Alaska: the smallest Major, the biggest turnaround

December 2003

Alaska Airlines, the smallest of the US major carriers, is emerging from the post–September 11 industry crisis in relatively good shape, with strong liquidity, a reasonably healthy balance sheet and profits on the horizon in 2004.

It will have to achieve further significant cost reductions in order to restore healthy annual profit margins, but the consensus opinion on Wall Street is that it will succeed in that task.

Alaska is also positioning itself nicely in the new industry environment as a high quality, leisure oriented point–to–point airline with unit costs "a notch above the low–cost carriers". Having already gained a foothold in some transcontinental markets to supplement its strong West Coast franchise, the airline has hinted at aggressive eastward expansion once the new cost targets are reached. It clearly has the potential to become an important player nationally.

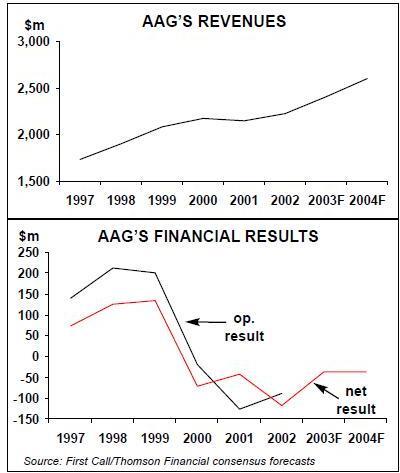

Why is Alaska apparently succeeding in making the difficult transition to a new industry environment? How could it possibly get the labour cost savings that it needs? Could other medium–sized niche–type operators — perhaps US Airways or European carriers — learn from its strategies? Other airlines can probably identify better with Alaska than, say, Southwest or JetBlue, because the Seattle–based company has struggled financially in recent years. Alaska Air Group (AAG, which also includes regional carrier Horizon Air) has lost money for four consecutive years (2000- 2003) — one year longer than the large US network carriers generally.

AAG plunged into losses early because it had another crisis to deal with before September 11 — the January 2000 crash of an Alaska MD–83.

The crash killed 88 people and resulted in a barrage of private lawsuits, a special safety audit by the FAA and a federal criminal investigation. (The airline was required to boost its maintenance staffing and safety and training practices, which contributed to a surge in unit costs, but all of it is now history since the criminal inquiry was closed last summer without the filing of charges.)

However, the financial losses themselves have not been that significant; for example, AAG’s 2002 net loss before special items accounted for only 3% of revenues. In fact, in the post–September 2001 period Alaska’s losses have been the lowest among the major carriers (except for Southwest, which has remained profitable).

AAG achieved an impressive 11.3% operating profit margin in the September quarter (virtually the same as Southwest's). However, the third quarter represents an unusually strong seasonal peak for the company because of summer vacation travel to the state of Alaska, and the latest profits were not enough to offset losses in weaker quarters. AAG is expected to report a (modest) $35–40m net loss before special items for full–year 2003.

Next year, however, should see AAG return to profitability. The nine analysts reporting on the company to First Call/Thompson Financial expect a profit before special items in the $25–50m range. The top estimate would represent a net margin of about 2%.

In a presentation at Citigroup Smith Barney’s annual transportation conference in mid- November, AAG’s chairman and CEO Bill Ayer provided some interesting insights into why Alaska has weathered the industry crisis so well and how it intends to move forward.

The key factors in the past two years have been, first, a quick traffic recovery, and second, revenues holding up better than competitors'.

Alaska has reported year–over–year traffic growth every month since January 2002. Its 2002 revenues ($2.22bn) were 2% above 2000’s, contrasting with the 15–20% industry average decline in the two–year period. Alaska’s traffic and revenues appear to have benefited from the resilience of the West Coast and Alaskan markets (the isolation factor) and the company’s focus on the leisure segment.

However, Ayer mentioned a third important factor: instead of parking aircraft and furloughing workers after September 11, Alaska redeployed its fleet in new markets.

In other words, the airline decided that operating its surplus aircraft, as long as at least variable costs could be covered, made more sense financially than parking them temporarily and having to also go through the upheaval and misery of furloughing employees. Of course, the added benefit was the ability to diversify the route network to include east–west operations.

This strategy illustrated Alaska’s Southweststyle caring and respectful attitude towards its employees — probably one of its greatest strengths. However, in contrast to the large network carriers, Alaska was in a strong enough financial position to experiment with new types of markets.

Alaska has been able to maintain unit revenues more or less unchanged in recent years by increasing its load factor, which is at the low end of the majors' range because of its point–to–point, primarily domestic operation. It has benefited from a yield management practice that, in Ayer’s claim, is the best in the industry in terms of technology, people and the way it focuses on markets and fare buckets. Of course, revenues have held up also because Alaska has maintained its traditional excellent service quality.

The company has a reputation for technological innovation and for being Internet–savvy. It was early to invest extensively in labour–saving technology and to provide electronic ticketing, and it claims to have been the first carrier to sell tickets on the Internet. In the September quarter, Alaska sold over 50% of its tickets directly to customers and issued 92% of its tickets electronically, while 45% of its customers checked in via the web or kiosk.

The only negative development, which contrasts with industry trends, is that Alaska’s unit costs have surged in recent years. According to Ayer, in 1999 Alaska’s ex–fuel CASM, at 7.49 cents, was close to the industry average — similar to Northwest’s and about a cent higher than Southwest’s. But by 2002 Alaska’s ex–fuel unit costs had risen to 8.52 cents, which was half a cent higher than Northwest’s and Continental’s.

Including fuel costs also (the conventional way of presenting CASM information), Alaska’s 2002 CASM was 9.85 cents. This looked alarming in light of the cost cuts implemented by American, United and US Airways this year.

Consequently, last June Alaska embarked on a new cost–cutting programme to reduce ex–fuel CASM to 7.25 cents by 2005. According to Ayer, the aim is to get back to the average in the ex–fuel CASM league, because that position produced strong profits in the past. "We really don’t have to have the lowest costs in order to have a very successful business model."

While the revenue outlook remains modestly positive, Alaska assumes flat revenues for the purposes of its financial recovery plan. This implies, first, that the focus is totally on the cost side to get the profit margin back. Second, there could be upside to the financial projections.

"Alaska 2010" plan

The 7.25–cent ex–fuel CASM target for 2005 is actually part of a broader seven–year vision to transform Alaska into a profitable, larger airline with a greatly expanded network. Entitled "Alaska 2010" (a reference to year 2010), the plan includes employee and customer elements in addition to the usual growth and financial targets.

- Employee elements The plan aims to provide "excellent job and retirement security" and make Alaska "one of the best places to work in America".

- Service and brand The aim is to provide "the best value" (a combination of product and price, not necessarily the lowest price) and have "one of the most respected brands in the USA". Since Alaska already has a strong brand, it will simply strive to continue building on it.

Ayer described the brand as having four pillars: "user–friendly" (as opposed to complicated), "engaging experience" (as opposed to routine),"purposeful innovation" (as opposed to $1) and "Alaska spirit" (as opposed to impersonal). The key goal is to "maintain differentiation".

All of this basically means that Alaska will think twice before doing anything to reduce its on–board service.

For example, it feels that the "buy–on board" (food) programmes introduced by competitors would be detrimental to its brand. Nevertheless, short haul routes may see some changes as the airline continues to "refine our understanding of customer value".

- Financial targets The plan is to achieve an annual pre–tax profit margin of 10%. Alaska believes that profitability at that level would "weatherproof" it to any economic downturn, enabling it to avoid dramatic capacity shifts.

- Growth targets Achieving the profit margin targets would permit annual capacity growth in the 8- 10% range. In the plan, Alaska envisages having a fleet of 150–175 aircraft by 2010, up from 109 at the end of this year.

Ambitious cost cutting programme

The cost cutting programme aims to eliminate $307m from Alaska’s 2001 ex–fuel operating cost structure by 2005 — a relatively ambitious 20% reduction. In ex–fuel unit cost terms, this would represent a reduction from 8.73 to 7.25 cents in the three–year period. (These targets are for Alaska Airlines only; Horizon, which accounts for about 19% of group revenues, has a regional carrier–type higher cost structure.)

The programme is apparently running on target, with ex–fuel CASM of 8.52 cents achieved in 2002 and 8.35 cents expected in 2003. Nevertheless, getting from 8.35 to 7.25 in just over a year will be a formidable undertaking.

There are three components. First, the airline targets $120m annual savings from a variety of strategic initiatives. Efforts under way include boosting sales through Alaska’s own web site from the current 29% to 50%, improving heavy maintenance efficiencies, lowering insurance costs and harmonising Alaska’s and Horizon’s flying (meaning more aircraft transfers between the two to better tailor capacity to demand on individual routes).

About $80m of these savings are already included in the 2003 results, leaving $40m to be achieved in 2004.

The second component is a $112m hoped–for employee contribution to "bring labour costs in line with market and make some changes to employee benefit programmes". There is no specific timeframe. While it is too early to predict the outcome, an early positive sign is that the employee groups have agreed to begin a dialogue. The pilots, whose contract talks began last month, have reportedly been asked to take a 23% pay cut.

The $112m request from labour amounts to about half a cent in CASM. In other words, it would make quite a big difference in Alaska’s cost structure, but not getting it — or most likely, not getting all of it — would not be a serious problem.

On the positive side, Alaska has a history of great employee relations and appears to know how to deal with labour issues. However, it is always a tough challenge to persuade workers to make cuts when the company is in a relatively strong financial position.

The remaining $75m annual savings would come from yet–to–be–determined product changes and cost initiatives. The intention is to finalise and implement those measures in 2004.

In a recent conference call, Alaska’s top executives stressed that at this point the 7.25 figure was not offered as "guidance". Next year’s goal excluding labour would be 8 cents, and labour could bring it to 7.5 cents, leaving 0.25 cents to be squeezed out in 2005.

While it is generally nice to see precise figures (as opposed to just vague talk about cost cutting), it is a little surprising that Alaska would want to publicly commit itself to a specific CASM goal. Other US carriers have avoided that, in part because they view CASM goals as a moving target but also because they remember Delta’s disastrous "Leadership 7.5" programme.

But Alaska likes to do things differently and has an excellent track record in cost cutting. In the mid- 1990s, when it got caught in fierce market share battles between Southwest and United’s Shuttle, it staged a rapid and extremely successful cost cutting programme, reducing CASM drastically while maintaining excellent service quality.

Transcontinental expansion

Alaska has used the industry downturn to expand and diversify its route network. In 2000 it had an all–West Coast, north–south operation spanning from Alaska to Mexico. Now it also has several East Coast spokes, operated non–stop out of Seattle. In the third quarter, the transcontinental and Denver markets accounted for 12.1% of its total ASMs, up from 5.7% a year earlier.

Going transcontinental was possible because of Alaska’s new longer–range Boeing 737s. The airline is pleased with the economics of the routes today. Some of the markets, such as Atlanta and Florida, have responded well to the 737–900s, which provide more favourable economics than the 737–700s.

The transcontinental markets are still under development and have very low frequencies, typically only one or two per day. But despite that, they have already attracted significant flow traffic from Alaska and Western Canada, which has helped make them Alaska’s best–performing segment in terms of average load factor (80.1% in the third quarter, 7.6 points higher than system average).

Alaska believes that the new routes to the East Coast, as well as its airline partnerships, played an important role in securing a new corporate account with Microsoft — a major coup announced on October 1. Microsoft apparently switched accounts away from other airlines to make Alaska its preferred partner.

The new services also help save money on the FFP front. Previously Alaska’s frequent–flyers, having earned their miles along the West Coast, typically claimed the miles on other airlines' coast–to coast services, and Alaska had to pay its competitors.

One of Alaska’s aims now is to better penetrate the East Coast point of sale. It would like to secure corporate accounts in the East — something that could allow transcontinental frequencies to be increased more quickly.

After 2002’s 8% capacity growth, Alaska managed another 7.3% ASM increase this year. Next year’s plans currently envisage 5% ASM growth — the result of a net addition of seven aircraft in 2003 and a modest increase in utilisation. Alaska executives have hinted at the possibility of a couple of new cities in the East in 2004 or early 2005. But otherwise the message coming across loud and clear (undoubtedly aimed at the workers) is that while there are numerous good potential growth opportunities — in the eastern half of the country, as well as Hawaii, Caribbean and Mexico — the cost reductions will have to come first.

As Ayer expressed it: "Low costs equal low fares and lots of possibilities".

It is easy to picture Alaska eventually carving itself a successful niche in transcontinental markets and becoming a strong competitor nationally.

After all, it has retained substantial market shares on many of its West Coast routes despite significant competition from Southwest and United.

In the meantime, Alaska will continue to rely on its alliances with American, Continental, Northwest and others to connect across the country. The airline feels that, because of its geographical disadvantage and limited network, it benefits disproportionately from such partnerships.

As the latest alliance development, Horizon has partnered with Denver–based Frontier Airlines to operate up to nine 70–seat CRJ–700s as "Frontier JetExpress" under a 12–year agreement starting in January. Here AAG is trading off some reduced flexibility in the short term (fewer RJs available to help Alaska) for long–term broadening of opportunity. It is worth noting that Horizon differs from the typical US regional carrier model; like Alaska, it is essentially a point–to–point carrier and has only a 35% connecting traffic component. After a year of significant fleet activity at Alaska (11 new 737–700/900 deliveries and four MD–80 retirements), there now appears to be a natural pause.

The 2004 fleet plan is very simple: receive one 737–900 and return to lessor one MD–80. Depending on the outcome of some lease negotiations, the airline may also end up returning additional 737–400s.

Horizon, in turn, is taking a year’s break from RJ deliveries. Under a recent restructuring of its remaining Bombardier firm orders, it converted two CRJ–700s due in 2004 to two 70–seat Q400 turboprops — the only aircraft it is now taking next year.

The other 10 CRJ–700s on firm order will be delivered at a rate of two per year between 2005 and 2009.

Some of this seems rather prudent in light of AAG’s relatively healthy balance sheet. The company had an ample $749m of cash at the end of September. Its lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio of 78% was the third best in the industry (after Southwest’s 38% and JetBlue’s 71%), well below the 95%-plus now recorded by the other major carriers,.