CRM: the search for airline customer retention

February 2001

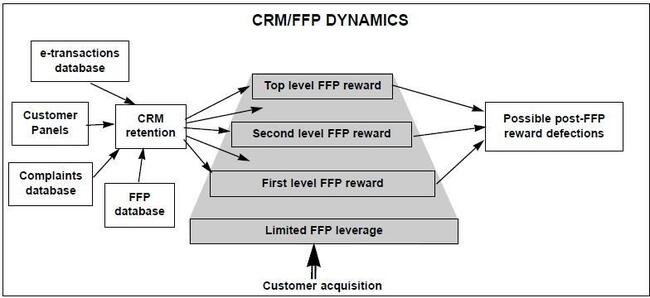

It is roughly five times more expensive to acquire a new customer than to retain one. Customer Relationship Management (CRM) is emerging as a key technique for optimising customer retention, in the process enhancing margins and reducing costs. In the airline sector CRM utilises Frequent Flyer Programme and customer complaint databases as a data sources.

Electronic ticketing and Web–based booking channels will make it even more effective. Airlines have used FFPs since the mid–80s, accumulating in some cases 15 years or more of data on as many as 15–18 million different passenger records, allowing insightful understandings of customer trends and behaviour. But the power of the FFP to ensure the loyalty of a passenger to one specific carrier has eroded as frequent fliers hare often members of multiple schemes (up to 4.3 FFP affiliations/ customer) or have found themselves able to earn transferable points on different airlines within a global alliance. In their original form FFPs were at least partly designed as a way of providing a strong incentive for business passengers in the US to accept lower service quality and the inconvenience of connections over hubs rather than point–to–point flights. Today it is becoming more and more difficult to use FFPs as an alternative to predictable and high quality service experiences. Indeed, with the competitive differentiation advantage provided by FFPs declining and programme management costs rising, it is becoming cheaper to optimise the service experience than to reward customers for accepting something that under–delivers.

The FFP leverage point

The actual travel experience is becoming a more and more important consideration for a growing number of air travellers. Looking at the substantial growth of time–share bizjet market during this upturn in North America and Europe, one can clearly detect a shift off airlines and into a more predictable, easier to control premium business travel experience. Delivering multiple brands in the same airline tube seems to be more difficult than it once was. Despite the shift full–service airlines really cannot afford to let this trend accelerate. They have to enable their premium customers to play a role in shaping their own travel experience, giving them a real or perceived control over the service provided. This is where CRM comes in — the core intent is to proactively build and manage and retain customer relationships in order to create sustainable competitive advantage. The longer and more detailed the FFP data trail, the easier it is to implement effective CRM. Many carriers have such data but relatively few regularly leverage it into effective information that allows them to minimise preventable customer defection.

Some carriers use the data the same way American Express does — identifying substantive defections or reduction in purchasing behaviour, then following up directly with the customer in an attempt to prevent permanent defection. This reactive approach is something that some 15- 20% of airlines have the capability to do but many among those execute the defection recovery process in a sporadic and ineffectual manner. The lack of consistent execution means that the leverage is reduced and of course the returns in terms of retention are diluted.

The second value stream for FFP data is to follow the example of some of the leading retailers, Wal–Mart, Amazon.com, who both apply predictive behaviour–based models to their data.

These models permit the data to be manipulated into an information stream that allows the prediction of individual and customer group activity. The airline can then tailor its value–added services in order to differentiate its brand and mass customise the service experience for the customer.

Today, most traffic forecasts are generated by using the demand modelling capabilities of the Yield Management System (YMS). These systems do, however, still have a critical weakness when it comes to predicting market behaviour at the turns of the economic cycle (such as the peak that is being reached in North America).

The CRM–based model would deal with individuals as opposed to routes or O&D sectors.

Thus, CRM–based approach allows more precise tracking and therefore better predictive capability while also providing the platform on which customised service offerings can be reliably delivered to high value customers.

A practical marketing strategy would involve moving frequent customers to a CRM–premised model while sticking to YMS–based models for the rest. The FFP data stream can provide a strong competitive advantage presuming one can leverage it both reactively and proactively. The key guiding metrics involve driving preventable customer defection to zero while increasing share of wallet for retained customers to 100%.

Aside the FFP–based CRM applications, one must also consider additional methods of leveraging customers to help shape the service process. For instance, Mercedes–Benz and Marriott Hotels and others have used CRMderived ongoing customer research dialogues and customer panels in order to achieve a type of brand–bonding with their customers. This process includes the following elements.

- Customer–aided service process : the idea is to instil a sense of brand affiliation and even ownership by, for example, implementing directly individual passengers' requests and informing them of the airline’s actions.

- Product evangelising: this means encouraging satisfied passengers to share their positive experiences. For this to work the airline has to recruit at least twice as many satisfied passengers as dissatisfied ones, as one positive brand experience typically generates five word–of–mouth contacts while one negative experience generates ten contacts.

The e-CRM future

- Mass marketing service perception: the aim is to persuade as many customers as possible that the airline’s process has been delivered to or built around them specifically. Direct marketing and advertising campaigns along the lines of "You asked for more legroom/bigger overhead bins/fully reclinable beds etc. so we have provided them" attempt to deliver this message. There are numerous benefits and some incremental costs in moving to an e–CRM model, but the potential of this approach has yet to be realised. Nevertheless, the powers of properly executed e–CRM are substantive to the point where the key functions of customer behaviour tracking and defection prevention can be accumulated outside the FFP and YMS infrastructures.

Start by creating an e–sales (passenger or cargo) database that records all transactions between the airline and the customer. Customers can be B2C (individual customers), B2B (sales to corporations) and C2B sales (from third party players like Priceline.com). The trick is then to try and force as many reservations, service and information requests and booking transactions through this system.

The e–CRM database depends for its development on an expansion of the proportion of passengers booking online. This implies that airline has to start regarding internet sales as the core of its distribution strategies rather than as an exotic add–on. Costs savings from cutting agency commissions should ideally be used to fund the development of the airline’s web–enabled booking channel.

FFP–based CRM systems track member activity over time. This tracking only occurs when the actual flight is taken and points (or flight mile) accumulation takes place. An e–CRM–based system would track all interactions (not just completed transactions) with FFP members and non–FFP members. Also, booked but not–travelled transactions would also be recorded.

The addition of these types of transactions to the database will give marketers a much clearer picture of a customer and the total state of their relationship to the firm. For example, how many times customer A booked and travelled versus the number of times he/she booked and no–showed. How many times has a customer used duplicate bookings as a way to protect seats? What is the average value of a specific customer, and what travel patterns does he/she perform over the course of a year. What kind of incentives work best with this customer?

If detectable and repetitive patterns emerge then marketers can consider which personally customised value–added offerings can be provided to ensure retention. Instead of route–based or mass discounting, targeted and precise incentives can be offered to the best customers on a specific route, thus saving the airline money by reducing unnecessary discounting.

Promoting to the key customer group becomes much more focused, therefore reducing the need to indulge in expensive and imprecise mass media–based market communications activities. The age–old debate between airlines and travel retailers as to who owns the customers would be resolved in the airlines' favour.

The power of e–CRM is even more evident in the corporate sales segment. The use of aggregating and powerful query–based software allows airlines to track exactly the performance of corporate customers. Individual passenger activity from the same corporate customer can also be monitored to determine the total value of that firm to the airline. By tagging individual customers the airline can also aggregate the total corporate travel pattern.

Owning loyalty

The key objective of e–CRM is to drive customer (individual and corporate, passenger and cargo) preventable defection rate to zero. This will have the net effect of cutting customer acquisition costs to the bare minimum while reducing communications and channel costs. In terms of the size of the e–CRM database, the ultimate aim should be to get as close as possible to 100% of the browser and user data trails.

Downstream benefits of an e–CRM program could, after a transition period, result in the gradual abandonment of the FFP altogether as, by comparison, it becomes a blunt tool for ensuring customer loyalty. Under e–CRM the airline can establish individual targets for rewarding key passengers as opposed to setting general population thresholds.

Yield management staff would be able to link individual traveller profiles with flight segments and determine where unduly high concentrations of no–shows (by name) seem to agglomerate.

This data could then be used to try to change customer behaviour through incentives or penalties that would over time reduce no–shows and thus the need for overbooking. The value of specific data provided to the yield management staff can eventually allow more effective forecasting, and lead to better allocation of capacity.

Further commercial uses of the e–CRM database would include the researching of new product or service ideas with the appropriate consumers. Also, any high quality database with accurate and real–time information on customers represents significant value for alliances, suppliers and other users of customer data.

In the final analysis, the internet booking part of the CRM approach to customer relationship management allows airlines and other network–based service firms to move from mass–based commercial practices to individual precision targeted methods. This in turn allows the airline to know most of its customers and for the successful practitioners of e–CRM, own their loyalty.