Why can’t Africa

be more like India?

December 2016

Whereas the airline sector in India has been transformed over the past ten years, Africa has stagnated. LCCs have proliferated in India, but they have hardly got off the ground in Africa, and Fastjet has come to symbolise their failure.

Much was hoped for with Fastjet, which promoted itself as the first pan-African LCC, made presentations that sounded very convincing (or convincing enough to raise several tranches of funding on London’s AIM). But the airline produced a series of very poor results, and its losses for the first half of 2016 were disastrous: a US$31m operating loss on revenues of $33m. The A319 operation has in effect been shut down, the main base moved from Tanzania to South Africa and the fleet downsized to Emb195s. The management, formerly led by CEO Ed Winter, have gone.

To be fair, Fastjet did some things right. It created a transnational brand (the Grey Parrot), promoted new distribution methods suited to Africa, notably bookings and payments via mobile phones, “educating” passengers about the LCC operation (most basically, this meant persuading passenger that the flight would take off as advertised) and its fleet was comprised of modern A319s, replicating on a very small scale the easyJet model.

There was unfortunately a list of formidable errors made by Fastjet.

- The purchase of Fly540 from Lonrho was intended to facilitate multinational operations through the acquisition of various AOCs. In fact, the political barriers remained, and Fastjet found that it had bought a lot of hidden liabilities.

- Largely as the result of the Fly540 purchase, Fastjet found itself with far too many flying and other personnel, so that its efficiency ratios resembled that of a hopeless state-owned airline rather than a LCC.

- Similarly, its aircraft utilisation and load factors were nowhere near LCC standards as it struggled to find viable routes to operate on.

- Its choice of a main base at Dar-es-Salaam was probably a mistake as there were simply insufficient volumes to grow from there. Political instability in Tanzania was another factor.

- The airline was unwilling and/or incapable of breaking into Africa’s key markets — Nigeria and South Africa — and instead focused on expanding in competition with Kenyan Airways on Tanzania-Kenya, and expanding from Tanzania to Uganda and Zimbabwe. It now plans to grow its operation between Harare and Johannesburg, but with Emb195s rather than A319s, and in competition with Comair.

- The management structure was fundamentally flawed. The airline’s headquarters was situated at London Gatwick where the top executives obviously preferred to stay while operations were directed from the Dar-es-Salaam base. This just seems all wrong for developing local expertise and understanding the African experience.

- Similarly, bringing in Sir Stelios Haji-Iannou and granting him a substantial shareholding was plausibly seen as way of giving confidence to investors, but it all ended with acrimonious criticism and hefty consultancy fees.

Harnessing African entrepreneurship, of which there is a plentiful supply, into a start-up airline project, is an essential, as is blending local with global capital. Much easier said than done, of course.

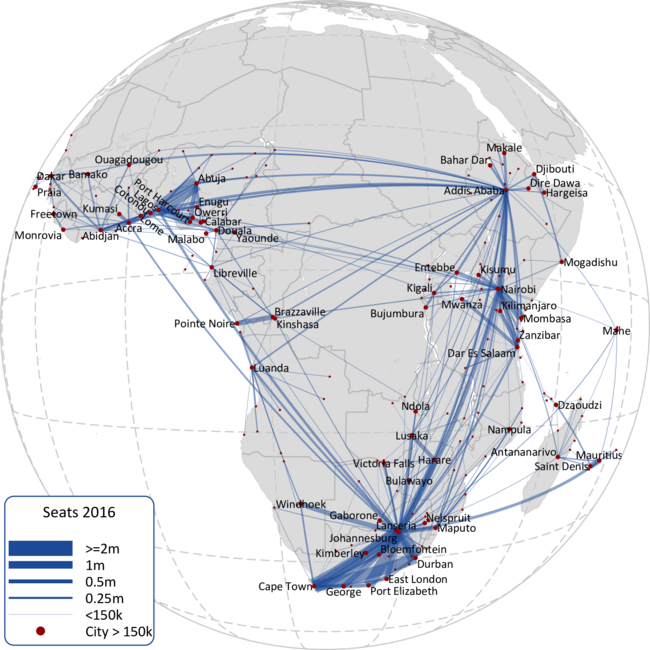

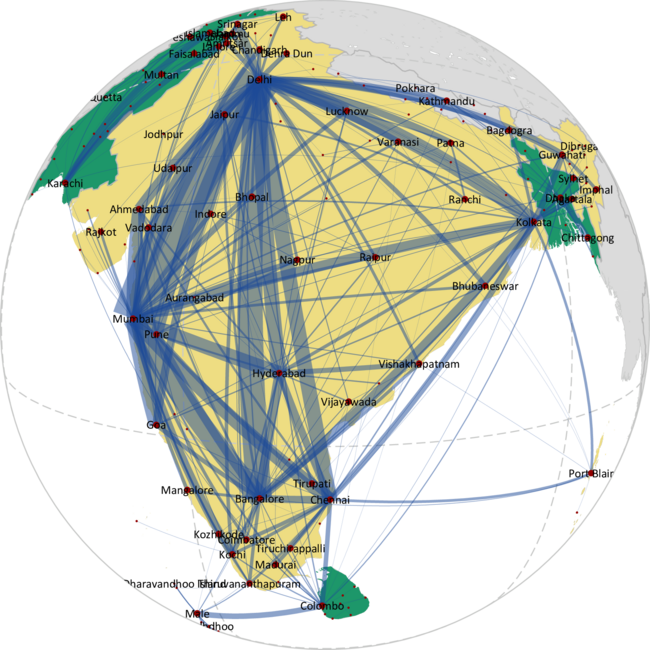

And the market opportunity remains an LCC start-up. The pie charts below show a contrasting picture in the Indian sub-continent and sub-Saharan Africa.

About 66% of Indian internal capacity is now provided by new LCCs in contrast to roughly zero ten years ago, though the state-owned Air India (formerly Indian Airlines) still has a market presence domestically, as does Jet Airways, unprofitable but supported by Etihad.

The development of the Indian LCC model has stimulated a surge in domestic traffic — to around 80m passengers from 14m ten years ago — and resulted from a number of inter-related factors.

- The emergence of the an Indian “middle class” with the propensity and income to fly. Estimates of this middle class were around 200m out of of a total of1.4bn, similar to the numbers that have been quoted for the African continent, though recent studies have questioned the definition of middle class and downsized the relevant populations.

- Very, very slow alternative transport on the railway in India. In planning for one of the LCC start-ups — SpiceJet — we were able to use Indian Railways’ meticulously compiled data for travel in air conditioned coaches to estimate a base traffic load for an LCC. No such data applies in Africa, but there is plenty of information about the state of roads in, for example, Nigeria.

- The Indian authorities began to liberalise aviation, not in one big bang but gradually, starting with the dismantling of traffic allocation rules (which meant that to fly Mumbai-Delhi, one had to commit to flying a proportion those ASKs on other metropolitan routes and another percentage on remote tertiary routes) and leading to the abandonment this year of the 5/20 rule (5 years experience and a fleet of 20 before being permitted to fly internationally).

- Global capital became interested in the returns possible through investing at the start in Indian LCCs (see Aviation Strategy, October 2015 for IndiGo’s success story) and was able to ally with local sources of finance. Ex-pat airline executives, a notable example being Rakesh Gangwal, who, among other achievements, was a CEO of USAirways, returned to India.

The economic geographies of India and sub-Saharan Africa are of course different. In India flight sectors are typically 1-2 hours, perfect for LCCs, there is a wide spread of important cities beyond Mumbai and Delhi, and the internal traffic is mostly point-to-point rather than connecting.

The African map reveals two major aviation zones — South Africa, by some way the biggest, and Nigeria — unsurprisingly coinciding with the centre of economic activity and population, with a lot a blank spaces. East Africa, where Fastjet concentrated its operations, is not on the same scale.

The bar chart shows two things: first, the top 20 city-pairs in India are all markedly larger than the equivalents in Africa, and, second, that almost all the top 20 city-pairs in Africa are either in/to/from South Africa or in/to/from Nigeria.

Going back to the African capacity pie chart, there are only two substantial African flag-carriers left — the dysfunctional SAA and the relatively successful Kenyan, and there are no pure LCCs. The closest is Mango but that is a 100%-owned subsidiary of SAA. Operating ten 737-800s, Mango has achieved a good reputation and has usually reported profits, though its results are consolidated opaquely in SAA’s financials. It looks, however, as if 2015’s net profit of R38m will turn into a loss of to R37m ($3m), with the local press speculating that Mango is being “squeezed” by SAA. Incidentally, former Mango CEO, Nico Bezuidenhout, now heads up the resurrected Fastjet.

Comair, a BA franchisee and 11.5% owned by IAG, is probably the continent’s most successful short haul airline. Operating a fleet of 17 737-400 and -800s with another eight MAXs on order, the airline has been consistently profitable for the past ten years. Its results for the year to June 2016 show revenues of R5.9bn ($470m) and profits of R193m ($15m).

These two airlines plus the state-guaranteed SAA make South Africa a difficult market for an LCC new entrant. Nigeria should be a different prospect (should being the key word as politics tend to frustrate in that country). A prosperous middle class, even if only 10% of the 200m total population, a trading mentality and, until recently, fast GDP growth form the background. In terms of economic geography there is very strong triangle — Abuja- Lagos -Port Harcourt — and various other important points with very poor roads in between.

The airline competition appears weak but is obstinate, surviving financial crises, exchange rate shortages and sometimes dodgy safety records. Arik has a fleet of 25 jets and turboprops, with seven types in all; no financials are available. Aero Contractors operates seven aircraft, 737s and Dash 8s, and is partly owned by a Nigerian government body following a bail-out in 2013; no financials are available.

Jim O’Neill, former chief economist at Goldman Sachs, when developing his treatise on MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey — the developing economies that have the potential to become drivers of global growth) has commented that what Nigeria needs most urgently is a regular electricity supply.

An effective, dynamic LCC would help greatly as well.

INDIAN SUB-CONTINENT AND AFRICA

Note: Thickness of lines directly related to number of seats

Note: Thickness of lines directly related to number of seats