The taxing question of airport charges

February 1998

European airport charges appear out of line with the US, but taxes distort the picture. And both systems are full of contradictions and inefficiencies.

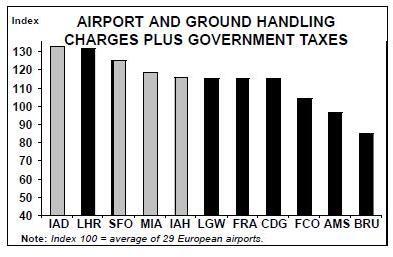

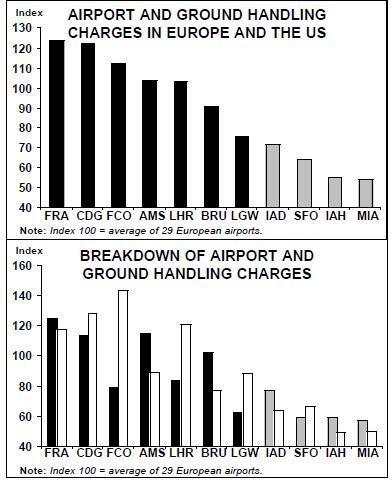

The issue of airport charges has been tackled in an AEA–commissioned study conducted by Cranfield University. Both airport charges (for runway, apron and terminal facilities) and handling charges (for passengers, baggage, etc) have been included. So a clearer picture of charges at an airport like Rome Fiumicino, which has low landing charges but very high handling rates, emerges.

Even the most expensive US airport in the sample, Washington Dulles, has unit charges below those of one of the cheapest European airports, London Gatwick, and half those of Frankfurt. Within Europe there is a remarkable and unreasonable variation among airports — charges at Frankfurt are 40% higher than Madrid and 20% higher than Heathrow.

Problems of comparison arise when government taxes are taken into account: it is argued that US passengers pay for infrastructural costs directly through ticket taxes, and if all the taxes collected by airlines through ticket taxes are taken into account then in theory the US airports become more expensive than the European. But the US 10% ticket tax and international departure tax of $12 per passenger is not a true user fee (and the UK government does not even pretend that its departure taxes are anything to do with aviation funding).

Moneys raised through the US taxes go into the Aviation Trust Fund (ATF) to be spent on ATC (in Europe en route charges are levied separately by Eurocontrol) and on airport development. But there was never any requirement that this money be spent on airports; rather surpluses were diverted to help balance the federal budget. Then, when Washington went on strike at various times in 1996 and 1997, Congress let the ticket tax expire and as a consequence the ATF was depleted.

Ticket taxes are also supposed to be the source of funds for the Airport Improvement Program, and in fiscal 1998 some $1.7bn will be available mainly for primary airports. But to get the funds airports have to battle among themselves and with the Appropriation Committees in Washington.

Changes proposed in the 1988 Tax Reconciliation Bill to the ticket tax — gradually reducing it to 7.5% by 2000 but adding fixed $1–2 fees per segment — have been justified on the grounds that the reformed tax will approximate to a user fee because it will now reflect the costs of connecting flights at a hub. The low–cost point–to–point operators simply see it as a means of transferring money from themselves to the larger hub and spoke operators.

Again though, the definition of user fee hardly applies because it appears that the bulk of the additional $3–4bn this new ticket tax is designed to raise over the next five years will disappear into general funding rather than being used for specific aviation projects.

So while the European airlines see US airport charges as reflecting efficiency and competition, US airlines tend to see their own system as an iniquitous bureaucracy.

Europe has its own unique tax distortion — duty–free sales. The exemption from consumer taxes on sales of alcohol and tobacco at airports and on ferries can be regarded as a subsidy — estimated by Goldman Sachs to be in the order of $2.2bn a year — by European taxpayers to airports and ferry operators. The EC has in effect taken this view and legislation to outlaw duty free sales could come into force as early as July 1999.

The severest impact will be on airport authorities which have developed the concession income side of their business — BAA, for example, which relies on duty free sales for about 29% of its total revenue. It will be allowed to recapture at least some of the lost revenue through increased aeronautical charges, and other airports will follow suit.

The other important piece of European legislation in this field is the Ground Handling Directive, which aims over the next four years to completely deregulate this activity. This year airlines will be allowed to self–handle at all airports without restriction. In 1999 at least one specialist handling company will be allowed to compete.

This at last offers relief to most European airlines (although it is a major blow to airlines like Iberia and Olympic, which operate near monopoly ground handling services at their home airports) There are two options for the airports. They can sign discounted contracts with their airline customers before the business is deregulated or they can sell off their ground handling businesses to specialist companies. Either way ground handling prices in Europe are going to be forced down.