Gol: Multiple code-shares, no global alliance for Brazilian LCC

December 2010

Gol Linhas Aereas Inteligentes, Latin America’s leading LCC, has returned to healthy profitability, having put the Varig problems behind it and thanks to strong demand growth in the Brazilian market. But new challenges loom on the horizon, including a TAM/LAN combine that will dominate Latin America (see Aviation Strategy briefing, September 2010). What strategies will Gol deploy to ensure success in a changing competitive landscape?

In the past two years, following the near disastrous April 2007 acquisition of Varig, Gol has focused on “getting back to basics” of being an LCC, rebuilding profit margins and repairing the balance sheet, while capitalising on the competitive strengths gained through the merger.

Those efforts have been highly successful. Gol’s ex–fuel unit costs are almost back to the pre–Varig levels. Liquidity has improved dramatically: cash reserves amounted to a very healthy 26% of annual revenues in September, up from just 11% a year earlier. Gol has also made headway in de–leveraging its balance sheet.

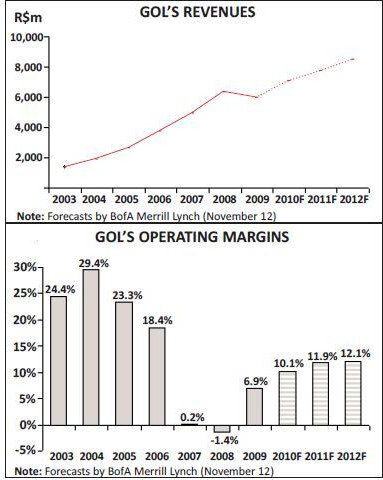

Gol’s revenues have surged in the past 18 months, thanks to strong demand growth fuelled by Brazil’s booming economy and fierce price competition among airlines. Brazil escaped the global recession relatively lightly. Domestic RPK growth picked up sharply in mid–2009, after a brief dip earlier in the year, and amounted to 17.7% in 2009, followed by 24.3% in January–November this year.

As a result of the cost reductions and the strong upturn in demand, Gol’s operating margins have risen steadily and are expected to pass the 10%-mark this year for the first time since 2006.

In the past two months’ round of annual investor meetings, which have included “Gol Days” in New York, London and Sao Paulo, the management has been selling Gol as a “consistent” (or safe) investment case. The executives reaffirmed that Gol’s long–term strategy is to continue being the “lowest cost airline in Latin America”, that Gol is going for profitability rather than market share and that it aims for sustainable growth with a “prudent but adequate” fleet plan.

Gol’s main focus is to “take advantage of the new middle class opportunity in Brazil”. Brazil is one of the most attractive aviation markets in the world today because of its size and growth potential. Only 17m people currently fly in a population of 190m. Those 17m people represent around 60m passengers annually – a number that Gol’s executives believe could double, triple or even quadruple in the next 5–10 years. The segment with the greatest potential is the new middle class, which has grown from 76m people in 2003 to 98m in 2009 and is projected to expand to 130m.

Gol is well positioned to tap the growth opportunities in Brazil because of its competitive advantages, including leading position in many key markets, formidable slot holdings at the main airports, cost leadership, standardised fleet of 737NGs, largest e–commerce platform in Latin America and a strong loyalty programme.

Adding it all up, most analysts consider Gol’s future very bright and foresee steadily improving operating margins. However, there are some concerns.

First, analysts particularly in the US are keeping a close eye on the yield environment in Brazil. 2009 saw damaging price wars, triggered by the arrival of Azul and the growth of other small upstarts such as Webjet and TRIP. The fear is that price wars could re–emerge as significant industry capacity addition continues and the new entrants enter more markets.

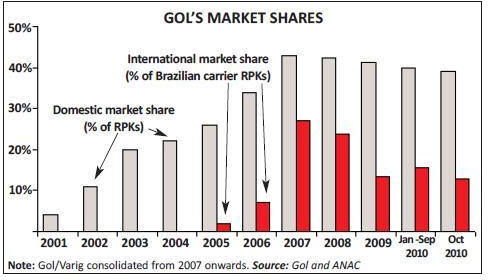

Second, there are concerns about the potential impact on Gol of the planned TAM/LAN merger, which would create a dominant player in Latin America and a stronger competitor in Brazil. Will Gol lose market share? How would it respond?

Third, Gol and TAM are seeing a steady erosion of domestic market share as the new entrants expand. Could the current Gol–TAM duopoly eventually give way to a regime of three or more sizeable competitors?

Double-digit margins return

Fourth, will the infrastructure be there to accommodate the demand growth? Although hopes high that the major international sports events secured by Brazil — the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016 — will ensure much–needed investment in airports, the plans announced so far are far from adequate. Gol has had three distinct chapters in its 10–year history. Up to and including 2006, it was one of the world’s most profitable and rapidly growing airlines. It achieved annual operating margins in the 19–29% range and net margins in the 13–20% range in 2003- 2006, while its ASMs almost tripled. The airline went public in 2004, listing its preferred shares in Sao Paulo and New York (though its founders, the Constantino family, still hold 64.4% of the total stock).

Gol then had two years of break–even results or losses in 2007–2008. The good times ended in late 2006, when the Brazilian airline industry faced an ATC/infrastructure crisis that lasted through the first quarter of 2008. The situation was aggravated by two fatal crashes (a Gol 737 in September 2006 and a TAM A320 in 2007), which led to further ATC and airport restrictions.

In the middle of that turbulence, Gol acquired bankrupt Varig. The R$562m acquisition turned out to be very problematic, partly because of the delay in getting government approval to combine the two companies. Gol was not able to integrate the networks until October 2008. With losses mounting, in 2008 Gol also had to shut down Varig’s remaining long–haul operation in favour of focusing on serving markets within South America.

In its third chapter which began in 2009, Gol has staged a financial recovery. It accomplished that after finally being able to reap synergies from the Varig acquisition and getting its costs in line.

Gol’s results are best examined on an operating basis, because its net results have fluctuated wildly due to currency movements. In 2008 it reported a massive R$1.2bn net loss (19.3% of revenues) because of the sharp deterioration of the Brazilian Real against the US dollar after the start of the global financial crisis, which resulted in steep foreign exchange losses on Gol’s dollar–denominated debt. The situation was reversed in 2009, when the Real recovered by 34%, producing a R$711m non–cash gain that boosted Gol’s net profit to R$891m (14.8% of revenues).

After achieving a modest 6.9% operating margin in 2009, Gol has consolidated its financial recovery this year. In the third quarter, its revenues soared by 19.5% and it earned a R$187.2m (US$107m) operating profit, accounting for 10.5% of revenues – its highest quarterly margin since the Varig acquisition.

It has been a demand–led recovery. Gol’s total RPKs rose by 23.3% in the third quarter, which was attributed to economic recovery and factors such as “dynamic fare management” (discounting to attract the emerging middle classes). Nevertheless, overall yields stabilised, reflecting a more rational competitive environment and higher volumes of business traffic.

Gol’s unit revenues rose by 5.3%, while unit costs were essentially flat. The 1.3% reduction in ex–fuel CASK was driven by capacity growth, reduction in the number of grounded aircraft, higher aircraft utilisation, lower leasing costs and a stronger Real. Leasing costs fell because this year Gol has returned all 11 of its leased 737–300s as part of its fleet standardisation.

Significantly, Gol has finally shed or found profitable uses for all of the 14 767–300s that came with Varig. Having long been stuck with the remaining five 767s, which were grounded and cost a fortune in lease payments, Gol has subleased out one and introduced the other four to charter operations. The latter was possible because of the recovery of the international charter market. Reactivating the 767s required some investment, but it was still “cheaper to have the 767s flying than sending them back to the lessors”. The intention is to return the air–craft when their leases expire in 2012–2014.

A key part of the “back to basics” strategy has been to restore aircraft utilisation towards pre–Varig levels. Gol is now at around the 13 hours per day mark, up from 11–12 hours in 2008, but believes that it can get close to 14 hours.

The business model

Gol has maintained a cost advantage over TAM and other Latin American peers. According to the Gol Day presentation, its total cost per passenger of US$117.5 in 2Q10 was 42% lower than its Latin American peers’ and 37% lower than TAM’s. Its CASK in the 12 months to June 30 was 36% below Latin American peers’. Gol’s post–Varig business model is an interesting mixture of LCC economics and multi–brand operations. In the US or Europe, such a business model might be seen as too confusing and complicated for an LCC, but it is probably ideally suited to the Brazilian market.

Gol has always catered for both the leisure and business segments. Its original raison d'être was to stimulate leisure traffic, to get Brazilians to switch from long–distance buses to travel by air. When it started, only 5–7m Brazilians were flying, compared to 17m today. Gol pioneered low fares in Brazil and has had tremendous positive social impact. But, because business travel accounts for some 70% of the local market, Gol has always also carried significant volumes of business traffic.

The acquisition of Varig, Brazil’s former flag carrier and one of the oldest brands in Latin America, provided an opportunity for Gol to strengthen its offering to the business segment and gain high–yield market share on intra–Latin America international routes. But Gol’s main focus continues to be to stimulate leisure travel by the emerging C and D classes in Brazil, because that is where the pent–up demand is.

While integrating the two companies and introducing a unified 737–700/800 fleet, Gol has maintained two airline brands. Varig offers a business class, while Gol remains single–class. Varig’s role is to operate medium–haul international service to major destinations in South America, while Gol focuses on domestic service and short–haul international routes.

Thanks to Varig, Gol has significantly strengthened its position at Sao Paulo’s Congonhas, Brazil’s most important business hub, as well as other key airports, enabling it to offer a more consistent, high–frequency service in the main domestic business markets.

Much effort has gone into developing the Smiles FFP, which now has over 7m members and 180 commercial partners. Gol already offers a co–branded credit card and has raised funds from the programme through an advance sale of miles. A desire to generate more value for Smiles members was one of the key reasons why Gol began to forge code–share partnerships with global carriers in 2009.

To stimulate leisure travel, Gol has come up with imaginative programmes such as VoeFacil (“Fly Easy”), which lets its customers finance their tickets in up to 36 monthly payments at a relatively low interest rate. VoeFacil stores have been opened at locations such as bus stations in high–density middle class areas.

So Gol is now better able to explore all segments of the air travel market. Its offerings have expanded to five brands: Gol, Varig, Smiles, VoeFacil and Gollog (cargo subsidiary).

Balance sheet strengthening

The latest focus is growing ancillary revenues. Items such as cargo, flight rebooking and excess baggage fees and on board sales currently account for 11% of Gol’s total revenues – about the same as at JetBlue but much less than the 22–28% shares at Allegiant and European LCCs. Gol hopes to boost the ancillary percentage to 14% in 3–5 years (bearing in mind that passenger revenues are growing too). The projects include buy–on board service, a “cost–effective” type of wireless in–flight entertainment service and developing the E–commerce platform (which handles 93% of Gol’s ticket sales) to facilitate sales of insurance/hotel/other bundles. Gol is also striving to grow its cargo revenues from 4% to 5% of total revenues; plans include express cargo products. The Varig acquisition brought Gol close to a liquidity crunch in early 2009: its cash reserves amounted to only 5% of annual revenues in March 2009. Although Gol was subsequently able to quickly raise funds from a variety of sources to dramatically improve its liquidity, it seems that the experience prompted it to adopt much more conservative spending and balance sheet management policies.

To start with, Gol now has a minimum cash target of 25% of annual revenues. CFO Leonardo Pereira said recently that the ideal range is currently considered to be 25–30%.

Last year’s cash–raising included, first of all, Gol’s controlling shareholders providing R$204m through a rights offering. The airline then issued R$400m of two–year debentures and raised R$255m through the advance sale of frequent–flyer miles to two local banks. And, amazingly, in October 2009 Gol was able to complete a major global share offering that boosted cash by R$627m.

As a result, Gol’s cash reserves surged to R$1.44bn (US$735m) by year–end 2009 – a very healthy 24% of annual revenues. The latest (September 30) balance – R$1.77bn or 26.3% of trailing 12–month revenues — exceeded the 25% target set for 2010.

Gol also plans to de–leverage its balance sheet in the future. This year’s focus has been to reduce near–term debt obligations through refinancings. Total debt has increased (R$3.6bn on September 30, up 18% on the year–earlier level), but there is now no major debt maturing before 2014. If cash levels continue to build and cash flow remains strong, the airline will start paying down debt.

Gol has a target of reducing its adjusted gross debt to less than 4.5 times EBITDAR in the next two years. The leverage ratio in 3Q10 was 5.6 times, down from 6.6 in 3Q09 and 14.2 two years ago.

The strengthening balance sheet is already paying dividends in terms of improved credit ratings and reduced cost of borrowing. This year the three main rating agencies have upgraded Gol’s credit ratings to the “BB” brackets. The airline is committed to keeping those ratings and has no plans to issue new debt. Of course, Gol wants strong cash reserves and reduced leverage so that it has more flexibility and can make the most of the growth opportunities available in Brazil.

Conservative fleet plan

BofA Merrill Lynch analysts suggested in a recent report that, given Gol’s leverage discipline and liquidity focus, the airline might access the equity capital markets to finance fleet growth before 2013. With the departure of the 737–300s, and except for the four 767s in charter operations, Gol has now completed the standardisation of its fleet around the 737- 800NGs and 737–700NGs, resulting in significant cost savings. Its year–end fleet for the two types will total 111, of which 71 are 800s and 40 are 700s.

Gol is maintaining its original fleet plan, which will see 14 more 737–800s delivered in the next four years, to bring the total 700/800 fleet to 125 by the end of 2014. However, the airline recently placed a new order for up to 30 737–800s (20 firm and 10 options) for delivery in 2014–2017. This will help reduce the average fleet age to below six years.

The fleet plan seems conservative for an LCC that has access to a promising growth market. But Gol is determined to maintain capacity in line with demand; in the summer the management were talking about wanting to add capacity roughly at the rate of two–thirds of demand growth. Also, the fleet plan assumes that Gol will get more ASMs through increased utilisation and a larger average aircraft size (the 737–800s have more seats).

Gol’s CFO commented in the carrier’s 3Q call that it is relatively easier to bring aircraft in than dispose of them. “We’d rather bring aircraft in on an operating lease basis, if needed, than make a commitment at this stage for something that could jeopardise the company’s financial results in the long run.”

Alliance considerations

Gol has no interest in adding a second smaller aircraft type to the fleet. As CEO Constantino Junior has said: “Considering our model, where we want to be in a few years’ time and infrastructure issues, we think at this stage the right plane for us is the 737–800”. Gol’s network currently covers 53 destinations in Brazil – connecting all the important cities – and 14 major destinations in South America and the Caribbean. Although the best growth opportunities are in the domestic market, the airline is likely to continue to expand to other South American countries as the other economies become stronger.

In fact, much of the new activity recently has been in the international arena. Gol began regular service to the Caribbean in 2009 (under the Varig brand) and this year has added three new destinations there – Barbados, St. Maarten and Punta Cana (Dominican Republic). Gol has also recently boosted flights to Argentina. These services have benefited from a strengthening Real, which has boosted Brazilians’ international travel.

But Gol no longer has any plans to enter long–haul international markets. This and the acquisition of Smiles FFP, which has enabled it to do reciprocal deals with other carriers, led to a change in the way Gol viewed alliances. After previously shunning them, in the past 12 months Gol has forged a large number of code–share deals with global carriers. It has been able to link with both SkyTeam and oneworld carriers. It has agreements with American and Delta, which between them account for more than 50% of total Brazil–US traffic, and with AF–KLM and Iberia, which both have high shares of Europe–Brazil traffic. It also code–shares with Aeromexico, which has 85% of Brazil–Mexico traffic.

This strategy of forging multiple code–shares is similar to what JetBlue and WestJet are doing, except that Gol has moved a lot faster and is focusing only on the most important airlines in the long–haul segment.

Gol’s leadership has said on many occasions recently that they do not see benefit in joining a global alliance. CEO Constantino Junior made the point at Gol Day that his airline does not need support from a global alliance at foreign destinations, because it does not fly long–haul. “So that creates a very interesting situation where we can position ourselves as a distributor for these alliances without any conflict.”

Gol is looking to sign more code–shares in the future, in particular with airlines in Asia and the Middle East. Gol also plans to upgrade its reservations technology to permit truly reciprocal code–sharing arrangements with its foreign partners.

On the domestic front, in September Gol entered into a commercial agreement with NOAR Linhas Aereas, a tiny Recife–based turboprop start–up. The management has since indicated that they are open to similar code–shares with other small carriers in niche markets.

The multiple code–share alliances with foreign partners will help cushion any adverse impact on Gol of the TAM/LAN combination. The alliances should also help Gol reap benefits from the traffic growth that the future US–Brazil and EU–Brazil open skies regimes will bring.

As to the potential TAM/LAN impact, Gol is expected to gain in the short term as its competitors face a challenging merger integration period. In the longer term, Gol believes that it will maintain its competitive advantage because of its low cost structure and domestic focus. Its business model is very different. Also, Gol’s management regard LAN as a very rational, profit–focused competitor.

Longer-term outlook

While Gol will obviously look at any merger or acquisition opportunities that may present themselves, its executives believe that the business model is sustainable on a standalone basis. According to the CFO, the company’s actions in the next two years will be guided by two “anchors”. First, there is a clear mandate from the shareholders that the low–cost model must be preserved. Second, the shareholders want to be in this business in the long run, so Gol must not take risks that would put its survival in jeopardy. Gol is projecting a 10–13% operating margin for 2010 and aims to improve it steadily in the next three years towards a goal of 15- 18%. GDP and demand projections certainly support strong earnings growth in 2011. Realistically, however, price wars could limit Gol’s margin expansion, as well as keep its stock under pressure.

Analysts regularly voice concerns about the competitive environment in Brazil. A recent research note on Gol from JP Morgan pondered that the “cost competitiveness and growth of Azul remains troublesome”, particularly when compared to the reasonably tame discounter trends in North America.

However, some of those developments are less alarming when considering the special circumstances in Brazil. First, the domestic market is so large and dynamic that there is probably enough traffic for everyone. Second, it is an untapped market that needs to be stimulated, so the airlines need to be able to offer low fares. Profit margin improvements will not come from higher yields but, rather, from higher traffic volumes and load factors. Third, slot constraints at the main airports will limit smaller competitors. With Gol and TAM controlling most of the slots, it would be tough for any newcomer to achieve competitive advantage. Fourth, many of the new entrants are aiming for different markets and do not really overlap with Gol; they use smaller aircraft and operate to smaller airports. Fifth, many of the new entrants in Brazil today have professional managements and focus on providing returns to investors; Azul is believed to be planning an IPO in 2011.

Perhaps the biggest concern is whether the aviation infrastructure will be there to support the demand growth. According to Gol, the Brazilian government has committed to spending R$6bn on airport facilities to accommodate growth through 2014–2015. But the problem is that if GDP and traffic growth continue at rates the airlines are predicting, airport capacity limits may be reached even before the 2014 World Cup.