US regionals being swallowed by US majors

February 2000

Delta’s acquisition of its commuter partners Atlantic Southeast (ASA) and Comair, speculation about further mergers and concerns about the renewal and terms of various feeder agreements made 1999 a turbulent, yet still profitable, year for regional airlines in the US.

The biggest of the recent structural changes affecting the regional sector came about as Delta suddenly decided to focus on its feeder operations. The consequence was that, first, in May 1999 it completed the purchase of 72% of ASA, its Atlanta feeder, for $700m (it already held 28%). In October this was followed by a $1.8bn tender offer for Comair, Delta’s 22%-owned partner at Cincinnati and Orlando, and the purchase was completed in January.

Both of these deals were challenged in shareholder lawsuits, alleging inadequate offer price, but amendments to the contract terms enabled litigation to be settled. There were no regulatory obstacles as the competitive impact was considered to be minimal. Both carriers were already heavily dependent on Delta for revenue generation.

ASA and Comair have been retained as separate subsidiaries, with their own workforces and salary and benefits structures. Delta has just formed a new subsidiary, Delta Connection Inc., to oversee their operations, as well as those of four independent regional affiliates.

In terms of feeder integration, this brought Delta somewhere between US Airways Group, which owns three of its ten commuter affiliates but has no specific subsidiary to oversee their operation, and AMR and Continental, which have well–established, fully integrated feeder operations.

This turn of events was somewhat unexpected as many industry observers had predicted mergers between the regionals, following Mesa’s purchase of CCAir. But, instead, it was the majors that drove the deals. AMR purchased Business Express in March 1999 and is now integrating it with American Eagle. This has meant dramatic expansion in New England and southeastern Canada and new hubs at Boston and LaGuardia. Continental recently acquired a 28% stake in privately–held Gulfstream International, its feeder partner in Florida and the Caribbean.

But these deals are obviously much less significant than Delta’s acquisitions, which have meant the disappearance of the two most profitable regional carriers as independent entities. Both Comair and ASA were earning operating margins in the mid–20s, when the range for the next three strongest carriers in 1997–1998 was 10–18%.

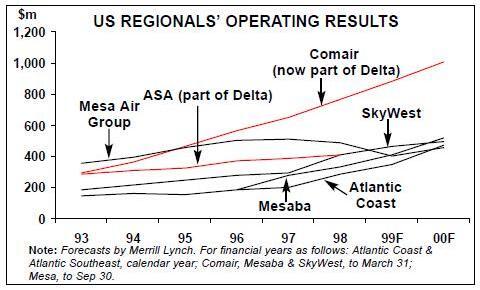

There are now very few sizeable independent regionals left in the US — only SkyWest, Mesaba, Mesa and Atlantic Coast (ACA), plus Great Lakes Aviation (which in 1998 passed the $100,000 annual revenue mark). However, Mesa has lost a total of $137m over the past three years and Great Lakes has also been mostly loss–making. SkyWest, Mesaba and ACA reported an aggregate net profit of $94m for 1998, compared to Comair’s and ASA’s $200m.

Comair dominated the regional sector with an estimated $882m revenues and a net profit of around $143m last year. Its revenues have surged by 15–20% annually since the early 1990s as it pioneered RJ operations in the US. Its success made it a role model for regionals all around the world and fuelled interest in US regional airline stocks, which most analysts only started covering a few years ago.

Rapid, profitable RJ expansion

A reduction in the number of players in a small sector is troubling, even though Comair and ASA had few, if any, direct competitors in the relatively thin feeder markets. The key question now is: will Delta’s moves trigger more regional consolidation? Over the past decade, the regional airline sector in the US has grown rapidly, recording around 10% annual average traffic growth. The initial impetus came when the major carriers started passing unprofitable lower- density short–haul routes to regional feeder partners, which could operate such routes profitably with turboprops and provide a high- frequency service. But the fastest growth rates — as high as 20–30% annually for some carriers — have been experienced over the past few years as the process of utilising regional jets has gathered pace.

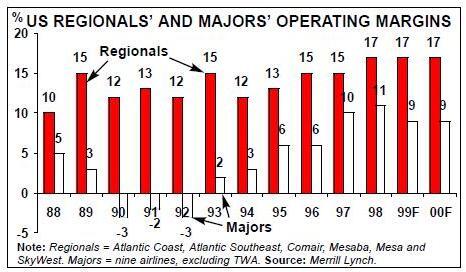

According to Merrill Lynch, since 1989 the six largest regionals have never failed to achieve a combined annual operating margin of at least 12%. Over the past two years the margin has been as high as 17% (significantly influenced by Comair’s and ASA’s stellar performance).

The high levels of profitability attained by the regionals reflect high volumes of business traffic (typically 60–70% of the total), lack of direct competition on the relatively thin routes and low cost levels (lack of unionisation, lower salaries). Some of the companies (Comair being a prime example) have been highly innovative, with excellent managements.

Strong capacity growth has continued (around 24% in 1999 for the six largest regionals) because of the rapid move to utilise the 50–70 seat RJs to enhance the traditional 30–seat turboprop fleets. The first RJ entered service in 1993, and the past three years have seen its system–wide introduction. At the end of 1999 US airlines had around 400 RJs in their fleets, and the number is expected to double over the next three years.

The RJ is fundamentally changing the character of regional operations. Its much longer range has opened up numerous new markets, enhanced the breadth of route networks and reshaped traffic patterns. It enjoys a high level of customer acceptance — a key factor for the major carriers. It has led to significant productivity gains, lower costs and better service standards, while unit revenues have held up fairly well.

In short, the RJs have turned into real moneymakers. One senior Continental executive said recently that the new ERJ–145 services introduced by Continental Express between Houston and various business centres in northern Mexico are among Continental’s most profitable routes (in terms of margins).

However, demand for turboprops is holding as they are often the best choice for the shortest segments (Saab Aircraft Leasing recently estimated the crossover point between turboprops and RJs at 250–300 miles, though the latest hike in fuel prices may have raised it). Among other carriers, ASA recently placed a sizeable new ATR–72 order.

The major–regional consolidation trend is perhaps understandable as the regional jet has blurred the line between the two industry sectors. The larger new–generation RJs will further close the gap. Consequently, the regional jet features prominently in the major carriers' expansion plans.

American Eagle, which has the world’s largest regional jet orderbook (320 orders and options) and a current fleet of about 50 ERJs, has continued its rapid RJ expansion out of Chicago. It has just brought its new 37–seat ERJ–135s to Boston, marking the start of major expansion in the Northeast over the next 18 months.

While Continental Express is currently the fastest–growing regional operation (its traffic surged by 38%) as it expands ERJ–145 service at Houston, United is in the process of aggressively developing regional jet services out of Washington/Dulles, where it is building a hub, as well as Chicago, with the help of ACA and Air Wisconsin.

After building up extensive CRJ operations with Mesa since early 1998, last summer US Airways began adding EMB–145s under a new 10–year agreement with Chautauqua Airlines. This has meant new RJ flying out of LaGuardia,in addition to continued expansion from Washington National. US Airways is known to be very keen to start placing large RJ orders.

TWA — the only major without regional jet service by feeders — is now moving fast to catch up. In November it signed a 10–year agreement with Chautauqua to operate at least 15 EMB–145s at its St. Louis hub from this summer. That was followed by a similar deal covering up to 15 EMB- 145s with Trans States, which will become TWA’s first RJ feeder this month (February). TWA said that the strategy will enable it to "fight back in important and high–value regional markets", where its position has been challenged by competitors' RJ service.

The only question mark hanging over some of the longer–term plans is whether they will be permitted by the majors' pilot unions. Regional jets are a big concern for labour and most pilot contracts include restrictions on jet flying by feeder partners, such as limits on the number of RJs permitted or tying RJ expansion to mainline growth.

US Airways and United have some of the most restrictive union agreements in terms of RJ flying. While the contracts have so far not hampered regional partners' RJ expansion, United is getting close to the limit of 65 50- seat jets agreed on in 1997. This has already delayed new RJ orders that SkyWest and ACA want to place or firm up.

The issue is a key part of the current pilot contract talks at United, and there is obviously hope that the limit will be raised. The two sides have also discussed allowing a much larger number of the smaller RJs (44 seats or less). US Airways’ pilots recently agreed to the resumption of RJ talks.

TWA’s labour contracts previously prohibited RJ flying, but amendments to the pilot contract in 1998 and a new agreement with the mechanics last summer permitted the operation of up to 15 aircraft. The number can rise up to 33 if the mainline fleet grows, and TWA will obviously be talking to its unions about raising that limit.

Continental and Delta appear to be the only majors currently without restrictions on RJ flying. The ASA and Comair acquisitions were permissible under the pilot contract, but all the feeders have to stick to aircraft with 70 seats or less. However, regional jets now feature prominently in the pilot contract talks at Delta that began in September.

Why the ASA and Comair acquisitions?

The union wants to make sure that the regionals will not grow at the expense of mainline operations, so some restrictions seem inevitable. Delta anticipates both acquisitions to lead to revenue gains from more efficient operations, market growth, better aircraft utilisation and improved business functions. But it obviously did not need to buy its feeders for those reasons.

Service quality problems were an issue with ASA, though not with Comair. Delta had raised concerns about some aspects of ASA’s customer service since late 1997 (in part due to labour problems) and had threatened to bring in a new feeder to take over some of ASA’s flying at Atlanta.

The ASA deal, in particular, made business sense in that Delta got it for a bargain price. It made the move before ASA’s share price could benefit from rapid growth facilitated by future RJ deliveries and got away with offering only a 6% premium, which valued the company at just 12.8 times forecast 1999 earnings.

Some analysts think that Delta paid too much for Comair, but others believe that the price was right in light of a possible serious disruption (the contract was due to expire on October 31). Although Delta’s offer price represented a 31% premium, it was below Comair’s 52–week high as the shares had fallen due to concerns about the terms of the new agreement.

ASA and Comair were not typical acquisition targets as they were healthy and extremely profitable. Oddly, it was their extremely high profit margins that led to the loss of independence. Delta had argued that the existing feeder contracts overcompensated the regionals and was pressing for more favourable revenue–sharing.

Delta’s filings to the SEC gave the impression that the major used its muscle to effectively force the small carriers to choose the lesser of two evils. They had to choose between being acquired and accepting new reduced–fee agreements that would have cut their profit margins sharply.

According to the SEC documents, Delta’s proposed new feeder agreement with ASA could have reduced the smaller carrier’s net income by $21m in 1999 and by $45–55m annually thereafter. The terms of Comair’s agreement would have "substantially reduced" its net income, and on top of that Delta had proposed various changes that would have further adversely affected its financial performance.

In ASA’s case, the additional threat to bring in a new feeder and the uncertainty of continuing a relationship that was terminable on 30 days' notice made the outcome inevitable. However, Comair’s board accepted the merger proposal only after seriously exploring strategic alternatives that did not involve Delta.

The deal has certainly paid dividends to ASA in terms of new growth opportunities, which it had previously been denied when Delta was unhappy about its service quality. Over the past six months it has begun numerous new CRJ services out of Atlanta. Its planned LaGuardia- Columbia (SC) service due to start in March marks a new approach in that it will bypass Delta’s main hubs.

ASA’s and Comair’s credit quality has undoubtedly improved, which means reduced costs for financing future RJ fleets. But they are likely to lose some of their efficiency and unit cost advantage, now that they are part of a large company with large overheads. There is also the challenge of keeping the pilot groups separate. All of this means that their operating margins will come down (and we may never know what they are).

Will SkyWest and ACA stay independent?

However, key management talent has been retained, thanks to the appointment of Comair CEO/COO David Siebenburgen as president and CEO of Delta Connection and the promotion of various senior executives within Comair. Delta’s moves understandably led to extensive speculation about possible merger deals involving the remaining independents. Many believed that United, in particular, would acquire either SkyWest or ACA as a defensive move. However, so far there has been no sign of any such response from United. This may have something to do with United’s current contract talks with its pilots. Also, United may have little incentive to acquire SkyWest or ACA as the feeder contracts are working well and do not generate excessively high profit margins for the smaller carriers.

Instead, there seems to be a new trend for a larger number of multiple connection agreements — something that Comair considered before deciding that it had simply built too heavily on the Delta relationship and that it would be too risky to start from scratch with the other majors. This new trend offers hope for the survival of the remaining regionals as independent companies.

As a watershed development, in September Delta forged a 10–year partnership with ACA for the exclusive use of 45 RJs in the Northeast, starting this March. The deal covers 25 Dornier 328JETs (a new order) and 20 CRJ–145s that ACA already had on order for delivery by the end of 2002, plus access to 30 options. ACA set up a business unit for Delta Connection, to separate it from United Express flying.

Like SkyWest, which feeds to Delta at Salt Lake City and United along the West coast, ACA will be a dual–role feeder. It has continued to expand United Express flying at Chicago and Washington Dulles as more CRJs are delivered, while waiting for final approval from United to firm up a conditional order for up to 110 328/428JETs placed in July.

The new Delta contract should be highly beneficial for ACA as it will not only mean new growth opportunities but also diversify ACA’s revenue stream and provide useful leverage with United.

In December SkyWest, too, received a welcome confirmation of the status of its relationship with Delta. Its agreement was extended till June 2010 and it was able to place a long–awaited new order for 20 CRJs for the Salt Lake City operation. Including previous orders, it will take delivery of 55 new CRJs over the next four years. But it is still waiting to hear from United about future RJ requirements on the West coast.

The multiple–partner strategy was pioneered in the early 1990s by Mesa, which continues to feed to US Airways and America West (it lost its United Express contracts two years ago) and independently in New Mexico and Colorado. And the practice is well–established among the smaller regionals like Trans States and Chautauqua.

Mesa appears to have regained the confidence of its partners, thanks to vastly improved operational performance. The US Airways contract was recently expanded to 28 RJs and extended till 2007, and the America West agreement is also likely to be expanded. In late January Mesa placed a long–awaited order for 36 ERJ- 145s plus 64 options, with deliveries beginning later this quarter.

The Delta–United marketing relationship may have eased things for the larger regionals, though analysts say that the major carriers generally now seem more tolerant of sharing their feeders.

Impact of fee-per-departure agreements

However, further acquisitions or mergers obviously cannot be ruled out. The Northwest- Mesaba relationship is rather intriguing in that the small carrier, which continues to perform well financially and operationally and has adequate cash reserves, seems totally dependent on Northwest, which owns about 40% of its stock. But there have been many clashes in the past, and Mesaba now needs to sort out its growth plans beyond June, when it receives its last AVRO regional jet. Might Northwest now acquire it while its share price is still weak, to ensure common goals in the future? The traditional revenue–sharing arrangements between the majors and their feeders have increasingly given way to "fee- per–departure" type remuneration. ACA’s new contract with Delta is on that basis, as are SkyWest’s agreement with United, Mesa’s with America West and US Airways (RJs only) and Mesaba’s with Northwest. This trend has had major impact on the economics of those carriers' operations.

Under the old prorate agreements, the regionals kept all their local revenues and shared the revenues from connecting passengers with the majors. Under the new arrangements, the majors pay a flat fee per flight — in other words, buy the capacity from the regional. There is usually a nominal "incentive payment" per passenger if specific operational performance and service standards are exceeded. The basic payment assumes a specified level of fuel prices; if the prices rise, the regionals are credited the difference.

The new types of arrangements mean that the regionals make the same amount of money regardless of what the fares are and how many passengers are on board. This is obviously beneficial in an industry downturn or a weak fare environment. The contracts also make the regionals effectively hedged against sudden hikes in fuel prices — one of the reasons why Mesaba and SkyWest have continued to post strong earnings growth in recent quarters.

ASA and Comair turned down these new types of contracts, but analysts say that they were probably the only two regionals that stood to lose out and that just about everyone else will benefit. The new contracts will make extremely high profit margins a thing of the past, but they will remove risk and ensure a stable and predictable earnings stream.

Prospects

For Mesa, SkyWest and soon also ACA, the new types of contracts provide a useful way of diversifying risk. Mesa, which reported a satisfactory $7.8m net profit for the December quarter, said that the adverse effects of the Y2K revenue impact and higher fuel prices were “significantly muted” due to the fee–per–departure agreements. By contrast, ACA posted a 23% decline in net earnings as it took the full brunt of the adverse revenue and fuel cost trends. But ACA is expected to reduce its dependence on the prorate agreement with United from 100% at present to 68% by 2002, when 32% of its capacity will be under the "ASM–buy" Delta agreement. A continued rapid rate of regional jet deliveries will maintain the US regionals' capacity growth similar to the past two years' plus–or–minus 20% level in 2000, and good growth is expected until at least 2003.

After that the RJ market may become saturated, given airport and ATC capacity constraints. But there will still be growth as larger RJs are used to develop new medium and long haul markets and boost capacity in markets now served with 50–seat jets.

Earnings growth for the regional airline group should be in the 10%-20% range annually over the next 3–4 years, but profit margins will come down. Merrill Lynch suggests that the long term sustainable operating margin could be around 15%. This assumes continued healthy earnings growth for carriers like SkyWest, Mesaba and ACA and a strong turnaround at Mesa this year.

| Regional | Major | Basis of | % of |

| remuneration | total ASMs | ||

| SkyWest | United | fee-per-dept | 60% |

| Atlantic Coast | Delta | prorated | 40% |

| United | prorated | 68% by 2002 | |

| Mesaba | Delta | fee-per-dept | 32% by 2002 |

| Northwest | fee-per-dept | 100% | |

| Mesa | America West | fee-per-dept | 46% |

| US Airways (RJs) | fee-per-dept | 46% | |

| US Airways (turboprops) prorated | 54% | ||

| Others | prorated | 54% | |