Quality of jet orders, not quantity, is key indicator

February 1999

Aviation Strategy concludes its analysis of jet orders in 1998 (see January 1999 issue) by taking a closer look at the big two manufacturers — Boeing and Airbus. As usual, both Boeing and Airbus managed to unveil some last–minute orders (many previously “unannounced”) as 1998 came to a close in order to bump up year end figures. But what was surprising was the scale of these last–gasp orders: Airbus unveiled an impressive 47 in December, but Boeing trumped them by announcing a staggering 128 orders in the last month of 1998, 64 of them on December 31st alone!

A cynical observer might say that these orders were just part of the ongoing market share war between Boeing and Airbus (see Aviation Strategy, September 1998), and not all of them may be as firm as they seem. Nevertheless, the net effect was to bump Airbus’s total orders for 1998 to 556 and Boeing’s to 656.

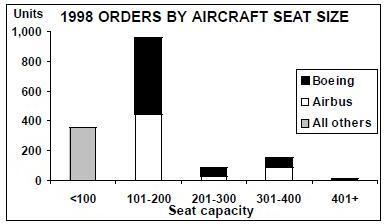

In terms of orders by aircraft seat size, the 101–200 seat category accounted for 61% of all jet orders in 1998 (see graph, below), with the 737 family outselling the A320 family by 516 aircraft to 437. In the other categories, Boeing maintained its grip on 201–300 seats (the 767 and MD–11 outgunning the A300), while Airbus won the 301–400 seat battle (A330 and A340 versus the 777). Interestingly, in the top category — 401+ seats, where Boeing has a monopoly (for the moment) — there were just 14 orders for the 747.

A pyrrhic victory?

However, although Boeing kept ahead of Airbus in terms of orders last year (and in deliveries, by 563 aircraft to Airbus’s 229), by most other criteria Boeing had a dreadful 1998. The past months have been dominated by the decline of Boeing’s share price, following the manufacturer’s profit warning for 1999 (a 25% reduction on previous estimates) and the forecast that in the year 2000 aircraft operating margins will be in the range 1–3% (compared with 10% earlier this decade).

In addition, Boeing announced a downward revision of production rates across its entire range of aircraft. For example, the 747 — which has been a cash cow for Boeing in recent times — will face a reduction in production from 3.5/month to just 1/month in early 2000. Consequently, Boeing stated that it is to cut 20,000 jobs over and above the 24,000 job losses previously announced, a total 20% reduction in the workforce.

Boeing placed blame for the bad news squarely on the Asian crisis. Some carriers have cancelled orders, while others have asked Boeing for a deferment of their deliveries beyond 2000.

Quantity versus quality

The fall–out from the Asian (and now possibly South American) crisis will be key to the big two manufacturers’ fortunes in the the immediate future. And that’s because some aircraft orders are more “firm” than others (i.e. those from Asia and South America, which are much more likely to be cancelled or deferred).

The table (right) shows the difference between Boeing and Airbus in respect of their exposures to the Asia/Pacific and South American markets.

Boeing has clearly outsold Airbus in Asia, particularly at the long–haul end of the market, and this exposure (or perhaps overexposure) is now the cause of many of Boeing’s problems. With over half of the backlog for 747 aircraft and 40% of 777 orders in Asia, any further deterioration of this market would be even more painful for Boeing. As airlines downsize their networks and enter global alliance structures this may put further pressure on these airlines to review their long–haul orderbook.

With the benefit of hindsight it is easy to criticise Boeing for carrying too much exposure in Asia. But until the crisis broke, nearly all forecasters predicted Asia would continue to be the primary engine of global traffic growth and therefore Boeing’s fight to keep Airbus out of the market was justified.

Nevertheless it is the practice of banks, operating lessors and other practitioners in the aviation industry to try and limit their exposure to individual airlines or markets and to try and spread risk. If one criticism is justified it is that Boeing has not been successful at spreading its risk.

So if Boeing has problems, has Airbus escaped entirely? Airbus’s exposure in Asia is more evenly spread between its long–haul and short–haul products, and arguably the orderbook is of a slightly higher quality than that of Boeing. For example, the primary orders for the A340 are with Singapore Airlines (eight aircraft) and with All Nippon (five aircraft), carriers that are among the most robust in the region.

While Boeing has fought an aggressive sales campaign in Asia, Airbus has fought hard to break into South America. Most notable of Airbus’s successes in South America last year were orders for a total of 57 A319s and 33 A320s from LanChile, TACA International and TAM of Brazil. However, Boeing is fighting back and on January 19th 1999 it surprised Airbus by securing the sale of eight 737–700s to Panama’s COPA.

Yet Airbus has a backlog nearly four times larger than Boeing’s in the continent. Some forecasters predict that South America is another Asia crisis waiting to happen, particularly given the recent crash in Brazil. But even if this does happen, the Airbus exposure is far more limited than Boeing’s in Asia, and importantly the Airbus backlog is almost entirely A320 family aircraft, which arguably are more easily re–marketed than long–haul aircraft.

The Asian crisis and Boeing’s woes raise some important issues.

- As the Asia/Pacific market has been the mainstay of the 747 programme in recent years, if the fall–off in traffic proves to be a permanent feature, the question arises how many markets remain that have the right characteristics to support the 747?

- If Asian markets follow the transatlantic trend in downsizing from 747s to the big twins, then does a market really exist for either the 747–X or the A3XX?

- If Airbus officials believe that the Asian markets will recover, does Airbus take advantage of Boeing’s latest predicament and launch the A3XX? Can it afford to take such a gamble both financially and with impending market flotation?

- One of the industry mantras has been that the next recession will be less severe than previous recessions as a result of the manufacturers being able more easily to match demand to supply than ever before. The troubles that Boeing has experienced in firstly cranking up production and now turning off the tap seem to provide evidence against this assumption.

| Asia/Pacific | South America | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft backlog |

% of total backlog |

Aircraft backlog |

% of total backlog |

||

| Boeing | |||||

| 737 | 104 | 10% | 17 | 2% | |

| 747 | 56 | 52% | 0 | 0% | |

| 757 | 6 | 5% | 1 | 1% | |

| 767 | 13 | 10% | 8 | 6% | |

| 777 | 103 | 40% | 6 | 2% | |

| Total | 282 | 17% | 32 | 2% | |

| Airbus | |||||

| A300/A310 | 5 | 10% | 0 | 0% | |

| A320 family | 70 | 7% | 105 | 11% | |

| A330 | 23 | 14% | 3 | 2% | |

| A340 | 10 | 9% | 0 | 0% | |

| Total | 108 | 8% | 108 | 8% | |