Aircraft lessors - raising the stakes

February 1999

The rules of the operating lessor business are currently being re–written. As with virtually every other facet of the aviation industry, consolidation is likely to be the key feature. In this Briefing Aviation Strategy takes a close look at the aircraft leasing industry and what the future may hold.

Background

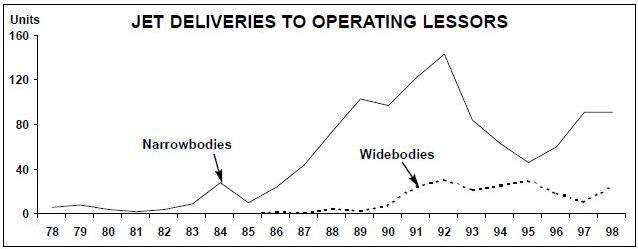

In the 1980s the major lessors consisted of GPA, ILFC and AWAS. The aircraft manufacturers, after significant internal debate, agreed that operating lessors had an important role to play in the industry and that their existence was not harmful to their own bottom line. Yet while the manufacturers were happy to see another form of financing emerge (which would lessen some of their own balance sheet exposure), they also put in place some unwritten rules on the amount of new aircraft they would sell to the lessors. By the mid–1980s a steady but small number of aircraft were being delivered to the lessors (see graph, below), but the lessors’ market share of the total fleet was under 7%.

This system worked well in the 1980s, but the Gulf War and industry recession brought about a fundamental change to the $1. In 1992, GPA reported a pre–tax profit of $279m, but then undertook a doomed IPO which would have valued the company at $3.5bn. The failure of the IPO was the catalyst for a fundamental change in the operating lease industry over the remainder of the decade.

The more speculative lessors made two mistakes. First, they argued that there was a “capital shortage” in the aviation business, based on the difference between the projected number of aircraft required by the world’s airlines and the traditional finance or internal funds available to fund the purchase of those aircraft — and that operating lessors would fill that gap. In fact the apparent capital shortage soon disappeared with a slump in traffic and aircraft demand. This resulted in cancellation of orders and, ultimately, a major improvement in airline profitability.

Second, an extraordinary amount of faith was put in the resilience of residual values. It was claimed that investing in aircraft not only produced a very high rate of return but also the risks (in terms of the volatility of future prices) were almost as low as with government bonds.

Anyway, those myths were exposed with the GPA flotation failure. However, the banking community had noted the high margins (compared to “vanilla” lending to airlines to support asset sales) that could be earned by aircraft lessors — if managed correctly — and they increasingly sought a share of this market.

At the same time, there was a flow of managerial talent out of GPA and the other established lessors. These managers had ambitious plans to establish their own aircraft leasing businesses, and so in the mid- 1990s a number of new lessors have emerged to challenge the old order. The timing was good: the manufacturers were desperate to make sales, and they quickly broke their self–imposed limits on the amount of aircraft they would sell to the lessors in order to avoid a backlog of white–tails.

The keys to success

Success in aircraft leasing depends on the following factors:

- Buying power, which obtains discounts from the manufacturers, favourable slot positions and flexibility to change the aircraft models on order;

- Low cost sources of funding, preferably with access to friendly tax jurisdictions;

- Risk minimisation, through a broad global spread of customers;

- Investment in aircraft types that remain in demand and retain value; and

- Strong management skills in areas such as relationship–building with airlines and banks, re–marketing skills and market awareness (for instance, in anticipating repossession situations).

One measurement of success, apart from survival, is that a lessor is financially robust enough and well managed for Airbus or Boeing to sell it new equipment. Those lessors that have seen out the decade and who fall into this category are listed in the table above.

The top four players

ILFC and GECAS between them account for 57% of the jets owned by the 11 lessors listed. Perhaps more importantly, these two lessors account for well over 70% of the backlog of all jets ordered by lessors. ILFC has grown organically to be the world’s largest lessor, while GECAS took advantage of the distressed position that GPA found itself in after the IPO failure by acquiring its best assets to add to its own existing portfolio.

Although these companies have different management styles, they both share the essential characteristic for success — a low cost of capital plus backing and support from a strong parent. ILFC’s owner–managers, the Udvar–Hazys, sold their company to the US insurance and financial services giant AIG in the early 1990s and have benefited from its AAA credit rating since then. GECAS’s parent, General Electric, has a similar rating.

Through their existing orders, the status and ranking of the top two in the leasing industry is unquestioned. What is very unclear, however, is whether and when a serious rival will emerge to challenge ILFC and GECAS.

The residual GPA is now known as AerFi. It has been left with a substantial portfolio of assets, placing the company third in terms of size in the lessor rankings. But, the AerFi portfolio has a higher than average aircraft age, and some 14% of the fleet in the portfolio complies only with Chapter 2 noise regulations. Nevertheless, AerFi’s special skill lies in managing a client list that carries a lower credit quality level than the customers of ILFC or GECAS, and achieving higher rewards with higher risks.

The exit of GECAS as a shareholder and the entry of David Bonderman’s company, the Texas Pacific Group, may bring some stability to the company although some observers see Bonderman’s investment as a short–term opportunistic gamble. Even if Bonderman does prove to be a long–term player, it is questionable whether even his skills and resources will be enough to keep AerFi in its number three slot in the medium–term.

AWAS is also more likely than not to slip down the rankings. Joint ownership between the TNT Post Group and News Corporation has in recent times not been a positive feature for AWAS. The company is regarded by some as lacking direction and is a potential acquisition target.

The ambitious challengers

Interestingly, the following three lessors, Boullioun/SALE, debis and GATX/ Flightlease have all declared their interest in becoming the world’s third largest lessor behind ILFC and GECAS. It is just such unbridled ambition that will drive the consolidation of this business.

Two of these three lessors have components that belong to airlines. Flightlease is the aircraft leasing subsidiary of Swissair and SALE performs the same role for Singapore Airlines. GATX/Flightlease probably has the weakest credentials of the three to attain eventually the number three slot. While GATX Corp. is a NYSE listed company with a market capitalisation of some $2bn, and Swissair is the twelfth largest airline in the world, the resources behind these two companies is still no match for those behind debis and Boullioun/SALE.

Boullioun was acquired by Deutsche Bank for $120m in 1998 and Boullioun has a 35.5% interest in SALE, which some believe will, in time, be bought out by the German bank on behalf of Boullioun. Deutsche Bank is serious about wanting to grow Boullioun aggressively, and it certainly has the resources. In November 1998, Deutsche Bank announced its acquisition of Bankers Trust in a $10.1bn deal that creates the world’s largest financial institution (with assets in excess of $800bn).

Debis also possesses a parent with both great ambitions in aircraft leasing and the resources to fund such ambitions — DaimlerChrysler AG. The German–American vehicle manufacturer has created a financial services division with a $81bn portfolio of assets, which is only outranked by GECAS, and the financing divisions of Ford and General Motors.

The remaining four

The remaining four lessors in our table are tiny in comparison with the larger players and their future lies probably in carving out their own niche or possibly as being acquisition targets for the larger companies listed above. Survival as a niche player is certainly a possibility. As the big get bigger, complaints are growing that that they are losing touch with the airlines’ needs.

Pembroke, which recently merged with Rolls–Royce’s leasing arm, Aircraft Financing and Trading, may focus on the expanding niche of the business that concentrates on aeroengines. Indigo is a NASDAQ quoted lessor based in Sweden that received its listing in 1998. Sunrock and Tombo are owned by two Japanese trading houses, the Nissho Iwai Corporation and Mitsui.

Although only lessors that have new aircraft on order have been included in this analysis, there are many other lessors dealing in used jet aircraft such as the CIT Group, Pegasus and CLPK that may fall prey to acquisitions.

The future

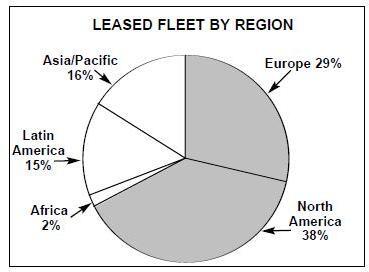

Today the lessors have a market share of around 20% of the world fleet compared with just 7% 15 years ago. The operating lessors’ market share of the jet orderbook is around 18%, but is much higher for the more popular types such as the next generation 737 models and the A320 family. By far the largest penetration of the lessors has been into the North American market where just under 40% of the lessors’ aircraft are now placed.

The use of the operating lease has spread far beyond the traditional market of second–tier airlines with weak balance sheets: the leading lessors have placed up to 30% of their fleets with North American or European Majors. By contrast, the main lessors have only 6–7% of their fleets placed with the Asian Majors at present.

Asia is a growth opportunity for the lessors. The currency collapses have left airlines in the region with hugely increased debt burdens in US dollars; sale and leaseback of aircraft is the obvious means of raising dollar funds. Fleets and network plans are being radically revised; many aircraft are likely to be sold or leased out in order to accommodate changed market circumstances. There is an urgent requirement for airlines to downsize or “rightsize” their aircraft types to match capacity to the new level of demand. As there is still a shortage of some types of equipment in the West, the lessors may have a unique opportunity to benefit from this global imbalance.

There are other growth opportunities in Europe, notably with the state–aided flag carriers that are in various stages of turnaround programmes. Now unable to access state funds, their fleet replacement strategies and network adjustments (which typically involve downsizing from, for example, A300s to 737s or A320s) require them increasingly to use aircraft lessors.

Operating leases are now also being used by the world’s leading airlines as an integral part of their fleet strategies. In deregulated markets predicting traffic volumes becomes more and more problematic, increasing the risk of exposing airlines to overcapacity in a downturn. A key concept for fleet planners is a core fleet supplemented by a flexible fleet that can be expanded or contracted rapidly in response to market conditions; it is the role of lessors to supply the flexible fleet.

However, the potential for extending operating leasing to the leading airlines should not be exaggerated. The leading airlines can still achieve better financial terms from financial institutions and they can negotiate extremely competitive unit prices and terms from the manufacturers.

Which of the lessors will emerge from the post consolidation phase? Unless General Electric sells off or floats GECAS, the existing size of their respective orderbooks means that ILFC and GECAS will remain unchallenged in the near future as the two largest aircraft lessors. The depth of the pockets behind debis and Boullioun suggests that these two lessors will be highly aggressive and acquisitive in pursuing dominance over one another. Consolidation in the medium–sized bracket of lessors is likely to result in one or both of these companies joining the ranks of the mega–lessors, ILFC and GECAS, in the near future.

| Jets | % | Average | % | No. of | No. | |

| under legal | age | wide- | ||||

| ownership Stage 3 | (Years) | body | operators | parked | ||

| ILFC | 397 | 99% | 4.5 | 28% | 117 | 3 |

| GECAS | 317 | 82% | 11.5 | 25% | 98 | 23 |

| AerFi | 236 | 86% | 10.8 | 18% | 76 | 3 |

| AWAS | 110 | 99% | 7.3 | 16% | 52 | 2 |

| GATX/Flightlease | 63 | 97% | 6.3 | 25% | 19 | 2 |

| Boullioun | 46 | 78% | 6.8 | 4% | 19 | 0 |

| debis | 31 | 100% | 4.0 | 13% | 12 | 0 |

| Indigo | 26 | 77% | 9.7 | 0% | 19 | 2 |

| Sunrock | 16 | 100% | 5.0 | 13% | 16 | 0 |

| SALE | 12 | 100% | 3.6 | 50% | 12 | 0 |

| Tombo | 8 | 75% | 11.0 | 13% | 8 | 0 |

| Pembroke | 7 | 100% | 6.2 | 0% | 5 | 1 |

| Cost of 737-800 | $35,000,000 |

|---|---|

| Source of funds for aircraft purchase | |

| Lessor equity | $4,000,000 |

| Debt (via bank loan) | $31,000,000 |

| Source of cash for lessor | |

| Security deposit (3 month’s lease payments) | $1,050,000 |

| Initial 4 year lease @ $350,000 per month | $16,800,000 |

| 2 year extension @ $330,000 per month | $7,920,000 |

| 2 year extension @ $340,000 per month | $8,160,000 |

| 2 year extension @ $300,000 per month | $7,200,000 |

| Total | $41,130,000 |

| Cost of bank debt repayment (7 years @ 7.5%) | -$40,300,000 |

| Net cash earned by lessor | $830,000 |

| Estimated residual value of aircraft | $28,000,000 |

| Total return | $28,830,000 |