BA and Iberia: A merger of equals?

December 2009

After a decade of flirtation and 18 months of intense negotiation, British Airways and Iberia have finally set a tentative date for the consummation of their marriage. One of the more telling comments from Willie Walsh, BA’s CEO, during the conference call on the announcement was that BA “had been getting behind in the consolidation game ... and was no longer big”. Size, they say, isn’t everything, but for Iberia’s shareholders the decline in the value of Sterling along with the development of the worldwide financial crisis has emphasised the UK carrier’s shrinkage and seen BA’s market value fall by half relative to that of Iberia over the period of negotiations. At the same time BA can no longer claim to be the “world’s favourite airline”, thanks to Ryanair. However, as a result of the relative change in values it has probably been far easier to show this as a true “merger of equals” — BA’s shareholders now end up with 55% of the combined group, even though in operational and financial terms BA is more than twice the size of its Spanish bride.

A new holding company (to be registered in Madrid and under Spanish law) will be established – imaginatively for the moment called TopCo – into which will be injected the two flag carriers as separate entities. To obviate potential disputes over route rights, two separate national holding companies will be set up to own 50.1% of the voting rights (and none of the economic rights) of the respective carriers – and here BA and Iberia are following the “Air France/KLM model” developed in its pioneering cross–border merger of 2003.

The management of the new entity is being fairly spread between the two partners. Antonio Vazquez, Iberia’s recently appointed chairman and CEO, becomes group chairman, with BA’s chairman Broughton taking the subsidiary role as deputy chairman. Walsh steps up to be group CEO (incidentally elevating Keith Williams, BA’s finance director, to chief executive of British Airways itself) while Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, Iberia’s well respected CFO, becomes group CFO (although surprisingly he doesn’t seem to get a seat on the group board).

They are (deviously perhaps) planning to have TopCo’s main listing in London, with a secondary listing in Madrid and subject to the Spanish takeover code (and with all board and shareholder meetings to be held in Madrid). The group, however, will be managed from London. The two companies anticipate effecting the full merger by the end of 2010, allowing the usual lengthy period necessary for regulatory clearance and shareholder EGMs. As in the Air France/KLM merger the two are exchanging “assurances” for a five–year term (intriguingly enshrined in the voting structures of the subsidiary operating companies' boards of directors) as follows:

- Both airlines are to keep their main base in their home country with their own licences, certificates, codes and brands;

- Slots and destinations will be protected (for the benefit of the combined group);

- The network strategy will be developed in a way that reflects the importance of both the London and the Madrid hubs;

- There will be a balanced long–term development of the networks served from each of the Madrid and London hubs, and there will be a reasonable division of opportunities between the two networks;

- Labour relations will be handled locally;

- Neither Iberia nor the new holding company will provide any guarantee or use any cash or credit facilities to fund the BA pension schemes.

Importantly, not only are Iberia and “TopCo” relieved from any requirement to fund the black hole of BA’s pension fund deficit, but Iberia also has the right to terminate the agreement if it feels that the result of BA’s discussions with its pension fund trustees (due to be concluded by mid–2010) “materially impact the economic premises of the merger”.

Having been “left behind” in the consolidation stakes, Walsh insists that the structure put in place is truly “scalable”, and potentially it could be used as a vehicle to make more sense out of the oneworld alliance. There may be few sensible targets now left in Europe (oneworld partner Finnair would be a potential but intensely political possibility) but American may well be a candidate. The three (BA, Iberia and American) are still waiting for approval to set up their Atlantic joint venture (meant to have come through by October) – which would be part of the way towards a full merger under current rules, but which in any case nearly averts the need for any capital merger.

Meanwhile, the EU and US are meant to be negotiating Phase II of the Open Skies agreement in which it was originally planned to ensure open recourse to capital between the two blocs and get rid of the substantial ownership requirements. The original negotiations two years ago envisaged winding back all the concessions granted in Phase I (including open access to Heathrow) if the US didn’t agree to abandon the 25% foreign ownership limit on US airlines (whereas the US may have the threat of rescinding all the anti–trust immunities already granted). In the unlikely event that the discussions actually bear fruit, at least BA and Iberia will have the legal structure already established. However, American has its hands full at the moment – not only eagerly awaiting approval for its joint venture with BA and Iberia, but also anticipating a joint venture on the Pacific with oneworld partner JAL in the expectation of an open skies agreement between the US and Japan. Another suggestion could be bmi; while Lufthansa has yet to decide fully what to do with the airline (see Aviation Strategy, November 2009), Walsh has made it clear he would be interested in acquiring it.

The new entity

The marriage of British Airways and Iberia will finally create the third largest network airline group in Europe; a fleet of 400 aircraft, revenues of nearly €15bn (although still a long way behind Air France/KLM and Lufthansa) and a pro–forma market capitalisation of €4.3bn (nearly catching up with Ryanair’s current €4.5bn). As usual it is being promoted with the fallacy of being good for the consumer (surely the whole purpose of consolidation in a fragmented industry is to cut out competition?), although for BA’s and Iberia’s customer base there will no doubt be an improved market offer. BA’s prime strength is Heathrow – the North Atlantic gateway to Europe – and its position on routes to the US/Canada. Iberia’s strength is its very successful position on the South Atlantic (and the links with Spain’s former colonies). BA is severely constrained at Heathrow and its growth potential may be distinctly limited, while Madrid’s Barajas at least has space. Only 42 of BA’s 162 and Iberia’s 81 routes are currently shared destinations (and half of these are in Europe). The prime benefit surely comes to BA through the additional 11 unique destinations in South America it cannot currently serve.

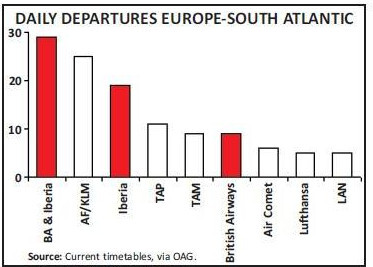

The combination of the two will certainly give the new group the strongest market position on the South Atlantic in terms of daily departures (see chart, above). And with regards to seats offered, BA and Iberia combined would have 30.5% of seats on routes to Central and South America – and when including oneworld partner LAN this gives them control over 34.4% of capacity (see table, below).

ATLANTIC CAPACITY, 2009

| Iberia | 25.9% |

| British Airways | 4.6% |

| LAN | 3.9% |

| oneworld total | 34.4% |

|---|---|

| AF/KLM & Alitalia | 25.0% |

| SkyTeam total | 25.0% |

| Lufthansa/Swiss | 7.8% |

| TAP | 12.1% |

| TAM | 6.9% |

| Star total | 26.8% |

| All others | 13.5% |

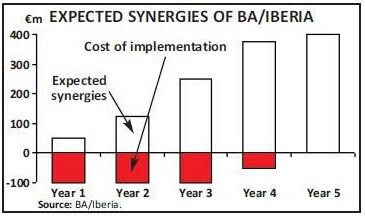

The two airlines have produced a rough estimate of future synergies: five years after implementation of the merger they anticipate improving results by some €400m annually – or a modest 3% of combined revenues (see chart). They gave few real details but suggested that a third of these synergies would come from revenue enhancements. This compares with Air France/KLM’s plans in 2004 to produce operational synergies of €700m within five years (although unlike BA–Iberia at the time it never indicated the cost of implementation), and AF/KLM recently stated that it had achieved annual synergies of €790m in its last financial year ending March 2009 – or 3.5% of combined revenues – and was now aiming for the magic €1bn by 2010/11.

The Air France/KLM benefits came quickly from running a dual hub system; co–ordinating schedules and services on join destinations; directing traffic flows respectively through Roissy CDG and Amsterdam Schiphol; joint pricing initiatives and combination routings to improve market offers. It was only in the past couple of years that they started concentrating on generating cost synergies – inter alia through IT and joint station management – and implementing an integrated joint revenue management. The big advantage to AF/KLM however was the positioning of their respective hubs – centrally located within the greatest mass of western European population and only 400km apart. On the basis that as network carriers they depended on feed coming from all directions, for those who have to transfer through a hub there would be very little difference in trip timings. The same appears true of the connections provided by Lufthansa and Swiss (and now Austrian) with Lufthansa’s four hubs of Frankfurt, Munich, Vienna and Zurich all in close geographical proximity.

On the face of it, it therefore appears that similar benefits may be far more difficult to achieve at BA/Iberia.

London Heathrow and Madrid Barajas are almost on the outskirts of the continent, and 1,300km apart. The most efficient traffic flows to the respective hubs for transfer traffic would come from places in between them rather than either side of them as in the case of the other two networks: and neither operates within Europe except to its own hubs.

There is a case for some improvement in joint revenues but almost solely perhaps by BA directing traffic flows from the UK through Madrid to South America, and maybe some benefit from Iberia directing traffic to North East Asia through Heathrow.

At the moment, for example, despite their long standing joint venture on UK–Spain routes, BA prefers to direct its traffic to some destinations it does not serve in South America through South American partners. For example it offers connections to Santiago de Chile (it no longer flies direct itself) by connection (onto TAM) through Sao Paolo – but with a long layover that gives a total trip time of 21 hours and makes its appearance in the booking systems look uncompetitive. BA does this of course because it gains the most economic benefit from this long–haul service. Under joint ownership the economic benefits will indeed be joint and with effectual network configurations will be in a position post merger to offer the most effective timings to the whole of Iberia’s 50 destinations in Latin America. In recognition of this, it appears that BA and Iberia are being rightly conservative in assuming less than a 1% synergistic benefit to revenues from traffic generation.

Both in the red

In the breakdown of sources of synergies, the two allocate a third of the benefit to the fleet and network (not necessarily the same as their statement that they expect a third to come from enhanced revenues). It looks as if they expect a quarter of the benefits to come from back office, admin and IT services; a good 15% to come from maintenance (and Iberia’s MRO business is a strong, profitable niche business with some unique attributes), with the rest from joint purchasing, ancillary businesses and sales and distribution (with some substantial potential benefits accruing from co–ordinating sales teams, particularly in the UK, Spain, North America and South America). They do, however, anticipate that it will cost them €350m over four years to achieve these results: not a bad payback if true. However, this merger agreement does not liberate either of them from the dire current environment. BA managed to produce operating losses of £111m for the six months to the end of September (down from a profit of £140m the year before) on revenues down by 14% (20% in constant currency terms). Traffic was flat, load factors up a little but unit revenues slumped by 12% while unit costs were up by 5%. Iberia announced operating losses for the nine months to the end of September of €246m (compared with profits of €73m in the same period last year) on revenues down by 20%. Traffic was down by 7%, capacity down by 6% while unit revenues fell by 14% and unit costs only by 6%. At least for both there are signs that the rate of decline in premium traffic and yields is dissipating on longhaul routes – and BA is starting to show real benefits from the move to T5 at Heathrow; but at the same time both airlines are suffering potentially damaging industrial unrest as they try to implement cost–saving measures. Both are heading for another year of heavy losses. although both appear to have the strength of liquidity to survive the current crisis.

What now? The two have signed the agreement but no benefits are likely to accrue (as long as the merger goes ahead that is) until well into the next upturn. They will have to circumvent the possible imposition of restrictions and to be competitive the two really need to get approval for the joint venture with American and counter the threats from the AF/KLM–Delta and Lufthansa/United joint ventures on the Atlantic.

BA desperately needs to sort out its horrendous pension fund problems and both need to ensure the right cost structure for the new environment. Presented as a “merger of equals”, it appears that while the BA professional airline managers will be at the helm, the purse may be held in Spanish hands.