Gulf LCCs search for niches

December 2009

Following the success of Air Arabia, the Gulf region has seen a steady wave of LCC launches, including flydubai, Jazeera Airways, Nas Air and Sama Airlines. But can these airlines carve out a niche against the extensive regional networks of the Gulf-based full service airlines?

After Air Arabia was launched in October 2003 (see Aviation Strategy, April 2009), a number of LCCs have emerged across the region, aiming to take advantage of the increasing number of “open skies” signed between Gulf states and other countries, the abundance of airport capacity, the ready availability of capital (even in the teeth of recession) as well as the geographic and demographic advantages that the region enjoys.

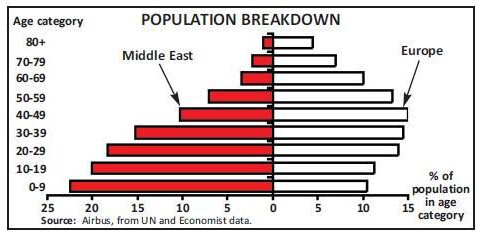

At first sight, the business case for LCCs looks persuasive. In its recently–released forecast for 2009–2028, Airbus says that “several indicators in the Middle Eastern region show that the domestic market is about to boom”. Key among these is the region’s demographics, with 60% of the Middle East’s population being less than 30 years old, compared with 35% in Europe (see chart, below). Undoubtedly this population will provide a steady stream of new customers for LCCs over the coming decades.

On top of that, the Gulf’s geographical position gives it easy access to huge populations in other countries. Approximately 36% of the world’s population and 16% of global GDP is located within 2,500nm (4,630km) of the Middle East, according to Airbus, and these figures rise to 86% and 63% respectively within a distance of 4,500nm (8,340 km).

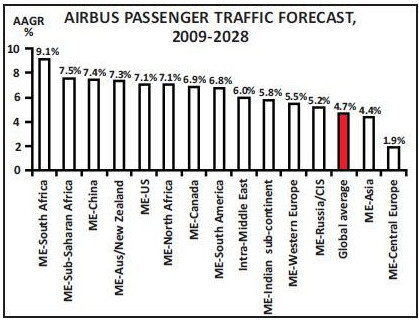

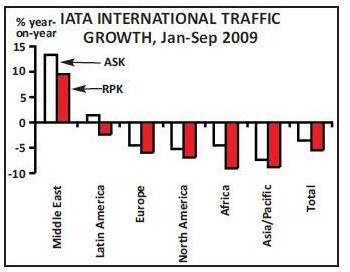

While the rest of the world has been going through an aviation downturn, the Middle East is the only region that has actually seen demand grow this year – by a huge 9.4% in the January–September period (see chart, below). Additionally, Airbus forecasts that almost all Middle Eastern aviation markets will beat average global growth rates over the next 20 years (see chart, below).

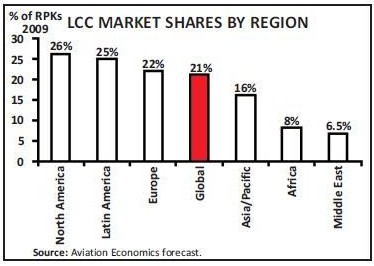

Despite all this, the penetration of LCCs into the Middle East region has been relatively slow. Even after the slug of new launches, the LCC share of the Middle Eastern market is barely touching 7%, according to Aviation Economics’ analysis, and it is well behind the penetration of LCCs in all other markets in the world (see chart, below).

This year has been particularly difficult for the LCCs, as the big network carriers in the Gulf region have shifted resources and attention closer to home, thanks to weaker business–class demand for long–haul flights. With some of the wave of LCCs that followed Air Arabia finding it difficult to break into profit, the rise of the LCCs in the Middle East appears to be more of a struggle than many had previously predicted.

Added to this is the current financial crisis in Dubai, which must be affecting business and consumer confidence in the wider Gulf region — although thanks to their fares the LCCs should suffer far less than the network carriers if the crisis deepens.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Arabia | |||

| A320 | 16 | 48 | 5 |

| flydubai | |||

| 737-800 | 5 | 49 | |

| Jazeera Airways | |||

| A320 | 10 | 30 | 4 |

| Nas Air | |||

| A319 | 20 | ||

| A320 | 7 | ||

| E-190 | 4 | 9 | |

| Sama Airlines | |||

| 737-300 | 6 | ||

| BAe Jetstream 41 | 1 | ||

| Total | 49 | 156 | 9 |

flydubai

Set up in March 2008 with AED250m (US$67m) of start–up capital from the Dubai government, the Dubai–based LCC was “officially supported” during its launch by Emirates Airlines, although it operates independently from its so–called sister company. Its CEO is Ghaith Al Ghaith, previously an EVP at Emirates Airline, but the airline has plenty of LCC experience, with CFO Neil Mills formerly at easyJet for 12 years, while COO Kenneth Gile was previously president of US LCC Skybus Airlines and chief pilot at Southwest.

flydubai placed an order for 50 737–800s — some of which can be upgraded to the 737- 900ER variant — at the Farnborough Air Show in July 2008 (worth $4bn at list prices, though costing flydubai considerably less than this). The airline started operations in June this year out of the revamped Terminal 2 at Dubai International airport with a route to Beirut, and it has grown steadily since.

The fifth aircraft of its Boeing order was delivered in October 2009, being put into service on a new route to Doha launched the same month, while in November routes were launched to Baku in Azerbaijan and to Khartoum in the Sudan. At 2,600km Khartoum is the longest sector yet in flydubai’s network, which now comprises 10 destinations including Beirut, Amman, Damascus, Aleppo (in Syria), Alexandria and Djibouti.

A sixth aircraft will be delivered before the end of this year, and four of flydubai’s first six aircraft have been sold to and leased back from GECAS in a financing deal for aircraft worth $320m at list prices, although financing for the other aircraft (being delivered up to 2015) is yet to be announced. The 737–800s are configured in a high–density 189–seat layout, and flydubai has a typical LCC business model, with passengers paying extra for checked–in baggage, seat selection, extra leg–room and on–board catering. Interestingly, as well as selling tickets online and via call centres, flydubai sells through the 100 outlets of the Emirates Post Office, which are linked directly to flydubai’s reservations system.

While the initial focus was largely on the Middle East, flydubai also wanted to launch routes to India – to Lucknow and Chandigarh in the north and Coimbatore in the south – in July. However these plans had to be suspended due to “operational issues”, thought to be a refusal by the Indian government to give permission for the routes due to concerns about the competitive impact on Air India Express, the LCC of flag carrier Air India. A reluctance to open up markets is holding back LCCs, says Al Ghaith, and he is lobbying hard for open skies in all markets. Al Ghaith is also concerned about visa requirements in Middle Eastern and Gulf states.

flydubai is looking to add routes to destinations within 4.5 hours flying time from Dubai, which the airline estimates encompasses 2bn people, and in the medium–term flydubai plans to extend its network to eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union countries and North and East Africa. It’s greatly helped in this by its Dubai emirate owners, and indeed the UAE has been including flydubai as a designated airline in its latest “open skies” ASAs signed with Bulgaria and Estonia in July and Zambia in October.

Operational data is scarce, but Al Ghaith says that load factor has been “better than expected” and that the pace of expansion will increase in 2010 and again in 2011, claiming that the global recession has not had any impact on flydubai’s plans. Indeed the airline is considering strengthening its fleet still further, with new orders likely to be placed sometime in 2010. However, these plans may well be affected by the current Dubai financial crisis, which may choke off new cash injections by the Dubai state. On the other hand, the crisis may encourage passengers to try or switch to LCCs like flydubai, so ironically the troubles at the Dubai state may turn out to be beneficial.

Neverthless, the airline’s ambition is understandable since flydubai is part of the Dubai emirate’s larger plan to attract 15m annual visitors to the state by 2015. As well as tourists and business executives the LCC should prove immensely popular with the huge VFR market to/from Dubai, and specifically the hundreds of thousands of workers from the Middle East, Africa and Indian subcontinent who work in Dubai and neighbouring emirates at close to poverty wages, and for whom cheap air fares are of huge benefit.

LCCs and Dubai

But there’s also another rationale for flydubai – to keep rival LCCs out of Dubai. The success of Air Arabia has been a surprise to many executives at Emirates Group, as it has won significant amounts of passengers on the lucrative Middle East–India routes, although it was the launch of a base at Dubai airport by Jazeera Airways (only stopped when the Dubai emirate changed its fifth–freedom regulations) that was a real warning that the LCCs could not only prosper in the Gulf region in their own right and win point–to–point traffic but — much more importantly — could even take business away from the regional feed routes of Emirates Airline, due to significantly lower fares.

Emirates and the other large network carriers in the Gulf region (such as Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways) base their business models on (at least until recently) profitable long–haul routes eastwards and westwards, with substantial transfers between long–haul flights and short–haul flights at their respective hubs. But unlike in Europe, for example, many of the short–haul routes operated by Emirates and other Gulf carriers are claimed to be profitable in their own right, such is the regional demand, so the rise of LCCs poses significant challenges to these network carriers’ short- and mediumhaul operations. Indeed Emirates Airline itself has been expanding its regional services, and in the summer increased capacity on routes to Doha, Kuwait, Amman, Damascus and Sana’a in the Yemen through the introduction of larger A330 aircraft.

flydubai, therefore, can be seen as the lesser of two evils for the Dubai state: it’s preferable for the emirate to develop its own LCC at the state’s main airport (the world’s 5th busiest airport for international passengers, with 120 airlines operating routes to more than 200 destinations) than allow LCCs from neighbouring emirates to grab market shares. Under the same logic, although the enforced switch of flydubai’s base from the new Al Maktoum International airport at Jebel Ali to Dubai International (thanks to delays at Jebel Ali, which will now not open until the summer of 2010) may take away revenue from Emirates Airline’s short–haul flights, at least flydubai passengers can easily transfer onto long–haul Emirates flights there.

flydubai is also being used by the Dubai emirate to lead a counter–attack onto other emirates’ traffic flows, so as well as secondary destinations the airline is targeting primary destinations served by full service airlines. Indeed well before the Dubai–Doha route was launched in October Akbar Al Baker, the chief executive of Qatar Airways, warned Emirates that any LCC incursion into Qatar’s home market would provoke the launch of the airline’s own LCC in retaliation. At the Paris air show Al Baker said: “If Qatar Airways' market is eroded by a regional low–cost carrier, which seems to be the fashion, then Qatar Airways will join the fashion show.” Clearly rattled by the prospect of flydubai, Al Baker went on to say: “Do not intrude on our market with your crap airline, crap product and crap yields. Otherwise, we will immediately match them with a superior product but, of course, with a crap yield like them.”

Qatar Airways is clearly worried that flydubai will take significant number of passengers away from its Doha–Dubai route, particularly with flydubai’s fares between the two cities starting at AED200 (US$54). Currently flydubai operates 28 flights a week on the Dubai–Doha route, compared with 70 flights a week from Emirates and 100 from Qatar Airways.

Of course Al Ghaith says his airline is targeting a “different type of customer” to those of the network carriers, but it’s clear that some Qatar Airways’ passengers on the route will switch to flydubai — unless Qatar lowers its own fares significantly in response (one–way fares on Qatar were priced at QAR880/US$242 in early December). flydubai has certainly made its intentions clear – it held a launch sale in June and in September held a second sale, this time with fares on all routes discounted by 40% for a period of 10 days.

Qatar Airways claims it can launch a LCC within 90 days of making a positive decision to do so, and says it has put together a business plan for a carrier at Doha operating with A320s. However, even if it carries out this threat that’s an entirely reactive strategy, whereas the Dubai government has been proactive and has taken a long–term perspective on the strategic benefit of having its own LCC, even if flydubai will erode Emirates Airline’s revenues in the short–term.

Jazeera Airways

Kuwaiti LCC Jazeera Airways launched operations back in October 2005, with 30% of the airline owned by transport and media conglomerate The Boodai Group and 70% on free float following a successful IPO on the Kuwait stock exchange in June 2004. Since June 2009 its CEO has been Stefan Pichler, who was previously chief executive at Thomas Cook and chief commercial officer at Virgin Blue. (The airline is unrelated to the Al Jazeera TV network; Jazeera is the Arabic word for the Arabian peninsula.)

Jazeera Airways is unlike other LCCs in that it offers both economy and business classes. It currently has 610 employees and a fleet of 10 A320s, with 30 more on order that will start arriving in January 2010 and all be delivered by 2014. In February 2007 Jazeera sold and leased back its entire fleet (then consisting of eight A320s) to Sahaab Leasing, a joint venture set up between Jazeera, NBK Capital — part of the National Bank of Kuwait — and German investment company DVB, in a deal that Jazeera said enabled it to be “cash rich and free of debt”.

Jazeera currently operates to 27 destinations in 13 countries across the Middle East, India, North Africa and Turley and aims to serve more than 90 destinations by 2014. The airline is also adding extra frequencies on a number of existing routes in the winter timetable, including the key Dubai–Kuwait service, where it currently operates 45 flights a week.

However, Jazeera has faced a number of setbacks over the last six months. In the autumn it closed services from Dubai to Mumbai and New Delhi due to “overcapacity” on the routes, and now only serves India from Kuwait. But a bigger blow came in June when it had to abandon its multi–hub policy after the Dubai emirate changed its fifth–freedom regulations at Dubai International, its second base. Jazeera was forced to close its hub operation there, and it now operates what it calls a “virtual hub”.

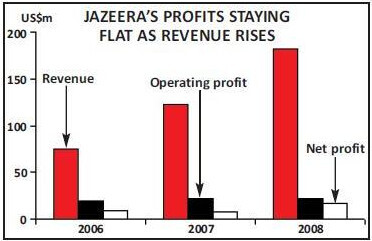

The restructuring of the network from a dual hub to a single hub operation hit profits hard. In 2008 Jazeera recorded revenue of U$182.1m, 48.4% up on 2007, and carried 1.4m passengers (compared with 1.2m in 2007), with operating profit of US$21.5m (4.1% down year–on–year) and a net profit of $16.6m, more than double the 2007 total.

However, for the January–September 2009 period Jazeera posted a 4.2% fall in revenue year–on–year to $125.2m. It recorded a $0.7m operating loss for the nine months (compared with a $17.9m operating profit in 1Q–3Q 2008) and a $5.1m net loss (compared with a $5.2m net profit in 1Q–3Q 2008).

The airline says it will post a profit for full 2009, but this is likely to be at the further expense of the classic LCC business model, as Pichler says that the airline will evolve into “a multi–market segment, multi–hub and a multi–class operator”. In October Jazeer relaunched its business class fare, which it says is now priced on average 35% lower than business class at rival airlines. The business product includes fully refundable and changeable tickets, dedicated check–in, access to business lounges, better seat pitch (33 inches), complimentary food, drink and in–flight entertainment, while aircraft have been reconfigured with an empty middle seat in order to offer more space to business class seats either side.

Jazeera is also committed to a multi–hub strategy, and Kuwait airport (where it is now the largest operator with an estimated 25% market share) will be joined by a second hub within the next six months — although this is likely to be outside the Gulf states and within the wider Middle East, where competition is not so strong, the airline says.

Pichler also says that his airline is looking for acquisitions, as “there will be some consolidation in the Middle East, particularly in LCCs”. Hopefully Pichler will stay around longer than predecessor Andrew Cowen, who became CEO of Jazeera in February 2009 (he was previously chief executive at Sama) before resigning just a few months later, in May, due to the “role not working out”.

Nas Air

Saudi Arabian LCC Nas Air is based at Riyadh airport and was launched as a domestic airline in February 2007 by the National Air Services Group and Abraaj Capital. The LCC is just one part of the NAS Group’s aviation interests, which also include an executive jet company and — until it went bankrupt in April 2009 — an A320 premium–class carrier called Kayala Airline. Kingdom Holdings Company, a holding company 94% owned by Prince Alwaleed of the Saudi royal family, bought a 30% stake in Nas Air in June 2008, increasing its stake soon after to 37% after buying the 7% stake held by Abraaj Capital.

Nas Air’s first international services were launched in July 2008 and today it operates to 13 domestic and 11 international destinations (all in the Middle East, the latest of which is between Jeddah and Sana’a in the Yemen, launched in September). Unlike Jazeera, Nas Air has no plans to expand into business class – with the potential exception of routes to Cairo; LCCs are not allowed to fly there, and so Nas Air is considering the addition of a business- class cabin to some of its aircraft in order to commence a route to that destination.

Nas Air has a fleet of seven A320 and four E–190s, with 20 A319s and nine E–190s on order, and is targeting a fleet of 14 A320s and 17 E–190s by 2012, and 27 A320s and 17 E- 190s by 2014. However, reports suggest Nas Air has been having trouble maintaining load factor as it has expanded through this year (it originally wanted to double passengers carried this year, compared with the 0.9m carried in 2008). In 2008 it had utilisation rates of less than seven hours per aircraft per day, and the airline has been trying to increase this to nine hours a day in 2009. However, an indication of problems it faces came when it leased out two Embraer 190s delivered to it this year to a Ukrainian airline.

In fact Nas Air has been unable to break into profit since its launch, thanks to its loss–making domestic operations which account for approximately two–thirds of all passengers carried. Originally these were all Public Service Obligation (PSO) routes that were transferred to it from Saudi Arabian Airlines as a precondition for government approval to start international services. These PSO routes consist of two types — trunk routes between Riyadh, Jeddah and Dammam (which are competed by the two Saudi LCCs and by Saudi Arabian Airlines), and other “thin” domestic routes that have to be operated under complicated routings determined by the regulator, GACA. No subsidies are paid to the airlines.

Although the Saudi government cut the PSO routes that NAS and fellow Saudi LCC Sama had to operate domestically from 20 to six each in July 2008, the key problem has been domestic fare caps. These were imposed by the government in 1998 in order to protect Saudi consumers and it was hoped that they would be removed before the launch of LCCs Nas Air and Sama in 2007. However this didn’t happen, and the fare caps have been “disastrous” according to one analyst, with NAS and Sama unable to raise fares when fuel prices increased in 2007 and 2008.

Nas Air (and Sama) have lobbied hard against the fare caps and eventually — in the summer of 2009 — the Saudi Arabian government gave Nas Air and Sama each a $53m interest–free loan (repayment details are unknown) in order to compensate it for losses incurred on the PSO routes. The fare caps have still not been lifted, although this is expected imminently.

Sama Airlines

Based at King Fahad international airport in Dammam, Sama Airlines was launched in March 2007 by Investment Enterprises, a local holding company, and a variety of private and institutional companies within Saudi Arabia.

Sama operates a fleet of six 737–300s and a single Jetstream 41 to eight domestic and seven international destinations (Amman, Aleppo, Alexandria, Assiut, Beirut, Damascus and Sharjah), as well as to a number of charter destinations.

Sama estimates that around two–thirds of its passengers are “new” travellers – i.e. people who have never previously flown with a network airline, with its core market being expatriates from the Indian sub–continent working in Saudi Arabia (there are 1.6m people of Indian descent living in Saudi Arabia) plus business executives and pilgrim traffic. Around 20% of all Sama passengers are pilgrims/religious travellers, many of them coming to the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca from various destinations throughout the UAE, Jordan, Afghanistan and Nigeria.

But while the Saudi Arabian government aims to double international visitors to the country by 2020 (to 8.8m visitors a year), Sama hasn’t launched a new international route (or indeed any route) since a service between Damman and Mumbai was started back in November 2008, as it has been trying to sort out its domestic flights and the problems of the PSO routes and the Saudi fare cap. Losses on the domestic routes forced the owners of the airline to invest another $50m in 2008, after the original $80m investment in working capital was spent in just a year.

CEO and founder Andrew Cowen left in December 2008 to join rival Jazeera Airways. Cowen had been unhappy about the domestic fare cap, which he said made domestic routes “chronically unprofitable”. He was replaced by Bruce Ashby, previously with US Airways and then chief executive of Indian LCC IndiGo Airlines.

The airline has 600 employees and is targeting 10m passengers carried in 2011, but this looks overly ambitious even though the airline says it will soon order another 20 aircraft for delivery over the next four years, with a decision on either A320s or 737–800s likely to be finalised by the end of 2009.