Italian airlines: the Alitalia family and others

February 1998

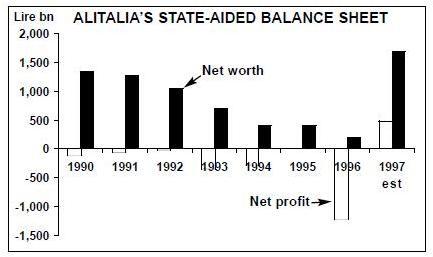

Alitalia is claiming a serious turnaround following the injection of L2.75tr ($1.1bn) in state aid — estimated net profit for 1997 could be L500bn ($275m). While this is a welcome contrast to the rest of the lira–draining 1990s, the recent sale of Alitalia’s 30% stake in Malev will have contributed significantly to the result. IRI, the state holding company, has floated the idea that the remaining L750bn in state aid be raised through a public sale of part of IRI’s 86% holding in the flag carrier. In return the EU would be asked to relax the conditions imposed on the state aid (for instance, allowing the airline to expand capacity more quickly than the overall market rate).

Alitalia’s confidence that it will be able to part–privatise this year (a sale of more than 49% of the carrier is currently illegal under Italian law) is based on some initial successes in curtailing costs, the development of the Malpensa hub and its alliance with KLM (see page 1) — but perhaps its most important asset is its continuing dominance of its domestic market.

With about 18m passengers a year, the Italian domestic market is slightly larger than the UK’s and comparable with Germany’s. More than 80% of passengers travel on Alitalia or one of its associates. Only two full service airlines (Air One and Alpi Eagles) go against Alitalia on trunk routes, and both of them are doing badly. The start–up carriers are now mostly beholden to or at the mercy of Alitalia. While their strategies may have been naïve, probably the biggest challenge they have had to face is the influence Alitalia has with the government, from slot allocation to traffic data. Nevertheless, effective local competition to Alitalia may materialise if the northern charter airlines are able to build up their scheduled operations and if another Euro–major takes a stake in and redirects the main domestic competitor, Air One.

Alitalia's subsidiaries

Alitalia Team was created in 1996 in order to absorb the former domestic operator Avianova and create a low–cost subsidiary. Team crews are paid less than in the core airline and they can also be based outside Rome (mainly at Milan).

The plan is to transfer all Alitalia employees to Alitalia Team by the year 2000, at which point the name will presumably revert to Alitalia. The Team brand is not emphasised: the name appears in small letters below the Alitalia logo, and the only way for a passenger to differentiate between the subsidiary and the parent is that service tends to be better on Team flights.

Alitalia Express was spun off from Alitalia Team apparently because there were major problems merging pilots' seniority lists. Alitalia Express has taken over the ATR fleet, but its future may depend on how Minerva develops as an Alitalia feeder.

Alitalia also owns a charter company, Eurofly, which has now even been given a scheduled route, Bergamo–Rome. Alitalia is committed to supporting this operation now that its stake in Air Europe has been sold.

Alitalia's associates/code-sharers

Minerva is a bit of a mystery airline, rumoured to be financed by Alitalia. It earns 50–60% of its revenues by operating Alitalia flights, is losing money and has swallowed a third of its capital in a year of existence. In 1998 it expects to carry 400,000 passengers, 70% of whom will be provided by Alitalia. It has five DO328s, and a sixth is delivery, probably wearing Alitalia colours.

Azzurra Air, set up by ex–Alitalia executives with 49% equity ownership from Air Malta, had a difficult beginning, but has now been able to close a deal with Alitalia. It still operates a few flights out of Bergamo and Turin, but two aircraft have been placed in Milan Linate, operating for Alitalia to London City, Valencia, Munich, Geneva and Frankfurt. More destinations will be added in summer 1998, when the fleet will rise to seven, from four BAe 146s at present. This will give Alitalia some relief from its EC–imposed fleet constraints.

Azzurra had initially made a deal with Swissair to operate code–shared flights to Zurich from Turin and Venice. The Turin services are operational but the three planned dailies from Venice have been jeopardised by the agreement with Alitalia. Azzurra also recently signed a code–sharing deal with Debonair for services between Bergamo and London Luton.

Air Malta had planned to sell its stake, but the Alitalia deal may have made the future of Azzurra more interesting for the original investors. In 1998 it could be formally integrated into the Alitalia Group.

Alpi Eagles, based at Venice and Verona, is said to have lost $20m since it started flying in June 1996, and has had a turbulent management history as well as being plagued with reliability problems among its six F100s. The latest chairman and MD recently resigned, to be replaced by Sig. Rusconi, the founder of Minerva and previous head of Air Dolomiti.

The airline has never really decided what it wants to be: at first it attacked Alitalia head–on on the Venice–Rome route with a ticket–less, low–fare, full–service, two–class operation; then it started code–sharing with Alitalia in the winter of 1996/97; then in the winter of 1997/98 it reverted to independent operation, this time with traditional tickets.

However, it had also been negotiating a deal to become a feeder for Alitalia at the new Malpensa hub starting in the next summer season, but these talks have stopped.

Meridiana, Italy’s second biggest carrier, is under pressure. Its costs are at least as high as Alitalia’s. In 1996 management copied Alitalia’s strategy by setting up a lower cost subsidiary, Meridiana Express, to which all its routes were to have been transferred. However, this appears to have been little more than a cosmetic exercise, and now its only response appears to be downsizing: its international network is being quietly dismantled.

Somehow Meridiana has managed to keep Alitalia and Air One out of its Olbia niche (Sardinia). And, for the first time in its long history, it started code–sharing with Alitalia on its nonstop North–South routes. At least these defensive measures have enabled the carrier to break even again, but its longer–term future is uncertain.

Air Sicilia, based at Palermo, has three years of experience flying three ATR42s, during which time it claims to have broken even. A code–share deal with Alitalia on routes between Sicily and some smaller islands collapsed the day before service was due to begin.

Med Airlines, set up by former Air Sicilia staff, operates exactly the same routes and aircraft and has been able to gain Air Sicilia’s Parma–Rome route, one of those small–city–to the- capital routes for which lots of cash is available from local government. In effect, both carriers are competing to become Alitalia feeders.

Med seems to be better capitalised than Air Sicilia. Two Saab 2000s will soon be delivered. Italair is another ATR42 operation set up in August 1997 by a group of former Alitalia employees. The plan is to expand the fleet to five aircraft, develop feed to Rome and Milan and eventually international service. It badly wants to become part of the extended Alitalia family.

The Italian independents

Air Dolomiti, a pioneer of regional service in Italy, started operations in 1991 from its base at Trieste. It has had some major positioning problems, but thanks to its major shareholder — the Leali group, an important steel producer, which owns 75% of the stock — it has had the money to survive and now the investment is paying off.

It has now ended its agreements with Crossair and Air Engiadina, and is focusing on feeding Lufthansa at Munich and growing its new focus cities, Verona and Genoa. Of its 24 flights a day (one–way), 15 end up at Munich, and all of them, including those to Barcelona and Paris, carry the LH code. It can claim to be Europe’s first regional airline to set up a hubbing operation outside its own country.

Air Dolomiti states that it carried 360,000 passengers in 1997 and that revenues reached L110bn ($60m). It will add four ATR72s and one more ATR42 in the early part of this year, and will later finalise plans for regional jet operations. Having built up a great reputation for its service, it has been able to resist pressure from Lufthansa to operate in Team Lufthansa livery. It recently completed a successful capital increase, which saw new shareholders — mostly financial institutions from the Trieste region — take 25% of the company. But direct ownership from Lufthansa at some point in the future cannot be ruled out. Air Europe, based at Malpensa with seven 767s, finally got rid of its unwanted shareholder last year when it bought back the 24.6% owned by Alitalia. This removed the barriers to it becoming a scheduled carrier, a role which Alitalia had previously blocked.

December 18th 1997 was a historic day for Italian aviation: the first ever intercontinental scheduled flight not operated by Alitalia left Milan bound for Havana (although most of the seats were still sold to tour operators). In Italian aeropolitical terms it was a breakthrough; Spain, for instance, has three long–haul scheduled carriers.

Moreover, in early January Air Europe started scheduled service to Mauritius after the Italian government stripped Alitalia of the rights.

On the other hand, Air Europe could not go through with its IPO, originally planned for December 1997, mainly because of general stock–market uncertainty. Although it has developed a passenger base of about 0.8m passengers a year and achieved revenues of L361bn ($200m) in 1996, it depends on operations to countries like Cuba, Dominican Republic, the Maldives and Kenya, which do not appear to offer a suitable base on which to build a scheduled network. If there is going to be any vertical integration between tour operators and charter carriers in Italy, Air Europe will probably be the right target for a take–over.

Lauda-air Italia, also based at Malpensa, is one–third controlled by the Austrian Lauda–air, and is meant to be the initial step for the Viennabased career to conquer a much bigger market than its own. Initial results were break–even at best but in 1997 it increased revenues by 40% to L100bn ($55m) and achieved L6bn in profit.

It will operate two 767s this winter and plans to add one more. It has applied for scheduled service on 25 long–haul routes not operated by Alitalia, and very aggressively threatens major legal action should the Italian government not award them. Lauda–air won a case in court against Alitalia regarding scheduled rights to Santo Domingo, even though at the moment Alitalia is still flying the route.

This is all very reminiscent of Lauda–air’s emergence as a serious competitor to Austrian ten years ago. Still very small, but with a quality reputation, Lauda–air Italia may yet pose a threat to Alitalia’s development of the Malpensa hub.

Air One was the first airline to seriously confront Alitalia in the domestic market, particularly Milan–Rome, having been founded by a group of ex–Alitalia employees and backed by the Toto civil engineering conglomerate. But it lost more than $10m on revenues of $70m in its first full year of operation, 1996; local reports suggest that 1997 revenues will double, but so will its losses.

Air One is usually referred to as a low–cost carrier, but the main reason its labour costs are below Alitalia’s is because its experienced managers already enjoy Alitalia pensions in addition to their salaries. The airline has tight turnaround times (40 mins) and it also interlines, maintains normal ticketing and CRS activities, participates in Swissair’s Qualiflyer FFP, and offers meals.

Air One added its first international route last spring — Milan Linate to London Stansted — but it has also had to curtail activity from some points, cutting services at Turin, for example. Inevitably there have been talks with Alitalia; last September Air One seemed to have signed a deal with Alitalia under which Alitalia would have used it as a low cost operation to Brussels, competing against Virgin Express/Sabena. But the agreement was called off at the last minute, perhaps because of pressure from antitrust authorities.

Air One’s main asset has been its grip on the Linate slots, and it has strongly opposed the planned transfer of flights to Malpensa from October 1998. But the opening of the new airport will leave the Rome–Milan route isolated in Linate, with Air One continuing to compete rather ineffectively against the Alitalia shuttle. Its fares are generally 20% lower than Alitalia’s, but this difference has not been enough to divert sufficient numbers of passengers nor generate new traffic (Air One’s load factors hover in the low 50s). So the Swissair/Air One collaboration agreement signed in December 1997 does not give Swissair a clear inroad into the Italian domestic market, and connecting internationally to Air One will need a redesign of Swissair’s operations. Such a redesign will probably be a pre–requisite for Swissair taking up its option to buy 30% of Air One.