Virgin America: Scaling back to attain profitability

December 2012

In mid-November Virgin America finally did the sensible thing: reduced and deferred its substantial A320 order commitments, to drastically scale back growth and preserve its balance sheet. Because of continued financial losses, the award-winning San Francisco-based LCC, which has grown at a dizzying pace in the past two years, was in no position to start taking deliveries in mid-2013 of the $5.1bn, 60-aircraft A320/A320neo order placed in January 2011.

Under the revised agreement with Airbus, Virgin America’s A320 orders have been reduced from 30 to 10 and deliveries rescheduled from 2013-2016 to 2015-2016. The 30 A320neo positions have been deferred by as much as four years, from 2016-2018 to 2020-2022.

The first concrete signs of capacity discipline at Virgin America came in mid-October, when CEO David Cush told employees that the airline would cut ASMs by 3% in 1Q13 and offer staff voluntary unpaid leaves.

After adding 24 aircraft since 1Q10 to bring its fleet to 52 A320s, Virgin America now plans to take just one additional leased A320 (in March 2013) until the rescheduled deliveries from Airbus start in the second half of 2015. Its ASM growth will decelerate from 28% annually in the past three years to a “mid single-digit” annual rate over the next several years.

Of course, Virgin America will still be able to undertake exciting new expansion. On that front, there was a major breakthrough in early December: the airline secured long-coveted access to Newark, which will now be added to the network in April 2013.

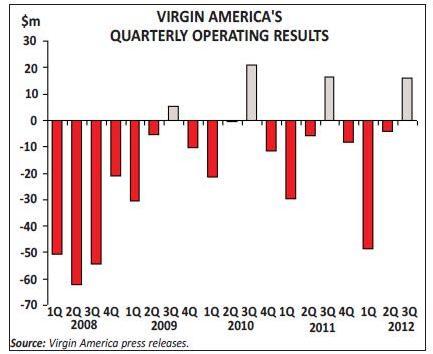

The order deferral announcement came as Virgin America reported a $12.6m net loss and a meagre $15.8m operating profit (4.3% of revenues) for the September quarter, the industry’s seasonally most lucrative period. The January-September net loss was $120.4m, almost double the year-earlier loss. Virgin America has incurred net losses totalling $580m since the beginning of 2008,

Virgin America has benefited from deep-pocketed and patient investors, including Cyrus Capital, which recapitalised it in late 2009 and helped it raise $150m through a debt offering in December 2011. Of course, its survival is also important for the Virgin Group of the UK, which holds a 25% voting stake and a 49% economic interest (the maximum foreign investment level in airlines allowed by US law).

But Virgin America’s cash reserves, which were boosted by the debt offering to a relatively healthy $160m at the end of 2011 (15.4% of annual revenues), have dwindled alarmingly this year. At the end of September the carrier had only $75m in unrestricted cash – just 6% of lagging 12-month revenues.

Further shareholder funds are probably not forthcoming as long as the losses continue; that was certainly the impression gained earlier this year when Virgin America’s top management commented on longer-term funding plans. Nor is an IPO possible until the airline has a profitable year under its belt. Therefore Virgin America is under enormous pressure to become profitable.

It is perhaps not surprising that the naysayers have been out in force in recent weeks. “Why an airline that travellers love is failing”, read a headline in Time magazine in late October. “Is Virgin America on the ropes?” asked one business travel blog last month.

Among the more informed critics, Wolfe Trahan’s outspoken airline analyst Hunter Keay, in a note to clients in October, criticised various aspects of Virgin America’s business model and growth strategy and questioned its ability to survive absent a “major restructuring”.

As reported by Bloomberg, Keay criticised Virgin America, first, for what he called “network missteps into highly trafficked markets”. Virgin America has competition on every one

According to a late-November analysis by CAPA, even at its SFO home base Virgin America is a distant second to United with an 11% seat share, compared to United’s 44% (November 19-25 data). At LAX, its second largest base, Virgin America’s 5.5% seat share makes it fifth behind American, United, Delta and Southwest. Virgin America has a “commanding” seat share in only one of its top ten domestic markets (the leisure-oriented SFO-Ft. Lauderdale route), and in several markets it is ranked third or fourth.

CAPA argued that Virgin America faces “formidable challenges” in competing against the numerous and different types of operators in nearly all of its top markets. It is aggressively trying to capture passengers from the legacies, which offer convenience and powerful FFPs, while competing on price with other LCCs, some of which also have attractive products for business travellers.

Nor is CAPA impressed by Virgin America’s Mexican strategy, which it felt reflected an “identity crisis”. The article argued that the very limited presence in leisure-oriented markets (three destinations in Mexico and two in Florida) “does little to create a foundation to sufficiently grow revenues to create sustained profitability, and likely deflects time and resources away from the carrier’s attempts to build up a more lucrative corporate base”.

CAPA concluded that while slowing growth and reducing aircraft commitments were prudent moves, Virgin America “also needs to make structural network adjustments to attain long-term revenue benefits”.

Mature versus new markets

If Virgin America does not stem the losses in the short-to-medium term, it would of course be likely to rethink its strategy. But it would probably have already, as a matter of course, suspended routes that were not meeting expectations. LCCs are nimble and usually get out of poorly performing markets quickly. When its first international route, San Francisco-Toronto, turned out not to have sufficient demand, Virgin America terminated it after just 10 months in April 2011.

Furthermore, there is currently no clear evidence that Virgin America is in the wrong markets; rather, the problem may simply be that it has too many new markets and not enough markets that are in the “mature” phase.

Rapid growth can put enormous pressure on airline profit margins, and Virgin America has grown extremely rapidly in the past two years. Between 3Q10 and 3Q12, its ASMs surged by 73%, compared to the US industry’s essentially flat capacity in that period.

CEO Cush said in mid-November that Virgin America’s core markets – those operated longer than 24 months – achieved an operating margin of 8% in the third quarter and were profitable year-to-date. “This strong performance in mature markets was offset by weaker performance in newer destinations added during the rapid two-year growth phase”. Back in the summer, Virgin America executives said that the SFO hub and mature markets out of LAX were “solidly profitable”.

“Percentage of new markets” and “percentage of mature markets” may sound like wishy-washy metrics or excuses, but they can be important determinants of profitability for LCCs and growth airlines generally.

JetBlue’s experience is illustrative. Ceasing growth and allowing the percentage of “mature” markets to increase has certainly made a big difference to its profits in recent years. Back in 2005 and 2006, JetBlue saw its net results turn negative due to over-aggressive expansion. But JetBlue acted quickly to curtail capacity growth and brought capital spending to relatively modest levels. In 2008-2009 its ASMs remained relatively flat and it returned to healthy (high-single digit) operating margins. JetBlue has since then stepped up growth a little, but it is now outperforming its peers financially and is committed to “sustainable” growth. At its analyst day in February 2012, JetBlue disclosed that 86% of its ASMs are now in markets where it has been for three years or more, compared to 55% in 2007. And only 5% of its ASMs are now in “new” markets (which it defines as “less than one year”), compared to 17% in 2007.

The other interesting point JetBlue has made is that its business markets in Boston (where it spotted a “once in a lifetime” type growth opportunity a few years ago as a result of legacy carrier withdrawal) take quite a bit longer to mature than its traditional leisure/VFR markets. In a typical Boston business market, the first year is lossmaking, the second year is roughly breakeven and the third year is profitable.

The fact that Virgin America’s recent growth spurt has included some of the country’s largest business markets, where it has aggressively courted business traffic with its upscale service, may have added to the delays in attaining profitability. The profit potential is there but it just takes longer. The major new markets have included Dallas Fort Worth (December 2010), Chicago O’Hare (May 2011), Philadelphia (April 2012), Portland (June 2012) and Washington DCA (August 2012).

Virgin America’s five-year loss record is sometimes compared to the virtually immediate profits and subsequent 17% operating margins JetBlue achieved in its initial years. But that really isn’t fair: in the early 2000s oil prices were in the $20-30 per-barrel range, compared to $80-90 currently.

Virgin America had little chance to earn profits in its initial years, because it had a uniquely slow and difficult start. Its launch was delayed by two years due to questions about its ownership and control structure, so it launched into the tough economic environment (the 2008 oil price surge, followed by the global recession). Then in 2009 one of its founding investors exercised an option to sell their stake back to the Virgin Group, which led to an almost year-long DOT enquiry about the airline’s US citizenship status. Virgin America lost about a year of growth since it was unable to obtain any aircraft financing during the DOT enquiry.

After a successful recapitalisation and DOT clearance, Virgin America staged its second “take-off” in January 2010. The airline began rounding up aircraft and announcing network expansion. In the subsequent 12 months its network expanded from the previous transcon/West Coast focus (SFO, LAX, JFK, Washington Dulles, Boston, Ft. Lauderdale, Seattle, Las Vegas and San Diego) to include Orlando, Dallas Fort Worth, Toronto and two points in Mexico.

But difficulties in obtaining gates and slots at desirable airports continued to impede Virgin America’s progress. It was not until the spring of 2011 that it gained access to Chicago O’Hare – a result of Delta and Northwest consolidating operations after their merger and being forced to renegotiate contracts with the airport. In April 2012 Virgin America added service to Philadelphia from both LAX and SFO. It was also able to begin daily flights to Washington DCA from SFO in August, thanks to a relaxation of a law from the 1960s.

Virgin America needs primary markets to become profitable, especially because of its desire to attract business traffic. Of course, in those markets it will clash mightily with the legacies. DFW is American’s stronghold. O’Hare is a hub for both American and United. Philadelphia is a hub for US Airways. Virgin America was not even able to secure a monopoly on the new SFO-DCA route, because the second daily frequency it had sought was awarded to United.

The opportunity at slot-constrained Newark came because AMR needed to restructure its lease agreement to reduce costs, as part of its Chapter 11 reorganisation. AMR gave up three of its six gates, one of which will go to Virgin America (the airport will control the other two gates). Fares at Newark are quite high and the airport is keen to attract more competition.

Newark will be Virgin America’s biggest-ever city launch: three daily flights from both SFO and LAX – all from day one. The flights will match the carrier’s JFK services. This is an extremely important development because, in addition to being better able to tap into the huge New York local/business market, Virgin America will be able to connect with more of Virgin Atlantic’s transatlantic services.

CEO Cush noted that, including Newark, Virgin America will be present in eight of the top 10 business markets from both SFO and LAX. The two major omissions are Atlanta and Houston.

Adding more north-south leisure-oriented routes might not be a bad idea either, because those markets peak in the winter when Virgin America’s transcon routes often underperform. Other upmarket LCCs have found Caribbean and Mexican expansion to be highly profitable. Many of the markets have significant VFR traffic, which makes them more recession-resistant.

Superior product,

aggressive tactics

Two things really differentiate Virgin America from other US LCCs. First, the Virgin brand has been a huge hit in the marketplace. Second, Virgin America uses aggressive competitive tactics by US airline standards.

Calling itself “the airline that is reinventing domestic travel”, Virgin America offers an upmarket product that features “mood-lit” cabins, superior in-flight entertainment systems and other amenities. It continues to win rave reviews from customers and sweep the “best airline” type awards.

Like JetBlue, Virgin America is popular enough to get away with not always having the lowest fares in the market. However, it is often the low-fare leader on transcon routes.

Virgin America has developed an attractive niche as SFO’s hometown or business airline. The product has been keenly embraced by the typical younger Silicon Valley business travellers, as well as small and medium-sized businesses in the Bay Area generally.

Among LCCs, Virgin America has been closest to industry average RASM because of its full GDS participation right from the start, three-class service, upmarket product, extensive use of alliances and legacy-style revenue management.

One of Virgin America’s main challenges in attracting business travellers is its inferior FFP (compared to legacy carriers’ programmes). It has tried to tackle that problem head-on this year. First, in August it launched an upgraded FFP that, like typical legacy FFPs, includes elite tiers allowing members to enjoy priority check-in, boarding, upgrades and other perks. Second, in mid-November Virgin America began aggressively wooing American’s and United’s FFP members by offering them an elite status match programme.

In another move to enhance offerings to business travellers, this month Virgin America opened its first airport lounge, “Virgin America Loft”, at LAX. FFP members will receive a select number of complimentary day passes to the lounge each year, and the passes can also be purchased for $40.

Virgin America’s strategy of venturing into numerous legacy hubs and routes where the large carriers are entrenched contrasts with the more cautious approach adopted by other US LCCs. JetBlue, for example, is going after business traffic only in Boston; in New York, where the legacies are battling for premium market share, JetBlue remains firmly focused on leisure traffic.

Virgin America’s tactics have been particularly aggressive in DFW, where it has found it tough to compete on AMR’s home turf. The past year has seen intense fare wars and provocative marketing campaigns, such as one where DFW flyers were encouraged to “dump their old airline” and “make the switch to a younger, hotter ticket”.

One positive development is that Virgin America is trying to strengthen its revenue management by bringing in an experienced (ex-Jetstar, ex-Delta) industry veteran to oversee that department from January.

Profits on the horizon?

Virgin America’s management has said that the two-year growth spurt was necessary to “establish a core network and to achieve economies of scale”. Now that growth has slowed, the airline can focus on “maximising the value of our network, instead of managing additional capacity”. In a Wall Street Journal interview, Cush said that the airline expected to open just 2-4 new cities over the next several years.

As of mid-November, Virgin America was expecting an operating profit in the fourth quarter. Of course, with operating and net losses totalling $36.8m and $120.4m in the nine months ended September 30, it would be too late to rescue the 2012 results.

But Virgin America is targeting profits in 2013. It would seem to have a reasonable shot at achieving that, as long as the economic and demand environment does not deteriorate significantly. With only modest new expansion, the percentage of mature markets will rise. With the elimination of past years’ heavy spending to facilitate growth, ex-fuel unit costs should fall at last. Also, the post-2009 operating losses have been relatively modest (1.7-3.7% of revenues).

While Virgin America has been quite successful on the revenue side, its cost performance has been dismal. Shockingly, its ex-fuel CASM has not improved at all in the past four years, remaining at the 6.5-cent level, despite significant fleet and ASM growth.

This year’s financial results deteriorated in part because of a difficult transition to the Sabre reservations platform in 1Q12. Similar to the experience of other US airlines, the move caused website issues and revenue management challenges. But Virgin America is likely to start reaping the full benefits of Sabre in the next year or two. The move ensured that it will have a stable and resilient platform for long-term growth.

The Sabre platform is important because it will facilitate more interline partnerships, full codesharing and other types of deeper cooperation with other airlines. Because even though it is now likely to turn profitable, Virgin America is not well-positioned in the US market with a mere 20-city network and a 50-something fleet. To be truly attractive to the business traveller, it needs to build a bigger network, covering all the key business destinations, and a competitive schedule throughout the day. It probably also needs to be bigger to achieve decent economies of scale.

Alliances will help fill some of those gaps. One immediate benefit of Sabre has been the tightening of links between the Virgin Group carriers. In the spring of 2012 Virgin America, Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Australia linked their FFPs, allowing each airline’s loyalty programme members to earn and redeem points across the combined network. In May they launched a joint “Virgin Skies” advertising campaign. In July Virgin America began limited codesharing with Virgin Australia via LAX.

In recent months Virgin America has signed similar deals with Hawaiian and SIA. Hawaiian has also become the airline’s first non-Virgin family FFP partner; the ability to offer travel rewards to Hawaii makes Virgin America’s FFP significantly more attractive. The SIA codeshares, which begin this month, entail SIA placing its code on select VA flights.

Delta’s acquisition of SIA’s 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic and the subsequent plans announced by Delta and Virgin Atlantic for an immunised New York-London JV are probably good news for Virgin America. The stronger transatlantic operation would lead to increased feed to Virgin America’s transcon services, even if most of the traffic will connect to Delta’s US network. The Virgin brand is apparently not threatened. There may even be opportunities for Delta and Virgin America to cooperate.

Like JetBlue, WestJet and Gol, Virgin America probably has the most to gain from the “open architecture” strategy that allows it to freely partner with multiple airlines. It has so far secured 19 interline partners.

The Airbus order deferrals removed pressure to complete an IPO in 2013, but given that it is already in its sixth year, having achieved “major carrier” status with over $1bn revenues in 2011, and with a fleet plan to fund from 2015, Virgin America will be looking to go public at the earliest opportunity. If it becomes profitable in 2013, it could potentially enter the public markets in 2014.