Europe's low-cost carriers - where will it all end?

February 2002

Europe’s low–cost carriers are oozing confidence, reporting strong growth rates, record profits, and placing large aircraft orders, while their traditional rivals languish.

Ryanair has just placed an order for 100 737–800s plus 50 options at the lowest unit price ever ($29.5m, before escalation factors, might not be wild speculation). It now is planning on a fleet of 178 jets and a passenger base of 55m by 2010.

easyJet has yet to decide on the size and composition of its upcoming mega–order, but it will not be eclipsed by Ryanair. Its chief executive, Ray Webster, talks of an eventual 300–unit fleet, and the immense potential for profitable expansion — by taking daily frequencies on London–Edinburgh up from 12 at present to 20 or even 30.

The low–cost carriers continue to push back boundaries and attack markets that were once the sole preserve of the flag–carriers. For instance, easyJet’s advertising now promotes its "Hall of Fame", containing the top European companies that now include easyJet in their business travel policy. Ryanair has signalled a modification in its secondary airport strategy by signing up with Rome Ciampino.

They are, however, still running into barriers as they expand their bases in continental Europe. easyJet has been frustrated by its meagre allocation of slots at Paris Orly where it intends to build a hub. The Iberian peninsula remains blocked off to Ryanair because AENA, the Spanish airports authority, for the present, refuses to allow airports to negotiate special deals. Lufthansa is insisting on taking Ryanair to court under arcane German consumer legislation, though in the process is generating some good local publicity for Ryanair.

Ryanair and easyJet are confident about maintaining at least a 25% pa growth over this decade, while the AEA’s intra–Europe and domestic traffic growth has traditionally plodded along at 4–5% pa.

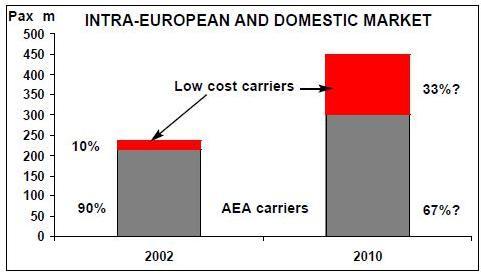

The graph illustrates how these divergent growth trends could change the face of European aviation in the medium term.

Assuming that the low–cost carriers achieve half their growth from stimulating new markets and half from capturing traffic from the incumbents, then their share of the intra European scheduled market will surge from about 10% today to 33% by 2010.

This is noticeably larger stake than the 15–20% of the US domestic market that Southwest and its clones now command (though that share is set to increase substantially in the post–September 11 environment).

There are several reasons why the European low–cost carriers might achieve greater penetration.

- There is a wider unit cost differential between European low–cost carriers and the Euromajors than between Southwest and the US network airlines;

- The European market is much more geared towards point–to–point operations with limited scope for intra–European hubs; and

- The disintegration process for the politically- based European flag–carriers has only just begun.

For the AEA airlines it is not just a question of losing market share to the low–cost carriers. The probability is that the low–cost airlines will divert ever–increasing numbers of the full service carriers' intra–European point to point passengers whose average yield is usually higher than those of short/long haul connecting passengers. This poses a further threat to the viability of their European operations and to their overall network profitability.

BA, in its "Future Size and Shape" strategic review, says that it will face up to the low cost carrier challenge by emulating their mode of operation on its own short haul network.

But because BA is at its core a network carrier with a strong focus of business–orientated long–haul travel, it is difficult to see how it can successfully replicate the key elements of the low–cost model. For example:

- Because of the magnitude of intralining and interlining passengers on its short haul flights, it has to continue to rely on conventional distribution channels and cannot maximise the power of the internet;

- To maintain an overall service image it is obliged to keep frills like free food and FFP schemes on its short–hauls;

- Maximising aircraft utilisation is constrained by the need for connectivity at main hubs;

- Cutting overheads is vital for BA but it cannot get close to the low–costs, whose managers are happy to work in converted hangars.