The Big Two vision

February 2001

United and American have come up with an innovative plan designed to push through their respective take–overs. But will the plan fly?

To summarise:

- United’s $4.3 acquisition plan for US Airways will continue;

- But United will sell American up to 86 of the US Airways fleet, plus slots at La Guardia and gates at LaGuardia, Washington, and Boston for about $1.2bn;

- American will also enter into a 20–year joint venture with United on the east coast Shuttle with each carrier flying half the daily schedule:

- American Airlines will acquire a 49% stake in DC Air, the proposed Washington–based spin–off from US Airways, for $82m;

- American will purchase all the assets of a liquidated TWA for about $500m.

The America/United proposal was sprung upon a largely unsuspecting world at the same time as George W. Bush was finally confirmed as President. Inevitably this led to speculation that with Bush coming from Texas he would be sympathetic to American and to a $1 approach to big company mergers in general. For the record, American donated about $0.4m to the Bush campaign while United/US Airways donated over $0.5m.

However, these sums have to be seen in context of a total of $430m of funding raised by the Republicans during this election cycle. And early noises from the new Administration indicate that it intends to be tough on antitrust issues. More importantly, there appears to be widespread suspicion of big airlines ion Congress, fuelled by the experience of last summer when limited action of the part of United’s pilots caused widespread disruption in the US domestic market. There is a very effective consumer lobby representing business passengers' interests which is spreading the message that the proposed deal is a monopolistic conspiracy.

If American had merely proposed taking over TWA there could have been no serious objections. Indeed, the US authorities seem set to give full approval for this action. But persuading politicians and regulators that the whole AA/UA/TW/US web should be regarded as a rescue mission is a different matter altogether. US Airways has well–known financial problems but it is not on the edge of bankruptcy and could probably still be turned around. Its third quarter results were so far below expectations that some stock–market analysts consider them to have been artificially depressed.

Network control

American and United appear to have a vision of a Big Two possessing such extensive and comprehensive networks that they would be able to command the loyalty of the premium traveller market in the US and internationally, through the use of FFPs, CRM and direct internet sales.

Competition from the other Majors and the low cost carriers would be still there, but there would be little incentive for the Big Two to compete between themselves. The size advantage that American and United would gain through this arrangement could not easily be challenged by the other Majors because Delta and Continental, for example, could not use the failing carrier argument to justify a merger.

In terms of hubs the AA/UA/TW/US arrangement offers the Big Two a very attractive balance of power. American by taking over TWA would have an important mid–West hub at St Louis to complement Chicago (but with the threat of Southwest inexorably expanding its operation at St Louis). It would also strengthen its position at New York, and split operations with United at Boston and Washington. United would gain a near–monopoly at Philadelphia, US Airways' main hub.

US aviation academic Michael Levine con–tends that the proposed spilt operation of the US Airways Shuttle by American and United encapsulates the Big Two strategy. The Shuttle between Boston, New York and Washington is used primarily by high–yield business passengers who are also frequent business flyers to other cities in the US and abroad. The airline that controls the Shuttle potentially captures a very substantial chunk of the US premium market.

US Airways on its own was unable to realise this potential because of its limited national network (and the fact that the Shuttle did not connect to its Philadelphia hub), but American or United should be able to reap maximum benefit. When American had its marketing alliance with US Airways it gained a relative advantage over United. When United moved to buy out US Airways it threatened to gain a larger advantage over American.

The sharing proposal is therefore a neat compromise. In addition, United and American would be entering into a mutual protection pact against one of the other Majors gaining control of the Shuttle. If, for instance, Delta were to take over the Shuttle and link it in to its network it would easily become the equal of the Big Two.

Delta and Continental will continue to try to sabotage the Big Two strategy, and the most effective way of doing this is by putting in attractive counter–bids for specific assets like the Shuttle and DC Air. Although Continental and Delta are in talks, a counter–merger does not look likely at this point because of regulatory obstacles and the intractable labour problems that Gordon Bethune, Continental’s CEO, foresees.

Labour costs are the other major driver behind American and United’s joint strategy. Like almost all the US Majors, American and United have had stressful relations with their unions, particularly their pilots' union, but the two carriers have adopted a similar approach to tackling their relatively high labour costs. In return for getting the unions to agree to reducing average labour costs (through A/B scales in the case of American and through wage freezes under the ESOP in United’s case) the two carriers initially committed themselves to fairly rapid growth. But this growth has not materialised partly because the other carriers, notably Southwest, themselves expanded and won market share.

Now labour has become the critical issue again. With ESOP–related snap–backs, United is facing a 30% increase in pilot costs, and it can ill afford any more disruption after the pain inflicted by the limited action last year. American has managed to negotiate a one–year extension of its pilot agreement to August 2002, but seniority and payscale conflicts over the TWA take–over rumble under the surface.

This is the dilemma for the Big Two: they know that any merger causes intense and often disastrous labour disruption (even a minor transaction like American’s purchase of Reno), but they can see no other way of reducing average labour costs except through growth. All the indications are that the US economy is finally turning down after its extended expansion, so there may be little intrinsic traffic growth generated, leaving growth through M&A as the only option.

Overall, American and United seemed to have come with a very clever arrangement to promote their mutual interests, but the outlook is becoming murkier, with regulatory, competitive and union complications compounding daily.

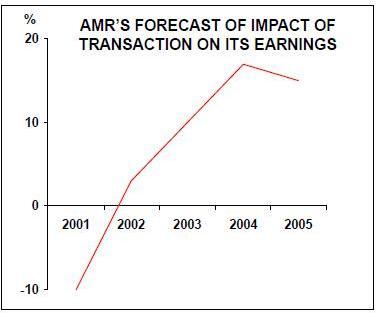

Investment bankers generally love the idea of M&A in the airline industry as they see consolidation leading to an improvement in RoI. Other financial institutions are reading the situation differently. The rating agency, Standard & Poor’s, has stated that it will probably lower American and United’s credit rating if their respective takeovers go through. Julius Maldutis, the most experienced equity analyst of all, has put a sell notice on American, on the basis that all US take–overs have damaged the equity of the purchasing carrier.

| UA/US | Change | AA | Change | |

| from UA | (+TW) | from AA | ||

| today | today | |||

| Mainline jet fleet | 939 | 328 | 991 | 274 |

| Hubs | 6/7 | 2/3 | 5 | 2 |

| Employees | 134,000 | 32,300 | 121,000 | 29,000 |

| Mainline rev. ($ bn) | 25.9 | 6.9 | 22.6 | 5.0 |

| Mainline ASMs (bn) | 228 | 52 | 215 | 53 |