AMR's bankruptcy: Implications of the last US Legacy restructuring

December 2011

American Airlines and its parent AMR Corp filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on November 29 – a fate that many considered inevitable given AMR’s severe cost disadvantages arising from the fact that it had never restructured in bankruptcy. Though painful for stakeholders, the reorganisation should be successful for AMR, enabling it to close the cost gap, and also beneficial for the rest of the US airline industry.

AMR’s exact plans are not yet known, and in any case the Chapter 11 process can be unpredictable. But, as might be expected, speculation is rampant on the details of the restructuring and likely implications.

One interesting question is how much AMR might shrink in Chapter 11. New CEO Tom Horton has signalled only a “modest” reduction in flying; after all, American has already been demoted from the largest US airline to number three as a result of the Delta–Northwest and United–Continental mergers. But many analysts believe that AMR will shrink by as much as 10%.

But wouldn’t that only widen AMR’s revenue gap with competitors? After the shrinkage, will AMR then need to bulk up and increase scale in order to close the revenue gap with Delta and UAL?

Predictably, US Airways is again being touted as a merger partner for AMR as it reorganises. But what are the odds of such a merger taking place?

Another interesting question is whether AMR will be able to keep the 737 MAX orders placed in July (see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2011).

Most controversially, will AMR terminate all of its traditional pension plans? With the plans being underfunded to the tune of $10bn, it would be the largest pension default in US history.

Finally, how will American’s difficult labour relations play out during and after Chapter 11? The unions are gearing up for a major battle, with the pilots reportedly considering hiring Wall Street investment bank Lazard to advise them in the contract talks.

Why Chapter 11?

AMR came very close to filing for Chapter 11 in the spring of 2003, averting it only when it secured $1.8bn of annual labour concessions literally on the courthouse steps. But subsequently four of its key competitors (UAL, US Airways, Delta and Northwest) achieved much greater savings in bankruptcy in 2002–2007. Those airlines slashed their labour and aircraft ownership costs and dramatically reduced their pension obligations. AMR ended up with a significant labour cost disadvantage.

Then all of AMR’s concessionary labour contracts became amendable in May 2008 and the workers began to demand substantial pay increases. Although new contracts have recently been clinched with two smaller labour groups, talks with the critical pilots’ union have gone nowhere.

Over the years AMR has been remarkably successful in reducing non–labour costs, leading to a significant narrowing of the overall cost gap with competitors. Nevertheless, AMR continued to be hampered by serious disadvantages that are not easy to fix outside bankruptcy: a fleet that includes 200–plus fuel–guzzling MD80s, the massive pension deficit and a heavy burden of debt and leases.

To add to the woes, in recent years AMR’s key competitors have gained scale and strength through mergers, while AMR has been left out in the cold. And AMR suffered long delays in its global alliances efforts; notably, it waited a decade to secure transatlantic ATI with British Airways.

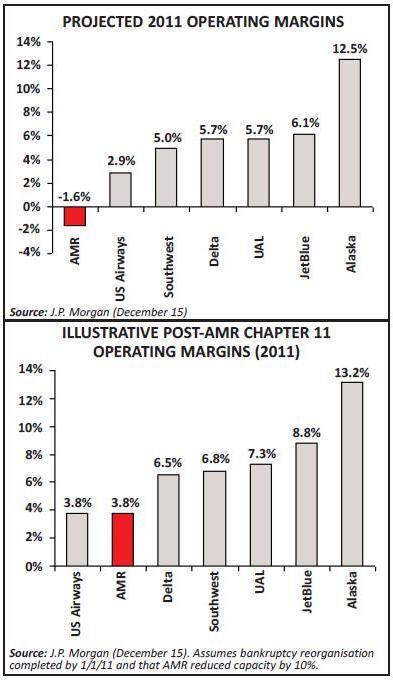

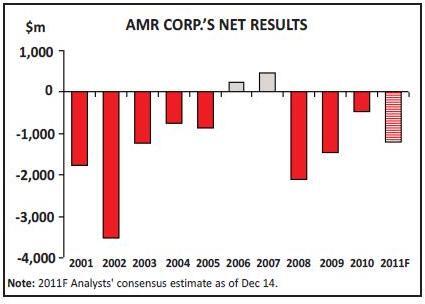

As a result, AMR has had only two profitable years in the last decade (2006 and 2007). It incurred net losses totalling $12.2bn in 2001–2010 and is headed for another $1bn–plus net loss in 2011. It is not even likely to break even on an operating basis this year (see chart, below).

Until very recently, AMR had pinned its hopes on two potential remedies (in addition to securing cost–effective contracts with its unions). On the cost side, it was counting on there being a convergence of labour costs over time, as competitors will not be able to sustain the labour rates and benefits secured in bankruptcy. On the revenue side, AMR has been engaged in an all–out effort to bolster its global and domestic presence particularly in business markets through alliances/JVs and by switching capacity to five “cornerstone” markets in the US.

The problem with those remedies was that the results were too slow to materialise. The expected convergence of labour costs will take years. The $500m in annual revenue benefits from the JVs and the cornerstone initiatives will not be realised until the end of 2012. In the meantime, AMR has continued to under–perform the industry in PRASM, amid signs that it is losing corporate market share to the larger competitors.

So, AMR fought long and hard to avoid bankruptcy. The events of May 2003 had been a painful experience for both labour and management and had involved the resignation of the popular chairman/CEO Don Carty. In the subsequent years the management frequently spoke of the company being “very mindful of that experience”. Gerard Arpey, who took over from Carty as CEO, was particularly determined to get new labour deals in place outside of bankruptcy. As recently as early October, the company released a statement saying that it was not its goal or preference to go into Chapter 11.

The bankruptcy filing came a few weeks after American’s pilots rejected a contract proposal, though further negotiations under a federal mediator were still planned and AMR still had an ample $4.1bn in unrestricted cash reserves (18.5% of last year’s revenues). It seems that AMR’s board saw no early resolution to the pilot talks and concluded, also in light of the global economic turmoil and the high and volatile oil prices, that it was prudent to file now while the company still had adequate financial resources for the reorganisation. Rating agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P) observed that AMR “likely would have faced cash pressures by late 2012 and had heavy debt maturities ($1.7bn) next year”.

The bankruptcy filing meant a change in leadership. Despite the board’s request that he stay, Gerard Arpey opted to retire. His right–hand man, president Tom Horton, was named chairman/CEO. Horton originally joined AMR in 1985, had two terms as CFO (broken by a four–year stint as CFO and vice–chairman of AT&T in 2002–2006) and was named president in 2010.

As a nice touch, Arpey has joined Emerald Creek Group, the private equity firm founded by another highly–regarded former airline leader, ex–Continental CEO Larry Kellner. As partner, Arpey will lead the Houston–based firm along with Kellner.

A week after the filing AMR announced more top management changes. With the retirement of three senior executives, the leadership team was streamlined and reduced in size. Also, AMR named its treasurer Beverley Goulet chief restructuring officer (CRO).

What kind of Chapter 11?

AMR’s filing, in the federal bankruptcy court in the Southern District of New York, listed total assets of $24.7bn, total debts of $29.6bn and cash of $4.1bn.

As is typical in airline bankruptcies, general shareholders are unlikely to see any recovery in their investment. The old stock becomes worthless and is typically wiped out when the company exits Chapter 11 (and issues new shares).

Secured creditors can expect to recover close to 100% of their claims. AMR’s court documents listed a substantial $10bn of secured debt. According to JP Morgan, that includes $2.1bn in EETCs, $1.7bn in other secured bonds, $1.6bn in special facility revenue bonds, $3.9bn in other types of secured debt and $694m in capital leases.

Unsecured creditors as a group typically recover only a fraction of their claims. Fitch Ratings estimated that holders of AMR’s unsecured notes and debentures, which total around $845m, will likely recover 10% or less of face value.

AMR’s largest trade creditors include Boeing, Rolls–Royce, Hewlett–Packard, Sky Chefs, Honeywell, CITGO Petroleum and various airport operators. The most fortunate are those designated as “critical vendors”. AMR immediately sought court approval to pay $50m of the $85m claims submitted by select vendors – a group that include providers of in–flight training, aircraft parts, “essential” amenities, ground services and information technology. The other trade creditors will have to wait until secured creditors have been paid and until AMR decides which aircraft, goods, services, facilities and contracts it wishes to keep, reject or renegotiate.

The nine–member official committee of unsecured creditors includes AMR’s three key unions – Allied Pilots Association (APA), TWU and AFA. This unusually high level of union representation reflects the fact that revising labour contracts will be the key component of AMR’s restructuring. The committee also includes three financial institutions (Wilmington Trust, Manufacturers and Traders Trust and Bank of New York Mellon) Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp or PBGC (which could become a major creditor if AMR terminates its pension plans), Hewlett–Packard and Boeing Capital.

The unsecured creditors committee has a say in major decisions outside of normal business in Chapter 11, including shrinkage, mergers and pension plan terminations. In Delta’s bankruptcy US Airways’ hostile bid failed essentially because the unsecured creditors committee refused to support it.

In some respects at least, the restructuring looks relatively straightforward. The $4.1bn cash reserves will keep the airline running normally and make it unnecessary to obtain DIP financing.

There was a sense of inevitability about AMR’s Chapter 11 filing – something that just may pave the way for a smoother restructuring process. There is also a consensus that the restructuring will be successful, just like the other recent US legacy Chapter 11s. AMR will also benefit from the lessons and experience of the other carriers.

AMR is expected to spend 18–24 months in Chapter 11, roughly the same as Delta and Northwest (20–21 months) but much less than UAL (three years). However, AMR’s aim is to be out of Chapter 11 within 18 months (or at least submit its reorganisation plan in that timeframe), because under new bankruptcy rules passed in late 2005, outside parties can submit rival reorganisation plans after 18 months.

Bankruptcy lawyers have commented that it is quite possible for AMR to get it done in 18 months, but not being able to reach consensual agreement with various stakeholders could prolong the process. Section 1113 (rejection of collective bargaining agreements) and Section 1114 (modification of retiree benefits) are also arduous processes that could drag on.

Of course, regardless of how difficult and contentious the restructuring gets, it will be “business as usual” in airline operations. There will be no effect on oneworld or other code–share operations.

Implications for labour

It is not clear if American’s union leaders were caught totally by surprise by the Chapter 11 filing decision and it hardly matters now. But the fact is that Chapter 11 will mean deeper labour concessions than the ones unions have been turning down in negotiations. Last month APA’s leadership refused to consider proposals that reportedly involved 7–9% salary increases in return for longer working hours and reduced pension contributions. (After the Chapter 11 filing one APA official was quoted being rather philosophical about it; he noted that sometimes it is easier to have things imposed on you.)

AMR has not released specific cost cutting targets but has said publicly that its annual labour costs are $800m higher than those of its large competitors. The labour cost disadvantage relates particularly to work rules, productivity and benefits, rather than pay scales. The key issue with the pilots is relaxing the uncompetitive scope clause to permit more large RJs and allowing more domestic code–sharing. Under the current contract, AMR is limited to just 46 70–seat aircraft, when Delta and UAL can operate three to four times as many 70–90 seaters.

Even in Chapter 11 the preference is to reach consensual labour agreements. So, AMR will sit down with its union leaders and non–organised work groups and negotiate under the supervision of the court. But if consensual agreement is not reached in a timely manner, AMR can ask the court to terminate the contracts, after which wages and work rules would be set under federal labour laws. That would be a disastrous scenario from the morale viewpoint, making it tougher or even impossible to repair labour relations after bankruptcy.

There is always hope for innovative approaches. It has been suggested that the pilots could look for a future ownership stake in AMR in return for concessions – one possible reason why they want help from Wall Street restructuring experts.

The fate of AMR’s defined–benefit pension plans is potentially the most controversial part of its reorganisation. According to PBGC (the US agency created to protect private retirement benefits), American sponsors four traditional pension plans with $8.3bn in assets to cover $18.5bn in benefit obligations for 130,000participants. If the airline were to terminate the plans, PBGC would pay out about $17.5bn and about $1bn in benefits would be lost (because PBGC’s payments are capped under federal law). Furthermore, a default by AMR would significantly worsen the agency’s financial position; it already has a $26bn deficit and needs to sharply increase premiums to cover that. (PBGC does not receive taxpayer funds; its operations are financed by insurance premiums paid by companies that have defined–benefit plans and with assets and recoveries from failed plans.)

AMR has not yet decided what to do with the pension plans or filed any pension–related documents in court. But the leadership has stated that pensions are a very big part of AMR’s cost disadvantage. Also, AMR’s lawyers have been saying publicly that the airline cannot sustain the current plans and must switch to defined–contribution plans.

PBGC has responded swiftly with a series of strongly–worded statements from its director, Josh Gotbaum. First, the agency has said that it will work with AMR, as it does with other companies, to “encourage American to fix its financial problems and still keep its pension plans”. Second, Gotbaum has said that before AMR could back out of its retirement commitments, it would “have to prove it can’t successfully reorganise if the pensions continue”. PBGC is a “pension safety net, not a convenient option for companies that want to sidestep their retirement commitments”.

Many companies in Chapter 11 do keep their pension plans or terminate only some of them. While UAL and US Airways shed all their traditional plans in bankruptcy (UAL had a funding gap similar to AMR’s), Northwest did not terminate any plans. Delta terminated the plan covering its unionised pilots but maintained other workers’ plans, though it no longer makes contributions.

AMR has kept up with its immediate pension funding commitments. It met its estimated 2011 minimum required contribution of $520m by September and expected to pay $560m in 2012 (these amounts benefit from pension relief measures introduced by legislation in 2006 and 2010). But AMR’s unions will use that to argue why the pension plans should be maintained.

Morale at AMR will be weakened also by layoffs, necessary as the airline shrinks. Given that termination of all four pension plans would be disastrous for employee relations, hopefully there will be some kind of a compromise solution (perhaps somewhere between the UAL and Delta outcomes).

Of course, AMR’s bankruptcy was a major blow also to other large US airlines’ unions (particularly at UAL and Delta),many of which were targeting American’s industry–leading pay rates in their current contract negotiations.

Expected fleet strategy

AMR is committed to modernising its aging fleet, so its fleet strategy in Chapter 11 is simple: keep all the new aircraft orders and accelerate older aircraft retirements. This strategy is an important part of gaining a competitive cost structure.

So, the $40bn of orders that American announced in July for 460 Airbus and Boeing narrowbody aircraft, which secured $13bn of attractive lease financing, would appear to be safe, with one exception: the order for 100 737 MAX aircraft, which was not yet firm. Airlines in Chapter 11 are normally allowed to keep firm orders, but it is hard to persuade the court to authorise new obligations. AMR may have to wait until it exits Chapter 11 to confirm the MAX order.

This may not affect AMR much at all. Boeing, which was fortunate to clinch a massive firm 737 MAX order from Southwest earlier this month (making Southwest the type’s launch customer), has said that it will keep aircraft available for AMR (like it has done in the past). The MAX is not available until 2017 anyway, and American has plenty of 737NGs joining the fleet in the coming years (including 100 new firm 737NG orders placed in July). As to aircraft retirements, the main focus will be to rapidly downsize the fleet of MD80s, which still total over 200 or almost a quarter of AMR’s fleet. Fortunately, many of the older MD–80s are on operating leases, which can be easily rejected in bankruptcy. The first batch of such rejections (20 MD80s and four Fokker 28s) took place within a day of the Chapter 11 filing.

S&P suggested that, in addition to MD- 80s, AMR is likely to retire more 757s, 767s and small regional jets – mostly domestic service aircraft. The extent would depend on how AMR wants to change its network and capacity, which in turn could depend on the extent of the scope clause relaxation. But the sheer size of the old fleet means that AMR cannot immediately retire all of the aircraft even if it wanted to.

AMR is now conducting a “tail–by–tail” review of its fleet, to see which aircraft it wishes to keep, reject or renegotiate. The airline noted in court filings that the market values and market lease rates of many of its aircraft have changed substantially since the aircraft were originally leased or financed.

The process can get complicated with debt because not all aircraft are financed individually and many EETCs have cross–collateralisation and cross–default provisions. For example, suspending payments on one aircraft may risk certificate–holders foreclosing on all the aircraft in that series. So AMR may end up having to keep some aircraft that it did not want to keep.

AMR’s shrinkage and industry impact

Most analysts believe that AMR will see ASM shrinkage in the region of 10% in bankruptcy. This seems more than the “modest reduction in flying” Horton initially talked about, but it would be less than the 15–20% cuts Delta, Northwest and UAL implemented in bankruptcy.

Horton has signalled a firm commitment to the “cornerstone” strategy, in which 98% of AMR’s flights begin or end in five major US cities: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas and Miami. But many analysts argue that the strategy has been successful only in Miami and Dallas, where AMR has dominant market shares. Los Angeles, in particular, is seen as ripe for cutbacks on less profitable flying. Some analysts also call for cuts at Chicago, the hub that AMR shares with UAL.

American will probably not want to reduce service in the business travel dominated markets across the Atlantic and the Pacific, but some analysts have suggested that it may consider reversing some of its recent expansion to secondary European cities and to Tokyo. American can be expected to continue downsizing its presence in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean.

Should American wish to reduce transatlantic and transpacific flying, now at least it has greater flexibility to do that thanks to the immunised JVs with IAG and JAL. BofA Merrill Lynch’s Europe–based analysts suggested that the IAG/AA JV could see some “trimming of non–core lower profitability routes”.

As has been observed in previous legacy bankruptcies, AMR’s contraction should have positive impact on the rest of the US airline industry. First, the capacity cuts will lead to a better domestic pricing environment, boosting revenues. Second, UAL and Delta could gain corporate market share because of the uncertainty surrounding AMR. Third, relaxation of domestic code–sharing limits at AMR could lead to new connecting opportunities for JetBlue in the East and Alaska in the West. Fourth, relaxation of AMR’s scope clause could lead to new opportunities for regional carriers. Fifth, with AMR’s labour costs coming down, there is less wage pressure at other carriers (particularly benefiting UAL). Sixth, the AMR reorganisation could be a catalyst for further industry consolidation, which would further reduce capacity.

JP Morgan estimates that a 10% capacity reduction at AMR would divert 6% or $1.4bn revenue to competitors. This equates to a 1–3% revenue improvement per competitor in 2012. The impact would be to measurably boost other US airlines’ profits next year. Airline stocks have also benefited. JP Morgan analysts noted on December 13: “There is little question that AMR’s bankruptcy has served as a catalyst in significantly rekindling investor interest in the space”.

BofA Merrill Lynch analysts estimated that as a result of AMR’s capacity cuts (which they assumed would be 5%) the industry may need only 2.5% revenue growth to double earnings in 2012. In their view, absent a recession and a further spike in oil, some airline stocks have the potential to double over the next 12 months.

Horton’s very bullish statements about AMR’s longer–term potential and desire to “grow and prosper” gave the impression that, once it has closed the cost gap, AMR could leap to the top of the profit league and start behaving quite aggressively. JP Morgan analysts disputed any such suggestions, saying that no airline had emerged from Chapter 11 on the offensive and that “AMR is at best expected to emerge with cost parity, not superiority”. In their prediction, AMR would have operating margins superior to those of US Airways but falling short of Delta’s, Southwest’s and UAL’s (see chart, below). S&P described the post–bankruptcy AMR as a “somewhat smaller airline with more competitive labour costs and a lighter debt load”.

There is considerable disagreement in the financial community about the odds of AMR being involved in a merger in the next couple of years. Proponents have argued, first, that history suggests there will be a merger. Second, bankruptcy makes AMR vulnerable to unsolicited takeover bids from rival carriers. Third, many believe that US Airways will make such an unsolicited bid; after all, it made a run for Delta, talked with UAL about a merger and continues to be a strong proponent of consolidation. Fourth, AMR may need increased scale to compete equally with Delta and UAL for corporate contracts. Fitch Ratings went as far as to say that AMR “may ultimately face the need to consider a merger with US Airways as the only path to strategic relevance in an industry where global network scale and scope is more important than ever”.

But many others find it hard to see what AMR would gain from a merger with USAirways. S&P highlighted two major negatives. First, US Airways’ route network, which focuses on leisure destinations or second–tier business markets and faces significant competition from Southwest, would not fit into American’s current business strategy, which focuses on major business markets in the US and building closer ties with airline partners overseas. Second, there are the labour issues. US Airways has still not fully integrated its employee groups from the 2005 merger with America West; the pilot groups cannot agree on seniority list integration. Clearly, combining that with AMR’s very difficult labour relations could be a recipe for disaster.

Many analysts have echoed those sentiments, some even suggesting that they would see more sense in a Delta–US Airways or UAL–US Airways combination. Others have made the point that consolidation can take different forms. AMR’s strategy of forging immunised global joint ventures will certainly help it gain scale and scope. It will be the perfect candidate for an international merger (with IAG) when such deals become possible. Then again, as S&P pointed out, AMR may have less control over whether it merges, particularly if its reorganisation takes longer than 18 months.