American: the right time to resume growth?

February 1999

American Airlines is poised to start growing again this year after a long period of stagnation. But how will it be affected by the continued Asian crisis, overcapacity and fresh economic uncertainty in Latin America and growing labour cost pressures?

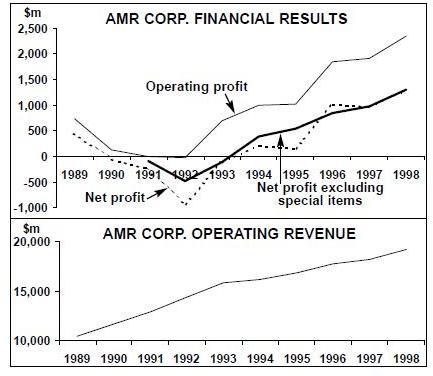

American is probably the most consistently profitable of the large US Majors (excluding Southwest). Except for a marginal operating loss in 1992, AMR Corp. reported positive operating results through the early 1990s recession. Although net losses added up to $1.3bn in 1990–93, much of that was due to restructuring and other special items.

This was quite an achievement in the light of the disastrous 1992 “Value Pricing” strategy, lack of labour concessions, a five–day flight attendants’ strike in 1993 and a long drawn–out dispute with the pilots that led to a “one–minute” strike in February 1997 in which president Clinton intervened.

But American was quick to adopt strategies to help it remain competitive. It improved fleet utilisation, focused expansion on the more profitable international routes and boosted frequencies in key domestic business markets. Instead of launching its own low–cost airline venture, it decided to strengthen its main hubs at Dallas Fort Worth, Chicago O’Hare and Miami, and eliminate secondary hubs like San Juan and Raleigh/Durham. It also implemented a cost–cutting programme that meant streamlining administrative functions, early retirement programmes, some lay–offs and elimination of loss–making routes.

These strategies facilitated strong and steady profit growth, though in 1994–96 the reported results were skewed by huge restructuring charges or special gains. The latest annual net earnings, $985m for 1997 and $1.3bn for 1998 — which included only minor special items — represented 5.4% and 6.8% profit margins respectively.

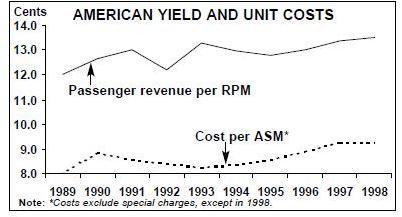

Much of the profit growth has been due to load factor improvements. Between 1993 and 1998 the passenger load factor leapt from 60.4% to 70.2%. In the same period yield crept up by just 1.6%, while unit costs surged from 8.25 to 9.25 cents per ASM — the second–highest after US Airways among the major carriers.

The earnings growth has been achieved against zero overall capacity growth. Last year American produced 3.5% fewer ASMs than in 1993. Over the past two years, capacity has crept up by just 0.7% and 0.9% respectively. American’s management was determined to maintain a strategy of minimal growth even after the signing of the new five–year contract with APA in the spring of 1997, because the deal did not offer any cost savings (it gave the pilots pay increases and stock options).

But the pilot deal was a watershed development in that it made it possible to start planning for the future. American immediately finalised an earlier $6.5bn Boeing aircraft order to kick–start fleet renewal and facilitate future international expansion. It also began to repair its image — the biggest (ongoing) project has been spending $400m to refurbish cabin interiors and provide new seats in all classes in virtually all of its fleet.

Over the past few years AMR has used its free cash flow to strengthen its balance sheet substantially. When raising the company’s credit rating to investment grade level in August 1998, Moody’s said that AMR had one of the lowest leverage ratios, adjusted for off–balance sheet liabilities, among the US major carriers.

Since 1997 AMR has also been returning cash to shareholders — after completing the initial two $500m stock repurchase programmes by the end of September 1998, a third buyback programme of the same size was authorised in October. In June 1998 the company also completed a two–for–one stock split in the form of a stock dividend.

In September 1998 a decision was taken to sell the three AMR Global Services companies — AMR Services, AMR Combs (fixed–base operations) and TeleService Resources — in order to focus on the core airline and related technology businesses. Those three units earned $451m revenues and $40m profits in 1997. All found buyers in December 1998, which will mean special gains recorded in the current quarter.

This was one of the first major strategic moves by Donald J. Carty, who succeeded Robert Crandall as AMR’s chairman/CEO when Crandall retired in May last year. The takeover was smooth as Carty had worked closely with Crandall as AMR’s president since March 1995. Nevertheless, it brought to an end an era as Crandall had occupied the top post since 1985, was a larger–than–life personality and was credited for inventing concepts such as FFPs, hub–and- spoke systems and deep–discount fares.

Carty’s reign has so far been characterised by a more relaxed, informal style, putting greater emphasis on improving labour relations — probably exactly what American needs at this point. He has also stressed the importance of expanding the airline and developing partnerships and joint ventures.

Resumption of growth

After years of stagnation, American is now ready to start growing again — a process that will be facilitated by a surge in aircraft deliveries this year. However, in November the carrier scaled down its growth plans in response to a worsening global economic outlook. It will retire 10 more aircraft (DC–10–10s and 727s) in 1999 than the six envisaged earlier, which will save $40m over three years in maintenance and modifications costs, and defer some international services. The move reduced this year’s planned capacity growth from 6% to 3–4% (10% internationally and 2.5% domestically).

Altogether 45 new Boeing aircraft are scheduled for delivery in 1999, and the fleet is due to grow from 648 at the end of 1998 to 677 at the end of this year. But, like many other carriers, American says that its “flexible” fleet plan will allow it to retire larger numbers of older aircraft if necessary, rather than operate excess capacity.

The 1996 103–aircraft Boeing order, which established a 20–year special relationship with the manufacturer, and subsequent re–orders have added up to a current firm order total for 34 777–200ERs, due in 1999–2001, four and five 767–300ERs and 757–200s respectively, all due in 1999, and 100 737–800s, due in 1999- 2004.

The long–range 777–200s, the first of which was due to arrive in January, will facilitate the retirement of the DC–10 fleet, increase capacity in key international markets and, significantly, allow non–stop operation on US–Asia routes of up to 8,000 miles. The MD–11 fleet is being phased out and sold to FedEx over the next five years. The 737–800s will allow the retirement of the 727–200 fleet by 2004 and provide for “modest growth”.

Domestic strategic moves

Despite the fact that Northwest and Continental have begun domestic code–sharing (in early January), the American–US Airways alliance, like the United–Delta combine, is now not likely to go beyond marketing and FFP cooperation. The two linked their FFPs and club facilities in the summer but appear to have forgotten about domestic code–sharing. Neither liked the idea — or the thought of approaching their pilot unions — much in the first place. The combination of Delta’s pilots refusing to even consider code–sharing and the realisation that Washington would probably frown on the larger- scale link–ups may have killed off the idea.

That said, the mere linking up of their FFPs is likely to produce substantial revenue benefits. American, whose AAdvantage programme is one of the most powerful FFPs in the world, now has access to US Airways’ captive high–yield customer base in key East coast business markets.

Also, in recent months American has found new expansion and acquisition opportunities in the domestic marketplace. First, it is in the process of acquiring its FFP partner, low–cost carrier Reno Air for $124m with the intention of eventually integrating Reno into its operations. The small carrier was worried about long–term survival, while the deal will help American strengthen its position on the West coast.

Second, in early December American and its regional affiliate American Eagle forged a marketing partnership with Alaska and its subsidiary Horizon, which hitherto had been firmly in the Northwest–Continental camp. At first it looked like Alaska had ditched its long–time partner Northwest, but since then they too have expanded their cooperation.

In the third strategic move, in December 1998 Eagle announced that it had agreed to buy commuter carrier Business Express from a Philadelphia–based investment partnership. This will strengthen AMR’s position in the Northeast, which American must be monitoring very closely because of Southwest’s planned expansion to New York and United’s intention to boost its Washington Dulles operations. American has just introduced a daily Boston–New York (JFK) service and in January 1999 it announced plans to build a new $1bn terminal at JFK.

American Eagle has steadily expanded its regional jet operations and load factors have been high. It ordered the 50–seat Embraer ERJ- 145 in 1997, after American’s pilots agreed that their lower–paid counterparts from the commuter affiliate could fly the regional jet. Eagle has so far ordered 50 ERJ–145s, of which about 20 have been delivered, and the first of 25 ordered 70–seat Canadair CRJ 700s will start arriving in 2001. Eagle will reach the APA–stipulated limit of 67 jets with 45 or more seats at the end of 2001, but beyond that the fleet plan is apparently flexible enough to permit growth. Eagle also recently ordered 75 37–seat ERJ- 135s, which will start arriving in July.

International challenges

The fall in AMR’s fourth–quarter earnings was blamed largely on weaker yields in international markets. While the Asian crisis has put a damper on Pacific expansion, Latin American markets have seen overcapacity and lower yields and face uncertain economic prospects. Transatlantic yields have also weakened, while alliance plans are delayed by regulators.

How will American tackle these challenges? After seven years of ambitious expansion, American rationalised its transatlantic network in the mid–1990s and has since then actually contracted a little in Europe, losing its position as the second–largest US carrier to United (Delta is the largest). Transatlantic operating profits rose steadily to $219m or 11% of revenues in 1997, but evidently declined last year due to weaker yields.

Economic uncertainty will constrain growth in the short–term. This year’s planned new services from Chicago to Amsterdam and Moscow have been deferred, but American is going ahead with Los Angeles–Paris and JFKFrankfurt services this summer if it can get the slots. It is also bidding for Chicago–Rome rights under the expanded US carrier service provisions of the new US–Italy ASA.

One major frustration has been the delay in securing government approval for the transatlantic code–share and marketing alliance with British Airways, which was announced way back in June 1996. When the latest round of official US–UK bilateral talks broke down in October, the US government delayed “indefinitely” a hearing on the antitrust immunity application.

While American and BA still hope for eventual government approval, in the short–term they are now pursuing alliance activities that do not require third–party approvals or antitrust immunity. Even before the latest regulatory setbacks, the airlines were talking about phasing in the alliance over 4–5 years, because the EU’s conditions were increasingly seen as commercially unacceptable in the light of a possible slowing of demand growth.

Last year American began code–sharing with Iberia on US–Spain and beyond–Madrid and intra–US routes and with Air Liberte on beyond–Paris sectors. It also expanded its longstanding code–share relationship with British Midland and will begin code–sharing with Finnair this year. American and British Airways are in the process of buying a joint 10% stake in Iberia.

Otherwise, the Iberia and Finnair relationships will be developed in the context of the global oneworld alliance, which was unveiled in September 1998 and also includes Canadian, Cathay Pacific, Qantas and effectively JAL (the latter has forged extensive code–share deals with both American and BA).

Oneworld must be the ideal choice for American since it will give it access to the world’s most lucrative business markets — Heathrow, Hong Kong and Tokyo, to complement its own high–yield markets out of New York and Chicago. Securing the Asian partners was especially valuable, as many of them had been courted by other alliances and because of American’s desire to expand in Asia.

In 1997 American had a minute 4% share of the US carriers’ total Pacific ASMs, and its Pacific routes accounted for just 2% of its total passenger revenues. It is now determined to become a bigger player with the help of new services facilitated by last year’s US–Japan ASA, the introduction of the long–range 777 this spring and code–sharing relationships with Asian carriers.

To complement existing alliances with SIA, Qantas and China Airlines, last year American began code–sharing with Asiana and China Eastern and plans to start code–sharing with JAL and Air Pacific this year.

In mid–January American and JAL outlined an ambitious four–phase expansion plan, to be implemented in May–November this year, to code–share on 76 international and 41 domestic routes in both countries. This will counter the recently–implemented United–ANA code–share alliance and help retain presence in recession hit transpacific and intra–Asia markets.

The new US–Japan ASA enabled American to start serving Tokyo from Chicago, Seattle and San Jose last May, to supplement the successful Dallas–Tokyo flights it has operated since 1987. In December 1998 it also launched a daily non–stop Dallas–Osaka service, its fifth route to Japan, hoping to attract good volumes of connecting traffic not just to eastern US cities but to Brazil and Peru.

In November American decided to defer its planned Boston–Tokyo and JFK–Tokyo services “due to lack of slots at Narita”, though weaker demand or concern about overcapacity due to competitors’ new services may have played a part. As the Asian economic situation is showing little improvement, American must be monitoring the situation very closely.

American’s alliance strategy actually started in Latin America when, about four years ago, it found further growth hampered by regulators’ concerns about its dominance in that region. Since late 1995 it has signed code–share deals with BWIA, ALM, the TACA Group, Avianca, Bolivia’s Aerosur, Brazil’s TAM, LanChile and Venezuela’s Aeropostal, as well as buying an equity stake in Aerolineas Argentinas.

But progress has not been easy. The BWIA and ALM applications were withdrawn due to strong opposition on market domination grounds. The TACA deal, which was instrumental in securing a US–Central America open skies ASA, took more than two years to gain government authorisation — it was finally approved in May 1998 and code–sharing began the following month. The application for antitrust immunity with LanChile is still pending.

On the positive side, the TAM application went through relatively painlessly (code–sharing began in July) because of similar alliance applications from competitors, and on January 26 1999 American announced further code–sharing with TAM. And American and Aeropostal, who announced a marketing and code–share alliance in December, said that they had already secured all necessary government approvals (Delta already code–shares with Aeropostal).

The TACA and LanChile alliances, in particular, hold much promise. American will benefit from TACA’s success and important position in Central America — the original deal envisaged code–sharing on 275 weekly US–Central America flights. LanChile, in turn, dominates many South American markets.

The purchase of a 10% stake in Interinvest closed in November, giving AMR 8.5% of Aerolineas and 9% of regional carrier Austral. While two former American executives had been installed to run Aerolineas, American will not have direct management control or board representation. The code–share arrangement was made contingent on Argentina signing an open skies ASA with the US — now very likely as in mid–January the presidents of the two countries instructed their negotiators to conclude such an agreement by the end of March 1999.

A rare opportunity for American to expand its own South American services came in June 1998, when a new US–Peru open skies ASA — the first such accord to take effect in South America — made extra frequencies immediately available and American was the only airline ready to expand service. It was able to begin a second daily Miami–Lima service in July.

But many of the US–Latin America markets have experienced problems since the early summer of 1998, in large part because open skies ASAs have led to significant capacity additions and lower fares. American’s unit revenues in the region fell by 10% in the June quarter. The situation then apparently stabilised thanks to industry–wide service cuts (American terminated its New York–Lima route on November 1), but the fourth quarter of 1998 evidently saw another 10% yield decline and flat load factors.

Fresh worries about the region emerged in mid–January following Brazil’s currency devaluation, which caused a sharp fall in AMR’s share price. As the worst scenario, Brazil’s economic problems could lead to a deep recession in Latin America. Although American is not any more exposed to Brazil than other US carriers, it dominates the overall US–Latin America market, accounting for about 52% of US carriers’ total capacity. In the first half of 1998, the Latin American division accounted for about 17% of American’s total passenger revenues and 11% of its operating profits.

If the Latin American situation deteriorates, American, like its competitors, would probably reduce frequencies or temporarily halt service in affected markets. Profit margins would probably also decline further. In 1997 American earned a $309m operating profit in Latin America (12% of revenue), but in the first half of 1998 profits were already running at 33% below the previous year’s.

Prospects

Like most of its competitors, AMR reported a decline in net earnings for the fourth quarter, from $208m to $182m, and profits may also fall slightly in 1999. That said, American’s strong balance sheet, operating performance and market position make it relatively well positioned to weather an economic slowdown. Longer–term prospects seem even rosy as the full benefits of oneworld, many of the other alliances, the Aerolineas investment and the US–Japan ASA will take time to materialise.

However, Latin America poses both immediate and longer–term challenges. Overcapacity and demand weakness may necessitate service cutbacks and lead to more aircraft retirements this year, while in the long–term open skies ASAs will increase competition and maintain pressure on yields.

American also faces substantial labour cost pressures. Its pilot costs will remain high for several years, until new contracts take effect at other carriers. The new leadership’s conciliatory style may help avoid acrimony with the famously–militant flight attendants, whose contract became amendable on November 1, but sizeable pay increases are inevitable.

However, the company has worked hard to keep other costs in line, and a combination of cost–containment initiatives and capacity growth may lead to a reduction in unit costs this year.

| Current fleet |

Orders (options) |

Delivery/retirement schedule | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 727-200 | 78 | 0 | To be retired by 2004 |

| 737-800 | 0 | 100 (400) | Delivery in 1999-2004 |

| 757-200 | 96 | 5 (38) | Delivery in 1999 |

| 767-200 | 8 | 0 | |

| 767-200ER | 22 | 0 | |

| 767-300ER | 45 | 4 | Delivery in 1999 |

| 777-200ER | 0 | 34 (38) | Delivery in 1999-2001 |

| DC-10-10 | 13 | 0 | 9 to be retired in 1999 |

| DC-10-30 | 5 | 0 | |

| MD-11 | 11 | 0 | To be retired by 2004 |

| MD-80 | 260 | 0 | |

| A300 | 35 | 0 | |

| F-100 | 75 | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 648 | 143 (476) |