Frontier: survived and prospered against all the odds

February 2001

Against all odds, Frontier, the largest of the early 1990s generation of low–cost airlines in the US, has survived and built a highly profitable hub operation at Denver (DIA) in head–to–head competition with United. To consolidate its success, in May the carrier will begin an ambitious programme of replacing its entire fleet of used 737s with brand new A320s. What will be the impact of the fleet transition, and will Frontier continue to go from strength to strength?

Only a few years ago, Frontier was losing heavily and faced an uncertain future. Like many of its contemporaries, it had a shaky start (in July 1994) because it was very thinly capitalised and initially chose the wrong markets. It tried to stay out of harm’s way by operating on thin routes and feeding to United, but United did not need another feeder at Denver.

A new strategy of focusing on larger markets with low–frequency operation, introduced in late 1995, enabled the carrier to earn marginal profits in the first half of 1996.

It also succeeded in raising $7.3m in a common stock offering and another $2.7m through a private placement, just before the industry sector was hit by the ValuJet crash and grounding.

But Frontier then plunged back to losses as United began its alleged "strong arm" tactics at Denver. In 1997 United also brought the Shuttle to some of the Denver markets, while Western Pacific, another low–cost carrier in search of larger markets, decided to move its operations from Colorado Springs to DIA. A subsequent code–share and merger deal between Frontier and WestPac fell through, and WestPac filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. All of that meant that the Denver market became saturated with excess capacity at deep–discount prices.

The situation improved dramatically in 1998, following WestPac’s shutdown and Washington’s determination to crack down on predatory behaviour by the major carriers. As the DoT had predicted, the mere threat of new rules and serious investigations made carriers like United clean up their act.

Those favourable developments enabled Frontier to secure a $14.2m equity infusion in April 1998, which gave it adequate cash reserves for growth. It grabbed the opportunity to re–establish itself with a sound business plan and gradual growth strategy. In the first place, that meant becoming transcontinental, with services to Boston, Baltimore and New York LaGuardia, and focusing more on the higher–yield business travel market.

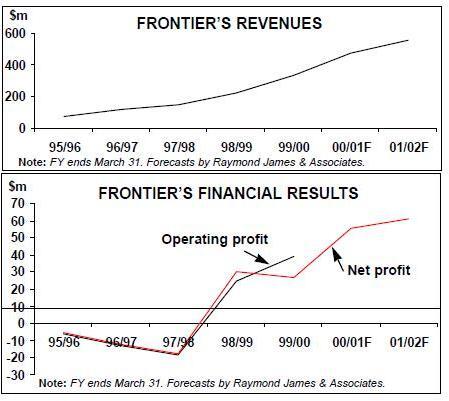

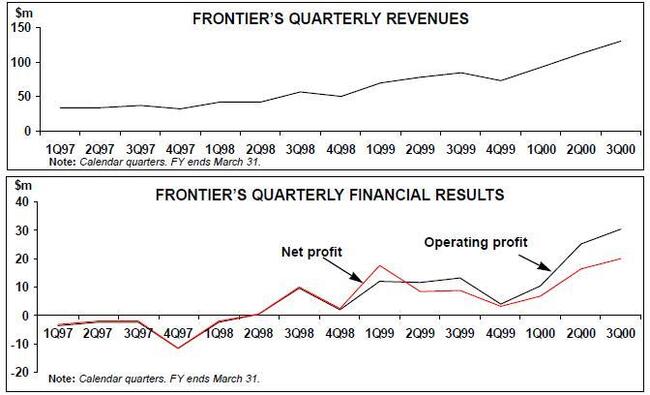

As a result, Frontier staged an impressive financial turnaround, reporting a $24.7m operating profit and a $30.6m net profit for its fiscal year ended March 31, 1999. The net profit represented 14% of revenues. For the previous year the carrier had posted operating and net losses of $18.6m and $17.7m respectively. This was followed by a 59% increase in operating profit to $39.3m and another healthy $27m net profit in 1999/2000. In the two–year period, revenues more than doubled to $329.8m.

Despite last year’s extremely challenging operating environment, which led to a decline in industry earnings, Frontier more than doubled its operating and net profits in the six months ended September 30, 2000.

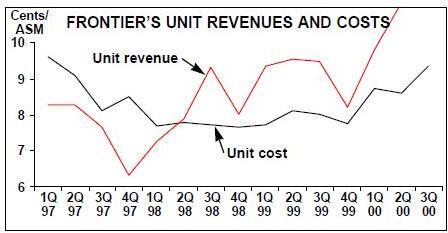

Its operating margin in that period was a stunning 22.9% — the highest in the industry. The past two years have seen exceptionally strong unit revenue growth, as Frontier has expanded to higher–yield markets, improved its product and scheduling, achieved excellent operational performance and captured more corporate accounts. In the September quarter, when revenue per ASM surged by 29% from 9.49 to 12.21 cents, the carrier also benefited from traffic diverted from United because of the major’s operational troubles.

Frontier has also benefited from higher aircraft utilisation and other efficiency improvements as the fleet and DIA hub operations have grown, as well as, of course, lower distribution costs. Bringing ground handling and most maintenance functions back in–house also led to substantial cost savings.

Unit costs have, inevitably, risen considerably due to higher fuel prices, wage increases, increased employee bonuses, higher lease rates on larger and newer 737- 300s and upgrades to internal systems in preparation for the fleet transition. Costs per ASM surged by 16.5%, or by 11.8% excluding fuel, in the September quarter. But there was nothing there that would prompt concern, in light of the general difficult industry conditions and Frontier’s exceptionally robust revenue trend.

The company’s balance sheet is now in good shape. Since prepaying some $3m of notes in late 1998, Frontier is now virtually debt–free. Between March 1998 and September 2000, cash and short term investments rose from $3.6m to $120.9m, total assets from $50.6m to $254.2m and stockholders' equity from a deficit of $5.7m to $120.1m positive.

Co-existence with a Major

The $121m cash reserves, which Frontier described as "adequate", are more than enough to withstand any economic slowdown. The reserves are comparable with slightly–smaller AirTran’s $104m at year–end, which AirTran’s leadership indicated that they felt extremely comfortable with. Frontier is rather unusual among the US low–cost carriers in that it has a hub–and spoke, rather than point–to–point, type of operation, and all the more so because it shares the hub with a major carrier. This obviously has important implications for strategy.

The carrier does not price in the Southwest model, because "we live under the United umbrella". Entering high–fare markets with highly–publicised 60–70% lower fares would be far too provocative. Instead, it uses a stealthier "as you get closer to the departure date, the fare difference will get bigger" approach, as described by its leadership.

Also, Frontier’s fares are nowhere near as low as Southwest’s (it calls itself an "affordable–fare" airline), which enables United to maintain a premium fare structure at DIA.

Even though Frontier is now present in 17 of the top 25 markets out of Denver, its 9% market share at DIA or continued rapid growth there do not threaten United’s 70% market share. This is particularly the case since the bulk of Frontier’s share has come from growth in the Denver market.

DIA seems like an ideal place for this kind of major–new entrant confrontation, because it is a major growth market and has no facility or runway constraints on expansion. Frontier also says that the airport was "built to handle bad weather".

Jim Barker, analyst with Raymond James & Associates, suggests that United’s interests may be served by having a relatively small and rational competitor like Frontier at DIA, because it "weakens the travelling public’s perception of United as a monopolist in the Denver market". Also, Frontier’s presence is likely to deter other more aggressive low–cost competitors.

Fleet transition

In a notable departure from its previous strategy of utilising leased 737–200s and 737–300s, in late 1999 Frontier decided to phase out its then 20–strong Boeing fleet in favour of a new all–Airbus fleet by 2004.

In the first place, the carrier wanted brand new aircraft, which would offer significant cost savings in flight operations and maintenance, as well as financial benefits due to accelerated depreciation and the associated reduction in income taxes.

New aircraft will also better reflect its fresh upmarket image. The carrier recently unveiled a new aircraft livery for the Airbus fleet on a giant IMAX screen at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science "to provide the world with a visual representation of this new era".

The Airbus product was chosen for its "superior economic return, fleet flexibility and commonality features", as well as increased passenger comfort (wider aisles and seats). Availability was also a rather interesting factor. Although Boeing could offer earlier deliveries, the schedule offered by Airbus fitted much better with the general flow of 737 lease expirations.

During the first half of 2000, Frontier finalised its agreement with Airbus, ordering 12 A318s and A319s for delivery between May 2001 and September 2004. It also entered into separate agreements with GECAS to lease 15 new A319s and one A318, with deliveries between June 2001 and October 2004.

On top of the 28 firm commitments, there are 17 options, nine of which have delivery dates assigned (in 2003–2005). Frontier is expected to order another five aircraft, to bring the total deliveries by the end of March 2005 to 50 aircraft. When the replacement programme is complete, the fleet will consist of roughly two–thirds A319s and one–third A318s.

Half of the new aircraft will replace Frontier’s current 737 fleet, which still grew by five aircraft last year to facilitate around 20% capacity growth, and the other half will be for growth. All of next fiscal year’s additions (three purchased and three leased A319s) will be for growth, which is expected to be "in excess of 22%".

Operating leases on the existing 18 737- 300s and seven 737–200s currently expire between April 2002 and May 2006. Frontier says that it may need to extend some leases and negotiate shorter terms or subleases on others, to fine–tune their exits to the Airbus delivery schedule.

There is obviously flexibility in the fleet plan, in terms of aircraft numbers and acquisition methods. Now that the balance sheet has recovered and profit margins are high, Frontier will certainly be looking at purchasing options, including EETCs, traditional bank financing and leveraged leases. As regards to operating leases, the aim is to secure longer leases and more favourable terms generally. Frontier said that it hopes to lease the new and larger aircraft at the same cost that it currently leases its 737s.

The company expects to incur fleet transition costs of around $4.5m annually over the next two fiscal years. Those costs begin in the current quarter and will peak in this year’s June quarter at $1.7m.

Cost savings are expected to build steadily to $2.95m in the March 2003 quarter. Fuel cost savings, assuming a price of $1 per gallon, are estimated to be $27,000 per month per aircraft. Maintenance cost savings are estimated to amount to $50,000 per month per aircraft during an aircraft’s first year of service and $35,000 in the second year. Lower maintenance reserve costs are expected to result in a monthly saving of $35,000 per aircraft.

The savings will be offset by higher landing fees and ownership costs. Monthly rentals and anticipated ownership costs are expected to be $30,000 higher per aircraft. Frontier calculates that it will incur net additional costs of $3m in aggregate in the first three calendar quarters of this year and net savings thereafter. The net savings will accelerate from $690,000 in this year’s December quarter to $2.2m in the March quarter of 2003.

Prospects

As favourable revenue trends have continued, Frontier is expected to report another spectacular rise in earnings for the current fiscal year ending March 31. Jim Parker, one of the few analysts covering the company at present, estimates that earnings per share will surge by 109% to $2.94.

The next fiscal year will bear the brunt of the initial fleet transition costs (mainly pilot training), so Parker expects earnings per share growth to slow to 10%. For FY 2003 he predicts an acceleration in earnings growth to 20–25%, as the cost savings associated with the new Airbus aircraft come into play.

The fleet plan means that Frontier will continue to be one of the fastest growing sizeable US airlines over the next several years.

Frontier should continue to benefit from the rising fares of the major airlines — a trend that is causing business traffic to migrate to lower–fare carriers. The majors look likely to have to raise their fares substantially again in 2001 to counterbalance higher labour costs and fuel expenses (due to lack of hedging). And, as economic growth slows, companies will tighten employees' travel budgets.

A United–US Airways merger and acquisition proposals could lessen the risk of United competing more aggressively with Frontier at DIA for several reasons. First, United will have to watch its act very carefully as it needs DoJ approval for the US Airways deal. Second, the proposed transactions with American reduce the threat of United ending up with excess aircraft that it would move to DIA. Third, since the merger will put pressure on United’s earnings, it can less afford to offer lower fares in the Denver markets.

| Quarter | New fleet | Transition | Net |

| savings | costs | impact | |

| March 01 | 0 | 530 | (530) |

| June 01 | 20 | 1,690 | (1,670) |

| Sep 01 | 450 | 1,210 | (760) |

| Dec 01 | 1,150 | 460 | 690 |

| March 02 | 1,200 | 960 | 240 |

| June 02 | 1,460 | 1,010 | 450 |

| Sep 02 | 1,840 | 1,280 | 560 |

| Dec 02 | 2,320 | 1,100 | 1,220 |

| March 03 | 2,950 | 790 | 2,160 |