of its fuel needs in the first quarter and 32% in full–year 2003, both at $23 per barrel — not the strongest of hedge positions.

Heavy losses are likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Based on traffic and cost trends but excluding any impact from a possible war with Iraq, AMR expects the seasonally weak March quarter’s pretax loss to be similar to the December quarter’s $828m loss, with daily cash burn still averaging $5- 6m.

More disturbingly, even under the non war scenario, AMR is currently expected to lose almost as much in 2003 as it lost in 2002; the late January consensus estimate was a loss before special items of $12.82 per share this year, compared to last year’s $12.97 or $2bn.

There is clearly a long way to go to get costs in line with revenues. American has identified the need to find another $2bn of annual structural cost savings, to bring the total to "at least $4bn".

Potential liquidity issues

AMR had $2.7bn in cash at year–end, after the addition of the $675m proceeds from the aircraft financing. The figure included $775m of restricted cash, of which $350m covered letters of credit backing certain facility bonds that the company plans to redeem in the near future (because they are using more cash collateral than the face value that they represent). The cash position is believed to be adequate for the near term, especially since AMR expects to receive its final tax refund (about $550m) in March. Also on the positive side, AMR’s pension problems seem lesser in magnitude than those faced by some other major carriers.

The company expects its total pension expenses to rise by around $250m to $700- 750m this year, but the cash contribution will only be about $200m.

Like many of the other majors, American has done a good job in reducing near–to medium term capital expenditure to a minimum. The latest significant actions on the fleet side, undertaken last autumn, included accelerating aircraft retirements, putting 42 aircraft into temporary storage from early 2003 until "at least 2005" and deferring deliveries of 34 additional Boeing aircraft in 2003- 2005. These and earlier measures shaved $4bn from AMR’s 2002–2003 capital spending plan, reducing last year’s spending to $1.8bn and this year’s to $1.4bn.

Of the $1.4bn total, $1.1bn is covered by prearranged financings of regional jets and Boeing aircraft. Boeing is providing full financing for all 11 new aircraft scheduled for delivery in 2003 (American had wanted to defer those aircraft too but was not able to).

This leaves just $300m maintenance–related capital spending to be paid for this year. On the negative side, there is the risk posed by the debt covenant violations this summer. American currently believes that it will be able to renegotiate the covenants relating to the credit facility, which is provided by a consortium of banks.

However, if the industry environment worsens, it may not be able to reach acceptable terms with the banks (for example, on the amount of additional collateral required). In such a scenario, it would have a significant $1.8bn burden of debt and capital lease payments to meet this year.

Another potential problem is that there are fewer attractive assets to put up as collateral. As a result of the December financing, AMR’s pool of unencumbered aircraft declined from $4.2bn to $2.9bn. Apparently only $700m of the unencumbered aircraft are Section 1110–eligible (acceptable in EETCs).

Of course, AMR’s ability to raise liquidity could change very quickly if the industry environment deteriorates. It is possible that, because of the leadership’s references to "unsustainable" losses and the speculation about Chapter 11, American may already have lost access to the capital markets.

As a last resort, the company might be able to raise funds from the sale of non–core assets, such AMR Investments, though in the current market it would probably not get the best prices for them. Based on one earlier estimate, AMR may have $3–4bn in unencumbered non–aircraft assets.

All of this, and in particular the reduction in financial flexibility, may mean a liquidity crunch for AMR by the next winter season. Much, of course, will depend on the economy and the airline’s ability to restructure its labour contracts.

CFO Campbell provided a sobering reminder of a longer–term problem that American and other large network carriers will have to deal with if they succeed in pulling through the current crisis: high debt levels. At the end of 2002, AMR had $19.3bn of net debt and a net–debt–to–total–capital ratio of 95.8% — its highest–ever leverage ratio (around 70% was the norm for the company for many years).

The need for cost savings

American has so far identified only half of the $4bn annual structural cost savings that it believes it needs in order to survive in a permanently changed revenue environment.

Given the scale of the current losses, the cost cuts must be achieved relatively quickly.

The earlier intention (as presented in AMR’s early November recovery plan) was to "engage labour constructively" to obtain perhaps $1bn of savings mainly through efficiency and productivity improvements.

However, United’s Chapter 11 filing in early December made it both necessary and potentially easier for American to negotiate more substantial labour concessions.

American is now counting on its workers to contribute the bulk of the $2bn required additional cost savings. It has been in "open and blunt" talks with all of its unions since October. In mid–January the company sought to step up the discussions, proposing weekly meetings and offering to open its books to the unions and their financial advisors.

Speaking as one voice under "AMR Labor Coalition", the unions have publicly pledged to help find solutions to the financial crisis. As an indication of the new spirit of cooperation, progress has been made with the pilots on the regional jet scope clause provisions (American’s single biggest competitive disadvantage in the current pilot contract).

However, it will not be possible to reach any agreement on wage concessions or major contract revisions until it is known what happens at United.

Campbell summed up the situation as follows: "No airline will survive without competitive labour costs. But the definition of competitive labour costs has been changing at a blinding speed and is clearly going to continue to evolve. We are extremely mindful of that."

In many ways, American and others are looking to United to use the Chapter 11 process to lower the benchmark at least in respect of pilot pay. This is because in late 2000 United raised the bar considerably for the rest of the industry with its extremely expensive pilot contract.

American is sending a clear message that the sacrifices are shared. To date, it has cut management staff positions by 22%, deferred management pay increases for two years in a row and is consolidating its headquarters operations from 11 buildings to two.

In December the company asked employees to forgo this year’s scheduled wage increases. It is not yet clear if anything could be done about the soaring pension and medical costs, which the leadership described as the most frustrating part of the cost structure. Medical costs are rising by 10–15% year–over–year for active employees and 25% for retired employees.

AMR has refuted suggestions that it could be severely disadvantaged by UAL’s and US Airways' efforts to slash aircraft ownership costs. Campbell argued, first, that the bulk of the cost savings at both UAL and US Airways were expected to come from labour.

Second, most of the lease cost savings were coming from aircraft that were being rejected; in other words, the airlines were shrinking, which was not bad for American.

Campbell also pointed out that the Chapter 11 process itself imposes additional costs, and that American believed that it could achieve labour cost savings outside of bankruptcy.

It is hard to speculate what UAL will look like in the longer term. Anything can happen between now and mid–to–late 1994, which is the earliest that it could emerge from Chapter 11. Of course, if UAL were liquidated, American would be the largest beneficiary.

Changes to the business model?

American’s longer–term plans are based on the premise that, even with economic recovery, the high–yield segment will not recover fully and that the major network carriers will not return to their former profit levels.

The airline intends to meet the market challenges through network and fare structure changes.

Network changes mean moving capacity to more profitable international routes, cutting domestic ASMs, utilising more regional jets and reducing seasonal and daily peaks in the schedule. Many of these changes are already under way.

As regards to fare structure changes, it will basically mean experimentation. As CEO Don Carty remarked in November, "everyone realises that the pricing structure is broken, but no–one knows how to fix it".

One of the basic problems is that the gap between domestic business and leisure fares has grown unacceptably wide. Late last year American became the first major carrier to start testing a simplified, lower fare structure in 25 domestic markets. The experiment reduced walk–up fares by 40% while raising some leisure fares.

Campbell suggested that American has to do more than other network carriers to readjust to the new environment, because its network, product and pricing have all been totally optimised to meet the needs of the traditional business traveller. However, the adjustments will have to be designed so that they will have minimal negative impact on the business segment.

As a hub–and–spoke carrier, American’s costs will always be higher than those of point–to–point low fare carriers. Likewise, American believes that, in the longer term, it can achieve and maintain a 30% unit revenue premium over low–cost competitors — a prediction that is based on 30 years of experience of competing with Southwest.