The CorpExpress challenge.

February 1998

A key trend in the aviation industry is the way in which first and business class markets are beginning to change in ways that most had not predicted. Louis Gialloreto looks at the lessons that can be learnt from changes that are occurring in the US market.

Many people will remember the much vaunted threat to business air travel posed by the fax, express delivery services, teleconferencing, the web and the like (the so–called telco/tech systems). According to forecasts made three or four years ago from business lobby groups and think–tanks, it was predicted that between 8–15% of business air travel volumes would be deflected away by these technologies. But as some analysts now realise, the predicted haemorrhage due to these specific factors has not transpired at the anticipated pace.

Of course there are factors that tend to reduce business travel, such as the current Asian economic debacle or improving short haul rail infrastructure in Europe, but the predicted 15% downturn in business air travel does not appear to have happened. In fact, one could argue that globalisation of business together with increased joint venture/ M&A activity has produced a stimuli to an otherwise lethargic market.

A new threat

However, just before airline strategists settle comfortably back into their chairs they should take note of several other phenomena that are posing the threat of change to first and business air travel markets.

The end of 1997 saw the creation of a US–based airline called Access Air, which is funded directly by a several US corporations, including Caterpillar Corporation and Pioneer Hi–Bred International (the world’s largest seed company). The initial strategy of the airline bears a striking resemblance to that given at the launch of now established carrier Midwest Express. That airline was funded heavily by Kimberly Clark, otherwise known as the Kleenex company — thus giving rise to "the Kleenex airline". Based at the then underutilised Milwaukee airport, Midwest Express has grown to the point where it now operates 26 DC9/MD80 type aircraft in a consistent single class 2x2 configuration — in what is the equivalent to a US domestic first class service standard.

It seems that Access Air may follow a similar strategy, in particular through offering better value to customers (i.e. better service at business class fares that are as much as 60- 65% less than what the majors offer). Could this be the start of something new in generic corporate involvement in passenger air travel? Might one eventually see Air GM, Air P&G, Air Unilever and the like? One could speculate that Ford’s mini–fleet of BAC–1–11s at Cologne, or Air Fiat at Turin and the like, could form the basis for one of several Eurobased CorpExpress–type carriers.

In fact, the benefits of a CorpExpress airline can be substantial, especially since these niche–based carriers tend not to be driven by unduly strong growth intentions, are conservatively operated, place a premium on community involvement and development, and can usually dominate their main base (mini hub) operation, bypassing the major hubs with point–to–point service.

Given the fact that these airlines usually carry employees of their corporate parents for free — and residual asset values cover any major risk — the overall net result for the corporate parent can be free air travel, break–even or even better for the airline, and all of the intangible community benefits that come from fostering local economic development.

One might ask what series of circumstances led to the formation of Midwest Express and now Access Air — and can these circumstances be repeated elsewhere? Lack of interest by major airlines that are concentrated in and out of their major hub points is one reason. A second is the reduction of point–to–point air services that strong hub based networks imply — thus forcing the Milwaukee–located businesses of this world to fly via somewhere else. Thirdly, the fact that the majors have been unable to deliver a consistently memorable service experience because of their size, far flung operations etc, has also helped create the market gaps that these small CorpExpress niche players can maximise. The result is lower fares that are near impossible for the majors to match for any protracted period of time.

Timeshare jets

There has also been a relative explosion of corporate quarter/half ownership and timeshare business jet programs, to which more and more business jet assets are being pledged. In fact, all the major manufacturers either have their own or have partnered with some of the larger Jetnet–clone type organisations that exist. One might suspect that the business jet market is cannibalising itself by allowing corporations or individuals to rent or own pieces of aircraft.

Instead, the volume of direct sale business jet transactions does not seem to have suffered all that much, if at all.

Therefore, one must presume market stimulation — but from where are these "new" customers corning? As more and more small and medium sized companies see that they too can own/rent a piece of a business jet, and that this is more cost effective and flexible than relying on airlines, there will be an impact on first and business class cabins at the majors.

Already larger corporations can now have a 1.5 or 2.5 net jet capacity to cover their travel needs, using a combination of wholly–owned and part owned/rented jets — and the quarter/half ownership scheme is encouraging many other medium and smaller corporations to get into the game.

Timeshare ownership can also offer substantial tax benefits.

When one combines the net effect of the two aforementioned phenomena, plus: the impact of the Asian downturn; telco–tech systems (fax, web, teleconference etc); stronger short haul multi–modal competition in some areas; and the smaller size of middle and upper management travel markets in this cycle versus the last, then one has to wonder what airlines can do to preserve first and business class volumes.

Super business class, better hub–link and some point–to–point services with regional jets are some responses. Simultaneously, airlines have seen fit to try and reduce the unwieldy burden of distribution channel costs by capping commissions. But while from the airlines' perspective the attempt to reduce distribution costs is long overdue, the negative consequence from the corporate travellers' perspective is that they are now directly paying for travel agency services — and this on top of quickly inflating air fares. If this effect is filtering through in a period of economic upturn, except for Asia, then what of the recessionary phase of the cycle?

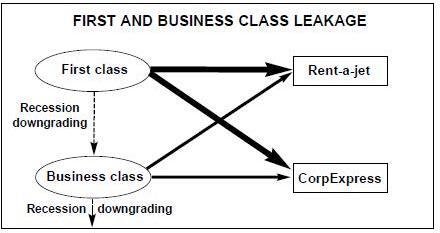

Indeed, to state the obvious, business travel is cyclically impacted and many of the higher fare paying passengers slide back to the next level during downturn (first to business, and business to economy). Therefore when the next downturn happens, first and business cabins will feel the effects of two trends — cyclical downgrading and a continuing switch to timeshare jet programmes and CorpExpress airlines (see diagram, below).

The message to strategists is clear — first and business class leakage is increasing. Although the effects of recession and telco/tech systems have been anticipated, the effects of CorpExpress airlines and timeshare jets have not been. Airlines therefore have a long way to go before they can truly claim to have solved first and business leakage.