America West: fate in the hands of the Stabilization Board

December 2001

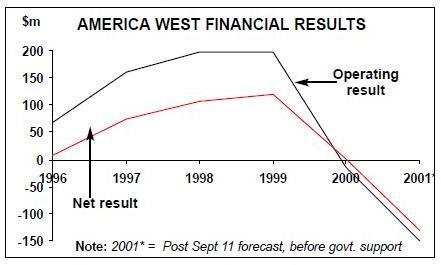

Of the US major airlines, America West is the one most at risk of not making it through the winter. The Phoenix–based carrier entered the current industry crisis with extremely poor liquidity — just $80m in cash at hand and no available credit facilities on September 10 — after two years of deteriorating earnings and weakening financial profile.

Without the $15bn federal emergency relief package, which included $2.5bn of immediate cash payments to US airlines, AWA would have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the last week of September.

In addition to the $60.3m received as the first instalment of the government cash grant, America West managed to raise $70m in mid–October through the sale–leaseback of eight A319s and some flight simulators and spare engines. This was a feat considering that the airline had little in terms of unencumbered assets (it converted secured aircraft debt financing to leveraged leases with the help of a New York bank).

AWA expects to collect the remaining $60m cash grants over the next couple of months — probably $48m by year–end and $18m in early 2002. As a result, and assuming cash burn of $1–2m per day in the current quarter (the actual rate in mid–November), the company could end the year with cash and short–term investments only slightly below the $144.5m reported for September 30.

However, those reserves will not be sufficient to take AWA through the winter, let alone through a post–attack demand slump and economic downturn that could continue until late 2002. The airline needs substantial additional liquidity probably by the early part of next year, as well as significant further cost reductions, to survive the downturn.

The company is clearly unable to raise funds through normal commercial channels. Its corporate credit ratings are in the "vulnerability to default" grades. Standard & Poor’s recently cited its "minimal financial flexibility" and the possibility of a bankruptcy filing as reasons for yet–another downgrade.

Consequently, America West is now the first airline seeking to take advantage of the $10bn federal government loan guarantee programme.

It applied in mid–November for $400m in federal loan guarantees which, in turn, would be a catalyst for $600m of financial support and concessions negotiated with key business partners and constituents — banks, creditors, manufacturers, lessors, vendors, state and local governments, shareholders and employees. All of that support is contingent on the approval of the loan guarantee application.

America West’s fate will therefore be determined by the four–member Air Transportation Stabilization Board, consisting of the transportation secretary, treasury secretary, Federal Reserve Board chairman and comptroller general. The board has auditing powers and broad discretion to approve or turn down applications.

When processing applications, the government officials will face the tough task of sorting through many conflicting objectives and guidelines. On the one hand, an airline must show that it is in serious enough trouble to be denied access to alternative financing. But the guidelines also require preference to be given to strong applicants that can demonstrate their ability to repay the loans.

It is hard to predict at this stage what AWA’s chances are, but UBS Warburg analyst Sam Buttrick suggested recently that the government may opt to apply the loan guarantees liberally. Others have mentioned the support promised by state and local governments, which will make it hard to deny applications. However, every application must include a solid business plan that demonstrates reasonable long–term survival prospects and ability to repay the loan.

The loan guarantee application

America West is asking the government to guarantee a $400m tranche of a $426mloan, thus meeting the requirement that the guarantee should cover "less than 100%" of the loan. Citibank has agreed to underwrite the $26m at–risk portion. Even better, there is a commitment to provide $135m of additional aircraft financing.

The government–guaranteed loan would be for a seven–year period — the maximum permitted by the guidelines. Ability to borrow over a longer term was an important victory for AWA when the guidelines were formulated, because the stronger carriers had pressed for maximum terms as short as 12- 18 months. "As economy rebounds, the loan would be repaid ratably from 2005 to 2008 while the company retains comfortable cash balances", AWA said in a statement.

AWA is understandably determined to avoid having to give the government stock or options as collateral — a controversial last minute addition to the guidelines patterned after the 1980 Chrysler buyout. Instead, the airline is proposing to compensate the government and taxpayers for risk through a "guarantee fee structure that increases as the airline becomes more profitable".

The guidelines require applicants to be carriers that suffered as a result of the September 11 events and for whom "credit is not otherwise reasonably available". The wording of the regulations is not very clear on that point, but the government is determined not to compensate the industry for the effects of a weak economy or keep airlines afloat if they were failing anyway.

Some industry insiders earlier questioned whether AWA would qualify in that respect, because it had severe liquidity problems before September 11. It had been unable to obtain any line of credit since June, when its existing $125m facility was reduced and frozen at $90m due to financial covenant violations.

However, AWA recently disclosed that just before September 11 it arranged a new liquidity facility that was "sufficient to weather the most severe of projected economic downturns". The facility was not yet in place on September 11, so the parties involved (believed to be Airbus and GE Capital) were able to terminate the commitment after the attacks.

CEO W. Douglas Parker explained at the recent Salomon Smith Barney transportation conference that the company had signed term sheets in respect of aircraft orders that included a separate $200m loan. The transaction had been expected to close in early October and it would have brought liquidity to $250–300m. That documentation could significantly help the loan guarantee application.

Concessions

Securing the loan guarantees would facilitate an impressive $440m worth of concessions, probably amply satisfying the recommendation that applicants obtain assistance from "key constituents" in order to restructure costs. The details are not yet publicly available, but here is Aviation Strategy’s assessment of what the package is likely to contain.

First, AWA is known to have secured concessions from its aircraft lessors. In October, in an effort to conserve cash and speed up the negotiations, the airline suspended some lease payments, as a result of which it was served default notices. The talks focused on rent reductions, restructuring of costs and obligations and the potential early return of some aircraft.

Lessor concessions are particularly important because AWA has a substantial $2.2bn of operating lease commitments (compared to $352m of long–term debt at the end of September). Consequently, the end result should be a de–leveraging of the company.

Even before the lessor concessions, AWA has considerable flexibility to reduce its fleet because a relatively large number of aircraft are on short–term leases. As many as 15 leases — three A320s and 12 737–300s — expire over the next year or so.

AWA has undoubtedly negotiated an agreement to defer aircraft deliveries. The company said earlier that it was hoping to defer the deliveries of seven A319/A320s scheduled over the next 12 months.

AWA may also have secured financing from Airbus (and GE Capital) for future aircraft covered by the purchase contract. At the end of September, the carrier had 28 A320–family aircraft on firm order for delivery by the end of 2004. Of the $1.1bn of firm order commitments, $195.2m of financing is in place covering deliveries through November 2002 under the original schedule.

AWA may also have secured concessions from its credit facility lenders. In October it was in discussions that sought to waive collateral shortfalls resulting from declining aircraft values, extend repayment terms (the facility was due to mature at the end of 2002), reduce interest rates and eliminate certain financial covenants.

The company was in negotiations with virtually all of its vendors about reducing costs and improving operating flexibility. Some of those payments were suspended after September 11 to save about $40m in cash by the end of that month.

It is not known whether the package includes concessions from regional airline partners. AWA has been in negotiations with at least Mesa, with which it has an excellent relationship, about restructuring existing cost reimbursement and revenue sharing arrangements.

The indications are that employees have not been asked for concessions at this stage. At the company’s third–quarter earnings conference call, Parker pointed out that the 2,000 layoffs implemented in October (about 14% of the workforce) already significantly reduced the quality of work life for the remaining people and that AWA’s wages are not above market rates. However, while no further layoffs were anticipated, the possibility of concessions had not been excluded. The company is in contract negotiations with its ALPA–represented pilots.

Ability to repay the loan?

The loan guarantee application included a "detailed and well–documented" seven year business plan that demonstrates ability to repay the loan over time. While no financial projections have been released, America West executives say that the plan is based on conservative economic rebound assumptions and revenue forecasts that are below Wall Street consensus estimates.

The airline is selling itself as a success story of deregulation, being the only post- 1978 entrant (1983) that has made it to "major carrier" status. AWA argues that, with its low cost structure and a large hub and spoke network centred on Phoenix, it keeps in place price discipline across the rest of the airline industry.

In particular, AWA argues that it has significant impact in transcontinental markets, where its 7–day or closer–booked fares are about 40% below competitors' lowest fares. Even though its overall domestic market share is only 3%, it is the third largest carrier (behind United and American) in the large Northeast–to–West Coast market.

The airline points out that it is much larger in size than low–cost carriers like Frontier and ATA and that Southwest has a different product and focuses on different markets. Of the 86 markets served by America West, 51 are not served by Southwest.

Parker explained at the Salomon Smith Barney conference that yields at Phoenix are about 85% of what other airlines are able to generate at hubs such as Chicago, Atlanta and Dallas Fort Worth.

Consequently, AWA’s cost structure has historically been 15–20% lower than that of other hub and spoke airlines. It has been able to maintain the cost differential, primarily through lower labour costs.

While AWA was profitable through the best part of the 1990s, its profit margins remained low because of persistent operational problems, which the company now blames on unmanageably rapid growth. 2000 was a particularly tough year operationally, which meant that AWA’s financial profile began deteriorating long before economic slowdown hit the airline industry generally.

However, AWA has staged an impressive operational turnaround since taking various corrective actions in July 2000. The company also claims that it has been outperforming the industry this year — and particularly since September 11 — in terms of load factors, unit revenues and EBITDA margins. This is in part because traffic has held up better on the West Coast and because leisure demand has been less affected than business travel — factors that have also helped Alaska Airlines.

Parker said that AWA’s average load factor had recovered to 71% by the last week of October, which was a higher than a year ago (on reduced capacity). While industry traffic was down by 60% on September 19, AWA’s traffic was down by 42%, and at the end of October those percentage declines were 23% and 10% respectively.

While yields in late October were still 20% below year–earlier levels, AWA blamed it on fare sales led by other carriers. After outperforming the industry in RASM in the past eight months, AWA now believes that it can continue to close the revenue gap as industry unit revenues recover gradually. Unit costs are expected to remain flat in the current quarter, despite a 15% capacity reduction and unfavourable fuel hedges.

AWA reported a $31.7m net loss for the third quarter, including the $60m cash grant, compared to a marginal profit of $1.3m a year earlier. Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg pointed out that the pretax margin (22.4% negative) was the worst among all the major carriers. Net loss for the first nine months of 2001 was $87m on revenues of $1.7bn. However, Parker said that AWA’s 15.6% EBITDA margin in January- September was the industry’s third highest (after Southwest and Continental).

The airline implemented the 20% post attack schedule cut entirely through frequency reductions, spread fairly evenly across its three hubs. It wanted to maintain a presence in all markets, because its main competitor is Southwest. Parker said that he expected about half of that capacity to be restored over the next 12 months, depending on demand recovery, which would result in a small year–over–year ASM decline in 2002.

Parker’s industry revenue predictions are less optimistic than those of other airline CEOs. In early November he suggested that a full recovery could take 12–18 months. Key determinants are the economy and "perceived hassle factor", which is affecting business travel demand much more than fear of terrorism.

AWA is also telling the government that it is well positioned to grow when economic recovery gets under way, because Las Vegas and Phoenix are the nation’s two fastest–growing cities. By most analysts' estimates, the Phoenix hub remains undersized. AWA’s plan is to grow it to over 300 daily departures, from the 250 pre–attack level.

Parker also points out that, contrary to analysts' dire predictions in the mid–1990s, AWA has been able to expand its market share at Phoenix despite Southwest’s major presence. Since 1995, AWA’s market share there has grown from 38% to 46%, while Southwest’s has declined from 34% and 28%. Southwest does not appear to have plans to grow substantially at Phoenix.

While America West is now naturally being talked about as one of the most likely acquisition targets if there is industry consolidation, at this point the management’s total focus is on securing long–term viability for independent operation.

In a recent research note, Linenberg detected "promising signs that the carrier will indeed survive the industry crisis and come out of it stronger than before", as long as the short–term liquidity issues are resolved. He also felt that the operating performance improvements "hint at a stronger structure that will be more efficient and profitable when traffic picks up again".

| In operation | On order | Comments | |

| 737-200 | 14 | ||

| 737-300 | 44 | ||

| 757-200 | 13 | ||

| A318 | 15 | Del. 2003-05 | |

| A319 | 30 | 3 | Del. 2002 |

| A320 | 45 | 10 | Del. 2002-04 |

| Total | 146 | 28 |