Lessons in labour negotiation from Continental

December 2004

In late November Continental became the last of the top six US legacy carriers to seek wage concessions in the post–September 11 environment.

The airline announced that it would begin "accelerated discussions" with its work groups to achieve a $500m reduction in its annual payroll and benefit costs by the end of February. This would be in addition to the previously announced target of $1.1bn annual cost savings and revenue enhancements.

The move obviously reflects worsened industry fundamentals (oil and the domestic revenue environment), continued significant financial losses and fears of a liquidity crunch this winter. However, aside from that, it is probably the best piece of news that has emerged from the legacy carrier camp in recent memory.

This is because Continental is expected to succeed in its efforts (though some analysts doubt it will meet the February 28 target date).

Securing wage cuts is never easy, but the Houston–based carrier should be able to accomplish it without too much acrimony, perhaps even teaching the industry a few lessons about post–2001 labour negotiation.

It would certainly contrast with the latest developments at United and US Airways — both are now seeking approval in bankruptcy court to terminate labour contracts, while some of their unions are preparing for it by sending out strike ballots. This is the first time that substantive strike talk has surfaced since September 11.

Most significantly, however, wage cuts at Continental should put considerable pressure on American and Northwest — and probably make it easier for both — to secure the additional cost cuts that they need. Overall, the odds now seem higher that the currently solvent legacy carriers will attain competitive cost structures outside of Chapter 11.

In the first place, Continental is likely to succeed because of its amicable labour relations.

As testimony to that, in September the airline signed what it described as an "unprecedented partnership accord" with its ALPA–represented pilots.

The deal formalised a commitment to work together and seek common solutions through a difficult industry climate. It was a culmination of more than a year’s efforts to "develop a relationship based on providing each other with accurate, factual information and considering each other’s input regarding operational and other issues".

The process has already helped resolve some important issues, including the recent recall of 310 furloughed pilots "without imposing burdensome costs on the carrier".

Ironically, Continental is relatively healthy now only because it sought extensive help from Chapter 11 in the past. In chairman/CEO Gordon Bethune’s words, it was a "good example of a company that ripped its labour contracts and stiffed its creditors" in the mid- 1980s (under Frank Lorenzo’s rule) and while in Chapter 11 again in 1990–93. (Lorenzo’s labour moves were so abhorrent that they actually led to the revision of the Chapter 11 code, making it tougher for companies to terminate labour contracts in bankruptcy.)

Continental emerged from Chapter 11 in April 1993 with low unit costs but rock–bottom morale. However, Bethune, who is retiring at year–end, made improving employee relations and the corporate culture his priority throughout his ten–year tenure.The key part of the process was to gradually restore wages to industry standards (achieved by the turn of the decade), while maintaining the productivity advantages established in Chapter 11.

It was a feat to stay disciplined with the wage–restoration process in the late 1990s, when United allowed its labour costs to soar and other legacy carriers followed suit.

It has been suggested that Continental may be rushing the start of the wage concession talks so that popular CEO Bethune can play a role in the process before Larry Kellner takes over. One analyst argued that it might have been better for Kellner to spend his initial months "building new bridges with labour".

However, Kellner is a well–established member of the top management team and the bridges with labour may already be there.

If the management and the pilots (the key group) stick to the provisions of the September accord, and if Continental genuinely needs the wage concessions (meaning it can prove the need), the odds are for a successful outcome. The deal addressed labour unions' traditional grievances fairly comprehensively, emphasising trust, mutual respect, proper documentation and open and honest communication. It also formalised the pilots' requirement for a "fair share" of financial rewards when the airline returns to profitability. The union also agreed to "temper our communications".

When the deal was signed, ALPA’s president Duane Woerth suggested that it could be a model for the industry.

Explaining the key concepts at a recent conference, Bethune noted that "it is always difficult to ask people for money, but if you have it well documented, it means you're not guessing". He emphasised that it is important to do it only once, rather than keep going back to ask for more (like US Airways and United have done). Bethune also made the point that it takes years to build trust.

One particularly nice aspect of Continental’s move is that the top management will take the lead in pay reductions.

Kellner will take a 25% cut in salary and performance compensation, and four other top executives will take 20% cuts, effective from February 28.

The company expects about half of the $500m savings to come from productivity enhancements and benefit changes and the other half from wage rate cuts. The latter would be on a progressive scale, with lower–paid employees being asked for a lesser amount. There would be enhanced profit sharing and continuation of on–time performance and other incentive programmes.

Potential liquidity issues

Continental is in no immediate danger of bankruptcy. Its financial results have consistently been better than those of its legacy peers, as it has outperformed the industry on both the revenue and cost fronts.

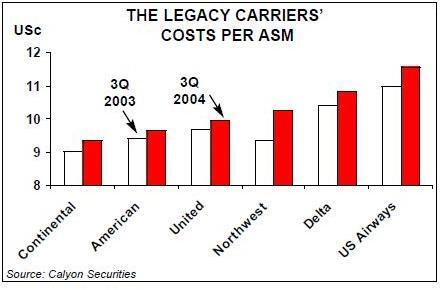

Its CASM, at 9.35 cents per ASM in the third quarter, is the lowest among the large network carriers. Remarkably, its quarterly cash position has remained virtually unchanged (in the $1.5- 1.6bn range) in recent years — a reflection of strong financial management. It still expects to end the year with $1.4–1.5bn of unrestricted cash — and it still holds a sizeable stake in regional carrier ExpressJet that could be monetised.

However, Continental is meeting its liquidity targets only because it missed a $245m pension payment in September, and because it is collecting $80m from the disposition of its Orbitz holdings in the current quarter. Missing the pension payment was totally legitimate — the company took advantage of the temporary relief provided by Congress in April, which allowed airlines to delay some of their near–term pension obligations. Continental still intends to keep its plan up to 90% funded on a current liability basis; instead of paying $245m in September and $40m in 2005, it will now pay around $300m in 2005.

Continental may not be able to maintain satisfactory liquidity through the weakest part of the winter in the current fuel and fare environment, and selling the ExpressJet stake is probably being kept as an emergency option or "plan B".

But even if liquidity does not become an issue this winter, Continental needs labour concessions to avoid losing its competitive advantage. It is clear that United’s and US Airways' cost cuts in Chapter 11, as well as the concessions American obtained on the courthouse steps in spring 2003, have narrowed the labour cost gap. In any case, all of Continental’s three major union contracts are now amendable, meaning that negotiations would take place anyway.

More clarity about wage benchmarks

Until recently, the big frustration for Continental was that it could see competitors gaining ground on the labour cost front but it did not know where the process would stop.

The goal posts have been shifting continuously since September 11. The airline was waiting for more clarity before responding, because it is determined to make wage concessions a one–time event.

The decision to seek $500m of labour concessions means that Continental feels that there is finally some level of clarity as to where the new wage benchmarks might be.

However, it was a little disconcerting to see Bethune also note in the press release that "competitive financial analysis would support our asking for substantially larger reductions" (though that remark was obviously meant for employees).

The following is a summary of the key labour developments at the other large legacy carriers:

United is the airline everyone, including Continental, is really watching. It was the one that raised the bar for the rest of the industry in 2000 — not just in terms of pilot pay but right across employee groups — and it now has to lower the bar. Having been in Chapter 11 since December 2002, United is trying to prepare for a successful (much delayed) exit from bankruptcy in 2005.

After already shaving $5bn from its annual expenses, the airline says that it needs $2bn more to secure exit–financing and long–term survival.

The $2bn cuts would come from additional labour concessions ($725m), termination of pension plans ($650m) and non–labour sources ($655m). Of the $725m labour total, pilots would contribute $191.2m, machinists $180m, flight attendants $137.6m and salaried workers and management $111.8m.

Consequently, United is in the middle of its second round of labour concession talks. Having already agreed to $2.56bn of givebacks, the unions have not responded well.

There was a watershed development on November 24, when United filed a Section 1113 motion, asking for permission to reject union contracts if consensual agreements on the $725m cuts have not been secured by mid–January. Significantly, the judge agreed to consider the motion, scheduling a hearing on it for January 10. United is also seeking a 4% company–wide pay reduction from January 1 until Chapter 11 exit.

The impression gained is that it was essentially the substantial size of United’s proposed cuts and the Section 1113 filing that clarified the situation enough and prompted Continental to act (to the extent that it is responding to competitors' moves).

As regards to pilot pay, competitors can now easily calculate the new benchmark.

United’s pilots first took a 30% pay cut; now they will see a further 18% reduction — either a straight pay cut or a combination of pay reduction and work rule changes.

US Airways has set important precedents in its two Chapter 11 filings that cannot be ignored by competitors. However, the implications are made much less significant by the fact that the company still faces high risk of liquidation this winter (and it is smaller than the other legacy carriers).

The airline entered Chapter 11 in mid- September — for the second time in two years — as most of its unions rejected a plan to cut labour costs by a further $950m, after $1bn of concessions agreed to in 2002. Only pilots and some small unions had agreed to additional concessions totalling $340m.

After imposing temporary 21% pay cuts, in mid- November US Airways filed motions to terminate three union contracts (covering ground workers, mechanics and flight attendants) and its remaining defined–benefit pension plans. Hearings on those motions began on December 2.

US Airways is in danger of not making it past January or February because of weak cash reserves and covenant and other issues with loans and financing agreements.

In addition, its flight attendants and ground workers have threatened to strike in the event that the collective bargaining agreements are abrogated — any strike would effectively be a death sentence.

However, if US Airways gets all the targeted cost savings and makes it through the winter, it could emerge from Chapter 11 with a cost structure similar to that of LCCs. It would have cut its labour costs by 60% from the 2000 level. American is expected to go into a second round of concessions talks to stay competitive, in response to United’s cuts and especially now that Continental has joined the fray. The airline has come a long way since April 2003, when it averted Chapter 11 by securing $1.8bn of annual wage and benefit concessions. Now one of the financially healthiest legacy carriers, American has noted on several occasions recently that the $4bn–plus annual cost savings achieved since September 11 are not enough.

Significantly, its pilots have also acknowledged that. Northwest has so far secured only $300m of its overall goal of $950m annual labour cost savings. The bulk of those came from a recent interim contract with pilots, which cuts pay by 15% annually over two years and leaves the pilots among the best paid in the industry. The annual saving is $265m, instead of the $440m asked for.

Northwest is in a relatively strong financial position, but it needs to reduce labour costs to remain competitive. It accepted an interim deal, first, because it had financial covenant issues — it was subsequently able to renegotiate a $975m credit agreement. Second, Northwest wanted the pilot deal as a "bridge strategy", to help get concessions from other groups, mainly mechanics and flight attendants.

The airline has told its pilots that it will have to ask for more concessions in the future.

Delta, which has been fighting to stay out of bankruptcy, recently secured a new pilot contract that will result in $1bn annual cost savings through wage cuts and benefit and work rule changes. Many of the key provisions took effect on December 1.

The deal was part of efforts to achieve $5bn in annual financial benefits from a multitude of sources, as compared to the 2002 level.

Some recent successes on the debt restructuring front have done much to avert the threat of Chapter 11 for the near term.

However, the pilot cost cuts are probably not enough to give Delta a competitive pilot cost structure (it does not have a cost problem with other work groups).

Even though some of the legacy carriers will inevitably find it tough to get their labour costs competitive, there is now a sense that the industry wage bar is falling faster than anticipated. One consequence noted by JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker:

"As wage rates fall, the economics of legacy airlines and LCCs continue to converge". Baker suggested that valuations would converge as well, meaning lower valuations for LCCs and higher valuations for the "rapidly rejuvenating" legacies.

The trend of the economics converging may be accentuated by changes in the age profiles of work forces. LCCs have lower labour costs for two main reasons: better work rules and younger workers on lower pay scales. While the work rule gap is obviously lessening, some of the cost differential is eroding as LCCs' employees age and the legacies reduce their work forces (particularly through early retirement and other voluntary programmes).

The other area where costs will be converging is pensions. There is now a consensus among legacy airline managements that the traditional defined–benefit plans will have to go. But there are no clear solutions on how pension reform could be implemented without disadvantaging employees or affecting the competitive positions of airlines. The industry is waiting to hear how the bankruptcy court will rule on UAL’s request to terminate its four pension plans. Also, Continental made the point that there should be congressional leadership on that issue in 2005.