United: the quest to unlock

full potential

December 2016

With a new leadership in place, labour deals done and operational reliability restored, United Airlines has unveiled ambitious plans to unlock the full potential of its assets and to close the operating margin gap with its peers. How will it achieve those goals?

When United and Continental completed their merger in October 2010, there was excitement about the enormous potential offered by that union. Many in the financial community believed that combining United’s powerful global network and well-located hubs and Continental’s highly regarded leadership team would quickly lead to industry-leading financial results.

Instead the new United has been a big disappointment. Six years on, it continues to underperform Delta and American in terms of RASM and profit margins, and the margin differentials have only widened over time.

There are many reasons for that underperformance: structural, self-inflicted, bad luck and competitors’ success.

The structural impediments include lower domestic hub concentration than at American and Delta, high costs at hubs such as Newark, exposure to the weak energy sector in Houston, and relatively heavy reliance on 50-seat regional jets.

The self-inflicted damage included a disastrous IT switchover in March 2012, which led to extensive operational and service issues. United’s inability to rectify the problems for months lost it many business customers and caused costs to soar.

The consensus is that United mishandled key aspects of the merger integration. With hindsight, some analysts have made the point that the team led by ex-CEO Jeff Smisek did not have hands-on experience in that area.

United’s problems have also included an unhappy workforce (historically so) and, as one analyst has suggested, an inconsistent flight experience and an “underwhelming value proposition to peers”.

Then there was the “chairman’s flight” scandal, which led to the resignation of Smisek in September 2015. (After a fateful dinner attended by Smisek and the leadership of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, United had introduced an uneconomic twice-weekly flight from Newark to Columbia, South Carolina, where PANYNJ’s chairman had a vacation home.)

United quickly found a promising new CEO, Oscar Munoz, who had extensive and broad experience in the transportation industry (most recently as president/COO of railroad operator CSX Corp), had demonstrated strategic vision and strong leadership in his previous positions, and had sat on Continental's and later United’s boards since 2004. But, unfortunately, Munoz suffered a heart attack just three weeks into his new job and subsequently underwent a heart transplant.

In early 2016, while Munoz was still on medical leave, an unusual boardroom fight developed involving two hedge funds — Altimeter Capital Management and PAR Capital Management. The activists alleged that United’s board lacked airline expertise and had provided insufficient oversight.

Finally, Delta’s incredible progress since its 2008 merger with Northwest, as well as its success in the New York market, and American’s successful reorganisation and merger with US Airways in late 2013 have also added to the pressures United faces.

However, Munoz has accomplished an impressive amount since he returned to his duties full time in mid-March.

First, the proxy contest was resolved amicably (in April) and, importantly, resulted in a much stronger board of directors. The hedge funds got their candidates in, while Air Canada ex-CEO Robert Milton joined the board as non-executive chairman. As a result, seven of the 14 directors and five of the 11 independent directors were new to the board.

Second, Munoz has had success in restoring the morale of United’s frontline employees — an area that he had initially focused on.

Third, Munoz has built an impressive senior leadership team. He completed the process in August by bringing in three new highly accomplished senior executives: American’s pricing/forecasting guru Scott Kirby as president, Andrew Levy as CFO (from the hugely successful ULCC Allegiant Air) and Julia Haywood as Chief Commercial Officer (from The Boston Consulting Group).

Fourth, United’s operational reliability has improved significantly this year. For example, the carrier has consistently ranked among the industry’s best in on-time performance, which improved by 10 percentage points in the first nine months of 2016.

Fifth, the airline has launched a “reimagined”, luxurious United Polaris international business class — another move that could win back customers. Polaris will take flight in early 2017 on United’s 777-300ERs, followed by 787-10s, A350-1000s, 767-300s and 777-200s.

Sixth, with the ratification of a new six-year contract by IBT-represented mechanics on December 5, United has now reached new joint agreements with all of its work groups. This is a major integration milestone that should unlock more merger benefits and further boost employee morale.

Seventh, Munoz has outlined his plans to improve United’s earnings, close the margin gap to peers and realise the carrier’s “full network, product and segmentation potential”.

In late June Munoz held an investor meeting to announce $3.1bn of value-driving initiatives by 2018. The ideas were well-received, though details were sparse and many analysts remained sceptical given United’s poor track record of delivering on its promises.

At its investor day on November 15, United outlined a more comprehensive and specific set of strategic initiatives aimed at generating $4.8bn in earnings improvement by 2020. It will be achieved through a combination of commercial initiatives, operational improvements and cost cuts.

Notably, United not only plans to close the operating margin gap with Delta, which it estimates is 5.6 points in 2016; it plans to exceed Delta’s margin by 1.5 points by 2020. United expects commercial initiatives to close five points of the gap, with operational improvements and cost cuts accounting for another point each.

The most important new strategies (discussed in detail in the sections below) are Basic Economy (a promising new no-frills domestic fare category), better revenue management and various network initiatives. Those three items account for $2.5bn of the targeted $4.8bn earnings improvement between 2015 and 2020.

United is also targeting a $1bn contribution in the plan period from existing re-fleeting and upgauging programmes. The latter include adding slimmer seats and replacing the smallest regional jets with larger models. Those programmes will increase the average seats per aircraft from 105 in 2015 to 119 in 2020.

United also intends to build on the success achieved with improving operational reliability. Further measures, such as shortening aircraft turnarounds and reducing long delays and cancellations, are expected to contribute $300m in earnings improvement by 2020.

The downside of clinching all the labour deals — and having what Munoz claims is an “energised” workforce — is a substantial hike in labour costs. United hopes to offset some of that with $700m of cost efficiency improvements in the plan period.

United won praise from the financial community at the investor day when it announced narrowbody aircraft order deferrals that will reduce capex by $1.6bn in 2017-2018. The net capex savings will be around $1bn because United also announced some new Embraer aircraft orders.

And recently-appointed CFO Andrew Levy outlined very sensible balance sheet and capital deployment strategies. He emphasised the need to maintain adequate liquidity and shareholder return programs (which may include a first-time cash dividend) but not fund the latter with borrowing.

The key question is: Will United be able to deliver? Many analysts have called the plan “aggressive” or “ambitious”. The stated aim to exceed Delta’s margins has raised a few eyebrows. (Delta is seen as a leader among the big carriers on the financial front, with an impeccable post-bankruptcy record of delivering and a habit of constantly raising the bar.)

JP Morgan analysts wrote that the plan was “characterised by both ambition and ambiguity” but that it represented United’s “first realistic path toward improved relative margins by decade’s end”.

More segmentation

At the investor day, United unveiled its version of Basic Economy — an unbundled, ULCC-type domestic fare category that was technically trademarked by Delta in 2014 but is now also being introduced by the other two of the US Big 3 during the first half of 2017.

Basic Economy is arguably the most important component of United’s new plan in that it should allow it to both take on LCCs/ULCCs more successfully and improve the yield from corporate customers. Delta’s experience has indicated that most corporations prevent their employees from booking those fares because of the onerous restrictions — and United’s version is more restrictive than Delta’s. In other words, as JP Morgan analysts put it, Basic Economy is effectively a “corporate fare increase”.

JP Morgan analysts wrote recently: “Apart from bag fees, we consider Basic Economy to be one of the industry’s most creative revenue concepts of the past decade”. And American, which expects to announce the details of its version of Basic Economy in January, has described it as a “game changer” that will allow it to meet competitors’ prices without the same amount of dilution.

United’s Basic Economy fare offers “the same standard economy experience” but seats are only assigned on the day of departure, the boarding takes place in “group five” and customers can bring only one personal carry-on item that must fit under the seat. Flight changes or upgrades are not allowed. Customers can continue to earn redeemable miles but not status miles.

The extremely restrictive bag rule is significant in that it will encourage more people to pay to check bags or select higher fare types that allow larger carry-ons. An added benefit is that it will simplify the boarding process as fewer people bring overhead bags on board. United will start selling Basic Economy in early 2017 for travel in Q2 and expects the fare type to boost its earnings by $1bn by 2020.

United is now evaluating another fare type — premium economy — for both domestic and international markets (analysts expect it by 2018). In this regard it is playing catch-up with American, which began rolling out its international premium cabin in October, and Delta, which has announced such plans for 2017. That type of cabin is already offered by a number of Asian and European operators and is being seriously studied by global carriers such as Emirates.

So the trend at US airlines, as elsewhere, is towards segmentation, which United notes is “part of a broader focus on personalisation”: customer expectations and behaviours are changing because of increased choice.

United’s investor day presentation noted that airlines have historically segmented on three dimensions — brand, fare rules and class of service. But now, consolidation has created fewer brands with broader offerings. Fare rules have eroded as LCCs and ULCCs are offering one-way fares with no advance purchase requirements. Airlines are now expanding their offering beyond the traditional two classes.

Better revenue management

It is hard to imagine that a global airline like United would not already have state-of-the-art, or at least adequate, revenue management systems, but that appears to be the case. The airline’s current system, Orion, built in 1997, has some known shortcomings. Specifically, since demand today is no longer independent for each product like it was 20 years ago, the system has a “problem forecasting small numbers” and much of it has to be done manually.

So United will be revamping its revenue management system to enable it to forecast demand more accurately. It will be done in phases under the guidance of new president Scott Kirby, who was famed for those skills at American.

Amazingly, the planned improvements to the demand forecasting system are expected to boost pretax earnings by as much as $900m by 2020. The first phase, to be implemented in 2017-2018, is estimated to improve unit revenues by 1-2 points. Subsequent phases, to be rolled out within three years, will have a similar PRASM impact.

Network and hub initiatives

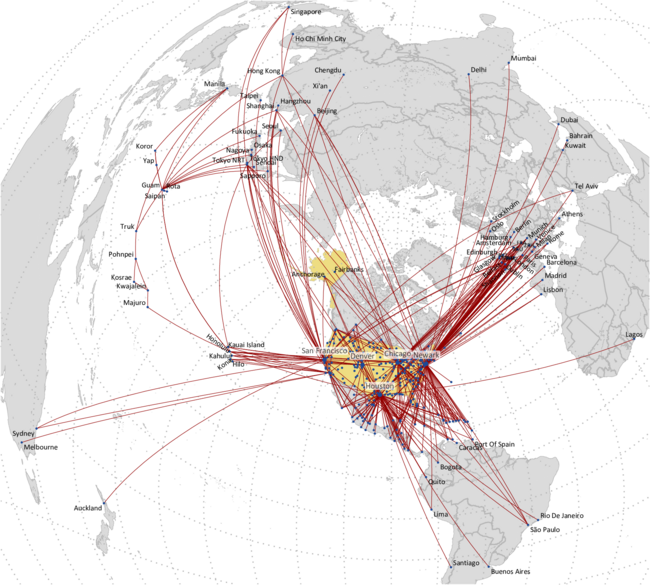

United has one of the world’s most comprehensive route networks and well-positioned US mainline hubs. With hubs serving the nation’s five largest markets (Newark, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and Washington Dulles), plus Denver and Houston (9th and 12th largest markets, respectively), clearly there is great potential to tap both international and domestic markets.

In the past, however, United focused on its lucrative international network and used the domestic market mainly to feed into international services. It “de-emphasised” domestic flying by operating smaller aircraft, offering lower frequencies and having less domestic connectivity than Delta and American.

But over the last five years, following consolidation, the domestic market has become the most profitable segment for the industry. While international remains highly profitable for United, the management feels that the biggest opportunity to improve earnings will now come from domestic flying.

So United will focus on strengthening its domestic profitability with strategies such as upgauging aircraft, de-emphasising regional operations and trying to boost connectivity. The latter means improving bank structures at key hubs such as Chicago, Houston and Newark. United will also work to improve schedules and the product in the top domestic business markets.

United feels that Newark is the “only true potential connecting hub in New York” and should be the leading airport in New York and across the Atlantic. But it lacks connectivity because of its “rolling departures and arrivals”.

At Chicago O’Hare, which is well-positioned geographically for connecting passengers, United has identified opportunities to add more cities in the catchment area and improve the bank structure.

At Houston, which is a strong Latin America gateway but currently suffers from weakness in the energy sector, United has gate capacity to re-bank its operations.

United remains committed to Washington Dulles, which is a high-cost airport but nevertheless a profitable international gateway.

Much of United’s recent international growth has focused on San Francisco, which it regards as the best gateway from the US to Asia. This year’s new 787 services from SFO have included Tel Aviv, Xi’an, Hangzhou, Singapore and Auckland.

Los Angeles is the second largest local market in the US (after New York) and a profitable international gateway for United, though United has found it difficult to connect to Star carriers there. It is trying to get more gates and improve connectivity at LAX.

United is the top US carrier to China, where it now serves five cities on the mainland. Beijing and Shanghai are served from four different US mainland hubs. China represents both an opportunity and a risk; the latter is because of United’s sizable exposure, should the world’s second largest economy experience a prolonged economic slowdown.

Like many of its peers, United has launched flights to Havana, Cuba in recent weeks, operating from both Houston and Newark. The industry verdict at this stage is that Cuba will be a tough market. United is reasonably well positioned serving it especially from the New York area, which has the second largest Cuban population in the US.

The cost challenge

United currently expects its non-fuel unit costs to rise by 3.5-4.5% in 2017, which is slightly higher than the 2.75-3.25% increase expected in 2016 and not too bad compared to what some other US airlines are projecting for next year.

Labour cost hikes will account for all but 0.5 points of the increase, i.e. 3-4 points. Half of the labour cost increase will come from new agreements ratified before December 2016, and the other half will be due to the IBT-represented workers’ contract and the automatic reset provisions in the pilot deal (to match the new Delta rate).

In October United’s leadership had some very positive things to say about the latest round of pay awards. CEO Oscar Munoz indicated that he was happy to grant the pay increases because “employees are very core to our product and customer experience”.

President Scott Kirby also phrased it nicely: “We can now give back, do great things for our people in contracts after the 15 years that they have been through — the post-9/11 era furloughs, concessions and losing seniority”. He said it was “rewarding” to be able to give those kinds of raises and economic benefits back to the workforce.

In other words, with profit margins at record levels and significant ROIC and free cash flow being generated, US airlines can now easily afford to give decent pay awards to their workers. Airlines are a service business and will reap benefits from having happy and engaged employees.

But United has identified $700m of new cost savings by 2020 from increased operational efficiency, better utilisation of assets and people, strategic purchasing and new technology.

In part because of those savings, United expects to keep average annual non-fuel CASM growth below 1% in 2018-2020. That assumes ASM growth averaging 1.5% annually. The pilot agreement becomes amendable in 2019 and all other labour agreements after 2020.

Some analysts consider the long-term cost guidance bullish. But if United can achieve those projections, it has a decent chance of closing the operating margin gap to its peers.

Trimming capital spending

The $1.6bn capex reduction in 2017-2018 that United announced at investor day was a result of a restructuring of earlier orders for 65 737-700s. 61 of the aircraft were converted to the 737 MAX (for post-2018 delivery), and the other four were converted to the 737-800, for delivery in the second half of 2017.

Separately, United agreed to purchase 24 E175s from Embraer, instead of leasing them. The aircraft were part of a capacity-purchase agreement with Republic, which was modified during the regional partner’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy. United said that the order, which increased planned capex by $550m, lowered the cost of capital, representing an NPV benefit of $100m compared to the lease agreement.

The resulting net capex saving of $1bn was well received, as previously United had planned to ramp up aircraft spending over the next few years.

United is also in the process of undertaking a review of its long-term fleet commitments. With the focus being on capital efficiency, it is considering adding more used aircraft (over the 11 used Airbus aircraft it is already due to receive in 2016-2017).

In recent weeks it has been reported that United is reviewing its $12.4bn order for A350-1000s, with the view of altering it to include smaller long-haul models. United is reportedly also considering the MAX 10X to replace some of the recently-deferred narrowbody orders.

Earlier this year United converted some of its post-2020 787 orders into 777-300ERs and 787-9s, for delivery from 2017, which will facilitate an accelerated retirement of its 20 remaining 747s by the third quarter of 2018.

United will debut the 777-300ER at its Newark and San Francisco hubs in early 2017, and the type will replace 747-400s on the San Francisco-Hong Kong route in March. It will be the first aircraft to feature the Polaris business class. The airline expects to place into service all 14 ordered 777-300ERs by the end of 2017.

United’s total capex is now projected to be $4.2-4.4bn in 2017, but it will decline to the $3.3-3.5bn range in 2018 (both years include $1.1bn of non-aircraft capex).

The fleet plan has significant flexibility. By 2020 the fleet will include around 330 unencumbered aircraft (up from 250 currently), plus some 120 aircraft that could be returned to lessors.

| Total | 900 | 1,800 | 3,150 | 3,950 | 4,800 | |

| $m | 2016E | 2017E | 2018E | 2019E | 2020E | Unique United levers v Delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial enhancements | ||||||

| Network initiatives | 100 | 300 | 450 | 600 | ~100% | |

| Re-fleeting and upgauge | 400 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1,000 | ~50% |

| Segmentation | 200 | 550 | 700 | 1,000 | ~25% | |

| MileagePlus enhancements | 250 | 100 | 300 | 300 | 300 | ~100% |

| Revenue management improvements | 100 | 400 | 700 | 900 | ~75% | |

| Improved operations | ||||||

| Operational integrity | 50 | 200 | 300 | 300 | 300 | ~100% |

| Cost structure | ||||||

| Cost efficiency program | 200 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | ~50% |

Source: Company presentation.

| Total Fleet | 1,236 | 1,226 | 242 | |

| Aircraft type | YE 2015 | YE 2016 | Orders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainline fleet | 747-400 | 22 | 20 | |

| 777 | 74 | 75 | 14 | |

| 787 | 25 | 30 | 21 | |

| A350 | 35 | |||

| 767 | 51 | 51 | ||

| 757 | 81 | 77 | ||

| 737NG | 310 | 325 | 73 | |

| 737 MAX | 99 | |||

| A320 | 152 | 158 | ||

| Mainline Aircraft | 715 | 736 | 242 | |

| Regional | Dash-8 | 34 | 21 | |

| ERJ 135/145 | 204 | 188 | ||

| CRJ200/700 | 165 | 129 | ||

| E170/175 | 118 | 152 | ||

| Regional Aircraft | 521 | 490 | ||

Source: Ascend, Aviation Strategy

Note: Azimuthal equidistant map projection centred on Chicago. Great circle routes appear as straight lines.

Note: 2016 and 2017 are analysts' consensus estimates as of December 12.

Source: Company reports

Note: Aircraft leases capitalised at 7x

Source: Company presentation