SAS: its latest reinvention

February 2002

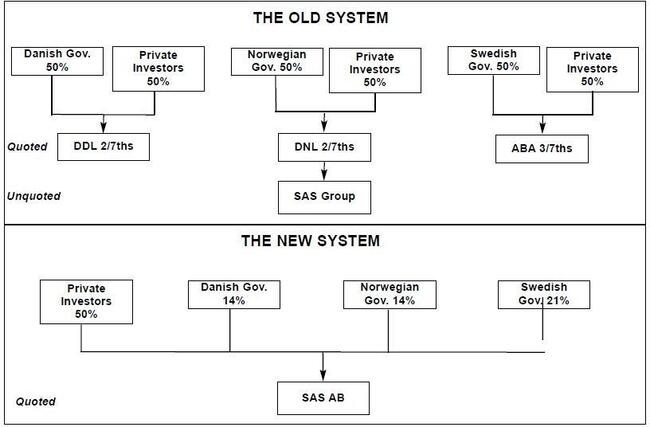

One of the handful of truly multinational carriers, SAS is the pooled consortium of the national airlines of Sweden (government–owned ABA and Wallenberg–controlled SILA), Denmark (DDL) and Norway (DNL).

Established in the 1950s, the national carriers retained the legal entities and route rights of their home nations and operational capacity was derogated to a consortium.

This multinational carrier was created simply because none of the four were large enough to develop and maintain international flights sufficient for the Scandinavian region.

Each of the national stakes in the consortium were 50% held by the respective governments, thus legally ensuring the nationality ownership requirements under relevant bilateral agreements. Under this agreement SAS was required to maintain national involvement within the airline to the proportions of parent company ownership — 2/7ths of the aircraft, personnel etc had to be Danish, 2/7ths Norwegian and 3/7ths Swedish. A secondary consortium, SAS Commuter was established in the 1980s.

SAS’s main operations base is at the Copenhagen hub of Kastrup, with subsidiary bases in Stockholm’s Arlanda and Oslo’s (new) Gardemoen airport. It dominates domestic flights within the extended Scandinavian area, and operates a significant number of intra- European international flights.

Intercontinental exposure is limited — despite being excellently placed to provide long–haul polar connections through Copenhagen, SAS has never persuaded the traveller (who tends not to look at polar map projections) that journey times are shorter by going north in order to go east or west. As a result, only 5% of passengers and 6.5% of revenues come from long–haul operations.

SAS is primarily a business airline, carrying the highest proportion of business traffic among its major European competitors. It was one of the main pioneers of short–haul business class — and undoubtedly will be in the forefront of the next stage of branding development.

Thanks to the regional geography (particularly in Norway) and the requirement to fly commuter legs, SAS has one of the shortest average stage length of any major flag carrier (only 500km). This creates significant difficulties for any analysis of competitive position compared to the other European flag–carriers.

Unavoidably, though, it has a high unit cost base and needs a high yield just to break even.

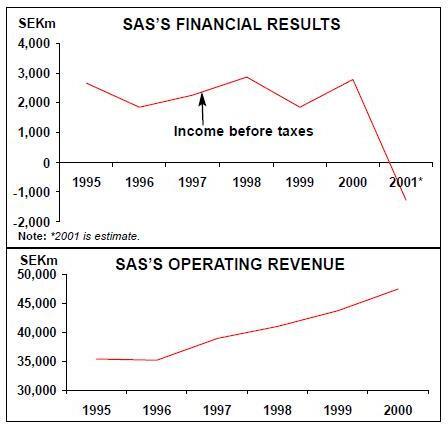

Business cycle decisions

SAS has been remarkably closely linked to the business cycle. In each of the last three cycles it has had to reinvent itself — and ironically for SAS, each cyclical downturn in the industry has come just after a decision to expand. In the early 1980s, under the tutelage of Jan Carlsson, the group restructured, setting up separate business units for its trading, hotel, leisure and other businesses. It took stakes in Continental (before its last Chapter 11 bankruptcy) and Lan Chile in an attempt to develop a global network — a move anticipating industry consolidation by a decade.

At the height of the cycle it managed to get involved with a disastrous acquisition of Intercontinental Hotels. In the 1990s SAS dis–posed of its leisure interests and stakes in Continental, Lan Chile, Intercontinental and Diners Club Nordic. In their place it signed–up with Lufthansa and the Star Alliance, in effect admitting that its role was that of a regional player, albeit a quality–service regional.

Corporate changes

After more than two decades of discussion, 2001 was marked by agreement from the three Governments to consolidate SAS’s capital structure. In June, the company reincorporated under SAS AB, resident in Sweden, with a single share structure. Each of the holding companies' shares were transferred into the new structure.

The capital markets could finally look at the shares as a single quote and single market capitalisation. SAS had been regarded as a "small market capitalisation" stock in the Swedish, Norwegian and Danish markets, and analysts found it hard to present more than one set of data for one of the shares in one of the markets. In its new structure, SAS is seen as a group with a market capitalisation worthy of attention by most major fund managers.

It has a greater level of international investor interest, a positive share re–rating and a lower effective cost of capital. For the first time, the SAS Group’s stock is transparent, shareholder- and market- friendly.

Fleet renewal

The group is in the process of its largest ever fleet re–equipment programme, which will result in a 50% increase in capacity over six years. Current outstanding orders account for a spending requirement of US$1.5bn.

After operating DC–9s and MD–80s on short–haul routes for many years it has ordered New Generation 737s as replacements.

Since 1998 it has taken 53 of the aircraft, gradually disposing of its DC–9s. However, by end of January 2002, it still had 10 DC–9s (all sold and leased back many years ago) and 64 MD–80s.

Last year, SAS surprised the markets by ordering 12 A321s for use in higher density and leisure routes, and 10 A330/A340s (with seven options) to replace its ageing B–767s. Four A340s were delivered in the latter half of last year and it wet leased an A330–200 from affiliate British Midland early last year. These new aircraft will add significantly to long–haul seat capacity — but also to operational efficiency.

If SAS takes the full consignment, long–haul capacity will rise by around 45% overall — resulting from higher seat capacity and better range. SAS rationalised its decision by saying that it currently only maintains a 25% market share of long–haul operations into and out of Scandinavia and has been operating long–haul flights on very high load factors.

Following September 11, SAS has been negotiating for a delivery rate slowdown.

It recently announced a year’s delivery delay on nine A321s and four737s. It is also likely to accelerate the disposal of its remaining DC–9s, 767s and Fokkers.

Although the new equipment has common cockpit configuration, the fleet renewal programme has created the massive logistical problem of retraining — a long–lasting problem.

Consolidation strategy

After the aborted Alcazar merger project (between SAS, Swissair, KLM and Austrian) and failed plans to lead a global carrier system, SAS signed a joint venture agreement with partner Lufthansa for all services between Germany and Scandinavia.

At the same time, it became one of the founder members of the Star Alliance. Having many years ago taken a 40% stake in British Midland, SAS then sold half of its BMI stake to Lufthansa two years ago, and BMI agreed to join the Star Alliance.

Since then, the Star Alliance has had a real opportunity to build a presence at two major European hubs (Heathrow and Frankfurt airports).

It now has the opportunity to challenge British Airways' stranglehold at Heathrow — through the combined power of the slots held by SAS, United, BMI and Lufthansa it can claim a position at LHR similar to the one that American enjoys at Chicago O'Hare against United.

SAS has been busy ensuring that it retains control in Scandinavia. It has control of Air Botnia in Finland to counter the Finnair attack into its home territory; Air Baltic to take feeder control to and from the emerging Baltic States; CimberAir in Denmark to control Danish domestic traffic; Wideroe for services to and from Greenland (still Danish although outside the EU) and finally co–operation between SAS and Skyways has been approved by the Swedish competition authority.

Already in partnership for five years, there has been clarification of code–share and flight schedule adjustments that have satisfied the Swedish authority’s scrutiny and monopoly concerns.

A significant move was the purchase of a majority stake in Spanair in 2001. (SAS helped establish Spanair when it was part of its leisure portfolio). SAS now owns 74% overall, with the possibility that Lufthansa might take a stake à la BMI. Already acting as a partner for several Star Alliance members, Spanair is is likely to become a full member of the alliance in the next few months. Spanair has dropped its longhaul operations, though it has implemented some new code–sharing arrangements with, for example, Aerolineas to Buenos Aires.

In time, this carrier might be able to provide the low cost fill–in service throughout Europe to the Star Alliance (through wet lease or own operation) that is needed.

Finally, last year SAS gained authority approval to take over long–standing competitor Braathens in Norway (previously aligned with KLM). As a result it should now have a near monopoly over Norwegian domestic flights.

This all–devouring consolidation policy has sometimes come at a price. SAS was fined more than €39m (US$34m) for its participation in an illegal anti–competitive pact with Denmark’s Maersk Air in August 2001.

The two carriers had secretly agreed not to compete on key routes between their own countries. SAS’s commercial division chief, Vagn Sorenson, resigned in the wake of the EC’s findings. At Maersk, both the chairman and managing director resigned and the company was fined €13m.

The SAS group now regards itself as having some major competitive advantages.

It enjoys effective control over the Scandinavian region. It considers that it has superior market position in an extended catchment area encompassing the Nordic region and Baltic states of a population exceeding 100m people.

SAS services many routes that other carriers would not be willing to operate (such as Norwegian domestic services) but it also operates on lucrative routes which could come under threat from other carriers.

What SAS appears to lack is a coherent strategy to fight the incursion of low cost operators.

It cannot do it on price. SAS is by definition high cost — as must any carrier operating in Scandinavia. This does not stop the likes of Ryanair attacking some of SAS’s more lucrative short–haul routes (particularly UKScandinavia).

In the near future, SAS will see low–cost airlines operating out of Gothenburg airport. Now that BMI has started up bmibaby as its answer to the bus operators, SAS may be able to persuade Michael Bishop to transfer some operations into its home base — but is likely to encounter significant union pressure at home if it did.

Post September 11

SAS had already been seeing weakness before September 11 in its home markets of Sweden and Denmark and their weakening economies — although Norway was performing reasonably well.

Business traffic — its mainstay — overall was weak.

Traffic plummeted Immediately following the disaster in September, although not as badly as other European carriers. In the three months following the attack on New York, SAS traffic fell by 21% compared with a 31% decline for AEA members. Although there was a mild recovery from these depths in December, business traffic has slumped by 16% since September.

The company has reacted by reducing capacity by some 15–17% and instituted price rises and a surcharge to cover increased security costs. It has renegotiated its aircraft delivery programme, and is accelerating its aircraft disposal plans. The introduction of cost cutting measures will lead to the redundancy of some 2500 employees and further efficiency programmes aim to improve profitability by SEK5.5bn.

Results until August 2001 had already been disappointing and the company issued what was effectively a profit warning. The results for the nine months to end September showed effective break–even and proved to be the worst in its history. September 11 aside, the company suffered a fatal accident at Milan Airport.

SAS revealed that it expected to announce a SEK1.0–1.5bn loss for the year (excluding extra–ordinaries). In the current environment, profitability is unlikely to return in 2002.

However, the group still has SEK17bn in equity, a fleet value significantly in excess of book value and, despite its aircraft acquisition plans a reasonably positive cash flow. Having established financial targets of 17–20% CFROI, 12% ROCE and 14% total shareholder return over the business cycle, SAS has a long way to go before it can prove that it is not destroying shareholder value.

| SAS | Air Botnia | Spanair | |

| 737-600 | 30 | ||

| 737-700 | 6 | ||

| 737-800 | 17 (6) | ||

| 767-300EREM | 12 | 3 | |

| A320 | 3 | ||

| A321 | 3 (9) | 3 | |

| A330 | (4) | ||

| A340 | 4 (3) | ||

| MD80 | 64 | 37 | |

| MD90 | 8 | ||

| DC9 | 10 | ||

| F28 | 4 | ||

| 146-RJ85 | 5 | ||

| TOTAL | 158 (22) | 5 | 46 |

| Sweden | 70% |

| Norway | 37% |

| Denmark | 60% |

| IntraScandinavia | 87% |

| Scandinavia-UK | 46% |

| Scandinavia-Europe | 50% |

| Intercontinental | 25% |